Coastal fisheries of Latin America and the Caribbean

Coastal fisheries of Latin America and the Caribbean

Coastal fisheries of Latin America and the Caribbean

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

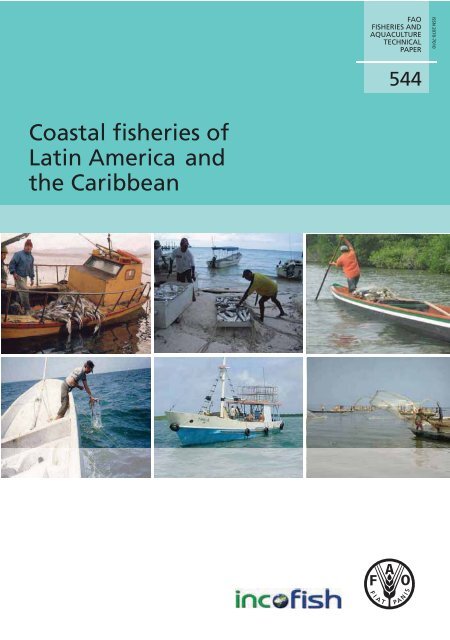

FAOFISHERIES ANDAQUACULTURETECHNICALPAPERISSN 2070-7010544<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>

Cover photos <strong>and</strong> credits (from top left clockwise):Fishing boat with bottom nets for hoki in Tierra del Fuego, Argentina (courtesy <strong>of</strong> Miguel S. Isla); l<strong>and</strong>ing products inHolbox, Quintana Roo, Mexico (courtesy <strong>of</strong> Mizue Oe); artisanal boat operating in Santa Marta, Colombia (courtesy<strong>of</strong> Mario Rueda); artisanal fisher fishing octopus in Yucatán, Mexico (courtesy <strong>of</strong> Manuel Solis); lobster boat withtraps in Cuba (Centro de Investigaciones Pesqueras de Cuba); artisanal boat operating in Santa Marta, Colombia(courtesy <strong>of</strong> Mario Rueda).

The designations employed <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> presentation <strong>of</strong> material in this information product donot imply <strong>the</strong> expression <strong>of</strong> any opinion whatsoever on <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Food <strong>and</strong> AgricultureOrganization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United Nations (FAO) concerning <strong>the</strong> legal or development status <strong>of</strong>any country, territory, city or area or <strong>of</strong> its authorities, or concerning <strong>the</strong> delimitation <strong>of</strong> itswhe<strong>the</strong>r or not <strong>the</strong>se have been patterned, does not imply that <strong>the</strong>se have been endorsed orrecommended by FAO in preference to o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> a similar nature that are not mentioned.The word “countries” appearing in <strong>the</strong> text refers to countries, territories <strong>and</strong> areas withoutdistinction.The views expressed in this information product are those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> author(s) <strong>and</strong> do notThe designations employed <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> presentation <strong>of</strong> material in <strong>the</strong> map(s) do not imply<strong>the</strong> expression <strong>of</strong> any opinion whatsoever on <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> FAO concerning <strong>the</strong> legal orconstitutional status <strong>of</strong> any country, territory or sea area, or concerning <strong>the</strong> delimitation <strong>of</strong>frontiers.ISBN 978-92-5-106722-2All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction <strong>and</strong> dissemination <strong>of</strong> material in thisinformation product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free <strong>of</strong> charge, uponrequest. Reproduction for resale or o<strong>the</strong>r commercial purposes, including educationalpurposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAOcopyright materials, <strong>and</strong> all o<strong>the</strong>r queries concerning rights <strong>and</strong> licences, should beaddressed by e-mail to copyright@fao.org or to <strong>the</strong> Chief, Publishing Policy <strong>and</strong>Viale Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy.© FAO 2011

DedicationThis document is dedicated to <strong>the</strong> memory <strong>of</strong> our colleague <strong>and</strong> friendBisessar Chakalall, former Fishery Officer in <strong>the</strong> Subregional Office for<strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> (SLC) <strong>and</strong> Secretary to <strong>the</strong> Western Central Atlantic FisheryCommission (WECAFC). Bisessar was an extraordinary human being whogave testimony to <strong>the</strong> values he believed in. He was brilliant <strong>and</strong> humble;dynamic <strong>and</strong> parsimonious; structured <strong>and</strong> spontaneous. He was an honest,generous <strong>and</strong> committed person. He had pr<strong>of</strong>ound interest in underst<strong>and</strong>ingo<strong>the</strong>rs, <strong>the</strong>ir culture <strong>and</strong> context, <strong>and</strong> a genuine interest in improving <strong>the</strong>well-being <strong>of</strong> fishing communities. Bisessar knew when to listen <strong>and</strong> whento speak out with his ideas <strong>and</strong> suggestions. He conducted himself with <strong>the</strong>passion <strong>and</strong> wisdom to intelligently explore life in all its dimensions. Bisessarwas an excellent <strong>and</strong> unique friend. His human legacy remains in our hearts<strong>and</strong> minds.

iiiPreparation <strong>of</strong> this documentThe idea <strong>of</strong> preparing a state-<strong>of</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-art document examining <strong>the</strong> assessment<strong>and</strong> management <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>grew naturally out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CoastFish conference <strong>of</strong> 2004 (see www.mda.cinvestav.mx/eventos/Coastfish/english/welcome). This interdisciplinaryconference, held in Mérida, Mexico, brought toge<strong>the</strong>r individuals frommany different institutions <strong>and</strong> organizations across <strong>the</strong> region, covering awide range <strong>of</strong> perspectives, in order to contribute to a better underst<strong>and</strong>ing<strong>of</strong> coastal small-scale <strong>fisheries</strong>. The focus was on fishery assessment <strong>and</strong>management, taking into account biological, socio-economic <strong>and</strong> policyissues, aiming to examine <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> information available for differentcountries <strong>and</strong> to identify <strong>the</strong> gaps in knowledge <strong>and</strong> management. The goalultimately was to use this underst<strong>and</strong>ing to determine desirable directionsfor future fishery research, as well as governance <strong>and</strong> managementapproaches to moving towards sustainable <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>the</strong> region. This goalremains valid for this document as well.This document has been prepared as an initiative <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> editors – S. Salas,R. Chuenpagdee, A. Charles <strong>and</strong> J.C. Seijo – in cooperation with a strongset <strong>of</strong> authors writing about coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> in twelve countries across <strong>Latin</strong><strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>. Writing <strong>and</strong> compilation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> document weresupported by <strong>the</strong> European Union through <strong>the</strong> project Integrating MultipleDem<strong>and</strong>s on <strong>Coastal</strong> Zones with Emphasis on Aquatic Ecosystems <strong>and</strong>Fisheries (INCOFISH). The Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>United Nations (FAO) coordinated <strong>the</strong> final pro<strong>of</strong>reading, publishing <strong>and</strong>distribution. References in this document follow international bibliographicst<strong>and</strong>ards ra<strong>the</strong>r than FAO house style.

ivAbstractThe importance <strong>of</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> for coastal communities <strong>and</strong> livelihoods in <strong>Latin</strong><strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> (LAC) is well documented. This is particularly<strong>the</strong> case for ‘coastal <strong>fisheries</strong>’, including subsistence, traditional (artisanal) <strong>and</strong>advanced artisanal (or semi-industrial) varieties. There are, however, major gapsin knowledge about <strong>the</strong>se <strong>fisheries</strong>, <strong>and</strong> major challenges in <strong>the</strong>ir assessment<strong>and</strong> management. Therein lies <strong>the</strong> key <strong>the</strong>me <strong>of</strong> this document, which seeks tocontribute to a better underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>the</strong> LAC region, as wellas to generate discussion about ways to move towards sustainable <strong>fisheries</strong>. Thedocument includes three main components. First, an introductory chapter providesan overview <strong>of</strong> general trends in <strong>the</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> LAC countries, as well assome <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> key challenges <strong>the</strong>y are facing in terms <strong>of</strong> sustainability. Second, a set<strong>of</strong> twelve chapters each reporting on <strong>the</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> one country in <strong>Latin</strong><strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>, collectively covering <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> each main subregion:<strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> isl<strong>and</strong>s (Barbados, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Grenada, PuertoRico, Trinidad <strong>and</strong> Tobago), North <strong>and</strong> Central <strong>America</strong> (Costa Rica, Mexico) <strong>and</strong>South <strong>America</strong> (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Uruguay). All <strong>the</strong>se country-specificchapters follow an integrated approach, to <strong>the</strong> extent possible, covering aspectsranging from <strong>the</strong> biological to <strong>the</strong> socio-economic. Third, <strong>the</strong> final component <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> document contains a syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong> information from <strong>the</strong> countries examined, ananalysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> main issues <strong>and</strong> challenges faced by <strong>the</strong> various <strong>fisheries</strong>, an outline<strong>of</strong> policy directions to improve <strong>fisheries</strong> management systems in <strong>the</strong> LAC region,identification <strong>of</strong> routes toward more integrated approaches for coastal <strong>fisheries</strong>management, <strong>and</strong> recommendations for ‘ways forward’ in dealing with fisheryassessment <strong>and</strong> governance issues in <strong>the</strong> region.Salas, S.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Charles, A.; Seijo, J.C. (eds).<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>.FAO Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Aquaculture Technical Paper. No. 544. Rome, FAO. 2011. 430p.

vContentsDedicationPreparation <strong>of</strong> this documentAbstractAcknowledgementsPrefaceiiiivviiviii1. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>:issues <strong>and</strong> trends 1Silvia Salas, Ratana Chuenpagdee, Anthony Charles <strong>and</strong> Juan Carlos Seijo2. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Argentina 13Inés Elías, Claudia Carozza, Edgardo E. Di Giácomo, Miguel S. Isla,J.M. (Lobo) Orensanz, Ana María Parma, Raúl C. Pereiro,M. Raquel Perier, Ricardo G. Perrotta, María E. Ré <strong>and</strong> Claudio Ruarte3. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Barbados 49Patrick McConney4. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Brazil 73Marcelo Vasconcellos, Antonio Carlos Diegues <strong>and</strong>Daniela Coswig Kalikoski5. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Colombia 117Mario Rueda, Jacobo Blanco, Juan Carlos Narváez, Efraín Viloria <strong>and</strong>Claudia Stella Beltrán.6. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Costa Rica 137Ángel Herrera-Ulloa, Luis Villalobos-Chacón, José Palacios-Villegas,Rigoberto Viquez-Portuguéz <strong>and</strong> Guillermo Oro-Marcos7. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Cuba 155Serv<strong>and</strong>o V. Valle, Mireya Sosa, Rafael Puga, Luis Font <strong>and</strong> Regla Duthit8. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dominican Republic 175Alej<strong>and</strong>ro Herrera, Liliana Betancourt, Miguel Silva, Patricia Lamelas<strong>and</strong> Alba Melo9. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Grenada 219Rol<strong>and</strong> Baldeo10. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Mexico 231José Ignacio Fernández, Porfirio Álvarez-Torres, FranciscoArreguín-Sánchez, Luís G. López-Lemus, Germán Ponce, AntonioDíaz-de-León, Enrique Arcos-Huitrón <strong>and</strong> Pablo del Monte-Luna

vi11. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Puerto Rico 285Mónica Valle-Esquivel, Manoj Shivlani, Daniel Matos-Caraballo <strong>and</strong>David J. Die12. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Trinidad <strong>and</strong> Tobago 315Elizabeth Mohammed, Lara Ferreira, Suzuette Soomai, Louanna Martin<strong>and</strong> Christine Chan A. Shing13. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Uruguay 357Omar Defeo, Pablo Puig, Sebastián Horta <strong>and</strong> Anita de Álava14. Assessing <strong>and</strong> managing coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>: underlying patterns <strong>and</strong> trends 385Ratana Chuenpagdee, Silvia Salas, Anthony Charles <strong>and</strong>Juan Carlos Seijo15. Toward sustainability for coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>: effective governance <strong>and</strong> healthyecosystems 403Juan Carlos Seijo, Anthony Charles, Ratana Chuenpagdee <strong>and</strong> Silvia Salas16. Concluding thoughts: coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> 423Anthony Charles, Silvia Salas, Juan Carlos Seijo <strong>and</strong> Ratana ChuenpagdeeList <strong>of</strong> contributors 427Editors’ pr<strong>of</strong>ile 429

viiAcknowledgementsThis document is a product <strong>of</strong> collaboration among a wide range <strong>of</strong> scientists <strong>and</strong>researchers in <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>, who share common interests <strong>and</strong>concerns about coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> well-being <strong>of</strong> coastal communities in <strong>the</strong>region. We want to thank first <strong>the</strong> authors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country-specific chapters in thisdocument, who have continued to believe in <strong>the</strong> project <strong>of</strong> this document, <strong>and</strong>made strong efforts to ga<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> available information about coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> in<strong>the</strong>ir respective countries. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contributors presented <strong>the</strong>ir initial resultsat <strong>the</strong> CoastFish conference. We are also grateful to conference participantswho contributed to <strong>the</strong> discussion on existing assessment tools <strong>and</strong> managementapproaches – highlights <strong>of</strong> this discussion are included in this volume.The document could have not been produced without funding from <strong>the</strong>European Union through <strong>the</strong> project Integrating Multiple Dem<strong>and</strong>s on <strong>Coastal</strong>Zones with Emphasis on Aquatic Ecosystems <strong>and</strong> Fisheries (INCOFISH) (ProjectNo. INCO 003739). We also thank <strong>the</strong> Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>United Nations (FAO) for support at <strong>the</strong> publication stage. We thank Drs RainerFroese <strong>and</strong> Silvia Opitz (INCOFISH), Dr Cornelia Naun (European Union), <strong>and</strong>Dr Kevern Cochrane (FAO) for <strong>the</strong>ir strong support <strong>and</strong> encouragement.We are grateful to Kathryn Goetting, Carlos Zapata Araujo, Miguel A.Cabrera <strong>and</strong> Patricia González for <strong>the</strong>ir help with <strong>the</strong> translation, formatting <strong>and</strong>editing. Much appreciated as well are <strong>the</strong> patient efforts <strong>of</strong> Kevern Cochrane <strong>and</strong>Johanne Fischer at FAO in guiding <strong>the</strong> document through to publication, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>Maria Giannini <strong>and</strong> Michèle S. Kautenberger-Longo, also at FAO, for excellentpro<strong>of</strong>reading <strong>and</strong> formatting. Finally, Anthony Charles acknowledges financialsupport from a research grant from <strong>the</strong> Natural Sciences <strong>and</strong> Engineering ResearchCouncil <strong>of</strong> Canada, <strong>and</strong> Ratana Chuenpagdee is grateful for financial support from<strong>the</strong> Social Sciences <strong>and</strong> Humanities Research Council <strong>of</strong> Canada <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> CanadaResearch Chairs Program.

viiiPrefaceAlong <strong>the</strong> coasts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> (LAC), <strong>fisheries</strong> areinherently complex – notably as a result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> heterogeneity <strong>of</strong> gears, boats <strong>and</strong>species, as well as <strong>the</strong> diversity <strong>of</strong> geophysical, bio-ecological <strong>and</strong> socio-economiccharacteristics. <strong>Coastal</strong> fishers in <strong>the</strong> region are especially vulnerable to <strong>the</strong> impacts<strong>of</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> declines, given <strong>the</strong>ir livelihood <strong>and</strong> income dependence on localresources. Meanwhile, only limited technical <strong>and</strong> financial support exists for <strong>the</strong>assessment <strong>and</strong> management <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong>.As a result, while <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>the</strong> LAC region is clear,<strong>the</strong>ir assessment is highly challenging. Limitations in <strong>the</strong> knowledge base forcoastal <strong>fisheries</strong> have become more <strong>and</strong> more evident. Within <strong>the</strong> environments inwhich coastal small-scale <strong>fisheries</strong> operate, data are typically lacking or relativelyless available <strong>and</strong>, in particular, quantitative information is relatively sparse. Forinstance, while information about <strong>fisheries</strong> l<strong>and</strong>ings has regularly been ga<strong>the</strong>redat a national level <strong>and</strong> aggregated to regional <strong>and</strong> global levels by internationalorganizations like FAO, <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>of</strong>ten no distinction made between l<strong>and</strong>ings fromsmall-scale <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>and</strong> from larger-scale commercial ventures. There are alsogaps in knowledge about <strong>the</strong> various management methods used in <strong>the</strong> region.The shortfall between <strong>the</strong> information available <strong>and</strong> that needed for properunderst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> makes it difficult to determine managementschemes that can best fit <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> such <strong>fisheries</strong>.We hope that this document represents a significant contribution to filling some<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> many information gaps on fishery assessment <strong>and</strong> management in LACcoastal <strong>fisheries</strong>. Over <strong>the</strong> years, <strong>the</strong>re have been remarkably few examinations<strong>of</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>the</strong> region, <strong>and</strong> certainly not many taking an integrated <strong>and</strong> broadbasedperspective. This document can be seen as complementing past publications,such as those <strong>of</strong> FAO <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> World Bank, among o<strong>the</strong>rs, while also providing anintegrated approach to examining <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> region. We hope readers will find<strong>the</strong> volume useful, <strong>and</strong> that it might contribute both to increasing <strong>the</strong> attentionpaid to coastal small-scale <strong>fisheries</strong> across <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>and</strong>to identifying <strong>the</strong> ingredients for <strong>the</strong>ir successful management <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir long-termsustainability.The editors

11. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong><strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>region: issues <strong>and</strong> trendsSilvia Salas,* Ratana Chuenpagdee, Anthony Charles <strong>and</strong> Juan Carlos SeijoSalas, S., Chuenpagdee, R., Charles, A. <strong>and</strong> Seijo, J.C. (eds). 2011. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong><strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> region: issues <strong>and</strong> trends. In S. Salas, R. Chuenpagdee, A. Charles<strong>and</strong> J.C. Seijo (eds). <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>. FAO Fisheries <strong>and</strong>Aquaculture Technical Paper. No. 544. Rome, FAO. pp. 1–12.1. Introduction 12. Major trends in coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> 33. Factors affecting sustainability <strong>of</strong> LAC coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> 63.1 Fisheries complexities 73.2 Growing dem<strong>and</strong> for scarce resources 73.3 Different incentives 83.4 Stock fluctuations 83.5 Lack <strong>of</strong> governance structures 94. Concluding remarks 9References 101. INTRODUCTIONThe importance <strong>of</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> for coastal communities in <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Caribbean</strong> (LAC) has been highlighted in many forums <strong>and</strong> reports, includingthose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United Nations (FAO)<strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r development agencies such as <strong>the</strong> World Bank <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Organisationfor Economic Co-operation <strong>and</strong> Development (OECD). <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>and</strong> smallscalefishers <strong>of</strong>ten have considerable livelihood <strong>and</strong> income dependency on localresources – making <strong>the</strong>m highly vulnerable to negative trends in <strong>the</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong>,such as declining catches <strong>and</strong> degrading habitats, <strong>and</strong> particularly to <strong>the</strong> risk <strong>of</strong>downturns <strong>and</strong> collapse (Staples et al., 2004; World Bank, 2004; Bené et al., 2007).* Contact information: Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados, Unidad Mérida. Mérida,Yucatán, Mexico. E-mail: ssalas@mda.cinvestav.mx

2<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>These realities reinforce <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing, assessing <strong>and</strong>effectively managing coastal <strong>fisheries</strong>. This is <strong>the</strong> key <strong>the</strong>me <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> document –to examine <strong>the</strong> various approaches <strong>and</strong> challenges arising in <strong>the</strong> assessment <strong>and</strong>management <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> within <strong>the</strong> LAC region. For <strong>the</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong> thisdocument, <strong>the</strong> term ‘coastal <strong>fisheries</strong>’ refers to three main types: subsistence<strong>fisheries</strong>, traditional <strong>fisheries</strong> (artisanal), <strong>and</strong> advanced artisanal (or semi-industrial)<strong>fisheries</strong>. The adaptability <strong>of</strong> fishers, which enables <strong>the</strong>m to switch gears <strong>and</strong>target species, makes it difficult in some cases to differentiate among <strong>the</strong>se threetypes, but broadly <strong>the</strong> main distinction made here is between coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>and</strong>industrial or recreational <strong>fisheries</strong>. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> tend to share certain features,such as high mobility <strong>of</strong> fishers, transboundary issues related to shared resources,high competition among user groups, seasonal use <strong>of</strong> resources, <strong>and</strong> multiplelivelihoods (Beltran, 2005; Agüero <strong>and</strong> Claverí, 2007; Salas et al., 2007; Chakalallet al., 2007).This volume strives to contribute to a better underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong>in <strong>the</strong> region, in terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir assessment <strong>and</strong> management, as well as to generatediscussion about ways to move towards sustainable <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>the</strong> region. Theheart <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> document is a set <strong>of</strong> twelve chapters each reporting on <strong>the</strong> coastal<strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> one country in <strong>the</strong> LAC region. Specifically, <strong>the</strong>se ‘country chapters’include information on <strong>the</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> main subregions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong><strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>: <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> isl<strong>and</strong>s (Barbados, Cuba, DominicanRepublic, Grenada, Puerto Rico, Trinidad <strong>and</strong> Tobago), North <strong>and</strong> Central<strong>America</strong> (Costa Rica, Mexico) <strong>and</strong> South <strong>America</strong> (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia,Uruguay).The twelve countries included in <strong>the</strong> document provide reasonable geographicalcoverage, but <strong>the</strong> information presented herein is certainly not exhaustive. Theheterogeneity <strong>and</strong> complexity <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>the</strong> LAC region is clear,given its large number <strong>of</strong> countries <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir diverse geophysical, bio-ecological<strong>and</strong> socio-economic characteristics. Accordingly, this document reflects only asampling <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> region’s <strong>fisheries</strong> – but it does highlight many issues <strong>and</strong> challengesshared by <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>the</strong> region, especially regarding assessment <strong>and</strong> management.It also provides an analytical discussion <strong>and</strong> directions for future fishery research<strong>and</strong> management.The document is organized into three main sections. In this introductorychapter we provide an overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> general trends in <strong>the</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>LAC countries as well as some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> key challenges <strong>the</strong>y are facing in terms <strong>of</strong>sustainability.Following this is <strong>the</strong> set <strong>of</strong> 12 ‘country chapters’ described above, which presenta range <strong>of</strong> contexts, <strong>and</strong> discuss common problems as well as particularities thatillustrate <strong>the</strong> complexity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>the</strong> region. All <strong>the</strong> country-specificchapters follow <strong>the</strong> same format, to <strong>the</strong> extent possible, in terms <strong>of</strong> content, rangingfrom biological to socio-economic information. The focus <strong>of</strong> each one varies,however, depending on key characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>the</strong> correspondingcountry, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> disciplines <strong>and</strong> specialization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authors. Each also

4<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>The major contribution to <strong>the</strong> region’s total l<strong>and</strong>ings comes from pelagicspecies l<strong>and</strong>ed by industrial <strong>fisheries</strong>. For example, <strong>the</strong> fluctuations in l<strong>and</strong>ings,such as <strong>the</strong> sharp rises in 1970, 1994 <strong>and</strong> 2000 <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> declines in 1972, 1983 <strong>and</strong>1994 were due largely to fluctuations on l<strong>and</strong>ings from purse seine <strong>fisheries</strong> inPeru <strong>and</strong> Chile. Also, high squid l<strong>and</strong>ings in <strong>the</strong>se two countries in recent yearscontributed significantly to <strong>the</strong> total increase. Similar to Peru <strong>and</strong> Chile, catchesfrom Mexico come mainly from purse seines (about 42% in 2004). On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rh<strong>and</strong>, in Argentina <strong>and</strong> Brazil, <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>ings come from trawling(about 72% <strong>and</strong> 50% <strong>of</strong> total country l<strong>and</strong>ings in 2004, respectively).If we focus on coastal l<strong>and</strong>ings, by excluding from <strong>the</strong> data catches from gearsoperating mostly in <strong>of</strong>fshore areas (i.e. bottom trawls, midwater trawls <strong>and</strong> purseseines), <strong>the</strong> contributions from Peru <strong>and</strong> Chile are reduced from 84% to about44% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total within our reference group <strong>of</strong> 14 countries. While this does notchange <strong>the</strong> top five countries in Table 1, in terms <strong>of</strong> total l<strong>and</strong>ings, <strong>the</strong> importance<strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> becomes evident in countries like <strong>the</strong> Dominican Republic,Grenada, Puerto Rico, <strong>and</strong> Trinidad <strong>and</strong> Tobago, in each <strong>of</strong> which l<strong>and</strong>ings fromgears used mostly in coastal waters exceed 50% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total l<strong>and</strong>ings for thatcountry (Table 1). Peru <strong>and</strong> Chile, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, provide far less <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ircatches from coastal <strong>fisheries</strong>, with l<strong>and</strong>ings from this sector contributing onlyabout 2% <strong>and</strong> 9% respectively to <strong>the</strong> total for each country. Incidentally, <strong>the</strong>seproportions are <strong>the</strong> lowest among <strong>the</strong> LAC countries examined here.Mexico <strong>and</strong> most countries in Central <strong>America</strong> have fleets both on <strong>the</strong> Pacific<strong>and</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> coasts, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y are highly dependent on coastal <strong>fisheries</strong>, especiallyas a source <strong>of</strong> jobs <strong>and</strong> food. Reports by FAO (2000) for <strong>the</strong>se countries indicatethat catches appear to be higher on <strong>the</strong> Pacific than on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> coasts in mostcases. In <strong>the</strong> latter, a lower volume seems to be compensated for by <strong>the</strong> capture <strong>of</strong>pr<strong>of</strong>itable species like conch, lobster <strong>and</strong> shrimp, among o<strong>the</strong>rs, which contributesignificant foreign currency to <strong>the</strong>se countries. Total export <strong>of</strong> catches in <strong>the</strong> LACregion (excluding aquaculture) by <strong>the</strong> year 2001 was close to US$7 million; fivecountries made up 73% <strong>of</strong> this contribution (Agüero <strong>and</strong> Claverí, 2007).Accurate figures on fishing effort in coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> LAC region aregenerally not available, <strong>and</strong> when <strong>the</strong>y do exist <strong>the</strong>re is typically a shortage <strong>of</strong>consistent information. Even though catch records began in <strong>the</strong> 1950s in somecountries, information on fishing effort started to be collected much later. Suchdata are important in <strong>the</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong> fishing capacity <strong>and</strong> labour capacityrelative to catch trends. In general, <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> people involved in fishing <strong>and</strong>fish farming has more than doubled in <strong>the</strong> last three decades (FAO, 2006a; Salaset al., 2007), with many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se people entering <strong>the</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> industry. Incontrast to global trends (Figure 1), it is evident when evaluating l<strong>and</strong>ings onlyfrom coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> that between <strong>the</strong> early 1970s <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> mid-1990s <strong>the</strong>re wasan increasing trend in catches in South <strong>America</strong>, with a declining trend after thisperiod (Figure 2). In <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>, <strong>the</strong> trend has been generally upward for threedecades, afterward a sharp decline has changed <strong>the</strong> general trend.

<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> region: issues <strong>and</strong> trends 5TABLE 1Catches for those countries included in this document plus Peru <strong>and</strong> Chile in 2004. Totall<strong>and</strong>ings integrate catches from all gears 1 <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>ings from ‘coastal gears’ 2 include allgears except bottom trawl, mid-water trawl <strong>and</strong> purse seinesCountryTotal l<strong>and</strong>ingsfor all gears(‘000 tonnes)% <strong>of</strong> total l<strong>and</strong>ings<strong>of</strong> all listedcountriesL<strong>and</strong>ings from‘coastal gears’only (tonnes)% <strong>of</strong> coastall<strong>and</strong>ings intotal for <strong>the</strong>countryPeru 9 611.94 52.68 151.27 1.57Chile 5 317.31 29.14 492.18 9.26Mexico 1 286.57 7.06 134.60 10.46Argentina 945.94 5.18 187.36 19.81Brazil 746.21 4.09 130.66 17.51Colombia 124.95 0.68 13.82 11.06Uruguay 122.98 0.67 15.38 12.51Cuba 36.14 0.20 16.21 44.85Costa Rica 20.85 0.11 3.64 17.46Dominican Republic 14.22 0.08 7.28 51.20Trinidad <strong>and</strong> Tobago 1 10.03 0.06 5.10 50.84Puerto Rico 6.12 0.03 3.50 57.18Barbados 1 2.14 0.01 0.92 43.00Grenada 1 2.03 0.01 1.80 89.00Source: 1 FAO (2004: http://www.fao.org/fishery/geoinfo/en); 2 data from Sea Around Us, 2004 (www.Seaaroundus.org)adapting FAO data.As in o<strong>the</strong>r parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong> expansion in catches in <strong>the</strong> LAC region hasbeen due to technological development <strong>and</strong> an increase in <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fleet,an expansion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fishery workforce, exploration <strong>of</strong> new fishing grounds, <strong>and</strong>related impacts <strong>of</strong> government financial transfers (FAO, 2006a; OECD, 2006;Gréboval, 2007). In <strong>the</strong> last decade, in many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se countries <strong>the</strong> most importantresources are considered to be at <strong>the</strong>ir maximum level <strong>of</strong> exploitation (WorldBank, 2004; FAO, 2006b; Agüero <strong>and</strong> Claverí, 2007). Despite this situation, <strong>the</strong>status <strong>of</strong> many <strong>fisheries</strong> in <strong>the</strong> region is poorly known. Agüero (1992) states thatone <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> problems <strong>the</strong>se countries face has been <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> consistency in <strong>the</strong>way catches have been recorded <strong>and</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> analysed. Fisheries institutes inmany <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se countries were created in <strong>the</strong> 1960s to conduct research, but <strong>the</strong>yhave not achieved sufficient technical capacity (human <strong>and</strong> logistic) due to limitedfinancial support (Agüero <strong>and</strong> Claverí, 2007).

6<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>FIGURE 2L<strong>and</strong>ing trends <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> by area from main countries that operate in<strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>Source: Sea Around Us project database (www.seaaroundus.org).3. FACTORS AFFECTING SUSTAINABILITY OF LAC COASTAL FISHERIESMany factors have contributed to <strong>the</strong> unsustainability <strong>of</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>sein turn have led to excess capacity (Gréboval, 2002; Swan <strong>and</strong> Gréboval, 2004;Gréboval, 2007). These factors include: (i) a lack <strong>of</strong> solid governance structures;(ii) fishery complexities, incomplete knowledge <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> associated uncertainties;(iii) inadequate incentives <strong>and</strong> subsidies that stimulate overcapacity; (iv) stockfluctuations due to natural causes; (v) growing dem<strong>and</strong> for limited fish resources;<strong>and</strong> (vi) poverty <strong>and</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong> alternatives for coastal development. These factorsare examined below as well as throughout <strong>the</strong> document.

<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> region: issues <strong>and</strong> trends 73.1 Fisheries complexitiesScientific literature <strong>and</strong> public media have extensively reported problems that<strong>fisheries</strong> in many areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world are facing. While it is generally known thatoverexploitation, habitat degradation <strong>and</strong> unintended catches <strong>and</strong> discards arecommon causes <strong>of</strong> such crises, <strong>the</strong>ir effects on <strong>the</strong> ecosystem <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> economy <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> nations involved, especially in <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong>, are not alwaysproperly addressed. This is due mainly to <strong>the</strong> complexity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se <strong>fisheries</strong>, whichmakes assessment <strong>and</strong> management difficult (Cochrane, 1999; Mahon et al.,2008, 2009). For instance, many coastal fishers switch among alternative fisheryresources using various fishing gears throughout <strong>the</strong> year, making it difficult todetermine fishing effort. Some fishers engage in o<strong>the</strong>r occupations such as tourism,salt mining or aquaculture to supplement <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>fisheries</strong> income. As coastal areasaround <strong>the</strong> world continue to attract migrants, conflicts between various uses <strong>of</strong>coastal resources accelerate <strong>and</strong> consequently affect <strong>the</strong> livelihoods <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> coastalcommunities. Balancing between uses <strong>and</strong> conservation in coastal areas has thusbecome more challenging, especially when information to foster comprehensiveunderst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> those <strong>fisheries</strong> is insufficient.3.2 Growing dem<strong>and</strong> for scarce resourcesIn <strong>the</strong> last few decades <strong>the</strong> increase in food consumption has been oriented toprotein intake in many countries, especially in Europe <strong>and</strong> Asia. This trend hasbeen favoured by an improvement in food technology which has provided addedvalue to diverse products including those coming from <strong>the</strong> sea. According to FAO,<strong>the</strong> per capita consumption <strong>of</strong> fish in <strong>the</strong> world has increased from 9 kg in 1961 to16.5 kg in 2003 (FAO, 2006b). Even though consumption in developing nations islower than that <strong>of</strong> developed nations, <strong>the</strong> market still <strong>of</strong>fers incentives to enter <strong>the</strong>fishing industry. The increase in tourism in coastal areas also keeps up <strong>the</strong> dem<strong>and</strong>for marine products.An increase in coastal population has resulted in steeper competition fora reduced level <strong>of</strong> resources. At <strong>the</strong> same time, degradation <strong>of</strong> habitats from<strong>the</strong> expansion <strong>of</strong> different activities along <strong>the</strong> coast has had an impact on <strong>the</strong>corresponding ecosystems, on <strong>the</strong>ir resources, <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> people depending on<strong>the</strong>m.The sharp rise in <strong>fisheries</strong> production outlined above has been caused bymany factors, including uncontrolled capacity in <strong>the</strong> industry, technologicalimprovements, an increase in dem<strong>and</strong> for seafood, <strong>and</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong> governance. Ageneral pattern <strong>of</strong> overcapacity <strong>and</strong> resource degradation has been reported incountries from <strong>the</strong> LAC region (Ehrhardt, 2007; Ormaza, 2007; Salas et al., 2007;Vasconcellos et al., 2007; Wosnitza et al., 2007). It is important to note that whilesome general patterns can be observed in <strong>the</strong> whole LAC region, <strong>the</strong> situation ineach country is context specific, <strong>and</strong> an underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> issues <strong>and</strong> challengesfaced in each location, taking into account particular geopolitical conditions, couldprovide useful insights for <strong>the</strong> whole region (Agüero <strong>and</strong> Claverí, 2007; Chakalallet al., 2007). This, we hope, will be one key outcome <strong>of</strong> this document.

8<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>3.3 Different incentivesOne <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> factors promoting growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fishing industry is <strong>the</strong> intervention <strong>of</strong>government through different types <strong>of</strong> financial transfers. Government financialtransfers (GFT) are defined by <strong>the</strong> OECD (2006) as “<strong>the</strong> monetary value <strong>of</strong>government interventions associated with <strong>fisheries</strong> policies” <strong>and</strong> include marketprice support, untaxed resource rent, negative subsidies, as well as infrastructureexpenditure. Unfortunately, limited information exists on financial transfersapplied in <strong>the</strong> LAC countries <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir impacts; most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> interventions reportedin <strong>the</strong> country chapters <strong>of</strong> this document have to do with subsidies.Indeed, <strong>the</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> subsidies in coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> is discussed in seven <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> chapters (Argentina, Mexico, Trinidad <strong>and</strong> Tobago, Costa Rica,Grenada, Brazil <strong>and</strong> Barbados). Among <strong>the</strong> subsidies reported are: (i) grants for<strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> new vessels, traps, aggregating devices, etc.; (ii) grants for <strong>the</strong>modernization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fleets; (iii) preferential credits; <strong>and</strong> (iv) reduced prices forpurchased inputs (e.g. fuel, bait <strong>and</strong> ice). The impact <strong>of</strong> subsidies on sustainabilitydepends on <strong>the</strong> dynamics <strong>of</strong> fleet capacity <strong>and</strong> effort <strong>of</strong> both small-scale as well asindustrial vessels. To <strong>the</strong> extent that subsidies reduce operating costs in <strong>fisheries</strong>,this tends to artificially generate pr<strong>of</strong>its that fur<strong>the</strong>r stimulate fishing capacitygrowth, lower biomass levels <strong>and</strong> raise competition.3.4 Stock fluctuationsClearly, independent <strong>of</strong> fishing activity, stocks will fluctuate in <strong>the</strong> short <strong>and</strong>long run due to natural causes. For pelagic resources, major stock fluctuationsoccurred even prior to human exploitation (Soutar <strong>and</strong> Isaacs, 1974). Thesefluctuations have been best documented in relation to <strong>the</strong> El Niño-Sou<strong>the</strong>rnOscillation (ENSO) climatic phenomenon, especially as it affects <strong>the</strong> production<strong>of</strong> small pelagic fishes in <strong>the</strong> eastern Pacific (e.g. Lluch-Belda et al., 1989), butalso as it impacts o<strong>the</strong>r resources <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r geographic areas. Similar climaticforcing factors have been affecting marine production systems on <strong>the</strong> globallevel (Kawasaki, 1992; Klyashtorin, 2001), <strong>and</strong> long-term fluctuations will bereinforced by climate change (Kelly, 1983). Thus, although ‘decadal’ periodicitiesare frequently mentioned in <strong>the</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> literature (e.g. Zwanenberg et al., 2002),Klyashtorin (2001) suggests that natural cycles in productivity <strong>of</strong> around 50 to 60years duration are likely to be dominant.<strong>Coastal</strong> fishery resources are also vulnerable to o<strong>the</strong>r human activities that mayaffect critical habitats <strong>and</strong>/or biological <strong>and</strong> biophysical processes (e.g. Spalding<strong>and</strong> Kramer, 2004). With respect to <strong>the</strong> latter, <strong>the</strong> long-term role <strong>of</strong> environmentalchange in <strong>fisheries</strong> has become easier to observe in recent years now that <strong>fisheries</strong>data series more commonly exceed a half century in duration. However, our abilityto discriminate between natural environmental changes, <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> fishing, <strong>and</strong><strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r human activities remains poor.

<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> region: issues <strong>and</strong> trends 93.5 Lack <strong>of</strong> governance structuresAccording to Kooiman et al. (2005), governance is beyond government <strong>and</strong> broaderthan management in that it involves problem solving, creation <strong>of</strong> opportunities,<strong>and</strong> interactions. Mahon et al. (2008) advocate an interactive <strong>fisheries</strong> governanceperspective, which involves a dynamic <strong>and</strong> complex fish chain, leading from <strong>the</strong>resource <strong>and</strong> its supporting ecosystem to <strong>the</strong> global marketplace <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> localconsumer. The dynamics <strong>of</strong> this chain need to be balanced as <strong>the</strong> system respondsto a variety <strong>of</strong> stimuli.Interactions within complex <strong>fisheries</strong> systems in many cases have beenignored when <strong>fisheries</strong> resources are examined in an isolated manner <strong>and</strong> publicparticipation in problem solving <strong>and</strong> creating opportunities are discouraged(Castilla <strong>and</strong> Defeo, 2005; Charles, 2001; Garcia <strong>and</strong> Charles, 2008; Mahon et al.,2008). Given <strong>the</strong> current context <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> high diversity that characterize coastal<strong>fisheries</strong> in LAC, alternative forms <strong>of</strong> governance are required, particularly todevelop local institutions that help increase social capital <strong>and</strong> develop strategiessuitable to <strong>the</strong> social, economic <strong>and</strong> political contexts faced by <strong>the</strong> correspondingfisher groups. For example, many chapters throughout <strong>the</strong> document place specialemphasis on <strong>the</strong> need for collective access rights for fishing communities in orderto promote co-management. This approach highlights resource use <strong>and</strong> accessamong <strong>the</strong> challenges <strong>fisheries</strong> face in <strong>the</strong> move towards good governance.4. CONCLUDING REMARKSAs fishing pressure has imposed significant problems on <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>irmanagers across most LAC countries, various degrees <strong>of</strong> response, in terms <strong>of</strong>fishery management <strong>and</strong> assessment, have been developed. However, many gapsstill exist in <strong>the</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> issues, as will be discussed in <strong>the</strong> differentcountry chapters. These gaps arise as a result <strong>of</strong> some key limitations.First, with regard to assessment, <strong>the</strong> limited qualitative <strong>and</strong> quantitativeinformation on coastal <strong>and</strong> small-scale <strong>fisheries</strong> is evident. In many countries,<strong>of</strong>ficial statistics make no distinction between l<strong>and</strong>ings from small-scale <strong>fisheries</strong><strong>and</strong> from larger-scale commercial ventures. Although l<strong>and</strong>ings from <strong>the</strong>se twosectors can be distinguished based on gear use in some cases (as attempted inTable 1), <strong>the</strong>re is generally a lack <strong>of</strong> permanent programmes to monitor catchesfrom <strong>the</strong>se <strong>fisheries</strong>. Problems associated with evaluation are also common,exacerbated by limited financial support for research.Second, <strong>the</strong> ‘management tool-kit’ appropriate for small-scale <strong>fisheries</strong> ismuch less developed than that for large-scale <strong>fisheries</strong>, <strong>and</strong> transferability <strong>of</strong>management approaches from <strong>the</strong> latter to <strong>the</strong> former is highly questionablegiven <strong>the</strong> major differences both in <strong>the</strong> characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>and</strong> in<strong>the</strong>ir importance to fishing households. Even if <strong>the</strong>se tools were transferable, animportant management limitation – <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> human <strong>and</strong> economic resources –remains a key challenge (FAO, 2000; Salas et al., 2007; Mahon et al., 2008).

10<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>These problems are discussed in a number <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> chapters, <strong>and</strong> a summary<strong>of</strong> trends in adoption <strong>and</strong> use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> various assessment <strong>and</strong> management toolsis presented in Chapter 14. This compilation <strong>of</strong> information serves three goals.First, an overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> in terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir biological, social <strong>and</strong> economicassessment provides insights for management purposes. Second, <strong>the</strong> documentaims to identify research gaps in coastal <strong>fisheries</strong>, to provide guidance on prioritiesfor research <strong>the</strong>mes, approaches <strong>and</strong> tools. In this regard, it becomes clear thatto achieve a sufficient underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> fishery complexities, an emphasis onmultidisciplinary research – incorporating <strong>the</strong> bio-ecological <strong>and</strong> socio-economicprocesses <strong>of</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> – is critical. Third, we see from this analysis that from amanagement perspective, <strong>the</strong> complex characteristics <strong>of</strong> coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> dem<strong>and</strong>a shift away from conventional approaches, towards a system that enables localorganizations to adapt to both <strong>the</strong> current context inside <strong>the</strong> LAC region <strong>and</strong> toglobal trends.REFERENCESAgüero M. 1992. La pesca artesanal en América <strong>Latin</strong>a: una visión panorámica. InContribuciones para el estudio de la pesca artesanal en América <strong>Latin</strong>a. Editedby M. Agüero. ICLARM Conference Proceedings Contribution No. 835, ManilaPhilippines. pp. 1–27.Agüero M. & Claverí M. 2007. Capacidad de pesca y manejo pesquero en América<strong>Latin</strong>a: una síntesis de estudios de caso. In Capacidad de pesca y manejo pesqueroen América <strong>Latin</strong>a y el Caribe. Edited by M. Agüero. FAO, Doc. Téc. Pesca, 461.Roma. FAO. pp. 61–72.Beltran C. 2005. Evaluación de la pesca de pequeña escala y aspectos de ordenaciónen cinco países seleccionados de América <strong>Latin</strong>a: El Salvador, Costa Rica, Panamá,Colombia y Ecuador. Períodos, 1997–2005. FAO Circular de Pesca No 957/2, FAONaciones Unidas, Roma.Bené C., Macfayden G. & Allison E.H. 2007. Increasing <strong>the</strong> contribution <strong>of</strong> smallscale<strong>fisheries</strong> to poverty alleviation <strong>and</strong> food security. FAO Fisheries TechnicalPaper. No. 481. Rome, FAO.Castilla J.C. & Defeo O. 2005. Paradigm shifts needed for world <strong>fisheries</strong>. Science,309: 1324–1325.Chakalall B., Mahon R., McConney P., Nurse L. & Oderson D. 2007. Governance<strong>of</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r living marine resources in <strong>the</strong> Wider <strong>Caribbean</strong>. Fish. Res., 87:92–99.Charles A. 2001. Sustainable Fishery Systems. Oxford, UK. Blackwell Science.Cochrane K.L. 1999. Complexity in <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>and</strong> limitations in <strong>the</strong> increasingcomplexity <strong>of</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> management. ICES J. Mar. Sci., 56: 917–926.Ehrhardt N.M. 2007 Evaluación y administración de la capacidad de pesca deacuerdo a criterios de pesca sustentable aplicable a especies anuales: las pesqueríasde camarón en Guatemala y Nicaragua como un ejemplo. In Capacidad de pesca ymanejo pesquero en América <strong>Latin</strong>a y el Caribe. Edited by M. Agüero. FAO, Doc.Téc. Pesca, 461. Roma, FAO. pp. 117–150.

12<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>Soutar A. & Isaacs J.D. 1974. Abundance <strong>of</strong> pelagic fish during <strong>the</strong> 19 th <strong>and</strong> 20 thcenturies as recorded in anaerobic sediment <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> Californias. Fish. Bull. (US), 72:257–273.Spalding M. & Kramer P. 2004. The <strong>Caribbean</strong>. In Defying Ocean’s End. An agendafor action. Edited by L. Glover <strong>and</strong> S.A. Earle. Washington DC, USA, Isl<strong>and</strong> Press.pp. 7–42.Staples D., Satia B. & Gardiner P.R. 2004. A research agenda for small-scale <strong>fisheries</strong>.FAO/RAP Publication/FIPL/C10009. Rome, FAO.Swan J. & Gréboval D. 2004. Report <strong>and</strong> Documentation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> InternationalWorkshop on <strong>the</strong> Implementation <strong>of</strong> International Fisheries Instruments <strong>and</strong>Factors <strong>of</strong> Unsustainability <strong>and</strong> Overexploitation in Fisheries. Mauritius, 3–7February 2003. FAO Fisheries Report, No. 700, Rome, FAO.Vasconcellos M., Kolikoski D.C., Haimovici M. & Abdallah P.R. 2007. Capacidadexcesiva del esfuerzo pesquero en el sistema estuarino-costero del sur de Brasil:efectos y perspectivas para su gestión. In Capacidad de pesca y manejo pesqueroen América <strong>Latin</strong>a y el Caribe. Edited by M. Agüero. FAO, Doc. Téc. Pesca 461.Roma, FAO. pp. 275–308.World Bank. 2004. Saving fish <strong>and</strong> fishers. Toward sustainable <strong>and</strong> equitablegovernance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> global fishing sector. The World Bank. Agriculture <strong>and</strong> RuralDevelopment Department. Report No. 29090_GLB.Wosnitza-Mendo C., Mendo J. & Guevara-Carrasco R. 2007. Políticas de gestiónpara la reducción excesiva de esfuerzo pesquero en Peru: el caso de la pesquería dela merluza. In Capacidad de pesca y manejo pesquero en América <strong>Latin</strong>a y el Caribe.Edited by M. Agüero. FAO, Doc. Téc. Pesca 461. Roma, FAO. pp. 343–371.Zwanenberg K.C.T., Bowen D., Bundy A., Drinkwater K., Frank K., O’Boyle R.,Sameoto D. & Sinclair M. 2002. Decadal changes in <strong>the</strong> Scotian shelf largemarine ecosystem. In Large Marine Ecosystems <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> North Atlantic. Edited byK. Sherman <strong>and</strong> H.R. Skjoldal. Elsevier Science, B.V. pp. 105–150.

132. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> ArgentinaInés Elías * , Claudia Carozza, Edgardo E. Di Giácomo, Miguel S. Isla, J. M. (Lobo)Orensanz, Ana María Parma, Raúl C. Pereiro, M. Raquel Perier, RicardoG. Perrotta, María E. Ré <strong>and</strong> Claudio RuarteElías, I., Carozza, C., Di Giácomo, E.E., Isla, M.S., Orensanz, J.M. (Lobo), Parma, A.M.,Pereiro, R.C., Perier, M.R., Perrotta, R.G., Ré, M.E. <strong>and</strong> Ruarte, C. 2011. <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong><strong>of</strong> Argentina. In S. Salas, R. Chuenpagdee, A. Charles <strong>and</strong> J.C. Seijo (eds). <strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>. FAO Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Aquaculture Technical Paper. No. 544.Rome, FAO. pp. 13–48.1. Introduction 142. Description <strong>of</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>and</strong> fishing activities 162.1 <strong>Coastal</strong> shellfish ga<strong>the</strong>ring 212.2 Beach seining 262.3 Gill <strong>and</strong> tangle nets deployed in <strong>the</strong> intertidal zone 262.4 Bottom tangle nets <strong>and</strong> tide-intersecting nets deployed from boats 272.5 Beam trawling 282.6 Commercial diving 292.7 Bottom longlining 302.8 The ‘lampara’ (h<strong>and</strong>-thrown seine) fishery 312.9 Trap <strong>fisheries</strong> 313. Fishers <strong>and</strong> socio-economic aspects 313.1 Description <strong>of</strong> fishers 313.2 Social <strong>and</strong> economical aspects 334. Community organization <strong>and</strong> interactions with o<strong>the</strong>r sectors 354.1 Community organization 354.2 Interactions between fishers <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r sectors 364.3 Integrated management <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> coastal zone <strong>and</strong> marine conservation 375. Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> 386. Fishery management <strong>and</strong> planning 397. Research <strong>and</strong> education 41Acknowledgements 42References 43* Contact information: Centro Nacional Patagónico (CENPAT-CONICET). Puerto Madryn,Chubut, Argentina. E-mail: elias@cenpat.edu.ar

14<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>1. INTRODUCTIONOver centuries <strong>the</strong> coasts <strong>of</strong> Argentina were inhabited by aboriginal peoples that,mostly towards <strong>the</strong> south, harvested marine resources. The archaeological recordshows evidence <strong>of</strong> consumption <strong>of</strong> mammals, amphibians, molluscs <strong>and</strong> fishesalong Patagonian shores. The ga<strong>the</strong>ring methods <strong>and</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se earlyfishers were not, however, incorporated by <strong>the</strong> colonial society, contrary to whatwas <strong>the</strong> case in Peru <strong>and</strong> Chile, which became leading countries with regard toartisanal fishing activities. It is perhaps because <strong>of</strong> this, toge<strong>the</strong>r with prevalentpolicies that prioritized agriculture <strong>and</strong> husb<strong>and</strong>ry, that fishing <strong>and</strong> fishers areperceived as exotic (Mateo Oviedo, 2003).Over recent decades, because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> employment opportunities intraditional sectors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> economy <strong>and</strong> in industrial <strong>fisheries</strong>, as well as populationgrowth in coastal areas, groups <strong>of</strong> artisanal fishers have sprouted in many areaswhere <strong>the</strong>y did not operate before. Small-scale fishing is becoming a permanentway <strong>of</strong> life for many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se new fishers.The first difficulty encountered while trying to describe <strong>and</strong> analyse <strong>the</strong>artisanal sector is its definition. A comparative look at how ‘artisanal <strong>fisheries</strong>’ aredefined indicates that recurrent criteria are: size <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> boats, gross tonnage, fishinggear <strong>and</strong> socio-economic considerations. Fishing operations that are considered‘artisanal’ in some countries do not qualify as such in o<strong>the</strong>rs. The same happenseven within Argentina, a country with an extended coastline <strong>and</strong> divergentregional realities.An economical anthropology perspective singles out additional factors tha<strong>the</strong>lp <strong>the</strong> characterization: property <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> means <strong>of</strong> production, production <strong>of</strong>merch<strong>and</strong>ise, management <strong>of</strong> economical activities, division <strong>of</strong> labour, degree <strong>of</strong>association, etc. (García-Allut, 2002).As used in Argentina, <strong>the</strong> term ‘artisanal’ encompasses a wide spectrum, fromcoastal ga<strong>the</strong>ring to inshore fleets. This chapter deals with coastal ga<strong>the</strong>rers,beach seiners <strong>and</strong> boats <strong>of</strong> variable dimensions ranging, according to García-Allut(2002), from ‘strictly artisanal’ to ‘semi-industrial’.Argentina, located at <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>America</strong>s, has one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largestshelf areas in <strong>the</strong> world (about 1 million km 2 ) <strong>and</strong> an extended coastline (4 000 km).The eastern <strong>and</strong> western boundaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shelf are, respectively, <strong>the</strong> continentalslope <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> coastline (Figure 1). The nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>and</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn boundaries arejurisdictional. Resources harvested by small-scale <strong>and</strong> artisanal fishers are sharedwith o<strong>the</strong>r jurisdictions: to <strong>the</strong> north with Uruguay in <strong>the</strong> Argentine-UruguayanCommon Fishing Zone between <strong>the</strong> two countries (ZCPAU), <strong>and</strong> to <strong>the</strong> southwith Chile.These settings imply that, geographically, Argentina is a maritime countryyet, because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> way its population is distributed, it is effectively a continentalcountry. Four provinces out <strong>of</strong> five with a maritime border (<strong>the</strong> exception beingBuenos Aires) conform <strong>the</strong> Patagonian region, where coastal urban settlements arefar apart from each o<strong>the</strong>r (Figure 1). This configuration highlights <strong>the</strong> significance<strong>of</strong> gulfs, bays <strong>and</strong> estuaries in <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> coastal activities.

<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Argentina 15FIGURE 1The main fishing harbours on <strong>the</strong> continental coast <strong>of</strong> Argentina(indicated by black dots)Water masses above <strong>the</strong> continental shelf are characterized by <strong>the</strong> mixingbetween water <strong>of</strong> subantarctic origin, flowing in mostly between <strong>the</strong>Falkl<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s/Islas Malvinas <strong>and</strong> Tierra del Fuego, <strong>and</strong> waters diluted bycontinental run<strong>of</strong>f <strong>and</strong> originating in <strong>the</strong> Magellan Strait. These water masses <strong>of</strong>mixed origin are altered by heat interchange with <strong>the</strong> atmosphere (Piola <strong>and</strong> Rivas,1997).Balech (1986) showed that by late September or October <strong>the</strong> water <strong>of</strong>nor<strong>the</strong>rn origin flows south, <strong>of</strong>f Buenos Aires Province <strong>and</strong> westward <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Falkl<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s/Islas Malvinas Current, reaching as far south as Valdés Peninsula(42º south latitude) by mid- or late-December. This phenomenon is very importantbecause <strong>of</strong> its effect on coastal <strong>fisheries</strong> (Balech, 1986; Perrotta et al., 2001).In <strong>the</strong> Patagonian region, between 42º <strong>and</strong> 47º south latitude, a series <strong>of</strong>frontal systems <strong>of</strong> variable intensity develop towards late spring (late November)

16<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Latin</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong><strong>and</strong> during <strong>the</strong> summer (December–February), favouring <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong>spawning grounds with good conditions for <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eggs <strong>and</strong>larvae <strong>of</strong> several fish species (Sánchez <strong>and</strong> Ciechomski, 1995; Ehrlich et al., 2000).The nor<strong>the</strong>rn end <strong>of</strong> Patagonia (41º to 43º south latitude) has three gulfs thatharbour fishing activities <strong>of</strong> regional significance: San Matías (shared by <strong>the</strong> RíoNegro <strong>and</strong> Chubut Provinces) <strong>and</strong> San José <strong>and</strong> Nuevo (Chubut Province). Thethree are shaped as extensive basins deeper than <strong>the</strong> adjacent shelf (Rivas <strong>and</strong> Beier,1990). Waters are more saline than in <strong>the</strong> adjacent shelf, <strong>and</strong> temperature variationis comparatively high. San José Gulf is <strong>the</strong> smallest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se three <strong>and</strong> its highproductivity was highlighted by Charpy-Roubaud et al. (1978).2. DESCRIPTION OF FISHERIES AND FISHING ACTIVITIESArgentina is, by its Constitution, a representative <strong>and</strong> federal republic formed by23 provinces <strong>and</strong> a federal district, all autonomous states endowed with political<strong>and</strong> administrative powers. The Argentina Constitution establishes executive,legislative <strong>and</strong> judiciary branches <strong>and</strong> does not contain specific language relative to<strong>fisheries</strong> or maritime jurisdictions, but assigns to <strong>the</strong> legislature <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> executiveauthority regarding treaties, navigation, customs <strong>and</strong> ports.Several agencies in <strong>the</strong> federal administration have a say in fishing-relatedsubjects: <strong>the</strong> National Service <strong>of</strong> Agricultural Quality <strong>and</strong> Health (SENASA,within <strong>the</strong> Ministry <strong>of</strong> Economy <strong>and</strong> Production) certifies processing plants; <strong>the</strong>Undersecretary <strong>of</strong> Fisheries (within <strong>the</strong> Secretary <strong>of</strong> Agriculture, Husb<strong>and</strong>ry <strong>and</strong>Fishing) elaborates <strong>and</strong> coordinates <strong>the</strong> execution <strong>of</strong> policies for <strong>the</strong> promotion <strong>and</strong>regulation <strong>of</strong> fishing activities; <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prefectura Naval (<strong>the</strong> coast guard) keepstrack <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vessel registry, cares for <strong>the</strong> security <strong>of</strong> navigation, grants credentialsto crews (deckh<strong>and</strong>s, skippers, divers, etc.) <strong>and</strong> patrols <strong>the</strong> coastal zone.The Federal Fishing Act <strong>of</strong> 1998 (Ley Federal de Pesca, No. 24922) statesthat living aquatic resources from lakes <strong>and</strong> rivers, gulfs <strong>and</strong> inshore areas (from<strong>the</strong> coastline to 12 nautical miles <strong>of</strong>fshore) are under provincial jurisdiction.Outside this boundary, waters within <strong>the</strong> exclusive economic zone (EEZ) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>continental shelf are in <strong>the</strong> federal domain (Article 4). The Act establishes that<strong>the</strong> application authority at <strong>the</strong> national level is <strong>the</strong> Undersecretary <strong>of</strong> Fisheries,<strong>and</strong> that a Federal Fisheries Council defines national fishing policy <strong>and</strong> researchpriorities. The Council is integrated by a representative from each maritimeprovince, <strong>the</strong> Undersecretary <strong>of</strong> Fisheries, <strong>and</strong> delegates from <strong>the</strong> Undersecretary<strong>of</strong> Natural Resources <strong>and</strong> Sustainable Development, <strong>the</strong> Ministry <strong>of</strong> ForeignAffairs <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> federal executive.In addition, Act 20645 <strong>of</strong> 1974 establishes a common fishing zone withUruguay. Regulations adopted for coastal resources <strong>and</strong> some pelagic resourceswithin this zone must be discussed in <strong>the</strong> ambit <strong>of</strong> two bi-national commissions,<strong>the</strong> Joint Technical Commission for <strong>the</strong> Maritime Front (CTMFM) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>Managing Commission for <strong>the</strong> La Plata River (CARP).

<strong>Coastal</strong> <strong>fisheries</strong> <strong>of</strong> Argentina 17At <strong>the</strong> regional level, coastal resources are managed by <strong>the</strong> provinces through<strong>the</strong>ir respective agencies (secretaries, undersecretaries, etc.), which <strong>of</strong>ten haveoverlapping m<strong>and</strong>ates, both with each o<strong>the</strong>r within provincial administrations<strong>and</strong> with federal agencies. Governmental structures are usually organized onfunctional grounds with little horizontal linkage (e.g. between agencies dealingwith <strong>fisheries</strong>, <strong>the</strong> environment, health, etc.).The agency in charge <strong>of</strong> planning <strong>and</strong> execution <strong>of</strong> scientific <strong>and</strong> technicalprogrammes at <strong>the</strong> federal level is <strong>the</strong> National Institute for Fisheries Research<strong>and</strong> Development (INIDEP), which depends on <strong>the</strong> Secretary <strong>of</strong> Agriculture,Husb<strong>and</strong>ry, Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Food (Act 21673 <strong>of</strong> 1977). Its mission is to plan,execute <strong>and</strong> develop research projects, including surveys, assessments <strong>and</strong>development, aquaculture technology, fishing gear, technological processes <strong>and</strong><strong>fisheries</strong> economics, according to guidelines <strong>and</strong> priorities defined by <strong>the</strong>application authority.Scientific <strong>and</strong> technical support for management at <strong>the</strong> regional level isprovided by o<strong>the</strong>r research centres, which interact to variable degrees withprovincial <strong>fisheries</strong> administrations <strong>and</strong> with INIDEP. Some examples are: <strong>the</strong>National University <strong>of</strong> Mar del Plata in Buenos Aires Province; <strong>the</strong> Institute<strong>of</strong> Marine <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Biology ‘Almirante Storni’ in Río Negro Province; <strong>the</strong>National Patagonic Center (CENPAT), a regional branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Councilfor Scientific <strong>and</strong> Technical Research (CONICET) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> National University <strong>of</strong>Patagonia in Chubut; a technical school for fishers (FOCAPEM) in Santa Cruz;<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Austral Center for Scientific Research (CADIC, as CENPAT, a branch <strong>of</strong>CONICET) in Tierra del Fuego.Artisanal fishing units, as defined here, include coastal ga<strong>the</strong>rers, commercialdivers, beach seiners <strong>and</strong> small boats (usually less than 10 m long) deployinga variety <strong>of</strong> gear types (gill <strong>and</strong> tangle nets, longlines, hook-<strong>and</strong>-line, traps).Inshore fleets include two o<strong>the</strong>r size-brackets <strong>of</strong> vessels, shorter <strong>and</strong> longer than18 m (Table 1). Small inshore vessels (10–18 m) are usually known as <strong>the</strong> rada/ría (roughly meaning coves <strong>and</strong> estuaries) fleet, which rarely operate beyond <strong>the</strong>50 m isobath. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se boats have wooden hulls, are relatively old (50 yearson average), <strong>and</strong> have minimal navigation <strong>and</strong> detection equipment. Holdingcapacity ranges from 4 to 14 tonnes <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y have no cold-storage capacity. Crewscan be up to 10 fishers. This fleet operates from most Argentine fishing harbours,with its epicentre in Mar del Plata, both in terms <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong>ings <strong>and</strong> number <strong>of</strong> boats(Lasta et al., 2001). It is busy all year round <strong>and</strong> is socially dynamic. Larger vessels(longer than 18 m) operate fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong>fshore during <strong>the</strong> autumn, targeting hake.According to <strong>the</strong> typology proposed by García-Allut (2002), <strong>the</strong> rada/ría fleetfalls in <strong>the</strong> semi-industrial category, <strong>and</strong> is thus included in this overview. Largervessels operating in <strong>the</strong> inshore fishery are not. In addition, Table 2 summarizes<strong>the</strong> fishing activities discussed in this section.