3 - Are you looking for one of those websites

3 - Are you looking for one of those websites

3 - Are you looking for one of those websites

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Partners <strong>for</strong> Water Programme<br />

International Agricultural Centre<br />

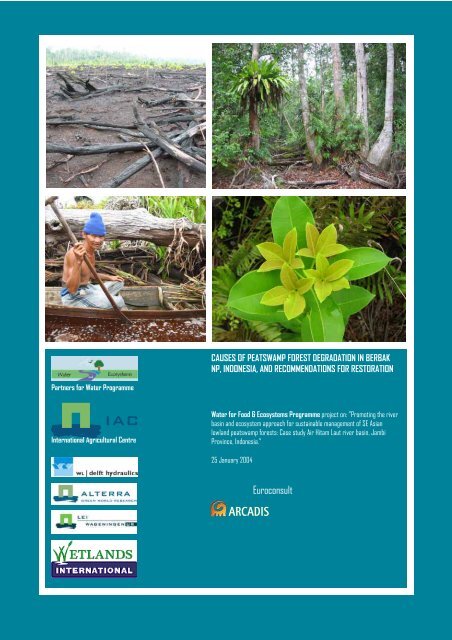

CAUSES OF PEATSWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK<br />

NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

Water <strong>for</strong> Food & Ecosystems Programme project on: ”Promoting the river<br />

basin and ecosystem approach <strong>for</strong> sustainable management <strong>of</strong> SE Asian<br />

lowland peatswamp <strong>for</strong>ests: Case study Air Hitam Laut river basin, Jambi<br />

Province, Ind<strong>one</strong>sia.”<br />

25 January 2004<br />

Euroconsult

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST<br />

DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP,<br />

INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

FOR RESTORATION<br />

by Wim Giesen<br />

ARCADIS Euroconsult<br />

Part <strong>of</strong> the project on<br />

“Promoting the river basin and ecosystem approach <strong>for</strong> sustainable management <strong>of</strong> SE Asian<br />

lowland peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests: Case study Air Hitam Laut river basin, Jambi Province, Ind<strong>one</strong>sia.”<br />

Water <strong>for</strong> Food and Ecosystems Programme<br />

INTERNATIONAL AGRICULTURAL CENTRE (IAC)<br />

IN COOPERATION WITH<br />

ALTERRA<br />

ARCADIS EUROCONSULT<br />

WAGENINGEN UNIVERSITY / LEI<br />

WL / DELFT HYDRAULICS<br />

WETLANDS INTERNATIONAL<br />

25 JANUARY 2004

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

Contents<br />

Abbreviations, acronyms & glossary ______________________________________________ 4<br />

Background ____________________________________________________________________ 6<br />

Summary _______________________________________________________________________ 7<br />

Acknowledgements _____________________________________________________________ 9<br />

1 Introduction ________________________________________________________________ 11<br />

1.1 Introduction to Southeast Asian peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests___________________________ 11<br />

1.1.1 Brief introduction to Peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests in Southeast Asia _______________ 11<br />

1.1.2 Recent history <strong>of</strong> SE Asian peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests _________________________ 14<br />

1.2 Introduction to Berbak NP_________________________________________________ 16<br />

1.2.1 Brief description <strong>of</strong> the natural conditions <strong>of</strong> the Park ___________________ 16<br />

1.2.2 Brief history <strong>of</strong> the Park_____________________________________________ 18<br />

2 Assessment <strong>of</strong> present condition <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP ________________________________ 20<br />

2.1 Condition <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP as reported by others ________________________________ 20<br />

2.2 Assessment <strong>of</strong> condition <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP based on satellite imagery________________ 22<br />

2.3 Fieldwork and observations <strong>of</strong> state <strong>of</strong> habitats at Berbak NP ___________________ 27<br />

2.3.1 Fieldwork methodology ____________________________________________ 27<br />

2.3.2 Fieldwork results __________________________________________________ 29<br />

2.3.3 General observations during fieldwork ________________________________ 32<br />

3 Cause(s) <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est degradation in Berbak NP ______________________ 34<br />

3.1 Assessments by others____________________________________________________ 34<br />

3.1.1 General assessments _______________________________________________ 34<br />

3.1.2 Hotspot analyses __________________________________________________ 36<br />

3.2 Assessment based on present field observations ______________________________ 36<br />

3.3 Likely history/scenarios leading to present condition <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP _______________ 38<br />

3.4 Conclusions & discussion__________________________________________________ 39<br />

4 Peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est restoration opportunities__________________________________ 44<br />

4.1 Degradation seres and natural regeneration <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est in Southeast Asia 44<br />

4.1.1 Degradation seres & regeneration in the region ________________________ 44<br />

4.1.2 Degradation seres & regeneration in Ind<strong>one</strong>sia _________________________ 47<br />

4.2 Attempts at peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est restoration in Southeast Asia ___________________ 49<br />

4.2.1 Peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est restoration in Southeast Asia________________________ 49<br />

4.2.2 Restoration attempts In and around Berbak NP _________________________ 54<br />

4.3 Identification <strong>of</strong> promising species <strong>for</strong> restoration programmes__________________ 57<br />

4.3.1 Recognised by others ______________________________________________ 57<br />

4.3.2 Identified during the present survey __________________________________ 61<br />

4.4 Requirements <strong>for</strong> replanting programmes____________________________________ 63<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 2

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

5 Recommendations <strong>for</strong> restoration <strong>of</strong> degraded peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est at Berbak NP _ 66<br />

5.1 Mid-upper catchment <strong>of</strong> the Air Hitam Laut river basin ________________________ 66<br />

5.2 Centre <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP _____________________________________________________ 67<br />

6 Recommendations <strong>for</strong> the Project’s peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est restoration programme __ 69<br />

6.1 Recommendations <strong>for</strong> improvement <strong>of</strong> the existing programme _________________ 69<br />

6.2 Budget and recommended Work Plan <strong>for</strong> the current project ___________________ 73<br />

7 Recommendations <strong>for</strong> capacity building in re<strong>for</strong>estation techniques & peat swamp<br />

management _______________________________________________________________ 75<br />

7.1 Local concession holder___________________________________________________ 75<br />

7.2 National Park staff _______________________________________________________ 75<br />

8 Conclusions ________________________________________________________________ 77<br />

References ____________________________________________________________________ 82<br />

Annex 1 Itinerary ________________________________________________________________ 90<br />

Annex 2 Site survey results: relevees ________________________________________________ 94<br />

Annex 3 Summary <strong>of</strong> site characteristics____________________________________________ 102<br />

Annex 4 Bird observations _______________________________________________________ 103<br />

Annex 5 Species common in burnt areas ___________________________________________ 106<br />

Annex 6 Terms <strong>of</strong> reference <strong>for</strong> SRS _______________________________________________ 108<br />

Annex 7 Photographic summary __________________________________________________ 111<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 3

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

Abbreviations, acronyms & glossary<br />

AHD Air Hitam Dalam<br />

AHL Air Hitam Laut<br />

asl Above Sea Level<br />

CCFPI Climate Change, Forests and Peatlands in Ind<strong>one</strong>sia (project)<br />

CIFOR Center <strong>for</strong> International Forestry Research (based in Bogor)<br />

CPI Caltex Pacific Ind<strong>one</strong>sia<br />

cukong Local term <strong>for</strong> broker, mainly used in a negative sense<br />

DANCED Danish Cooperation <strong>for</strong> Environment and Development<br />

dbh Diameter at breast height (= <strong>for</strong>estry term)<br />

Dinas Kehutanan Forest Service<br />

FFPCP Forest Fire Prevention and Control Project<br />

FRIM Forest Research Institute Malaysia<br />

GEF Global Environment Facility<br />

GIS Geographic In<strong>for</strong>mation System<br />

ha Hectares<br />

HLG Hutan Lindung Gambut (Peat Protection Forest)<br />

HP Hutan Produksi (Normal Production Forest)<br />

HPH Hak Pengusahan Hutan (Forest Concession Right)<br />

HPT Hutan Produksi Terbata (Limited Production Forest)<br />

HTI Hutan Tanaman Industri (Industrial Tree-crop Estate)<br />

IPB Institut Pertanian Bogor (Agricultural Institute Bogor)<br />

IUCN International Union <strong>for</strong> the Conservation <strong>of</strong> Nature and Natural<br />

Resources (World Conservation Union)<br />

jelutung Dyera species; in the PSF <strong>of</strong> eastern Sumatra this is Dyera lowii<br />

(Apocynaceae)<br />

JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency<br />

kempas Koompassia malaccensis (Leguminosae)<br />

KSDA Konservasi Sumber Daya Alam (Conservation <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources)<br />

department representing PHPA (now PKA) in the provinces<br />

LIPI National Science Agency Ind<strong>one</strong>sia<br />

Nipa Nypa fruticans (<strong>Are</strong>caceae)<br />

NP National Park<br />

NTFP Non-Timber Forest Product<br />

OKI Ogan-Komering Ilir district (in South Sumatra)<br />

PHPA (Direktorat Jenderal) Perlindungan Hutan dan Pelestarian Alam<br />

(Directorate General <strong>of</strong>) Forest Protection and Nature Conservation;<br />

now DG <strong>of</strong> Nature Conservation<br />

PSF Peat Swamp Forest<br />

PT. Limited Company<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 4

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

PT. DHL Dyera Hutan Lestari (plantation concession company with a 8,000<br />

ha area located at Sungai Aur, near Berbak NP; main species<br />

planted are jelutung, with some pulai).<br />

PT. PDIW Putra Duta Indah Wood (logging concession company with a<br />

concession to the west/southwest <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP<br />

PT. SDR Satia Djaya Raya (now defunct logging concession company)<br />

pulai Alstonia species ; in the swamp <strong>for</strong>ests <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP this is<br />

predominantly Alstonia pneumatophora (Apocynaceae)<br />

PUSDALKARHUTLA Pusat Pengendalian Kebakaran Hutan dan Lahan (Centre <strong>for</strong><br />

Prevention <strong>of</strong> Forest and Land Fires)<br />

ramin Gonystylus bancanus (Thymelaeaceae)<br />

rasau Pandanus helicopus (Pandanaceae)<br />

RIL Reduced Impact Logging (Malaysian system, esp. Sarawak)<br />

sere Ecological term <strong>for</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> plant communities resulting from the<br />

process <strong>of</strong> succession. Various types exist, depending on type <strong>of</strong><br />

disturbance or influence, e.g. fire sere, xerosere, hydrosere.<br />

SM Simpang Melaka<br />

SMPSF Sustainable Management <strong>of</strong> Peat Swamp Forests in Peninsular<br />

Malaysia (project)<br />

SRS Silviculture/Rehabilitation Specialist<br />

Sungai (or sungei) River<br />

TM Thematic Mapper (type <strong>of</strong> Landsat stellite image)<br />

TPTI Ind<strong>one</strong>sian selective logging process<br />

WI-IP Wetlands International – Ind<strong>one</strong>sia Programme<br />

YAPENTA Yayasan Pembangunan Tanjung Jabung (Tanjung Jabung<br />

Development Foundation)<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 5

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

Background<br />

This study is a comp<strong>one</strong>nt <strong>of</strong> the project on “Promoting the river basin and ecosystem<br />

approach <strong>for</strong> sustainable management <strong>of</strong> SE Asian lowland peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests: Case study<br />

Air Hitam Laut river basin, Jambi Province, Ind<strong>one</strong>sia” (a.k.a. Air Hitam Laut project),<br />

funded by the Netherlands Government as part <strong>of</strong> the Water <strong>for</strong> Food and Ecosystems<br />

Programme. Implementation <strong>of</strong> the Air Hitam Laut project is lead by the International<br />

Agricultural Centre (IAC) in Wageningen, the Netherlands, in cooperation with ARCADIS<br />

Euroconsult (Arnhem, the Netherlands), Alterra – Green World Research (Wageningen),<br />

Wetlands International (Wageningen and Bogor), Waterloopkundig Laboratorium<br />

(WL|Delft Hydraulics) and the Landbouw Economisch Instituut (LEI/Wageningen). In<br />

Ind<strong>one</strong>sia, the project cooperates with the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Forestry, Ministry <strong>of</strong> Environment,<br />

Ministry <strong>of</strong> Public Works, BAPPEDA (Provincial Planning Bureau), University <strong>of</strong> Jambi,<br />

Agricultural University <strong>of</strong> Bogor and the University <strong>of</strong> Sriwijaya, Palembang. Regionally,<br />

the project collaborates with the Global Environment Centre, based in Kuala Lumpur.<br />

The goal <strong>of</strong> the Air Hitam Laut project is defined as: The project will assess the nature and<br />

impact <strong>of</strong> human activities on the functioning <strong>of</strong> the greater Berbak ecosystem, analyse the hydrology<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Air Hitam Laut river, and the dependency <strong>of</strong> the coastal communities on the ecosystem health.<br />

This will provide improved understanding <strong>of</strong> the hydrological and ecological functioning <strong>of</strong> Southeast<br />

Asian lowland peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests, and contribute to an enhanced baseline <strong>for</strong> policy and decision<br />

making in relation to integrated management <strong>of</strong> peat swamp river basins in the tropics, and in<br />

particular the Berbak National Park.<br />

The bulk <strong>of</strong> the Air Hitam Laut project focuses on hydrological assessments, analysis and<br />

modeling, with smaller inputs devoted to socio-economic studies, policy analysis and<br />

awareness, and ecology-cum-peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est regeneration. The Terms <strong>of</strong> Reference <strong>for</strong><br />

the 25-day input <strong>of</strong> the peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est ecologist focuses on:<br />

Assessment <strong>of</strong> recent developments with respect to existing re<strong>for</strong>estation<br />

techniques in peatlands and their potential <strong>for</strong> improvement;<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Assessment <strong>of</strong> the requirements <strong>for</strong> re<strong>for</strong>estation interventions in Berbak NP;<br />

Recommendations on sustainable options <strong>for</strong> rehabilitating burnt and logged peat<br />

swamp <strong>for</strong>est in the mid-upper catchment <strong>of</strong> the Air Hitam Laut river basin and<br />

the centre <strong>of</strong> Berbak National Park;<br />

Support to the preparation <strong>of</strong> a peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est rehabilitation programme; and<br />

Support <strong>for</strong> the development <strong>of</strong> capacity building activities <strong>for</strong> concession holder<br />

and NP staff in re<strong>for</strong>estation techniques and peat swamp management.<br />

The peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est ecologist carried out fieldwork in Ind<strong>one</strong>sia from 30 September to 24<br />

October, <strong>of</strong> which three weeks were spent in Jambi. This output is to provide a basis <strong>for</strong><br />

practical restoration attempts by the Silviculture/Rehabilitation Specialist (Iwan Cahyo<br />

Wibisono), who will continue up until the end <strong>of</strong> the project (late 2004). The report will also<br />

provide a basis <strong>for</strong> two students <strong>of</strong> Wageningen Agricultural University (Pieter Leenman<br />

and Pieter van Eijk) and two students <strong>of</strong> Jambi University (Dian Febriyanti and Muhammad<br />

Fadli) who will carry out ecological studies on burnt peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est in Berbak in<br />

January-April 2004.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 6

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

Summary<br />

Chapter <strong>one</strong> provides an introduction to the peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia,<br />

including a brief overview <strong>of</strong> past studies, remaining area <strong>of</strong> this habitat (33 million ha, <strong>of</strong><br />

which 82% in Ind<strong>one</strong>sia), and a general description <strong>of</strong> features. It also provides an<br />

introduction to floristics and vegetation <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asian and Sumatran peat swamp<br />

<strong>for</strong>ests> It also focuses on plant species diversity, with up to 240 species in a single location,<br />

but usually in the range <strong>of</strong> 35-130 tree species occurring in a single 1-5 ha plot. A recent<br />

history <strong>of</strong> this habitat in Southeast Asia is given, indicating the rapid rate at which peat<br />

swamp <strong>for</strong>ests have disappeared due to felling, fires, and conversion to agriculture or<br />

pulpwood plantations. In 1993, only 2% <strong>of</strong> Sumatra’s <strong>for</strong>mer peat and freshwater swamp<br />

<strong>for</strong>ests was both gazetted in the Protected <strong>Are</strong>a system and remained in a good condition –<br />

this can only have declined further since then. An introduction is provided to the 185,000 ha<br />

Berbak National Park, which is the focus <strong>of</strong> this study and is located in the coastal z<strong>one</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Jambi Province, Sumatra. Berbak NP mainly consists <strong>of</strong> two habitat types – freshwater<br />

swamp <strong>for</strong>est and peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est – that extend over 60,000 hectares (32% <strong>of</strong> the park)<br />

and 110,000 hectares (59%), respectively. Large fires – mainly in the mid-1990s – have lead to<br />

significant loss <strong>of</strong> these habitats. A description is given <strong>of</strong> habitats and Park history.<br />

Chapter two focuses on the present condition <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP, split into two sections: <strong>one</strong><br />

providing an assessment based on previous studies and satellite imagery, the second based<br />

on field work carried out as part <strong>of</strong> the present study. Others report that about 17,000 ha<br />

(roughly 10%) <strong>of</strong> the Park has been affected by recent fires (esp. 1997-98). Analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

satellite imagery confirms this, but shows that significant disturbances in the Park between<br />

1983 and August 1997 created the conditions that lead to the highly destructive fires <strong>of</strong><br />

September 1997, and again in 1998. Most <strong>of</strong> these disturbances appear to be linked to illegal<br />

logging, as indicated by a pattern <strong>of</strong> clearing and thinning <strong>of</strong> canopy cover. Field work<br />

carried out in October 2003 shows that illegal logging still appears to be nothing short <strong>of</strong><br />

rampant throughout the Park: 26 illegal logging camps – most operational – were observed<br />

in the Park along the upper Air Hitam Laut river. Sawn timber was observed along the<br />

river, in camps, and being loaded from the AHL onto lorries on PDIW’s rail system, which<br />

at present is the main outlet <strong>of</strong> timber and logs being poached from the western side <strong>of</strong><br />

Berbak NP. Similarly, timber poaching was observed to be common and active along the Air<br />

Hitam Dalam.<br />

Chapter three attempts to assess the causes <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est degradation in Berbak NP.<br />

Previous analyses do not identify a single cause, but instead identify a host <strong>of</strong> contributing<br />

factors including lowering <strong>of</strong> water levels by transmigrants, fires escaping from agricultural<br />

fields and fires used by poachers, illegal logging, clearing by fishermen, unsustainable use<br />

<strong>of</strong> resources (esp. jelutung and nipa), insufficient patrolling and en<strong>for</strong>cement, unclear<br />

boundaries and (linked to the latter) conversion to agriculture. The direct cause <strong>of</strong> the 1997-<br />

98 fires is <strong>of</strong>ten reported to be ‘unknown’. Based on an analysis <strong>of</strong> satellite images and field<br />

work, however, it can be concluded that the most significant threat by far is posed by illegal<br />

logging activities in the National Park. Large-scale destructive fires that occurred at Berbak<br />

NP in 1997-98 appear to be directly linked to illegal logging that occurred in the same<br />

locations in the preceding decade. These activities largely went unnoticed/unreported, as<br />

they were being carried out in areas that were inaccessible to park staff. However, they can<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 7

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

be clearly observed on satellite images dating from this period. A likely sequence <strong>of</strong> events<br />

leading to the present level <strong>of</strong> degradation is provided, along with an assessment <strong>of</strong> whom /<br />

which companies were involved.<br />

Chapter four provides an overview <strong>of</strong> what is known about natural regeneration <strong>of</strong> peat<br />

swamp <strong>for</strong>ests in Southeast Asia in general, and Sumatra in particular. It recognizes various<br />

degradation seres, and plant species characteristic <strong>of</strong> secondary peat swamp habitats. It also<br />

provides an overview <strong>of</strong> past and ongoing attempts at peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est restoration, both<br />

in the region (notably in Thailand, but also Vietnam and Malaysia) and in Ind<strong>one</strong>sia.<br />

Attempts in Thailand were initiated more than 40 years ago and appear to be successful,<br />

while other initiatives in the region remain at a pilot stage. Various attempts at replanting<br />

degraded peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est have been carried out in and around Berbak NP, but all are<br />

small scale and can be regarded as trials only: there is no active restoration or rehabilitation<br />

programme ongoing. An exception to this is the jelutung and pulai plantation <strong>of</strong> PT. Dyera<br />

Hutan Lestari (PT. DHL). This study identifies species that have a high survival or<br />

recolonisation rate and may be considered <strong>for</strong> restoration activities at Berbak NP. These<br />

species include Alstonia pneumatophora (pulai), Combretocarpus rotundatus (tanah-tanah),<br />

Dyera lowii (jelutung), Elaeocarpus petiolatus, Eugenia spicata (gelam tikus), Ganua motleyana,<br />

Gluta wallichii (rengas), Gonystylus bancanus (ramin), Licuala paludosa (palas), Macaranga<br />

pruinosa (mahang), Mallotus muticus (perupuk), Neolamarckia cadamba (bengkal/medang<br />

keladi), Palaquium spp. (nyatoh), Pandanus helicopus (rasau), Pholidocarpus sumatranus (liran),<br />

Shorea pauciflora (meranti rawa), and Syzygium (Eugenia) cerina, (temasaman). Issues<br />

regarding species provenance, nurseries, planting regimes and timing, and tending<br />

requirements are described.<br />

Chapter five provides recommendations <strong>for</strong> which degraded areas within Berbak NP are to<br />

be targeted by the restoration programme. These include the Mid-upper catchment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Air Hitam Laut river, the central Air Hitam Laut burnt area (about 12,000 ha), and the<br />

Simpang Melaka burnt area (4,000 ha).<br />

Chapter six provides recommendations <strong>for</strong> the Project’s peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est restoration<br />

programme, focusing on species identification, site identification, the use <strong>of</strong> trial areas,<br />

where and how to establish nurseries, and how to improve the actual (ongoing) restoration<br />

programme itself. A draft budget, implementation schedule, and draft terms <strong>of</strong> reference are<br />

provided.<br />

Chapter seven provides recommendations <strong>for</strong> capacity building in re<strong>for</strong>estation techniques<br />

and peat swamp management. Because <strong>of</strong> proven lack <strong>of</strong> genuine interest, any investment in<br />

capacity building <strong>of</strong> the logging concessionaire (PT. PDIW) is considered a waste <strong>of</strong> scarce<br />

resources, better spent on other comp<strong>one</strong>nts <strong>of</strong> the Project. Training <strong>of</strong> National Park staff is<br />

proposed <strong>for</strong> i) establishing and managing the two nurseries, to produce material <strong>for</strong><br />

replanting in Berbak NP; and ii) planting techniques and managing replanted areas.<br />

Chapter eight provides conclusions drawn from the various chapters, and is followed by a<br />

list <strong>of</strong> references and appendices on: i) field work itinerary, ii) site survey results, iii) site<br />

characteristics, iv) bird observations, v) list <strong>of</strong> plant species common in burnt areas, vi) ToR<br />

<strong>for</strong> the Silviculture/Rehabilitation Specialist, and vii), a photographic summary.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 8

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The author would like to thank the following agencies and persons, without whom this<br />

study would not have been possible:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Wetlands International – Ind<strong>one</strong>sia Programme, especially Pak Dibyo, Nyoman<br />

Suryadiputra, Iwan Cahyo (Yoyok) Wibisono, Yus Rusila Noor, Anggie, Labueni<br />

S., Triana, Pak Umar and Ibu Lusi. I would particularly like to thank Yoyok <strong>for</strong> the<br />

fine arrangements in the field, and his excellent insights in peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est<br />

restoration. Thanks also to Pak Nyoman and Yoyok <strong>for</strong> their comments on the first<br />

draft <strong>of</strong> this report, Labueni <strong>for</strong> her help in arranging visits to various <strong>of</strong>fice and<br />

helping with the identification <strong>of</strong> herbarium specimens, and Pak Umar <strong>for</strong> his<br />

excellent driving skills.<br />

The field team in Jambi, especially Iwan Cahyo (Yoyok) Wibisono, Suhendra (both<br />

<strong>of</strong> Wetlands International – Ind<strong>one</strong>sia Programme) and Habibie (TN Berbak staff).<br />

Staff <strong>of</strong> Taman Nasional Berbak, especially Pak Istanto (Kepala Balai TN Berbak),<br />

Mr. H. Soemarno (Wakil Kepala TN), Habibie (<strong>for</strong> his active participation in all the<br />

field trips), Mr. Rohman Fauzi (field staff Berbak NP), Pak Aziz Sembiring, Pak<br />

Ponimon, and Pak Farit (TN) <strong>for</strong> advice and assistance.<br />

Bogor Herbarium, especially Ms Afriastini <strong>for</strong> her kind help in identifying the<br />

plant specimens collected at Berbak, and Herwint Simbolon, <strong>for</strong> discussions on<br />

regeneration plot monitoring and in<strong>for</strong>mation about peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est<br />

regeneration in general.<br />

The Center <strong>for</strong> International Forestry Research (CIFOR, Bogor), especially Dr<br />

Takeshi Toma, Dr Daniel Murdiyarso, Tini Gumartini, Yulia Siagian and Nia<br />

Sabarniati, <strong>for</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation provided about peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est regeneration, and<br />

discussions held about their research programmes. Special thanks go to Iwan<br />

Kurniawan <strong>for</strong> assisting with satellite imagery <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP, as this made it<br />

possible to analyse the events leading up to the fires <strong>of</strong> the mid-1990s.<br />

Dinas Kehutanan Jambi, especially Ir. Gatot Moeryanto (Kepala Dinas)<br />

BAPPEDA Jambi, especially Ir. Helbar, <strong>for</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> maps.<br />

PT Dyera Hutan Lestari, especially Mr. Hamri P. Rosera (Director <strong>of</strong> Production)<br />

and Mr. Bambang Handoko (Director Field Operations) <strong>for</strong> the in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

provided, and <strong>for</strong> their kind assistance and hospitality in the field.<br />

BP-DAS <strong>of</strong> Jambi, especially Ir. H. Ahriman Ahmed (head), <strong>for</strong> the lively<br />

discussion <strong>of</strong> problems associated with re<strong>for</strong>estation.<br />

PUSDALKARHUTLA, especially Ir. Joko Fajar Kiswanto (Coordinator) and Mr. O.<br />

Soeparman (technical head), <strong>for</strong> discussions on the fire management programme<br />

PT Putra Duta Indah Wood), especially Ir. Hari Subagyo and the field staff (Pak<br />

Kadri, Pak Eden S. Tanga), <strong>for</strong> logistical assistance and their hospitality in the field.<br />

Dinas Pertambangan dan Energi (Mining & Energy Service), especially Ir. Akhmad<br />

Bakhtiar Amin, Kepala Dinas, <strong>for</strong> his advice.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 9

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Wim Giesen<br />

Faizal Parish (Global Environment Center) <strong>for</strong> discussions and advice on peat<br />

swamp <strong>for</strong>est management.<br />

Dr. Yadi Setiadi, Head <strong>of</strong> Forest Biotechnology Laboratory and Environmental<br />

Biotechnology Research Center. Bogor Agriculture University <strong>for</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation on<br />

peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est regeneration trials in Sumatra.<br />

Dr. Ismail Parlan <strong>of</strong> FRIM (Forest Research Institute Malaysia), <strong>for</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

about trials on peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est restoration in Malaysia.<br />

Dr. Jack Rieley <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Life Science, University <strong>of</strong> Nottingham, <strong>for</strong> a<br />

splendid overview <strong>of</strong> recent developments in the field <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est<br />

restoration in Southeast Asia.<br />

Dr. Tanit Nuyim, Princess Sirindhorn Peat Swamp Forest Research and Nature<br />

Study Center, Sungaikolok, Narathiwat, Thailand, <strong>for</strong> his kind advice and<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation about peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est restoration activities in Thailand.<br />

Mizuki Tomita, <strong>of</strong> the Graduate School <strong>of</strong> Environment and In<strong>for</strong>mation Sciences,<br />

Yokohama National University, <strong>for</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation about Melaleuca recovery on burnt<br />

peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est.<br />

Mr. Tony Sebastian <strong>of</strong> Aonyx Environmental, Kuching, <strong>for</strong> providing in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

on peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est activities and contacts in Malaysia.<br />

Lastly, I would like to thank my colleagues on the project on “Promoting the river<br />

basin and ecosystem approach <strong>for</strong> sustainable management <strong>of</strong> SE Asian lowland<br />

peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests”, especially Ingrid Gevers, Marcel Silvius, Henk Wösten and<br />

Aljosja Hooijer.<br />

ARCADIS Euroconsult<br />

Arnhem, The Netherlands<br />

25 January 2004<br />

w.giesen@arcadis.nl<br />

www.euroconsult.nl<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 10

1.1<br />

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

CHAPTER<br />

1Introduction<br />

INTRODUCTION TO SOUTHEAST ASIAN PEAT SWAMP FORESTS<br />

1.1.1 BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO PEAT SWAMP FORESTS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA<br />

General<br />

Peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia have long been poorly studied, and our current<br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> their composition, dynamics and ecology remains incomplete in spite <strong>of</strong> a<br />

surge in studies during the past decade. For a long time, Anderson (1963, 1972, 1978) and<br />

Brünig (1973, 1990), summarised by Whitmore (1984) were the only widely known studies<br />

on this habitat. Less well known were a series <strong>of</strong> papers by Coulter (1950, 1957), Wyatt-<br />

Smith (1959, 1961) and Lee (1979) in Malaya, and by Dutch <strong>for</strong>esters (e.g. van der Laan, 1925;<br />

Bodegom, 1929; Boon, 1936; Sewandono 1937, 1938), botanists (Endert, 1932; van Steenis<br />

1938, 1957; Kostermans, 1958) and soil scientists (Polak 1933, 1941; Schophuys, 1936;<br />

Driessen, 1978; Andriesse, 1986) in Ind<strong>one</strong>sia.<br />

During the past decade-and-a-half interest in this habitat increased significantly,<br />

culminating in a series <strong>of</strong> workshops and symposiums:<br />

1987: Tropical Peat and Peatlands <strong>for</strong> Development, held in Yogyakarta, and sponsored<br />

by the International Peat Society and the Ind<strong>one</strong>sian Peat Association.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

1991: 2 nd International Symposium on Tropical Peat and Peatlands <strong>for</strong> Development, held<br />

in Kuching and published as a book in 1992.<br />

1992: Workshop on Integrated Planning and Management <strong>of</strong> Tropical Lowland Peatlands,<br />

held in Cisarua, Ind<strong>one</strong>sia, 3-8 July 1992, and published by the IUCN Wetlands<br />

Programme in 1996 (Maltby et al., 1996).<br />

1995: International Symposium on Biodiversity, Environmental Importance and<br />

Sustainability <strong>of</strong> Tropical Peat and Peatlands, held in Palangkaraya, Central<br />

Kalimantan, 4-8 September 1995, with proceedings published by Samara<br />

Publishing Ltd. (Rieley & Page, 1997).<br />

The total area <strong>of</strong> peat swamps in Southeast Asia are estimated by Rieley et al. (1996) to be<br />

about 33 million hectares, <strong>of</strong> which the vast majority in Ind<strong>one</strong>sia (82%), Papua New Guinea<br />

(8.8%) and Malaysia (8.3%), with smaller areas in the Philippines (240,000 ha), Vietnam<br />

(183,000 ha) and Thailand (65,000 ha; Nuyim, 2000). However, these figures probably<br />

represent maximum areas as vast tracts <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est have been subjected to<br />

clearing, drainage and conversion throughout the region during the past two decades.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 11

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests in Southeast Asia have developed in or near coastal plains<br />

during the past 5,000-10,000 years, either developing in fresh or brackish waters overlying<br />

marine sediments, or in depressions between rivers somewhat further inland. In these areas<br />

water tables are permanently high and peat depth may be as much as 24 metres, although<br />

depths usually range from 4-8 metres. pH’s are generally low, usually ranging from 3.0-4.5.<br />

In many areas peat domes have developed, whereby the central areas are raised and their<br />

only source <strong>of</strong> water is rainwater.<br />

According to Whitmore (1984), most <strong>of</strong> the tree families <strong>of</strong> lowland evergreen dipterocarp<br />

rain <strong>for</strong>est are found in the peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est, except <strong>for</strong> the Combretaceae, Lythraceae,<br />

Proteaceae, Styraceae and Palmae (<strong>Are</strong>caceae) 1<br />

. This habitat has few endemics, probably due<br />

to the fact that most areas are less than 11,000 years old. According to Rieley and Achmad-<br />

Shah (1996), plants found in tropical peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est are usually restricted to this type <strong>of</strong><br />

habitat. In spite <strong>of</strong> this, however, few species are endemic to the peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est <strong>of</strong> a<br />

single country. The authors list seven species, all <strong>of</strong> which are restricted to either Thailand<br />

or Malaysia. Following Wyatt-Smith (1959 and 1963), Ibrahim and Chong (1992) regard this<br />

<strong>for</strong>est as uniquely adapted to waterlogging, poor nutrients and high acidity <strong>of</strong> the soil. They<br />

add that very few <strong>of</strong> the tree species are found outside this habitat, but according to Corner<br />

(1994), floristics do not bear this out. They list 50 species <strong>for</strong> the Kuala Langat peat swamp<br />

<strong>for</strong>est in Peninsular Malaysia, but at least 38 <strong>of</strong> these occur, apparently indiscriminately, in<br />

freshwater swamp <strong>for</strong>ests <strong>of</strong> Johore (Corner, 1994). Brünig (1973) also shows that floristically<br />

there is a significant overlap between peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests and so-called heath <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

(kerangas) in Sarawak and Brunei, with 146 tree species common to both habitats, including<br />

11 <strong>of</strong> the 15 dipterocarps recorded.<br />

Tree species diversity <strong>for</strong> Southeast Asian lowland <strong>for</strong>ests vary significantly, among others<br />

depending on location, habitat and plot size. For 1.0 hectare plots, tree diversity in Malesian<br />

plots listed by Whitmore (1984) vary from 70 to more than 220 species. Compared to dry<br />

lowland rain <strong>for</strong>est, however, species diversity <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests is relatively low. In<br />

Sarawak and Brunei, a total <strong>of</strong> 1800-2300 tree species occur in dry lowland <strong>for</strong>est while a<br />

total <strong>of</strong> only 234 tree species have been recorded in peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests (Whitmore, 1984).<br />

Nevertheless, vegetation <strong>of</strong> lowland peat swamps in Southeast Asia may be diverse, with<br />

communities having up to 240 plant species (e.g. in Rieley et al., 1994; Shepherd et al., 1997).<br />

At the other end <strong>of</strong> the spectrum are species-poor communities dominated by <strong>one</strong> or only a<br />

few species, <strong>for</strong> example, the Combretocarpus rotundatus dominated central domes in<br />

Sarawak described by Whitmore (1984), or degradation seres described by Giesen (1990) in<br />

South Kalimantan. Examples <strong>of</strong> species diversity in Southeast Asian peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests:<br />

Disturbed mixed peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est in South Kalimantan: 20 tree species (range 9-<br />

51); Shorea balangeran degraded peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est: 10 tree species (range 2-14),<br />

Combretocarpus rotundatus degraded peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est: 7 tree species (range 3-12);<br />

Giesen (1990).<br />

Giesen and van Balen (1991a) noted 103 species in a rapid survey <strong>of</strong> peat swamp<br />

<strong>for</strong>ests on Pulau Padang, Riau, with tree species varying from 17 (padang or pole<br />

<strong>for</strong>est) to 37 (mixed peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est) along transects <strong>of</strong> 100m. Total species<br />

diversity ranged from 94 in the mixed peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est to 37 in the padang<br />

<strong>for</strong>est.<br />

1<br />

Apparently contradicting this is the fact that 28 palm species have been recorded in Berbak NP<br />

(Giesen, 1991), although most <strong>of</strong> these may occur in peripheral, swamp <strong>for</strong>est and riperian habitats.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 12

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

54 tree species (27 families) recorded in a 3.8 ha plot <strong>of</strong> primary peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est<br />

in Kuala Langat, Peninsular Malaysia (Shamsudin & Chong, 1992).<br />

95 tree species (35 families) recorded in a 4.5 ha plot at Sungai Karang, Peninsular<br />

Malaysia (Schilling, 1992, in Ibrahim, 1997).<br />

30 common tree species and 50 rarer tree species in 37 30x30 metre (=3.33 ha) plots<br />

in peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests <strong>of</strong> Brunei (St<strong>one</strong>man, 1997).<br />

132 tree species (39 families) recorded in a 5 ha plot <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est in Pekan,<br />

Pahang, Peninsular Malaysia (Ibrahim, 1997), with the highest diversity being in<br />

the Lauraceae (14 species), followed by the Euphorbiaceae (13), Guttiferae (12),<br />

Rubiaceae (11) and Myristicaceae (9).<br />

130 tree species recorded in a variety <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est habitats in the Sungai<br />

Sebangau region <strong>of</strong> Central Kalimantan, Ind<strong>one</strong>sia (Shepherd et al., 1997).<br />

131 plant species in all were recorded at three peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est sites in Riau,<br />

Sumatra, ranging from 68-78 spp at each 2-8 ha site (Mogea & Mansur, 2000); there<br />

were five dominant species: Calophyllum soulattri, Campnosperma coriaceum,<br />

Gonystylus macrophyllus, Palaquium hexandrum, Shorea uliginosa. Herbs were<br />

dominated by Asplenium nidus, Crinum asiaticum, Gleichenia linearis, Lygodium sp.,<br />

Nepenthese ampullaria, Nephrolepis biserrata, Nephrolepis exceltata and Scleria laevis.<br />

44 tree species were recorded by Purwaningsih and Yusuf (2000) on a 1.6 ha peat<br />

swamp <strong>for</strong>est site, 15-20 m asl, in Kluet, South Aceh, dominated by Gluta renghas,<br />

along with Shorea palembanica, Parinarium corymbosum, Sandoricum emarginatum,<br />

Garcinia celebica, Eugenia sexangulata, Horsfieldia crassifolia, Mangifera longipetiolata<br />

and Litsea gracilipes.<br />

Peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests are <strong>of</strong>ten regarded as being low in biodiversity. However, a full 20% <strong>of</strong><br />

freshwater fish species found in Peninsular Malaysia are found in streams <strong>of</strong> this habitat,<br />

and this is thought to be mainly due to the occurrence <strong>of</strong> various microhabitats (Ahmad et<br />

al., 2002). Some fish species are unique to this habitat and can be regarded as threatened due<br />

habitat loss. Although much peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est has been lost to logging and fire, it remains<br />

the dominant habitat in most <strong>of</strong> the current range <strong>of</strong> the false gavial Tomistoma schlegelii,<br />

which is found only in Sumatra, Borneo and Peninsular Malaysia and is listed as Vulnerable<br />

on the IUCN Red Data List (Bezuijden et al., 2001). It is also the preferred habitat <strong>of</strong> the hairy<br />

nosed otter Lutra sumatrana, Storm’s stork Ciconia stormi, white-winged wood-duck Cairina<br />

scutulata, grey-headed fish-eagle Haliaeetus ichthyophaga, and the largest remaining habitat<br />

<strong>for</strong> Bornean populations <strong>of</strong> orangutan Pongo pygmaeus (Meijaard, 1997).<br />

Sumatran swamp <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

The first studies on Sumatran peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests were carried out in the 1930s by the<br />

<strong>for</strong>esters van Bodegom (1929), Boon (1936) and Sewandono (1937, 1938), who mainly<br />

worked in what is now Riau province. Their papers record general observations on the<br />

ecology and management <strong>of</strong> logging concessions. Sewandono (1937) noted that <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

decreased in stature when proceeding from the periphery towards the centre <strong>of</strong> a peat<br />

dome, with species such as dipterocarps and Palaquium decreasing and Calophyllum and<br />

Tristania increasing in abundance. He also noted that central areas <strong>of</strong> islands in the<br />

Bengkalis region were characterised by an abundance <strong>of</strong> Eugenia’s, Tristania, Calophyllum<br />

species, Tetramerista glabra, Campnosperma and Shorea species, with sedges dominating the<br />

undergrowth. Most <strong>of</strong> these latter areas had stunted trees, although (according to<br />

Sewandono, 1938) there did not appear to be a link with peat depth.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 13

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

The first detailed ecological study on Sumatran peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests is that by Silvius et al.<br />

(1984) in Berbak NP (then Berbak Game Reserve). This landmark study focused on a wide<br />

range <strong>of</strong> aspects <strong>of</strong> peat swamp and freshwater swamp ecology, including soils, vegetation<br />

and fauna (see 1.2.1). Detailed studies have been also carried out in peat swamps in Padang<br />

Sugihan NP in South Sumatra and Pulau Padang in Riau by Brady (1997), who mainly<br />

focused on peat development processes and models <strong>of</strong> peat accumulation. Some rapid<br />

ecological surveys were carried out in Sumatran peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests in 1990-91 by Giesen<br />

(1991) and Giesen and van Balen (1991a, 1991b). In their overview <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est<br />

vegetation, Rieley and Achmad-Shah (1996) note that tree species common to all peat<br />

swamp <strong>for</strong>ests are (in decreasing order <strong>of</strong> abundance) Garcinia spp., Shorea spp., Palaquium<br />

spp. and Campnosperma auriculata.<br />

1.1.2 RECENT HISTORY OF SE ASIAN PEAT SWAMP FORESTS<br />

General<br />

Although large tracts <strong>of</strong> peatland remain, peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests in Southeast Asia have been<br />

reduced to a fraction <strong>of</strong> their <strong>for</strong>mer area. Braatz et al. (1992) report that by 1990, 54.6% <strong>of</strong> all<br />

wetland and marsh ecosystem had been lost in the Indo-Malayan realm – much <strong>of</strong> this<br />

habitat <strong>for</strong>merly consisted <strong>of</strong> swamp <strong>for</strong>est. With most <strong>of</strong> the remaining peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

occurring in Ind<strong>one</strong>sia and Malaysia, developments in these two countries is particularly<br />

pertinent to the conservation and sustainable use <strong>of</strong> these ecosystems.<br />

Of the 1.45 million hectares <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est remaining in Malaysia, more than 80%<br />

occurs in Sarawak. Of the 200,000 hectares remaining in Peninsular Malaysia, more than<br />

160,000 hectares is found in Pahang state, mostly in <strong>one</strong> contiguous area. Recent<br />

developments (e.g. felling <strong>of</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer Virgin Jungle Reserves) have lead to the disappearance<br />

<strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the last remaining peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests in Selangor and Johore.<br />

Ind<strong>one</strong>sian swamp <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> western Ind<strong>one</strong>sia’s 2 swamp <strong>for</strong>ests have not fared well during the past decades,<br />

and much has disappeared, either being converted <strong>for</strong> agriculture (esp. rice paddies) or tree<br />

crop estates (HTI, e.g. oil palm), or having been severely degraded and aband<strong>one</strong>d (e.g.<br />

large tracts <strong>of</strong> sedge-fern belukar). Many areas <strong>of</strong> deep peat were earmarked <strong>for</strong> conversion<br />

(inappropriately, according to Silvius & Giesen, 1996), which permitted clear-felling <strong>of</strong> vast<br />

tracts <strong>of</strong> land following a first round <strong>of</strong> selective logging (TPTI). The sale <strong>of</strong> timber and logs<br />

from clear-felled areas was usually more than sufficient <strong>for</strong> the following investment, <strong>for</strong><br />

example, in plantation crops such as Acacia or oil palm, and subsequent failure <strong>of</strong> these<br />

ventures did not result in bankruptcy <strong>of</strong> the companies involved. The Forestry Department<br />

has just completed a round <strong>of</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong> HTI estates and will cancel the concessions <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>those</strong> considered to be unviable. A large number are expected to be affected.<br />

2 Apart from Papua, where vast tracts still remain, eastern Ind<strong>one</strong>sia has only a very limited area <strong>of</strong><br />

swamp <strong>for</strong>est.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 14

FIGURE 1.1<br />

Peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests in<br />

Western Ind<strong>one</strong>sia, 1988-90<br />

(based on Giesen, 1994).<br />

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

Production <strong>for</strong>ests (HP, HPT) 3 in peat and freshwater swamp areas have on the whole not<br />

fared much better and have been poorly to very poorlymanaged by concession holders<br />

(HPHs). After a first round <strong>of</strong> selective logging by the HPH, these <strong>for</strong>ests have usually been<br />

subjected to continued rounds <strong>of</strong> illegal logging, leading to severe degradation and <strong>of</strong>ten to<br />

(repeated) fires. Once an area is severely degraded, the HPHs <strong>of</strong>ten request a change <strong>of</strong><br />

status <strong>of</strong> the area to that <strong>of</strong> HTI, after which the area is clear-felled and planted with estate<br />

crops.<br />

Ostensibly, large areas <strong>of</strong> swamp <strong>for</strong>est are protected in a number <strong>of</strong> reserves in Western<br />

Ind<strong>one</strong>sia, <strong>for</strong> example Berbak NP (Jambi), Way Kambas NP (Lampung), Tanjung Putting<br />

NP (Central Kalimantan), and Danau Sentarum NP (West Kalimantan). On the whole,<br />

protection is limited and widespread poaching <strong>of</strong> timber resources is rampant in all<br />

reserves, all <strong>of</strong> which have also suffered from fires. This used to be a problem during the<br />

Suharto era, but has increased significantly since 1998, with the advent <strong>of</strong> decentralisation.<br />

According to the head <strong>of</strong> the Forestry Service (Dinas Kehutanan) in Jambi province,<br />

poaching <strong>of</strong> timber has increased six fold since 1998.<br />

Sumatran swamp <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

According to Giesen (1993, 1994), peat swamp and freshwater swamp <strong>for</strong>ests in Sumatra<br />

<strong>for</strong>merly covered an area <strong>of</strong> 92,865 km², but by 1982-3 only two-thirds (63,790 km² or 68.7%)<br />

remained. By 1988 this had decreased to 57,506 km² (61.9% <strong>of</strong> original area), <strong>of</strong> which only<br />

8,683 km² (9.3%) could be considered primary <strong>for</strong>est. Similar figures <strong>for</strong> Jambi show that <strong>of</strong><br />

the original area <strong>of</strong> 8,813 km², only 2,604 could be considered primary <strong>for</strong>est by 1988, <strong>of</strong><br />

which most occurred in and around what is now Berbak NP 4 . By 2003, most <strong>of</strong> the logging<br />

concession companies have discontinued operations as the resource has been depleted, and<br />

the logging industry is now largely the realm <strong>of</strong> rogue companies. Peat swamp <strong>for</strong>ests –<br />

most <strong>of</strong> which had the status limited production <strong>for</strong>est (HPT) or peat protection <strong>for</strong>est<br />

(HLG) – have been severely degraded, converted (e.g. <strong>for</strong> pulp production), and have been<br />

the locus <strong>of</strong> widespread fires that have been common in lowland Sumatra since the mid-<br />

1990s.<br />

Ha (x1000)<br />

12000<br />

10000<br />

8000<br />

6000<br />

4000<br />

2000<br />

0<br />

Java<br />

Sumatra<br />

Kalimantan<br />

primary remaining<br />

degraded<br />

g<strong>one</strong><br />

3 HP = Hutan Produksi or (normal) production <strong>for</strong>est; HPT = Hutan Produksi Terbatas or limited<br />

production <strong>for</strong>est ; most peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est is included in the HPT category.<br />

4 At the time Berbak’s status was that <strong>of</strong> Wildlife Reserve.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 15

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

In 1993, 187,050 hectares <strong>of</strong> undisturbed peat and freshwater swamp <strong>for</strong>est had been<br />

incorporated into the Ind<strong>one</strong>sian Protected <strong>Are</strong>a system, <strong>of</strong> which 80% occurred in Berbak.<br />

(Giesen, 1993; Silvius & Giesen, 1996). A further 433,000 hectares <strong>of</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer peat swamp<br />

<strong>for</strong>est and freshwater swamp <strong>for</strong>est were located in gazetted reserves, but much had already<br />

been degraded or disappeared altogether. By 1993, only 10% <strong>of</strong> the <strong>for</strong>mer peat and<br />

freshwater swamp <strong>for</strong>ests occurred in Kurumutan Baru Nature Reserve (Riau), while that <strong>of</strong><br />

Padang Sugihan Wildlife Reserve (South Sumatra) and Giam-Siak Kecil Wildlife Reserve<br />

(Riau) had disappeared altogether.<br />

By 1993, only 2% <strong>of</strong> Sumatra’s <strong>for</strong>mer peat and freshwater swamp <strong>for</strong>ests was gazetted in<br />

Protected <strong>Are</strong>as and remained in a good condition. As noted above, illegal logging has<br />

increased significantly (reportedly six fold) since 1998, and as a result it is expected that very<br />

little intact swamp <strong>for</strong>est remains outside the Berbak NP area, and even that has been<br />

affected (see below). Since the early 1990s, widespread wildfires have added a new<br />

dimension to peat swamp management, and according to Tacconi (2003), a total <strong>of</strong> 308,000<br />

hectares <strong>of</strong> peat swamp and freshwater swamp <strong>for</strong>est burnt in Sumatra al<strong>one</strong> during the<br />

1997-98 fires.<br />

1.2 INTRODUCTION TO BERBAK NP<br />

1.2.1 BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE NATURAL CONDITIONS OF THE PARK<br />

The following description is mainly derived from Silvius et al. (1984), with some additions from<br />

Giesen (1991), or based on the current study.<br />

Berbak NP is located in the coastal z<strong>one</strong> <strong>of</strong> Jambi Province, Sumatra, and extends over an<br />

area <strong>of</strong> approximately 185,000 hectares (Figure 1.2). Berbak <strong>for</strong>ms part <strong>of</strong> the vast alluvial<br />

coastal plain <strong>of</strong> eastern Sumatra, that is assumed to have <strong>for</strong>med about 5,000 years BP.<br />

Evidence indicates that sea levels have dropped about two metres during the past 5,000<br />

years, with sediments – mainly supplied by the Batanghari River – accumulating along the<br />

accreting coastline. On the highly weathered sediments, peat has <strong>for</strong>med, with an average<br />

age <strong>of</strong> about 4,500 years, and in some areas with a depth <strong>of</strong> more than 20 metres (Scholtz,<br />

1983). Berbak is very flat, and at no point is the elevation more than about 15 metres.<br />

Berbak is mainly drained by the Air Hitam Laut River system and its main tributaries the<br />

Simpang Kubu and the Simpang Melaka, which lie almost entirely within the park. These<br />

are blackwater systems, draining peat domes, that have a pH <strong>of</strong> 3.5-3.9 and are naturally<br />

oligotrophic. The Benuh River, which <strong>for</strong>ms the southern boundary <strong>of</strong> the park, also drains<br />

peat dome areas and is similar to the a<strong>for</strong>ementi<strong>one</strong>d rivers. The Air Hitam Dalam River to<br />

the northwest differs from the other rivers in the park as it also receives floodwaters 5 from<br />

the Batanghari River that are markedly richer in silt and nutrients.<br />

Until the mid-1980s, Berbak mainly consists <strong>of</strong> two habitat types – freshwater swamp <strong>for</strong>est<br />

and peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est – that extend over 60,000 hectares (32% <strong>of</strong> the park) and 110,000<br />

5<br />

On 15-16 October 2003, Batanghari River waters were observed to be flowing into the Air Hitam Dalam<br />

River; these waters were coloured a milky brown, unlike the tannin/tea coloured waters <strong>of</strong> the Air<br />

Hitam Laut River.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 16

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

hectares (59%), respectively. Other habitats included riverine (

1.2.2<br />

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

At least 227 bird species have been recorded at Berbak, including nine hornbill species, and<br />

rare species such as milky stork Mycteria cinerea, white-winged wood-duck Cairina scutulata,<br />

and Storm’s stork Ciconia stormi. Mammals recorded at Berbak include Sumatran rhino<br />

Dicerorhinus sumatrensis, Malay tapir Tapirus indicus, Sumatran tiger Panthera tigris and sun<br />

bear Helarctos malayanus. Reptiles include the rare river terrapin Batagur baska, and two<br />

crocodilians, false gavial Tomistoma schlegli and estuarine crocodile Crocodylus porosus.<br />

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PARK<br />

Berbak was first gazetted as a protected area in 1935, when it was proclaimed a<br />

‘wildreservaat’ (i.e. game reserve) by a decree by the Governor General <strong>of</strong> the Netherlands-<br />

Indies on 29 October 1935. The (then) Ind<strong>one</strong>sian Directorate General <strong>of</strong> Forest Protection<br />

and Nature Conservation (PHPA) 7 began management activities in Jambi in 1972, and<br />

boundary demarcation <strong>of</strong> Berbak was completed by 1974. Nevertheless, there were still<br />

some areas <strong>of</strong> dispute at the time, including overlap with logging concessions and<br />

encroachment by Buginese settlers along the coast. Management at provincial level by<br />

PHPA is carried out via KSDA (Balai Konservasi Sumber Daya Alam, or the Natural resource<br />

Management <strong>of</strong>fice), that established a reserve headquarters in Nipah Panjang in 1975, and<br />

field <strong>of</strong>fices (‘resorts’) at Air Hitam Laut (1975), Air Hitam Dalam, Sungai Benuh and<br />

Simpang Datuk (all 1983; see Figure 1.2). Apart from these four resorts, a network <strong>of</strong> guard<br />

posts (pos jaga) were also established, notably at Simpang Melaka and Simpang Kanan.<br />

A first management plan was developed in 1991-1992 <strong>for</strong> Berbak Game Reserve as part <strong>of</strong><br />

the Sumatra Wetlands Project, executed jointly by PHPA and the Asian Wetland Bureau. It<br />

was recognised as Ind<strong>one</strong>sia’s first Ramsar wetland <strong>of</strong> international importance, on 8 April<br />

1992, and was the target <strong>of</strong> several management-oriented projects in the mid-1990s (mainly<br />

focusing on sustainable bufferz<strong>one</strong> development). Under the new ministerial decree on<br />

<strong>for</strong>estry (No. 185/Kpts-II/1997) dated 31 March 1997, Berbak’s status was upgraded to that<br />

<strong>of</strong> national park, and management handed over from KSDA to the Provincial National Park<br />

Unit (Taman Nasional) section <strong>of</strong> the Forestry Department in 1998. Taman Nasional have<br />

maintained the infrastructure established by KSDA, expanding this with several boats and<br />

replacing 90% <strong>of</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer reserve staff.<br />

7 PHPA is now the Directorate General <strong>of</strong> Nature Protection and Conservation (NPC)<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 18

FIGURE 1.2<br />

Map <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP, adapted<br />

from Silvius et al., 1984.<br />

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 19

2.1<br />

TABLE 2.1<br />

Monthly rainfall figures<br />

recorded at Kenten,<br />

Palembang<br />

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

2Assessment <strong>of</strong> present<br />

condition <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP<br />

CHAPTER<br />

CONDITION OF BERBAK NP AS REPORTED BY OTHERS<br />

Management Plan <strong>for</strong> Berbak NP<br />

Wetlands International – Ind<strong>one</strong>sia Programme produced a management plan <strong>for</strong> Berbak<br />

NP (WI-IP, 2000). This plan includes sections on degradation <strong>of</strong> the park due to fires, and<br />

refers to two major fires in Berbak NP in the 1990s, namely in 1994 and 1997. It goes on to<br />

state that these <strong>for</strong>est fires took place during a prolonged dry season related to the El-Niño<br />

phenomenon (Table 2.1). Surveys were carried out in 1998 in order to assess impacts,<br />

concluding that an estimated 18,000 ha (or about 11% <strong>of</strong> the park) <strong>of</strong> peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est<br />

burnt during the 1997 fires in three isolated locations inside the park.<br />

YEAR<br />

JAN FEB MAR APR<br />

Monthly Total (mm)<br />

MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC<br />

1996 244 292 304 231 53 271 173 99 126 303 314 294<br />

1997 139 292 319 336 215 65 6 4 0 6 124 330<br />

1998 207 165 402 282 177 137 181 119 213 137 310 390<br />

48 year<br />

average<br />

(1951-98)<br />

240 247 322 283 181 136 125 113 143 197 303 331<br />

Source: Anderson et al. (1999)<br />

Forest Fire Prevention and Control Project<br />

Anderson and Bowen (2000) recognise seven major fire z<strong>one</strong>s in Sumatra, <strong>of</strong> which <strong>one</strong> – the<br />

Batanghari River Wetlands and Berbak NP – encompasses the Air Hitam Laut peatlands.<br />

Around 17,000 ha or about 10% <strong>of</strong> the park was destroyed by fires in 1997. The grassland<br />

nucleus caused by the 1997 fires coupled with the boundary felling and illegal logging has<br />

opened up the whole park to destruction by fire in the next El Niño year. Based on imagery<br />

from September 2000. at least 10% <strong>of</strong> the Park has been damaged by fire.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 20

FIGURE 2.1<br />

AREAS BURNT IN THE 1997-<br />

1998 EL NIÑO YEAR<br />

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

Conservation In<strong>for</strong>mation Forum (WARSI) Ind<strong>one</strong>sia<br />

According to the Ind<strong>one</strong>sian Conservation in<strong>for</strong>mation Forum (WARSI; www.warsi.or.id),<br />

3,406 hectares had been cleared and burned to the north <strong>of</strong> Berbak NP by the 1 st <strong>of</strong> May 1998,<br />

after the 1997 El Niño. At the same time, two large fires had significantly affected the core <strong>of</strong><br />

the park: <strong>one</strong> extending over 12,669 hectares along both sides <strong>of</strong> the Air Hitam Laut,<br />

upstream <strong>of</strong> the Simpang Kubu, the second covering 4,133 hectares on both banks <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Simpang Melaka River (see Figure 2.1, adapted from the WARSI website).<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

30 May 1997<br />

(adapted from the WARSI website; www.warsi.or.id)<br />

Assessment by Wetlands International<br />

<br />

1 May 1998<br />

Wetlands International – Ind<strong>one</strong>sia Programme carried out a DGIS 8<br />

-funded study on the<br />

burnt areas in 2002 (WI-IP, 2002). According to the report on this study, “fire has changed<br />

the properties <strong>of</strong> the peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est ecosystem in Berbak. Closed canopy <strong>of</strong> tall trees<br />

with lower vegetation on the <strong>for</strong>est floor has been replaced by a mosaic <strong>of</strong> open patches <strong>of</strong><br />

burnt stands dominated by pi<strong>one</strong>er species consisting <strong>of</strong> grass and shrubs. Regeneration <strong>of</strong><br />

pi<strong>one</strong>er species has been detected by the emergence <strong>of</strong> several typical pi<strong>one</strong>er species in<br />

peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est such as the occurrence <strong>of</strong> Macaranga. Repeated and frequent fire events<br />

will eventually alter the ecosystem in the direction <strong>of</strong> a grass swamp ecosystem or open<br />

secondary swamp <strong>for</strong>est.” It goes on to describe the large, central burnt area along the Air<br />

Hitam Laut, which “ was estimated at around 12,000 ha. It was reported that during the<br />

rainy season it was covered by water which made it look like a large open lake, and that<br />

during the dry season some fire resistant plant species with a height <strong>of</strong> almost 4 metres<br />

(locally known as “mahang”; = Macaranga) appeared.” According to Lubis (2002), <strong>of</strong> the<br />

294,314 ha <strong>of</strong> peatland in Berbak and the surrounding area (i.e. the bufferz<strong>one</strong>), 211,024 <strong>of</strong><br />

peat swamp <strong>for</strong>est is still left, representing a loss <strong>of</strong> about 28%.<br />

8 Netherlands Directorate General <strong>of</strong> Foreign Aid.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 21

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

2.2 ASSESSMENT OF CONDITION OF BERBAK NP BASED ON SATELLITE IMAGERY<br />

FIGURE 2.2<br />

Satellite images <strong>of</strong> Berbak<br />

NP, showing changes from<br />

1983-2002.<br />

In order to assess development within and around Berbak over the past two decades, a time<br />

series <strong>of</strong> Landsat satellite images from 1983-2002 were obtained from the Landsat website<br />

(http//www.landsat.org) as quick looks, and as processed images from CIFOR in Bogor.<br />

These were assessed <strong>for</strong> changes in land use/land cover in and around Berbak NP. From<br />

these, the following emerges (see Figure 2.2).<br />

Images Date & notes<br />

16 April 1983 (fig. 2.2a)<br />

Clouds obscure much, but<br />

<strong>one</strong> may conclude that<br />

Berbak NP appears to be<br />

(largely) intact.<br />

9 June 1989 (fig. 2.2b)<br />

The large central part <strong>of</strong><br />

Berbak NP along the Air<br />

Hitam Laut has a paler<br />

appearance, indicating a<br />

difference compared to<br />

adjacent areas (darker<br />

green) and possible<br />

disturbance (see Figure<br />

2.3)<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 22

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

16 May 1992 (fig. 2.2c)<br />

Apparent are some small<br />

fires (red) along the Air<br />

Hitam Laut, upstream <strong>of</strong><br />

the large area burnt in<br />

1997/1998, but well<br />

within the park. The<br />

image is too unclear to<br />

conclusively assess<br />

disturbance along the<br />

central AHL area.<br />

18 August 1997 (fig.<br />

2.2d)<br />

This image was taken just<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e the major 1997 El<br />

Niño fires, which started<br />

in September. Note along<br />

AHL: small fires (red),<br />

pale green vegetation<br />

(possibly indicating<br />

secondary vegetation<br />

and/or clearing); and a<br />

rectangle <strong>of</strong> clear-felling<br />

at Simpang Kubu. For<br />

detail <strong>of</strong> latter see fig. 2.4.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 23

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

1 May 1998 (fig. 2.2e)<br />

Widespread fire damage<br />

is visible on the 1998<br />

image (red), showing that<br />

a large central area along<br />

AHL has burnt again in<br />

1998, along with smaller<br />

patches along the<br />

upstream section <strong>of</strong> AHL,<br />

a large area along the<br />

Simpang Melaka, the<br />

upper part <strong>of</strong> the Air<br />

Hitam Dalam, and the<br />

downstream part <strong>of</strong> AHL<br />

close to AHL village.<br />

Black line indicates<br />

approximate boundary <strong>of</strong><br />

Berbak NP.<br />

1 September 1999<br />

(fig. 2.2f)<br />

By 1999, secondary<br />

vegetation had developed<br />

on most <strong>of</strong> the large burnt<br />

areas in Berbak (pale<br />

green), but new fires (red)<br />

had again affected 10-30%<br />

<strong>of</strong> the disturbed areas<br />

along the AHL and<br />

Simpang Melaka. Note<br />

the ongoing fire at Sungai<br />

Aur (N. <strong>of</strong> Batanghari).<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 24

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

8 August 2002 (fig. 2.2g)<br />

Although the image is<br />

somewhat obscured by<br />

clouds, the same pattern<br />

as in 1999 emerges, with<br />

some central areas in<br />

Berbak being subjected to<br />

recent (2002) burning<br />

(red), and the rest covered<br />

with secondary vegetation<br />

(pale green).<br />

It would appear that between 1983 and August 1997 (fig.’s 2.2a and 2.2d), significant<br />

disturbances occurred within the park, leading up to the highly destructive fires <strong>of</strong><br />

September 1997, and again in 1998. The 1989 image (fig. 2.2b) already shows what appears<br />

to be a paler vegetation, but this is not visible on the 1992 image (fig. 2.2c), which is less<br />

clear. An enlarged black-and-white detail <strong>of</strong> the 1992 image (16 May) adapted from<br />

www.eelaart.com is provided in Figure 2.3. This image – on which the approximate area<br />

burnt in 1997 is indicated by means <strong>of</strong> a thick black line – clearly shows that the area that<br />

was later burnt had a finer grained vegetation, indicating smaller canopy size, than the<br />

surrounding vegetation. It also shows some open areas directly along the AHL, and used<br />

logging trails to the west <strong>of</strong> the AHL.<br />

Most peat swamps have evidence <strong>of</strong> concentric <strong>for</strong>est z<strong>one</strong>s, <strong>of</strong> which the innermost in<br />

extreme cases comprise stunted trees commonly <strong>of</strong> markedly xeromorphic aspect<br />

(Whitmore, 1984). Sewandono (1938) discovered a similar phenomenon when studying the<br />

peat swamps <strong>of</strong> Bengkalis Island, <strong>of</strong>f the coast <strong>of</strong> Riau. He found that when heading inland<br />

from the coast, the cover <strong>of</strong> herbaceous terrestrial species and small palms increased,<br />

including species such as Zingiberaceae, Cyperaceae, Araceae, Eleiodoxa (Salacca) conferta,<br />

Licuala, some rattans, Cyrtostachys lakka and Pandanus. Where trees had been felled there was<br />

an abundance <strong>of</strong> Cyperaceae and ferns. In the middle <strong>of</strong> the islands he discovered many<br />

dead and dying trees, that were <strong>of</strong>ten diminutive in size, and a dense undergrowth mainly<br />

consisting <strong>of</strong> sedges. Sewandono recorded no evidence <strong>of</strong> fires, nor did the phenomenon<br />

appear to be linked with increasing peat depth. Since then, studies have indicated that<br />

extreme nutrient deficiency in central parts <strong>of</strong> ombrogenous peat domes can lead to such<br />

patterns (Whitmore, 1984). However, as this central part <strong>of</strong> the AHL straddles the river<br />

system this seems an unlikely explanation, and a more logical explanation <strong>for</strong> the observed<br />

pattern is that illegal logging had degraded the central AHL <strong>for</strong>ests already by 1992, and<br />

that logs were being transported out <strong>of</strong> the National Park via the logging trail.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 25

FIGURE 2.3<br />

Disturbances along the<br />

central Air Hitam Laut,<br />

16 May 1992.<br />

FIGURE 2.4<br />

Disturbances along central<br />

Air Hitam Laut area,<br />

18 August 1997.<br />

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

The image dating from 18 August 1997 (fig. 2.2d) – taken just be<strong>for</strong>e the catastrophic fires,<br />

shows some signs <strong>of</strong> disturbance that may have been the direct cause. An enlargement <strong>of</strong><br />

this image (fig.2.4) shows that some smaller fires had already occurred along the Air Hitam<br />

Laut between Simpang “T” and Simpang Kubu, and that a rectangle <strong>of</strong> 120-150 hectares had<br />

been cleared at Simpang Kubu. These are clear signs <strong>of</strong> disturbance and human activities in<br />

the park’s core area, and are likely to be directly responsible <strong>for</strong> the occurrence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

catastrophic fires. The cleared rectangle is already showing signs <strong>of</strong> revegetation (most <strong>of</strong> it<br />

is pale green in colour), and this may have been cleared 1-2 seasons be<strong>for</strong>e August 1997.<br />

Final Draft ARCADIS 26

CAUSES OF PEAT SWAMP FOREST DEGRADATION IN BERBAK NP, INDONESIA, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESTORATION<br />

2.3 FIELDWORK AND OBSERVATIONS OF STATE OF HABITATS AT BERBAK NP<br />

2.3.1 FIELDWORK METHODOLOGY<br />