Mycteria cinerea - BirdBase

Mycteria cinerea - BirdBase

Mycteria cinerea - BirdBase

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

MILKY STORK<br />

<strong>Mycteria</strong> <strong>cinerea</strong><br />

Critical —<br />

Endangered —<br />

Vulnerable A2c,d; C1<br />

This stork has a small, declining population owing to loss of coastal habitat, hunting and trade.<br />

These factors are predicted to cause rapid declines in the near future. It therefore qualifies as<br />

Vulnerable.<br />

DISTRIBUTION The Milky Stork is widely but very patchily distributed in South-East<br />

Asia. It is known from Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Peninsular Malaysia and Indonesia,<br />

with an unconfirmed record from Singapore (see Remarks 1).<br />

■ THAILAND The species is clearly at the edge of its range in Thailand and the very few<br />

records represent either vagrants or escaped birds; if it ever bred in the country it is now<br />

presumed no longer to do so (Treesucon and Round 1990). Records are from: north of Laem<br />

Phak Bia, Phetchaburi, 1–3 in a flock of c.100 Painted Storks <strong>Mycteria</strong> leucocephala,<br />

September and October 1998 (P. Charoenjai, J. Visetchinda and S. Supparativikorn per<br />

P. D. Round in litt. 1998, Bird Cons. Soc. Thailand Bull. 16, 10 [1999]: 18–19, Oriental Bird<br />

Club Bull. 30 [1999]: 52–56); Satul, one adult, August 1935 (Gibson-Hill 1949b, Medway and<br />

Wells 1976; also Morioka and Yang 1990).<br />

A bird at Wat Asokaram, Bang Poo, Samut Prakan, January 1994 (seen by Suradech<br />

Wongsinlang) was said to have been present from October 1993 and was thought to be an<br />

escape owing to its tameness (P. D. Round in litt. 1999).<br />

■ CAMBODIA Apart from one record in Banteay Meanchay province, this species<br />

is apparently restricted to the immediate vicinity of Tonle Sap lake and coastal Kompong<br />

Som (=Sihanoukville) province (Sun Hean in litt. 1997). Records are from: Ang Trapeang<br />

Thmor Reserve, one June 2000 (P. Davidson verbally 2000); between Sisophon and Siem<br />

Reap, 1960s (Thomas 1964); Siem Reap, December 1927 (two specimens in BMNH; also<br />

Thomas 1964); Prek Da, 15, April 1994 (Mundkur et al. 1995a, Oriental Bird Club Bull. 20<br />

[1994]: 55–61), 20–60 pairs reported by locals in the last few years (Parr et al. 1996), including<br />

two singletons in May and June 1998 (Goes et al. 1998b); Prek Toal, Battambang, the only<br />

confirmed breeding site in Cambodia, 15, 1994 (Mundkur et al. 1995a), c.15 pairs, 1996<br />

(Parr et al. 1996), up to six, February and March 1996, with presence of chicks in villages<br />

confirming local breeding (Parr et al. 1996), three, 1997 (Ear-Dupuy et al. 1998), four plus<br />

a distant group of 31, April 1999 (F. Goes and C. M. Poole in litt. 1999), three, April 2000<br />

(P. Davidson in litt. 2000), and nearby at the Stoeng Sangke (Sangke river), one, July 1998<br />

(Goes et al. 1998b) and Boeng Rohal, three, March–April 1997 (Ear-Dupuy et al. 1998);<br />

Prek Peach Kantoeli (Prek Peach Kantiel), one, July 1998 (Goes et al. 1998b); Kampong<br />

Chhnang, at Chhunuk Tru, one, May 1993 (Carr 1993); Tnal Krabei, Prek Kaoh Pao<br />

estuary, 5 km south of Koh Kong town, “some”, April 1944 (Engelbach 1952); Stoeng Kampong<br />

Smach, Kampong Som (=Sihanoukville), one, April 1994 (Mundkur et al. 1995a, Oriental<br />

Bird Club Bull. 20 [1994]: 55–61), and one near Prek Kampong Smach with 50 Painted<br />

Storks, December 1995 (J. C. Eames in litt. 2000); Kampong Som (=Sihanoukville), one,<br />

February 1999 (D. Judell verbally 1999), eight, including three immatures, April 1999<br />

(J. Smith and C. M. Poole in litt. 1999); Ream National Park, seven, March 1996 (J. W. K.<br />

Parr in litt. 1998), eight (including three immatures), April 1999 (Cambodia Bird News 2<br />

[1999]: 38–39, 3: 39–43).<br />

169

Threatened birds of Asia<br />

■ VIETNAM Despite repeated recent reports (including intimations of breeding), none is<br />

acceptable (Eames and Tordoff in prep.; see Remarks 2). The only record is from: Bac Lieu,<br />

where two captive birds at Ho Chi Minh city (=Saigon) Zoo had apparently been captured<br />

(Delacour and Jabouille 1931), although there is no further report from the province (Scott<br />

1989).<br />

■ MALAYSIA An isolated resident population of this species survives on the north-east<br />

coast of Peninsular Malaysia (Perak); there have also been a few records from the southwest<br />

coast (Johor), possibly of wanderers from the nearby Sumatran population to the west<br />

rather than the more distant Perak population (Hawkins and Howes 1986, Wells 1999; but<br />

see Remarks 1). Confirmed records are from: Kuala Kedah, late November 1907 (Robinson<br />

and Kloss 1910–1911, Robinson and Chasen 1936); Sungai Burong (Sungai Burung), Kuala<br />

Kurau, Perak, October 1984 (Swennen and Marteijn 1987, Wells 1990b); Matang Mangrove<br />

Forest Reserve, Perak, including Kuala Gula, 42 in 1975, 79 in August 1983 (Parish and<br />

Wells 1985), 31 in 1984 (Swennen and Marteijn 1985), and many records until the present,<br />

also slightly further south at Pulau Kelumpang, Kuala Kurau, 74, August 1983 (Wells 1990a),<br />

maximum of 101 in October 1984 (Swennen and Marteijn 1987, Wells 1990b), and 29 nests<br />

in 1989 (Siti Hawa Yatim 1990, Wells 1999), at Pulau Terong, 40, January–February 1986<br />

(Hawkins and Silvius 1986), to the south of Kuala Larut, 36 at a pool in mangroves, August<br />

1983 (Parish and Wells 1985, Wells 1990a), and at unspecified localities in the forest reserve,<br />

57 adults, March 1989 (Enggang 2, 4 [1989]), and 42 in September 1995 (A. C. Sebastian in<br />

litt. 1999); Pulau Ketam, Kelang estuary, Selangor, “up to four pairs” breeding, 1933–1935<br />

(Madoc ms, Madoc 1936 in Wells 1999), including two nests in August 1935 (Robinson and<br />

Chasen 1936), subsequently disappearing along with the heronry (DWNPPM 1987); Sungai<br />

Kinchin, Pahang, July 1989 (Wells 1990d); on the coast of Melaka (Malacca), mid-nineteenth<br />

century (Gibson-Hill 1949 in Wells 1999); Benut Forest Reserve, Johor, apparently in 1950s<br />

(Wells 1999), two at Kuala Sanglang, February 1985, one on the foreshore at Kuala Benut,<br />

March 1986 (Hawkins and Howes 1986, Wells 1990c).<br />

■ INDONESIA Highest numbers are recorded from Sumatra and Java where the species<br />

breeds, with lesser numbers from Sulawesi (breeding likely), Buton and Sumbawa. The global<br />

stronghold of the species is Sumatra, where it is primarily distributed along the coasts in the<br />

coastal swamps of Aceh, North, Jambi and Lampung provinces, with breeding recorded in<br />

the latter two of these (van Marle and Voous 1988). Records for the country are from:<br />

Sumatra ■ Aceh large numbers on a creek near Banda Aceh, February 1873 (Hume 1873b);<br />

Lhokseumawe, 1970, 1981–1982 and 1985 (Burton 1985 in van Marle and Voous 1988);<br />

■ North Sumatra Ramunia, Serdang, June 1915 (male in ZMA, de Beaufort and de Bussy<br />

1919); Perbaungan, December 1920 (male in RMNH); Serbadjadi, and elsewhere in Deli,<br />

1913 and 1916 (specimens in ZMA, RMNH); between Bukittinggi and Sipirok, one, October<br />

1993 (J. N. Dymond in litt. 1999); ■ West Sumatra Bukittinggi (=Fort de Kock), 900 m,<br />

undated (Kloss 1931); Danau Singkarak, 400 m, February 1977 (van Marle and Voous 1988);<br />

Solok, undated (specimen in AMNH); Lunang, West Sumatra, October 1990 (Holmes 1996);<br />

■ Riau Ollak Tanding, Sindang, October 1881 (female in BMNH); Pulau Halang, March<br />

1981 (van Marle and Voous 1988); Bagansiapiapi region, with strong evidence of breeding in<br />

the Kubu area, perhaps also on Bengkalis, August 1990 (Holmes 1996); Kampar estuary, six,<br />

February 1999 (S. J. M. Blaber in litt. 1999); concentrations of feeding birds at coastal<br />

promontories such as Tanjung Datuk and Tanjung Bakung, undated (Silvius 1988);<br />

Kualacenako (Kuala Cinaku), on the border with Jambi, November 1992 (Holmes 1996),<br />

Kateman (not mapped), 1930 (Morioka and Yang 1996); ■ Jambi Kuala Betara, Hutan Bakan<br />

Pantai Timor Nature Reserve (74 active nests in late July 1985), west side of Sungai Betara,<br />

mid-1980s (Danielsen and Skov 1985, 1987), but colony gone by 1989 (Danielsen et al. 1991b);<br />

Tanjung Jabung, undated (Silvius 1988); Sungai Batang Hari, c.50 km inland, 1980s (Verheugt<br />

170

<strong>Mycteria</strong> <strong>cinerea</strong><br />

1987); Berbak National Park at Sungei Lokan, 126 in September 1986 (A. Elliott per T. P.<br />

Inskipp in litt. 1997), and at Sungei Simpang Gajah, one, September 1986 (A. Elliott per T. P.<br />

Inskipp in litt. 1997); ■ South Sumatra entire coastline, including Banyuasin peninsula, major<br />

colony, September 1988 (Danielsen et al. 1991a; see Population); Tanjung Selokan, major<br />

colony, September 1988 (Danielsen et al. 1991a; see Population); Padang Sugihan Wildlife<br />

Reserve, regularly August–October 1984 and May–June 1985 (but with no records between<br />

these dates), including a bird in breeding plumage, May (Nash and Nash 1985); Tanjung<br />

Koyan, major colony, September 1988 (Danielsen et al. 1991a; see Population); ■ Lampung<br />

near Menggala, 1993–1994 (Holmes and Noor 1995); Way Kambas National Park, resident<br />

(Wind et al. 1979), with an apparent breeding colony of 200–230 found 6 km south of Pos<br />

Pedemaran, June 1989, and many records from within the area (Parrott and Andrew 1996);<br />

Telukbetung, undated (specimen in RMNH); (untraced) estuaries of the Siput river and Jentolo<br />

river, large numbers in 1980s (Verheugt 1987);<br />

Java ■ West Java Ujung Kulon National Park, 1940s (Hoogerwerf 1948a); Pulau Dua,<br />

where formerly breeding (Hoogerwerf 1947a, 1948a) and last recorded doing so in 1975, but<br />

now a regular visitor, often roosting there (Milton and Marhadi 1985); Serang, flock of 49<br />

flying east, September 1984 (Allport and Wilson 1986); Tangerang, north coast, July 1935<br />

(Hoogerwerf 1936a); Pulau Rambut Wildlife Reserve, Jakarta Bay, since 1974, and including<br />

January 1987 (Lambert and Erftemeijer 1989), 42 adults, five fledged young and five active<br />

nests, June 1989 (Wilkinson et al. 1991a); Jakarta (=Batavia) and environs, until 1930s<br />

(Hoogerwerf and Siccama 1937–1938, Hoogerwerf 1948a, specimen in MCZ), and more<br />

recently at Ancol beach, June 1989 (Wilkinson et al. 1991a), regular at Muara Angke, undated<br />

(Bartels 1915–1930), and occurring there recently including August 1993 (N. Bostock in litt.<br />

1999), August 1994 (Tobias and Phelps 1994), and in roadside pools near Soekarno-Hatta<br />

airport, including several in September 1996 (JAT), but decreasing at this site as it becomes<br />

more disturbed and developed (B. F. King verbally 1998); Muara Gembong, September 1915<br />

and April 1917 (two females in RMNH); Muara Wetan, August 1908 and April 1914 (two<br />

specimens in RMNH), October 1922 (two juveniles in RMNH); Citarum delta (this general<br />

area includes other sites such as Muara Gembong and Balubuk), seasonally very common<br />

and breeding, undated (Bartels 1915–1930), including at Muara Bungin, 1907–1923 (five<br />

specimens in RMNH); Balubuk (Muara Blubuk), July 1919 (one immature and one pullus in<br />

RMNH) and May 1922 (male in RMNH); Rawa Gempol, Krawang, October 1908 (van Oort<br />

1910; also two females in AMNH); Tanjung Sedari (Sedari delta), seasonal in occurrence<br />

(usually in the “east monsoon”), undated (Bartels 1915–1930); Indramayu, April 1925 (male<br />

in RMNH), at the Bungko estuary, November 1990 (Indrawan et al. 1993b); Cirebon<br />

(Cheribon), October 1925 (male in RMNH); ■ Central Java Segara Anakan, east of<br />

Pangandaran, where recorded in early 1980s (Verheugt 1987), a non-breeding area for 160–<br />

180 birds, with up to 20, mid-1989 (Erftemeijer et al. 1988, Lewis et al. 1989), “small” numbers,<br />

July 1991 (Heath 1991); Nusa Kambangan, 25 birds foraging near Klacis, August 1998<br />

(V. Nijman in litt. 2000); Tegal, February 1910 (male in RMNH); ■ East Java Surabaya, one<br />

immature shot on a nearby pond, undated (Bartels 1915–1930); Baluran National Park,<br />

“small” numbers, July 1991 (Heath 1991);<br />

Madura Sumenep, 170, March 1996 (Oriental Bird Club Bull. 24 [1996]: 59–65);<br />

Bali an “irregular visitor” (Verheugt 1987), including one passing east over Gilimanuk,<br />

October 1982 (Ash 1984, NJC; see Migration);<br />

Sumbawa unspecified locality (Verheugt 1987), “west coast”, May 1988 (Silvius and<br />

Verheugt 1989) and Taliwang, December 1989 (Gibbs 1990), where apparently seen the<br />

previous year;<br />

Sulawesi ■ North Sulawesi small lake c.10 km east of Panua Reserve (near Marisa),<br />

Kecamatan Paguat, Desa Sale Lama, flock of 51, all in adult, mostly non-breeding plumage,<br />

December 1997, but none in August 1999 (Bishop in press); Marisa, 10–15 birds, February<br />

171

Threatened birds of Asia<br />

1979 (Watling 1983b); Tanjung Panjang, a group of c.15, December 1978 (J. R. MacKinnon<br />

in Escott and Holmes 1980; also White and Bruce 1986); ■ Central Sulawesi Kolumbi, Roraya<br />

district, August 1978 (Escott and Holmes 1980; also White and Bruce 1986); ■ South<br />

Sulawesi Palopo and adjacent shoreline, undated (Holmes and Wood 1980 in White and<br />

Bruce 1986), March/April 1986 (Uttley 1987); near Polewali, undated (Escott and Holmes<br />

1980); Danau Tempe, two adults and one juvenile, January 1990 (Baltzer 1990); Palima in the<br />

Cendrenai (Cenrana) delta, March 1986, at least 33 birds including four immatures, the first<br />

evidence of possible breeding on the island (Uttley 1987), late 1989 (Baltzer 1990); Maros,<br />

five, March 1977 (Escott and Holmes 1980); Makassar (= Ujung Pandang), undated records<br />

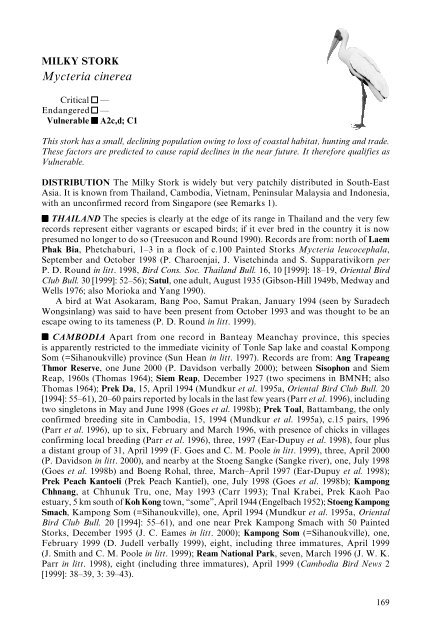

THAILAND<br />

1<br />

4 3<br />

5<br />

CAMBODIA<br />

6 9<br />

7 10<br />

8 12 11<br />

13 14<br />

VIETNAM<br />

SUMATRA<br />

(INDONESIA)<br />

22<br />

23<br />

I N D I A N<br />

O C E A N<br />

2<br />

15<br />

S O U T H<br />

C H I N A<br />

S E A<br />

MALAYSIA<br />

16<br />

17<br />

24<br />

25 18<br />

26 20 19<br />

33<br />

21<br />

34<br />

27<br />

35<br />

28 38 36<br />

29<br />

37<br />

30 39 40<br />

31 4142<br />

55<br />

43 44 56<br />

32<br />

57<br />

45 46 58<br />

47 59<br />

48 60<br />

54<br />

49 51 61 62<br />

50 52 66<br />

53 63<br />

65<br />

67<br />

64<br />

JAVA<br />

(INDONESIA)<br />

69<br />

70<br />

68<br />

71<br />

SULAWESI<br />

(INDONESIA)<br />

73<br />

74 72 75<br />

76<br />

77<br />

84<br />

85 83<br />

80 78<br />

79<br />

81 86<br />

82 87<br />

The distribution of Milky Stork <strong>Mycteria</strong> <strong>cinerea</strong>: (1) Laem Phak Bia; (2) Satul; (3) Ang Trapeang Thmor<br />

Reserve; (4) Sisophon; (5) Siem Reap; (6) Prek Da; (7) Prek Toal; (8) Prek Peach Kantoeli; (9) Kampong Chhnang;<br />

(10) Koh Kong; (11) Stoeng Kampong Smach; (12) Kampong Som; (13) Ream National Park; (14) Bac Lieu;<br />

(15) Kuala Kedah; (16) Sungai Burong; (17) Matang Mangrove Forest Reserve; (18) Pulau Ketam; (19) Sungai<br />

Kinchin; (20) Melaka; (21) Benut Forest Reserve; (22) Banda Aceh; (23) Lhokseumawe; (24) Ramunia;<br />

(25) Perbaungan; (26) Serbajadi; (27) Sipirok; (28) Bukittinggi; (29) Danau Singkarak; (30) Solok; (31) Lunang;<br />

(32) Sindang; (33) Pulau Halang; (34) Bagansiapiapi; (35) Kampar estuary; (36,Tanjung Datuk; (37) Tanjung<br />

Bakung; (38) Kualacenako; (39) Kuala Betara; (40) Tanjung Jabung; (41) Sungai Batang Hari; (42) Berbak<br />

National Park; (43) Banyuasin peninsula; (44) Tanjung Selokan; (45) Padang Sugihan Wildlife Reserve;<br />

(46) Tanjung Koyan; (47) Menggala; (48) Way Kambas National Park; (49) Telukbetung; (50) Ujung Kulon<br />

National Park; (51) Pulau Dua; (52) Serang; (53) Tangerang; (54) Pulau Rambut Wildlife Reserve; (55) Jakarta;<br />

(56) Muara Gembong; (57) Muara Wetan; (58) Muara Bungin; (59) Balubuk; (60) Rawa Gempol; (61) Tanjung<br />

Sedari; (62) Indramayu; (63) Cirebon; (64) Segara Anakan; (65) Nusa Kambangan; (66) Tegal; (67) Surabaya;<br />

(68) Baluran National Park; (69) Sumenep; (70) Gilimanuk; (71) Taliwang; (72) Panua Reserve; (73) Marisa;<br />

(74) Tanjung Panjang; (75) Kolumbi; (76) Palopo; (77) Polewali; (78) Danau Tempe; (79) Palima; (80) Maros;<br />

(81) Makassar; (82) Jeneponto; (83) Pulau Bokhari; (84) Ranomeeto; (85) Rawa Aopa Watumohai National<br />

Park; (86) Wolulu; (87) Danau Ambuau.<br />

Historical (pre-1950) Fairly recent (1950–1979) Recent (1980–present) Undated<br />

172

<strong>Mycteria</strong> <strong>cinerea</strong><br />

(Escott and Holmes 1980), between Makassar and Maros at Lanteboeng (5°05´S 119°28´E:<br />

Bishop in press), up to 30, March 1986 (Uttley 1987), 22 birds, February 1990 (Baltzer 1990),<br />

and c.3 km south-west of Ujung Pandang airport, three adults, January 1986 (Bishop in<br />

press); Mampie Game Reserve by strong report, recently (Baltzer 1990); Jeneponto, undated<br />

(Escott and Holmes 1980); ■ South-East Sulawesi Pulau Bokhari, Kota Kendari, 14, August<br />

1998 (R. Gregory-Smith in litt. 1999); Ranomeeto, Kota Kendari, one, September 1998 (R.<br />

Gregory-Smith in litt. 1999); Rawa Aopa Watumohai National Park, up to c.137 (largest<br />

flock 88) seen at Savanna, Mangrove, Aopa swamp, Kendari, Anaaha and Kolaka,<br />

September–October 1995 (Oriental Bird Club Bull. 24 [1996]: 59–65, Wardill et al. 1995),<br />

seven, August 1998 (R. Gregory-Smith in litt. 1999); Wolulu, “Kab. Kolaka”, eight, August<br />

1998 (R. Gregory-Smith in litt. 1999);<br />

Buton Danau Ambuau, November 1996 (Catterall undated); “square 78”, November 1996<br />

(Catterall undated); “square 74”, November 1996 (Catterall undated).<br />

POPULATION The estimated world population is 6,100 (Perennou et al. 1994), or more<br />

precisely, 6,000 in Indonesia and 100–150 in Cambodia and Peninsular Malaysia combined<br />

(Rose and Scott 1997).<br />

Thailand Although the scant evidence has been interpreted to suggest that the species<br />

might have occurred regularly in the south, possibly breeding along the coasts (Morioka and<br />

Yang 1990), it is perhaps more likely that it was always scarce in the country; it is now<br />

apparently locally extinct (Treesucon and Round 1990).<br />

Cambodia Early reports give the impression that the species was always uncommon in<br />

Cambodia (e.g. Delacour 1929b); it was “rare” in the country by the 1960s (Thomas 1964)<br />

and has apparently undergone subsequent declines (Scott 1992). Numbers are now thought<br />

to be very low, with an estimated 30 breeding pairs at Prek Toal and Prek Da near Tonle Sap<br />

lake being the only resident population reported in Indochina (Parr et al. 1996, Sun Hean in<br />

litt. 1997); the largest group reported recently contained 31 individuals near Tonle Sap in<br />

April 1999 (F. Goes and C. M. Poole in litt. 1999). No breeding birds were found in an<br />

extensive survey of waterbird breeding colonies around Tonle Sap in 1998, although locals<br />

reported that small colonies still exist (Goes et al. 1998b).<br />

Vietnam There is no unequivocal evidence that the species ever bred in the country and it<br />

is certainly now only a vagrant at best (Collar et al. 1994, Eames and Tordoff in prep.; see<br />

Remarks 2).<br />

Peninsular Malaysia Although Robinson and Chasen (1936) were able to compile “few<br />

formal records”, they nevertheless considered it “not rare in suitable localities”; it was, for<br />

example, “not uncommon” on the Selangor coast. Over the next few decades, however, none<br />

was observed on the Selangor coast by Madoc (ms) between 1944 and 1957 despite “many<br />

trips around the outer islands and mudflats”, while Medway and Wells (1976) added that<br />

“on many visits to the Selangor mudflats during 1961–71 this stork was never seen”. The<br />

Pulau Ketam heronry had long been abandoned by 1957 (Madoc ms), presumably because it<br />

was “much-raided” (Wells 1999). At that time the species was only known in Krian district,<br />

Perak (Medway and Wells 1976). In 1984 an aerial survey between Kuala Lumpur and<br />

Langkawi yielded sightings of 115 individuals, a group of 36 south of the Larut estuary and<br />

79 around the Kuala Gula area; this was thought to approximate to the entire population of<br />

Peninsular Malaysia (Parish and Wells 1985).<br />

Indonesia W. Davison (in Hume 1873b) mentioned “an enormous flock” in a large creek<br />

in Aceh, northernmost Sumatra, suggesting that the species was previously very common on<br />

Sumatra. By the end of the 1980s the island was indeed recognised as the global stronghold<br />

of the species, with a population estimated to be around 5,000 individuals (Silvius and<br />

Verheugt 1989). In 1985, 116 were counted in Lampung province (Milton and Marhadi 1985).<br />

Counts in October–November 1984 were of 3,053 birds in the provinces of Riau (703), Jambi<br />

173

Threatened birds of Asia<br />

(763) and South Sumatra (1,587); in July–August 1985 of 1,029 in Jambi (697) and South<br />

Sumatra (732); and again in March–April 1986 of 1,937 in Jambi (1,134), and South Sumatra<br />

(803); on the basis of these data these three provinces were judged to hold the majority of the<br />

world population (Danielsen and Skov 1985, Silvius 1988). In September 1988 at Tanjung<br />

Koyan 300–400 nests were estimated to be present, with a total of 500 birds including at least<br />

50 juveniles; at Tanjung Selokan 300 nests were estimated to be present, with a total of 150<br />

birds including several juveniles; and on the Banyuasin peninsula 280 nests were observed<br />

along with 250 adults and 100 juveniles (Danielsen et al. 1991a), with as many as 1,000 birds<br />

there subsequently (Verheugt et al. 1993). These welcome findings were in part offset by the<br />

subsequent discovery of the loss of the colony within Hutan Bakau Pantai Timor reserve,<br />

Jambi province (Danielsen et al. 1991b), which must be taken as reasonably likely to represent<br />

a real decline in overall numbers.<br />

Early in the twentieth century the species was clearly seasonally very common in Java,<br />

with large colonies (“many nests”, or 75–100 nests) noted in the Citarum delta (Bartels 1915–<br />

1930, Hoogerwerf 1936a). By the mid-1980s, the breeding population was tiny but the island<br />

experienced influxes of other birds (Lambert and Erftemeijer 1989); the total population of<br />

West Java was estimated at c.400 (356–408 individuals) (Allport and Wilson 1986; also<br />

Verheugt 1987). Over 1,000 individuals have been reported to visit the north-east coast of<br />

Java seasonally (Hancock et al. 1992), but this is possibly an overestimation. Surveys of the<br />

south coast of Central Java yielded a minimum of 164 birds, but without confirmation of<br />

breeding (Erftemeijer et al. 1988), and surveys in East Java found only 38 birds (Erftemeijer<br />

and Djuharsa 1988). Pulau Rambut may be the last breeding site on the north coast of Java,<br />

since the species is known to have ceased breeding on Pulau Dua in 1975 and at an unspecified<br />

date in the Brantas or Solo deltas of East Java, indicating a considerable decline; the maximum<br />

number of nests recently found was 10 in 1984 (14 given in Allport and Wilson [1986]). A<br />

recent record of 170 individuals on Madura (Oriental Bird Club Bull. 24 [1996]: 59–65)<br />

suggested that the island may support an important numbers of the species, at least seasonally.<br />

The population on Sulawesi appears to have increased in recent years, although this is<br />

almost certainly a result of greater observer coverage and surveying of new areas, especially<br />

in South-east Sulawesi (Bishop in press). As many as 73 birds were discovered at a variety of<br />

coastal sites in South Sulawesi in 1986, suggesting a modest resident population in the province<br />

(Uttley 1987). South-east Sulawesi may hold a small but valuable population, with c.100 in<br />

Rawa Aopa Watumohai National Park in 1995 (Wardill et al. 1995). Breeding has not been<br />

proven on the island (Bishop in press), although sightings of juveniles suggests that it is very<br />

likely to occur. In 1996 the species was also noted at three localities on Buton, with 21 birds<br />

in one tree, and an immature also seen, suggesting local breeding (Catterall undated).<br />

ECOLOGY Habitat Throughout much of its range, the Milky Stork is essentially a coastal<br />

species, favouring mangroves, mudflats and estuaries (Hancock et al. 1992). It also feeds on<br />

ricefields and fishponds (Verheugt 1987). This is certainly the case in its Sumatran heartland,<br />

although it occasionally visits “lebaks” (backswamps along river floodplains) up to 150 km<br />

from the coast; during spring tides, birds often roost in remnant trees in ricefields (Verheugt<br />

et al. 1993; also Danielsen and Skov 1985, 1987). Roost sites are sometimes in the crowns of<br />

tall mangrove trees (Hancock et al. 1992), although they also regularly roost on the ground<br />

out on mudflats or in marshes (Bartels 1915–1930), a factor that makes the species relatively<br />

easy to count, even from the air (e.g. Parish and Wells 1985). In Peninsular Malaysia, the<br />

species is “more exclusively marine” than its congener the Painted Stork (Robinson and<br />

Chasen 1936), the suggestion being that the two separate ecologically when they meet<br />

(Morioka and Yang 1990). However, they were reported to frequent the same marshy plains<br />

in Cambodia, often in the same flock (Delacour and Jabouille 1931), and recent reports from<br />

Cambodia again suggest that they use or used similar habitats (Mundkur et al. 1995a, C. M.<br />

174

<strong>Mycteria</strong> <strong>cinerea</strong><br />

Poole in litt. 1997); moreover, local people report that they breed alongside each other in<br />

flooded forest around Tonle Sap (Goes et al. 1998b). In Cambodia, Milky Storks frequent<br />

flooded forest and mangrove in both freshwater and coastal habitats (Mundkur et al. 1995a,<br />

Sun Hean in litt. 1997). Concentrations have been recorded at fishponds in Sulawesi (Andrew<br />

and Holmes 1990). Although they are said to be generally shy and vulnerable to disturbance<br />

(Verheugt 1987), this applies to foraging individuals, as nesting birds can often be approached<br />

quite closely (Allport and Wilson 1986, Hancock et al. 1992).<br />

Food At Sungai Burong, Malaysia, the bulk of the diet appeared to be large mudskippers<br />

Periophthalmus 10–23 cm in length; the estimated weight of fish eaten in one observation of<br />

39 minutes was 225 g (Swennen and Marteijn 1987). In Indonesia the species has also been<br />

reported consuming snakes and frogs (Hoogerwerf and Siccama 1937–1938), fish (including<br />

a large “blanak”, presumably a kind of fish) (Bartels 1915–1930), and feeding eels,<br />

mudskippers and 20 cm fish to nestlings (Hoogerwerf 1936b).<br />

Often feeding in aggregations with other wading birds, such as Lesser Adjutant Leptoptilos<br />

javanicus and egrets Ardeidae (Verheugt 1987, Hancock et al. 1992), the species generally<br />

employs a tactile foraging technique, involving standing still (sometimes for several minutes)<br />

or walking through mud and usually very shallow (but sometimes deeper) water, probing<br />

with a partly opened bill, or drawing it in an arc from side to side, until a prey item is located<br />

by touch (Bartels 1915–1930, Swennen and Marteijn 1987, Silvius 1988, Indrawan et al.<br />

1993b); it has also been seen to seek food by foot-stirring (Hoogerwerf 1936b). Less frequently,<br />

individuals either detect prey by sight or root them from their burrows (Swennen and Marteijn<br />

1987, Silvius 1988). On locating a mudskipper’s hole an individual will usually probe its bill<br />

in the immediate vicinity 10–15 times, sometimes immersing the whole bill and head into the<br />

mud and then hauling out the prey once it has been secured in the bill (del Hoyo et al. 1992).<br />

Birds have been observed feeding spaced 50–100 m apart (A. Elliott per T. P. Inskipp in litt.<br />

1997), but sometimes they will move in a single tight flock, flushing fish in shallow water<br />

(Indrawan et al. 1993b). Where food is abundant, foraging bouts are of relatively short<br />

duration, and roosting or comfort behaviour is undertaken for protracted periods (Hancock<br />

et al. 1992). At the Pulau Dua colony, considerable nocturnal activity was noted, with birds<br />

both foraging and visiting nests during hours of darkness, at least under a full moon (Hancock<br />

et al. 1992).<br />

Breeding Season At Tonle Sap, Cambodia, egg-laying apparently takes place during the<br />

dry season (as with all other waterbirds at the site) in January and February (Parr et al.<br />

1996), while in Malaysia two nests contained three eggs on 18 August (Robinson and Chasen<br />

1936) and the Kuala Gula colony was active in November (Hancock et al. 1992). In Indonesia,<br />

breeding occurs during the dry season that usually lasts until October (Hancock et al. 1992).<br />

Clutches taken on Java date from March, May and July (Hellebrekers and Hoogerwerf 1967),<br />

a Javan colony mostly contained fledged and almost full-grown young (with one clutch<br />

unhatched) in July (Hoogerwerf 1936a), and eggs are apparently sometimes laid in August<br />

(Hancock et al. 1992). On 19 July 1919, nests were active at the Citarum delta on Java, most<br />

containing three eggs, some with newly hatched chicks and a very few with chicks close to<br />

fledging (Bartels 1915–1930). In Sumatra a bird was seen in breeding plumage in May (Nash<br />

and Nash 1985) and egg-laying occurs in June–August (Hancock et al. 1992). Dry-season<br />

breeding probably coincides with maximum fish stocks, following the rainy season (Hancock<br />

et al. 1992), and presumably increased ease of prey capture as water levels drop (although<br />

this is presumably does not apply to birds feeding in tidal areas).<br />

Nest site and structure Breeding is colonial, often occurring in multi-species aggregations,<br />

with Milky Stork nests often numbering only 10–20, but sometimes up to several hundred<br />

(Hancock et al. 1992). In Sumatra the species has been recorded nesting alongside Lesser<br />

Adjutant, Black-headed Ibis Ibis melanocephala and several species of heron Ardeidae<br />

(Danielsen et al. 1991a). Nesting around Tonle Sap presumably takes place in large colonies<br />

175

Threatened birds of Asia<br />

containing Painted Stork, Lesser Adjutant and Spot-billed Pelicans Pelecanus philippensis<br />

(Mundkur et al. 1995a, Goes et al. 1998b).<br />

The major breeding colonies found in Sumatra in September 1988 were all in mangrove<br />

back swamps; at Tanjung Koyan the colony was some 2 km from the coast, in dense<br />

Acrostichum fern vegetation, with nests built in 3–4 m high bushes around a small (900 m²)<br />

pool; at Tanjung Selokan it was 1–2 km from the coast, with nests 5–15 m up in 10–12 dead<br />

trees within a flooded area 15 ha in extent; on the Banyuasin peninsula it was 3–4 km inland,<br />

2–6 m up in 10–15 small bushes near a 2,500 m² pool in dense Acrostichum fern vegetation<br />

(Danielsen et al. 1991a); and at Kuala Betara, it was situated in the outer mangrove fringe in<br />

nine trees (probably Avicennia, although some were later identified as “red mangrove”<br />

Rhizophora apiculata) 8–12 m high (Danielsen and Skov 1985, 1987; also Silvius 1988). Two<br />

other nesting colonies were also reported one and three hours inland by canoe (Danielsen<br />

and Skov 1985). On Java a colony of 75–100 nests was sited in a group of large “black<br />

mangrove” Avicennia marina covering c.4.5 ha; nest-trees generally held 5–7 nests, sometimes<br />

10, rarely only 2–3 (Hoogerwerf 1936a). At the Citarum delta only very tall trees were used,<br />

one of these containing 22 nests (Bartels 1915–1930). In the same tree species, nests were<br />

placed at heights of 8–30 m (Verheugt 1987), usually 30 m up on Pulau Rambut, but originally<br />

(prior to disturbance) down to 4 m above the ground on Pulau Dua (Hancock et al. 1992). In<br />

Malaysia, a colony of 20 nests was situated 8–10 m up both live and dead trees, mostly the<br />

latter (Siti Hawa Yatim 1990); in another case two nests were placed in the tops of mangroves<br />

(Robinson and Chasen 1936). Nests are fairly bulky structures of sticks, lined with fresh<br />

leafy twigs, in general resembling the nests of Grey Herons Ardea <strong>cinerea</strong> but containing<br />

thicker branches (Hoogerwerf 1936a, Robinson and Chasen 1936). Twigs and fresh leaves<br />

are sometimes collected for the nest from some distance away (Bartels 1915–1930).<br />

Clutch, incubation and fledging Nine clutches from Java consisted of three eggs (Hellebrekers<br />

and Hoogerwerf 1967), although nests in one large colony held mostly two young, one with<br />

one and a few with three (Hoogerwerf 1936a), and clutches of four eggs have been recorded<br />

(Hoogerwerf 1949). In 1984, nests at Pulau Rambut, Java, mostly contained two young<br />

(Verheugt 1987). Two nests in Malaysia both contained three young (Robinson and Chasen<br />

1936). The incubation period is estimated at 27–30 days; by 6–7 weeks the young are able to<br />

leave the nest and fly poorly, and by eight weeks they fly well but are still fed in the nest by<br />

parents (Hoogerwerf 1936b). Small young are fed more frequently than large young; before<br />

they are four weeks old chicks may be fed twice per hour (presumably on small items), whereas<br />

older nestlings may only be fed once per afternoon (presumably on larger items) (Hoogerwerf<br />

1936b). When temperatures are high, adults sometimes bring water to the nest and drool it<br />

from their bills to cool the nestlings or allow them to drink (Hancock et al. 1992).<br />

Migration Most waterbirds breeding around Tonle Sap vacate the area during the wet<br />

season, visiting wetlands across Cambodia (C. M. Poole in litt. 1998, Goes 1999a). The recent<br />

sighting of birds in the Gulf of Thailand coincides with this annual wet-season exodus<br />

(C. M. Poole verbally 1999), and indeed the species may be an overlooked regular but rare<br />

visitor to the area (P. D. Round in litt. 1999).<br />

In Peninsular Malaysia the Perak population is essentially resident (Wells 1999). The few<br />

sightings from Johor are probably occasional wanderers from the Riau and Jambi populations<br />

on Sumatra, only 70 km distant (Hawkins and Howes 1986; see Remarks 1). The record<br />

from north-west Bali in October 1982 was of a bird flying east during a raptor migration<br />

(Ash 1982, NJC), and other sightings to the east in Sumbawa suggest that individuals<br />

occasionally wander for great distances. In addition, two birds were observed crossing the<br />

Sunda Straits in September 1984 (Allport and Wilson 1986), a flock of presumed immigrants<br />

was seen flying east at Serang, West Java, again in September 1984, and spring migration<br />

was noted in April 1985 when two small groups were seen flying in a north-westerly direction,<br />

leaving mainland Java and travelling towards Sumatra (Verheugt 1987). Although such<br />

176

<strong>Mycteria</strong> <strong>cinerea</strong><br />

movements have not been considered true migration (Silvius and Verheugt 1989), the likely<br />

provenance of all these birds is south-east Sumatra, suggesting a minor annual migration<br />

(Hancock et al. 1992).<br />

THREATS The main threats to the survival of the species are human disturbance, hunting<br />

and habitat loss. A review of threats to the species is given by Verheugt (1987).<br />

Persecution, disturbance and trade In all portions of its range the species is threatened by<br />

poaching and interference with colonies (Hancock et al. 1992). Cambodia The flooded forest<br />

at Prek Toal, near Tonle Sap lake, supports one of the most important waterbird colonies in<br />

South-East Asia (Parr et al. 1996; see Measures Proposed under Greater Adjutant Leptoptilos<br />

dubius). The exploitation of eggs and chicks was identified as the principal threat to the<br />

continued survival of these colonies (Parr et al. 1996, Sun Hean in litt. 1997; see Threats<br />

under Greater Adjutant). As in much of South-East Asia, wildlife is seen as a delicacy much<br />

sought after by city dwellers, and middlemen travel from Battambang and Siem Reap to the<br />

Prek Toal area, often providing advance monies for waterbird chicks months before the<br />

breeding season; stork chicks are also often consumed at Khmer New Year feasts in the<br />

area, as the meat is preferred and the price is low (Ear-Dupuy et al. 1998). It was thought<br />

that, along with Painted Stork, this species is one of the most favoured by local waterbird<br />

collectors at Prek Toal because of the taste and manageable weight of its chicks (Parr et al.<br />

1996; see Remarks 3), but this conclusion has not been supported by later research (Ear-<br />

Dupuy et al. 1998). These demands cause much of the exploitation at Tonle Sap colonies,<br />

resulting in an extremely low ratio of offspring to adults for all large waterbirds, which<br />

implies poor breeding success and low recruitment (Parr et al. 1996). Other local methods of<br />

waterbird exploitation include the use of fishing hooks and monofilament nylon lines or<br />

hooks mounted on sticks to snare adult birds (Mundkur et al. 1995a, Parr et al. 1996), but<br />

this mostly targets small or medium-sized waterbirds. Spring-traps baited with decoy birds<br />

are a potentially serious threat (Parr et al. 1996). Peninsular Malaysia Given the vast mudflats<br />

along the western Malaysian Peninsula, the local decline of the species cannot easily be<br />

attributed to any shortage in foraging habitat or food supply (although see Pollution under<br />

Lesser Adjutant); persecution and disturbance at nesting colonies (along with destruction of<br />

nesting habitat) are almost certainly the cause of apparent declines (Swennen and Marteijn<br />

1985, Wells 1999). The Pulau Ketam heronry, in which this species once nested, was thought<br />

to have been abandoned owing to high levels of hunting and disturbance (DWNPPM 1987).<br />

Indonesia The future of the species in South Sumatra remains uncertain partly owing to<br />

continuing local demand for food and trade (Silvius and Verheugt 1989). The breeding colony<br />

at Hutan Bakau Pantai Timor mangrove reserve had disappeared in 1989, along with much<br />

of the mangrove within the area; this was possibly caused by a pulse of illegal trade in the<br />

species, when 40–50 young birds were shipped to zoos within South-East Asia and western<br />

Europe at a time when the only other known (publicised) colony was the small one on Pulau<br />

Rambut, Java (Danielsen et al. 1991b). In the early 1990s, 70 Milky Storks were kept in<br />

captivity in nine zoos outside Indonesia (Hancock et al. 1992). D. A. Holmes (in litt. 1999)<br />

commented that “without urgent, strong, positive intervention it is likely that all the breeding<br />

colonies in Sumatra will be destroyed within a few years”, especially given the partial<br />

breakdown of law and order occurring in some regions. Bartels (1915–1930) reported that<br />

on Java no persecution of adult Milky Storks occurred and the birds were therefore very<br />

tame; they were often kept as pets, however, indicating that young ones were taken from<br />

colonies. The fact that the species no longer breeds on Java suggests that this pressure grew<br />

too intense or that disturbance of nesting colonies increased unsupportably. During the<br />

Japanese occupation of Indonesia (1942–1945) management of Pulau Dua was interrupted;<br />

severe damage to mangrove habitat was thereby incurred with a negative impact on numbers<br />

of the species (Hoogerwerf 1947a). The loss of this stork (in common with four other colonial<br />

177

Threatened birds of Asia<br />

waterbirds) from the breeding avifauna of Pulau Dua in 1975 coincided with increased access<br />

to the island (it became joined to the mainland by a spit of accumulated silt in the mid-1970s,<br />

allowing pedestrian access to humans and other predators) and so is probably related to<br />

disturbance (Milton and Marhadi 1985, Verheugt 1987, Hancock et al. 1992).<br />

Habitat loss and modification Throughout its range the species is threatened by habitat<br />

loss as a result of mangrove deforestation, tidal rice cultivation, fish- and prawn-farming<br />

and (in Indonesia at least) human resettlement (Luthin 1987, Verheugt 1987, Collar et al.<br />

1994, Hancock et al. 1992). In South-East Asia all large waterbirds are “suffering reduction<br />

in available breeding sites through felling of trees providing nest sites and loss of foraging<br />

areas to urban and industrial development” (Kushlan and Hafner 2000). In particular,<br />

mangrove forests throughout the region are being cleared at a dramatic rate for development,<br />

for the commercial production of firewood and charcoal, and for fish-farming (Silvius et al.<br />

1986, Verheugt 1987, Whitten et al. 1987b,c, Parr 1994b, Kushlan and Hafner 2000). Cambodia<br />

Large tracts of swamp forest around Tonle Sap have apparently already been logged and<br />

converted to agriculture; forest clearance is currently proceeding at a slow rate but as timber<br />

resources become depleted peripherally, the pressure to exploit the remaining habitat is set<br />

to intensify (Scott 1992, Parr et al. 1996). Intentional burning of the flooded forest at this site<br />

was noted in the dry season, but the extent of damage was not determined (Parr et al. 1996).<br />

Siltation may pose another threat. Although it has perhaps been exacerbated by widespread<br />

deforestation of the catchment area, and by a series of small dams constructed by the Khmer<br />

Rouge (Scott 1989), there is no evidence to support this and, in fact, some dam/irrigation<br />

schemes in Cambodia have produced excellent habitat for large waterbirds (e.g. Ang Trapeang<br />

Thmor Reserve) (C. M. Poole in litt. 1999). Ironically, the increasing prospect of peace in the<br />

region is perhaps one of the most serious threats to the waterbirds of Tonle Sap, as political<br />

and military stability will probably lead to a resumption of plans for flood control, drainage<br />

and irrigation as part of a regional development scheme (Scott 1992); on the other hand, of<br />

course, instability reduces the chances of establishing an effective protected-area network in<br />

Cambodia (Parr et al. 1996). Vietnam Hancock et al. (1992) stated that “this species was<br />

essentially eliminated from Vietnam by the widespread destruction of mangrove swamps<br />

during the Southeast Asian War”, going on to suggest that “extensive mangrove reforestation<br />

and protection by wardens may have resulted in some recolonization in recent years”. There<br />

is, in fact, little evidence to suggest that the species ever bred in Vietnam (see under Population)<br />

or that it was exterminated by habitat loss. Moreover, the mangrove reforestation programme<br />

is apparently ineffective, and wardening of suitable areas almost non-existent (S. T. Buckton<br />

verbally 2000). Peninsular Malaysia An account of threats to coastal wetlands and mangroves<br />

(including Kuala Gula) in the peninsula appears in Threats under Lesser Adjutant. Indonesia<br />

The future of the species in South Sumatra remains uncertain owing to plans to convert tidal<br />

forests into large-scale brackish-water fish-farms and to implement various logging and<br />

conversion schemes (Silvius and Verheugt 1989). Large areas of lowland forest in Sumatra,<br />

including swamp forest, have been severely adversely affected by widespread fires (see Threats<br />

under Hook-billed Bulbul Setornis criniger); for example, fire destroyed habitat in Berbak<br />

National Park in 1997 (Legg and Laumonier 1999). There are or were dangers associated<br />

with all three major breeding colonies on Sumatra in 1988, although positive opportunities<br />

existed (see Measures Taken and Measures Proposed). The disappearance of the breeding<br />

colony at Hutan Bakau Pantai Timor, along with much of the mangrove within the area,<br />

was possibly attributable to substantial incursions by farmers and loggers apparently unaware<br />

of the existence of the reserve (Danielsen et al. 1991b). Padang Sugihan reserve has been<br />

overrun by local settlers (Rudyanto verbally 2000). The important wetland of Segara Anakan<br />

in southern Central Java has been a source of concern through steady siltation and plans for<br />

its conversion to rice (Erftemeijer et al. 1988). In total, an estimated 1,000 km 2 of coastal<br />

wetland is lost in Indonesia per annum (Verheugt 1987). Rapid degradation of coastal<br />

178

<strong>Mycteria</strong> <strong>cinerea</strong><br />

mangroves and swamps in Sulawesi was observed during December 1997 along the east and<br />

south coasts of the northern peninsula (Kasinbar to Tilamuta) and does not bode well for<br />

the local population of this species (Bishop in press). The degree of habitat loss in south and<br />

south-eastern Sulawesi is not known.<br />

Pollution Industrial and agricultural pollution in Cambodia and Peninsular Malaysia is<br />

discussed in Threats under Lesser Adjutant.<br />

MEASURES TAKEN The species has been listed on Appendix I of CITES since 1987. It is<br />

legally protected in Malaysia and Indonesia.<br />

Protected areas Cambodia Prek Toal is a core area of Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve (C. M.<br />

Poole in litt. 1999; but see Measures Taken and Measures Proposed under Greater Adjutant).<br />

Ream National Park might protect a breeding population (J. W. K. Parr in litt. 1998) and<br />

recent reports of immature birds in the area lend weight to this prospect (C. M. Poole in litt.<br />

1999); extensive mangroves are located immediately east of the reserve. Peninsular Malaysia<br />

The species receives some protection at Kuala Gula in Matang Mangrove Forest Reserve. It<br />

also occurs in Benut Forest Reserve but it is unclear what level of protection this entails.<br />

Indonesia The large colony at Tanjung Koyan, South Sumatra, is within mangrove designated<br />

as protection forest, and although part of the area has been identified for agricultural<br />

settlement the site should not be affected if the status of the mangrove is maintained (Danielsen<br />

et al. 1991a). Other colonies are in the Berbak National Park and Way Kambas National<br />

Park (Sumatra), Pulau Rambut Strict Nature Reserve (Java) and Rawa Aopa Watumohai<br />

National Park (Sulawesi).<br />

Reduction of persecution Cambodia An account of relevant measures at colonies near<br />

Tonle Sap appears under Greater Adjutant.<br />

Education Cambodia The species is included in awareness material (books and posters)<br />

produced and distributed by the Wildlife Protection Office as part of an ongoing campaign<br />

to reduce the exploitation and hunting of large waterbirds (Veasna 1999, C. M. Poole in litt.<br />

1999). Educational videos have also been shown to some villagers, emphasising the laws<br />

prohibiting hunting and the need to conserve large waterbirds (Veasna 1999).<br />

Captive breeding Malaysia A captive breeding programme at Zoo Negara, Kuala Lumpur,<br />

resulted in four pairs producing 12 offspring up to 1990 (ICBP/IWRB Storks, Ibises and<br />

Spoonbills Specialist Group Newsletter 3, 1/2 [1990]: 5). Individuals were released from captivity<br />

at Kuala Selangor Nature Park, Selangor (Enggang 4, 3 [1996]), and by 2000 the zoo had 60<br />

birds, but although some of these had been released into the park no breeding had occurred<br />

(Suara Enggang 4, July–August [2000]: 30–31).<br />

MEASURES PROPOSED Accounts of all measures proposed in the Tonle Sap region,<br />

Cambodia, appear in equivalent sections under Greater Adjutant. Conservation action for<br />

this species also broadly overlaps that suggested for the Lesser Adjutant in Malaysia and<br />

Indonesia (see relevant account).<br />

Protected areas Malaysia The level and area of protection at Matang Mangrove Forest<br />

Reserve and Benut Forest Reserve should be increased. Proposals relating to forestry practices<br />

in these areas appear under Lesser Adjutant. Indonesia The location of the inland colonies at<br />

Sungei Gapung and Sungei Siput, South Sumatra, the latter reputedly holding “hundreds of<br />

nests” (Danielsen and Skov 1985), is clearly important, and the protection of these and the<br />

colony in mangrove at Kuala Betara (Hutan Bakau Pantai Timor mangrove reserve), if still<br />

extant, is imperative. The breeding colony at Tanjung Selokan is or was within an area<br />

proposed for fishpond development, but a nature reserve of 100 km 2 has now been proposed<br />

(Danielsen and Verheugt 1990, Danielsen et al. 1991a). The colony on the Banyuasin peninsula<br />

is similarly within an area designated for fishpond development, in spite of being on acidic<br />

soils and falling within protection forest, but a major proposal to create the Sembilang Wildlife<br />

179

Threatened birds of Asia<br />

Reserve, covering 3,875 km 2 , has been formulated to protect not only the storks and another<br />

34 globally threatened wildlife species but also a major migration stopover site and the natural<br />

spawning areas for 70% of the province’s coastal fisheries (Danielsen and Verheugt 1990,<br />

Danielsen et al. 1991a). Silvius and Verheugt (1989) called for network of coastal nature or<br />

wildlife reserves to be established in Riau, Jambi and South Sumatra provinces, Sumatra.<br />

Repeated observations in Sulawesi come from an area of coastal mangroves, swamp forest<br />

and shallow lake(s) in and around the proposed Tanjang Panjang Reserve (FAO 1982), a<br />

site that clearly deserves protection.<br />

Research and monitoring Further survey work is required, as is continued monitoring of<br />

all subpopulations at key sites (see Remarks 4). Commercial harvesting of swamp forest<br />

needs further study so that methods can be improved from the viewpoint of waterbird<br />

conservation. Research programmes are also required on the general ecology and seasonal<br />

movements of the species. In Indonesia, surveys of Sulawesi should seek to establish its<br />

status, distribution and management requirements. Key colonies need to be studied where<br />

possible so that reproductive success can be gauged, trends tracked and the source of<br />

significant threats identified.<br />

Reduction of persecution Colonies need to be protected from disturbance and from egg or<br />

chick collection wherever possible. In some cases this will necessitate some form of breeding<br />

season surveillance, perhaps in conjunction with research or ecotourism, and certainly in<br />

conjunction with local education initiatives.<br />

Education The success of conservation programmes and protected areas for the species<br />

in Malaysia “will depend much on actively interesting the local community” (Wells 1999); to<br />

address this need, community awareness projects should target relevant settlements. In<br />

Indonesia a public awareness campaign should inform the local communities, including<br />

fishermen who live semi-permanently offshore, of the conservation and protection status of<br />

the species (Silvius and Verheugt 1989).<br />

REMARKS (1) Wells (1999) took the clustering of records into five nodes to be “suggestive<br />

of at least as many past colonies”, rather than the result of wandering birds. Further<br />

unconfirmed records from the southern portion of the peninsula include a group seen at<br />

Kampung Telok Jawa, near Pasir Gidang, south Johor, Peninsular Malaysia, in June 1998,<br />

after a newspaper report of 14 in November 1997: these birds were suspiciously confiding<br />

and therefore probably escapees from Singapore Zoo (Suara Enggang July–August 1998).<br />

An earlier report of 14 flying north to south near Serangoon, Singapore, October 1997 (H.<br />

Jensen in litt. 1999), seems likely to refer to the same flock of birds. (2) Although rumours<br />

have circulated that “a former colony site in southern Vietnam has been recolonized in recent<br />

years” (Verheugt 1987) or that “some birds have apparently recolonized Vietnam since the<br />

war of 1963–75” (Hancock et al. 1992), there is no firm evidence of this. Ornithological<br />

surveys of wetlands throughout the Mekong delta in 1999 failed to find the species (Buckton<br />

et al. 1999), and there are no confirmed recent records from elsewhere in Vietnam (Nguyen<br />

Cu in litt. 1997, Eames and Tordoff in prep.). A possible record from Cat Tien National<br />

Park, Dong Nai, in December 1988 (Morris 1994), and other records from Ca Mau, Kien<br />

Giang and Minh Hai provinces (Le Dien Duc and Le Dinh Thuy 1987, Verheugt 1987, Le<br />

Dien Duc 1989, 1993a, Scott 1989) are all thought to be mistaken (J. C. Eames in litt. 2001).<br />

(3) The Milky Stork is often not differentiated from the Painted Stork by locals in Cambodia<br />

(Parr et al. 1996). Waterbird harvesters reportedly collected 6,570 eggs and 2,482 chicks of<br />

Painted Stork from the Prek Toal colony in the 1995–1996 breeding season, totals that might<br />

contain small numbers of Milky Stork eggs (Parr et al. 1996). (4) Care should be taken<br />

during survey work to distinguish between this species and Painted Stork. Their similarity<br />

(especially of juveniles) makes the Milky Stork easy to overlook, especially at sites such as<br />

Tonle Sap, Cambodia, where Painted Storks are much commoner (Goes et al. 1998b).<br />

180