Utagawa Kunisada: 10 Must-See Masterpieces

by Will Heath | ART

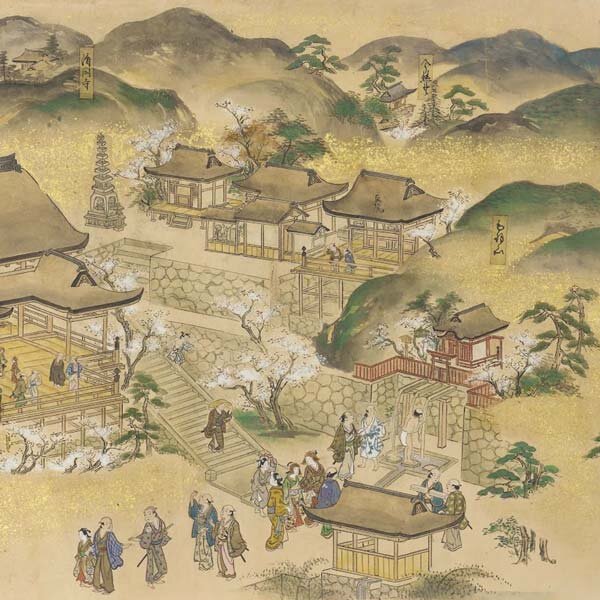

Dawn at Futamai-ga-ura by Utagawa Kunisada, 1832

Japanese woodblock prints, ukiyo-e, are a beloved form of art that hit enormous heights of popularity in the Edo period. At the time, Japan’s most successful and celebrated ukiyo-e artist, outshining even the now-legendary Hokusai himself, was Utagawa Kunisada. We take a look at why was Kunisada so cherished, and what made his artwork so uniquely cherished in Japan?

Kunisada: His Life and Art

Sanko no Uchi Hi by Utagawa Kunisada, 1859

Born in Tokyo (then called Edo) in 1786, Kunisada was the son of a moderately successful poet, who died very early in Kunisada’s life. The young artist began sketching very early and developed not only a passion but a clear skill in the craft which caught the eye of the master of the Utagawa school of ukiyo-e, Utagawa Toyokuni.

The Tale of Genji, Chapter 5, by Utagawa Kunisada, 1847

Thanks to the now legendary status of the works of Hokusai, many associate ukiyo-e with landscapes (see for example Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji), but during the Edo period, the most celebrated ukiyo-e paintings were depictions of kabuki actors, which is what Toyokuni himself was most known for, and comprised much of Kunisada’s own library of works. Kunisada is also renowned for his graphic and sometimes comic depictions of sexual scenes (that we might now label as pornographic), which may be one reason for why he is now far less well-remembered than Hokusai is. However, it was Hokusai who drew the infamous The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, which many point to as the origin of the tentacle in Japanese pornography. You can see more about the Essential Things to Know About Shunga Erotic Prints.

Imayo Oshi e Kagami by Utagawa Kunisada, 1859

He was also known as Utagawa Toyokuni III, under which name he would sign many of his works. Depending on the subject of his painting (landscape, kabuki, or other), Kunisada would sign with a different studio signature (Gototei for kabuki, or Kochoro for other things). For his more pornographic works, the works would be signed under the alias Matahei.

The Tale of Genji, Chapter 11, by Utagawa Kunisada, 1847

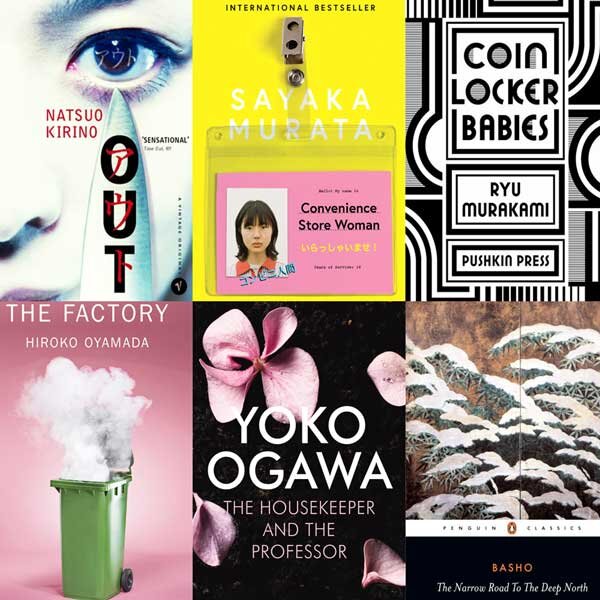

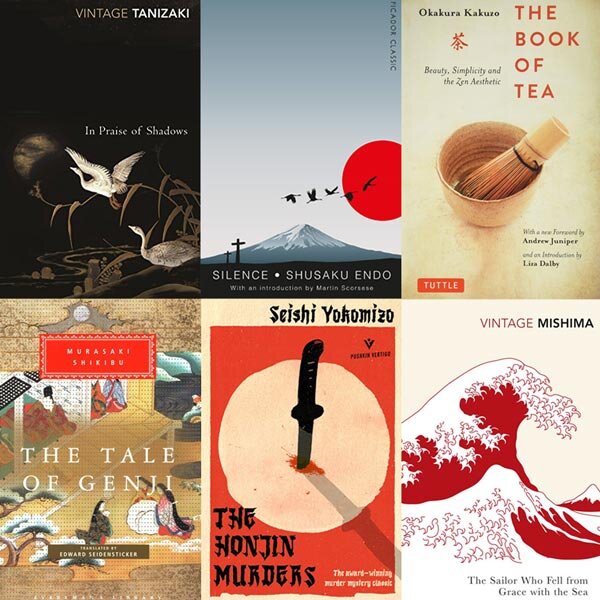

Kunisada’s prints mostly consisted of kabuki actors, the popular trend of the period, but as he continued to perfect his craft there was a growth in the number, and the experimental nature, of shunga works which Kunisada produced. He also painted a handful of landscape works, a few whose subjects were animals such as tigers His most popular subject was, by far, the human body. Kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, and beautiful women (bijin-ga) were among his specialties. At the time, artists’ depictions of scenes from The Tale of Genji were also popular, and it was Kunisada who led the charge here, producing a huge number of Genji-inspired works.

10 Popular Utagawa Kunisada Woodblock Prints

From his early days to his death, it is fascinating to see how Kunisada’s art evolved, both in terms of his own skill and what subjects he chose as his inspiration. Here are ten works which demonstrate the shifts in style and inspiration throughout Kunisada’s life.

1. Ichikawa Danjuro VII as Iga-no Jutaro (1823)

Ichikawa Danjuro VII as Iga-no Jutaro by Utagawa Kunisada, 1823

Created in 1823, this is Kunisada’s first known woodblock print. It depicts the kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjuro. Danjuro was the most celebrated actor of his time, and is still a legend of the kabuki world today, so a portrait of such a huge celebrity was certainly a smart place to begin a career as an artist! Compared to his later works, especially those of the same genre, it’s amazing to see the growth of his skill over the years. This first piece is lacking in detail, with no background to be seen. Instead, hand-written script surrounds the actor's face. There’s also an awkwardness to the detail on the actor’s costume. As for the character that Danjuro VII is depicting in the print, Iga-no Jutaro was a samurai and retainer to the Shogun, Soma no Yoshikado, and he has been portrayed by many an actor in plays throughout the history of kabuki. For some more background, check out 6 Things to Know About Kabuki Theater.

2. Tiger (1830)

Tiger by Utagawa Kunisada, 1830

Kunisada’s first well-known attempt at a non-human animal was simply titled Tiger. This particular depiction shows the tiger in an aggressive, predatory pose, which is immediately eye-catching as a more dynamic presentation of the legendary beast. Tigers in Japanese tradition are tightly connected to the Zen school of Buddhism; their sunny naps representing enlightenment and their careful method of grooming being an example of personal discipline. With this in mind, it’s doubly interesting how Kunisada has chosen a more ferocious and dominating pose for his tiger in this woodblock print.

3. View of Fuji from Miho Bay (1830)

View of Fuji from Miho Bay by Utagawa Kunisada, 1830

Another first for Kunisada, this woodblock depicts a view of Mt Fuji from Miho Bay. Before this stage in his career, Kunisada had been almost entirely on kabuki portraits. This print represents a huge change for Kunisada as he moved away from people to experiment with natural landscapes and scenery. It’s no surprise, given its prominence in so much Japanese art, that his first landscape would prominently present Mt Fuji. Though the fact that the painting is entirely made from blues and empty whites gives it a very ethereal and spiritual atmosphere, with Fuji itself almost appearing like a ghost in the distance of an early morning.

4. Blind Man Game - 47 Ronin (1847-50)

47 Ronin by Utagawa Kunisada, 1847

The tale of the Forty-seven Ronin is a true story about 47 masterless samurai who lost their daimyo to suicide when he was forced to end his own life after assaulting a court official. For one year they plotted their revenge, killed the official, and then all committed seppuku themselves. This story has become legend since it took place in 1702, and here Kunisada has depicted the ronin committing the act of revenge, with women cowering in fear and the court official helpless and blindfolded as three of the ronin ready their swords.

5. The Tale of Genji - Gust of Wind (1847-52)

The Tale of Genji - Gust of Wind by Utagawa Kunisada, 1847

In his later years, Kunisada had truly perfected his craft. The depth, blends of colour, and complex perspectives of his artwork truly set him apart. It was at this point in his career that Kunisada began painting works inspired by The Tale of Genji. Recreating iconic scenes from Shikibu’s novel in paintings, screens, lacquerware, and more has long been considered a high form of artistry in Japan and Kunisada’s Genji-inspired paintings prove to be some of his most inspired and picturesque. For fans of the story, see also The Tale of Genji in Japanese Art.

6. The Tale of Genji (1851-53)

The Tale of Genji by Utagawa Kunisada, 1851

During roughly the same period of his life, Kunisada completed more than one woodblock print inspired by The Tale of Genji. Not only is it considered by most historians to be the first Japanese novel, but it is also agreed to be the first novel written anywhere in the world. As such, The Tale of Genji is revered as one of Japan’s greatest works of art. With this in mind, it only makes sense for artists like Kunisada to recreate beloved scenes from the novel in vivid colour using their skills of portraiture and mood setting.

7. Sumo Spectators (1853)

Sumo Spectators by Utagawa Kunisada, 1853

It was very common for ukiyo-e artists of the Edo period to depict sumo wrestlers – almost as common as kabuki actors – but here is a unique twist on that tradition. This woodblock print shows a packed group of sumo spectators, with not a wrestler in sight. The perspective is from the side of the stage, with enough of the corner visible to make the perspective clear. This is easily Kunisada’s busiest piece, with the front row of spectators being drawn in enough details as to make each man unique. In the distance, faces gradually disappear but the business remains. This is certainly an original take on the tradition of ukiyo-e artists painting the sumo scene.

8. Murder Intent - Kabuki (1859)

Murder Intent by Utagawa Kunisada, 1859

Many of Kunisada’s most celebrated works of art depict intimate portraits of kabuki actors in character. These would be real actors who were popular on the stage during the late Edo period. But Kunisada also enjoyed recreating specific scenes from famous kabuki performances. Here, in Murder Intent, two actors can be seen in costume, their fluid motion captured in a moment not unlike by photograph. Their different stances, as well as their unique costume styles and colours, allow for a lot of dynamism within a single scene. For a ukiyo-e artist who went far behind drama to recreating horror, check out Why Utagawa Kuniyoshi was the Most Thrilling Ukiyo-e Master!

9. The Kabuki Actor Kawarasaki Gonjuro I (1861)

Kawarasaki Gonjuro I by Utagawa Kunisada, 1861

This woodblock print from 1861 is easily Utagawa Kunisada’s most famous woodblock print. But more than that, it serves as a fantastic comparison piece to his very first artwork: Ichikawa Danjuro VII as Iga-no Jutaro from 1823. Almost forty years after his first commercial work, The Kabuki actor Kawarasaki Gonjuro I shows an incredible maturation of Kunisada’s skill and eye for detail. This piece is beautifully detailed, busy and rather intense, suiting the atmosphere of kabuki perfectly.

10. Seascape (1832)

Dawn at Futamai-ga-ura by Utagawa Kunisada, 1832

Despite being created relatively early in Kunisada’s career, this woodblock print consists of such exquisite texture and detail. The perspective, depth, and attention to tiny details makes Seascape one of Kunisada’s most captivating and inspiring artworks. Kunisada rarely painted landscapes without focusing on human subjects but, when he did, he truly excelled at it.

ART | October 6, 2023