Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi: The Last Master

As the 19th century drew to a close, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi gave classic Japanese woodblock printmaking a sunset burst of glory.

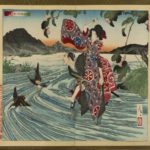

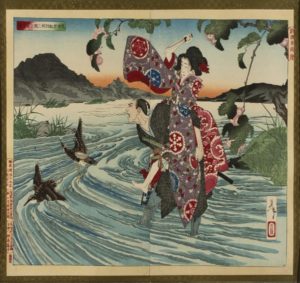

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, The Demon Omatsu Murders Shirosaburõ in the Ford, 1885, color woodcut on two panels (diptych), 13.125 x 17.6875 in.

- Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, A Noh Actor as the Warrior Kamasaka Chõhan on a Night with a Misty Moon, 1886, color woodcut, 15.5 x 10.5 in.

- Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, The Demon Omatsu Murders Shirosaburõ in the Ford, 1885, color woodcut on two panels (diptych), 13.125 x 17.6875 in.

- Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, The Heian Poet Yasumasa Playing the Flute by Moonlight, Subduing the Bandit Yasusuke with His Music, 1883, color woodcut on three panels (triptych), 14.0625 x 28.875 in.

- Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, Fujiawara no Ariko Weeping Over Her Lute, 1886, color woodcut, 15.5 x 10.5 in

The life of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–92), the last great master of the Japanese ukiyo-e tradition, was almost as lurid and macabre as the images the artist created. Struggles with depression and poverty, as well as multiple ill-fated love affairs, haunted his career like one of the terrible creatures from his famous series, “New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts “(1889–92). The tragic figure cut by Yoshitoshi, that of the tormented romantic, has its own particular resonance with a shadow world of art and artists in Japan. The lives of 20th-century counterculture writers Osamu Dazai and Yukio Mishima, whose lives ended in suicides slow and fast, respectively, and avant garde saxophonist Kaoru Abe, who died at 29 leaving behind only a library of live recordings, seemed to follow a similar downward trajectory, in which a string of endless calamities was colored by violent explosions of creative brilliance.

Decades earlier, through this same stubborn mix of passion and madness, Yoshitoshi and ukiyo-e persevered as the Edo period gave way to the Meiji and the world and the nature of images changed rapidly. Cheaper and easier printmaking methods imported from the West, along with the new medium of photography, killed the market for classic color woodblock prints. Indeed, the seething, nearly pornographic violence of some of Yoshitoshi’s most infamous works, which include gleefully graphic murders, horrific battle scenes, and worse, have been attributed to Japan’s violent collision with technology and modernity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In Yoshitoshi’s work, personal angst and the fury of the past lash out at the present with linework so razor-sharp it draws blood. Implicit (and explicit) in Yoshitoshi’s work is a characteristically Japanese refusal to submit—to meet imminent defeat with violence, which the final master of the disappearing art form poignantly dramatized through images of honorable suicides and samurai fighting to their last breath. His subject matter of demons, gore, and crime may ultimately distract from the true violence at the heart of Yoshitoshi’s work, a violence more Hegelian than Grand Guignol—that of the past in mortal combat with the present.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s exhibition “Yoshitoshi: Spirit and Spectacle,” which opens on April 16 and runs through August 18, steers clear of the standard emphasis on the artist’s personal struggles, instead choosing to focus on his place in a rapidly changing world and the myriad of external factors that helped shape his output. The master’s paintings and woodblock prints are presented in the context of the markets, publisher’s requests that guided them, and technical innovation–a relatively novel phenomenological approach in assessing an artist whose character seems to loom so large. If this new methodology weren’t enough, the show also calls into question the pervasive characterization of Yoshitoshi’s work as overwhelmingly

gruesome and tawdry. Pulling from the museum’s own collection of nearly 1,200 prints by the artist (the largest collection outside Japan), less-known aspects of Yoshitoshi’s work are emphasized through a carefully chosen selection of over 70 images. Rare early works, including triptychs depicting a fireman’s parade (1858) and a devastating fire (1878), help to illustrate the evolution of Yoshitoshi’s career and practice in full, presenting him as both radical innovator and disciple of tradition.

Yoshitoshi brought his unique stylistic expressiveness to a wide range of historical and contemporary subjects, and within many images we find the tension between the old and the new. A three-panel color woodblock print from 1881, The Giant Twelfth-Century Warrior-Priest Benkei Attacking Young Yoshitsune for His Sword on the Gojo Bridge, is an excellent example of a common ukiyo-e subject given explosive new life by Yoshitoshi. Benkei was a nearly unbeatable warrior monk of Japanese folklore who was said to be part demon. In Benkei’s most famous exploit, he roamed the streets of Kyoto intent on accumulating 1,000 swords by defeating their owners. After collecting 999, Benkei encountered the famous young samurai Minamoto no Yoshitune. The two heroes dueled at Gojo bridge, and Benkei was finally defeated, thereafter becoming Yoshitune’s retainer.

Yoshitoshi’s depiction of the battle is a marvel of composition that seems to prefigure the widescreen samurai epics that would fill the screens of Japanese cinemas throughout the 1950s and ’60s. The compactness and acrobatic intensity of the figures, as well as their radically divergent spatial coordinates, also demonstrate Yoshitoshi’s great influence on manga, particularly on Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima’s wildly popular Lone Wolf and Cub series. Yoshitoshi’w prints foreshadow that series’ iconic interpolation of action into moments of intense stillness. The hulking figure of Benkai is crouched on the far left of the triptych, and far to the right Yoshitune is airborne. The placement of the figures bisects the work diagonally, creating a unique visual excitement. At the center of the work, though, is the moon, large and full, evoking stillness in the heat of battle. Placed at the center of the composition, it freezes the action, giving the moment of combat a philosophical resonance. The profession of samurai was accompanied by a strict code of conduct which incorporated aspects of Zen Buddhism, Neo-Confucianism, and Shinto. So although this is a scene of action, Yoshitoshi draws our attention to the fact that it is not a mere fight but rather a moment of actualization for the warriors, in which skill, mind, and spirit coalesce into a singular manifestation of bushido, the way of the warrior.

The exhibition’s high point is the 1883 color on panel triptych The Heian Poet Yasumasa Playing the Flute by Moonlight, Subduing the Bandit Yasusuke with His Music. In this composition, widely considered to be Yoshitoshi’s masterpiece, the dynamic between action and stillness moves beyond the juxtaposition of foreground and background and into the picture’s narrative. The scene depicts the famous musician Fujiwara no Yasumasa in a field at night, eyes closed, playing his flute. Crouched in the grass to his left is his estranged brother, Kidomaru, who, initially intent on stealing Yasumasa’s golden robe, has become mesmerized by the sounds of the instrument. The squatting figure of Kidomaru is filled with a muted potentiality, while Yasumasa, standing erect against a powerful wind, is the picture of serenity. In the triptych’s left panel the moon, one again large and full, looks down on the scene—the third member of an ethereal nocturnal trio.

The composition is bold, and Yoshitoshi takes care to create an exciting path for the eye beginning at the moon, down the figure of Yasumasa, and once again upward toward Kidomaru, whose leg enters the center panel just enough to link all the elements. Yoshitoshi’s rendering of this scene—popularized in kabuki theater and earlier ukiyo-e interpretations, including one by his mentor, the ukiyo-e master Utagawa Kuniyoshi—is detailed, with the windblown grass receiving the same attention as the human figures. The exaggerated bodily proportions and facial gestures of earlier renderings are gone, replaced by a density of figure and a more naturalistic perspective. With Yasumasa Playing the Flute, Yoshitoshi creates harmony between stylization and relatively realistic representation. The scene moves beyond kabuki, giving this particular piece of folklore new life and bringing the past into the present, albeit with a ghostly touch.

Beyond Yoshitoshi’s achievements in composition and realism, his pioneering tendencies extended into his choice of materials, as well. Aniline inks commonly used in flexographic printing entered Japan from the West, allowing Yoshitoshi to fill his images with brilliant colors. In the color woodcut The Filial Daughter Chikako and the Moon after a Snowfall at the Asano River, from “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon” (1885), Yoshitoshi uses vibrant color to place the flowing garments of Chikako in stark contrast with the muted blues, whites, and grays of the landscape. Chikako’s body is rendered with Yoshitoshi’s characteristic compact physicality—her legs raised as she dives into the icy waters below. The composition, now vertical, maintains the artist’s three-figure triangulation, with Chikako, two cranes, and the moon inviting the eye to move in a seemingly endless trip from one element to the next and back again. Again, action is frozen in time, Chikako’s presumably fatal fall suspended for eternity. The masterfully rendered image transforms myth into moment and tragedy into beauty. Try as he might, though, Yoshitoshi could not stop the clock from striking midnight on ukiyo-e.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s exhibition allows visitors to witness a major turning point in the history of image making. Yoshitoshi’s doomed project of permanently resuscitating ukiyo-e may have failed, but the impact of his work continues to this day. With Japanese animation, or anime, gaining widestream appeal, the influence of Yoshitoshi can be seen in any number of the hyper-stylized TV shows and movies, where time appears to stop as contorted, expressive figures move through space. Ultimately, Yoshitoshi’s fight with the new Japan, radically altered by its fateful opening up to the West, was not fought in vain. The artist’s enduring influence proves that the future of Japanese popular images, and indeed of global animation and comic aesthetics, belonged to him.

—

By Chris Shields