Pacifastacus leniusculus - NOBANIS

Pacifastacus leniusculus - NOBANIS

Pacifastacus leniusculus - NOBANIS

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>NOBANIS</strong> - Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet<br />

<strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong><br />

Authors of this fact sheet:<br />

Stein I. Johnsen, Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), Fakkelgården, NO-2624 Lillehammer, Norway; +47<br />

73801628; stein.ivar.johnsen@nina.no<br />

Trond Taugbøl, Glommen’s and Laagen’s Water Management Association, P.O.Box 1209 Skurva, NO-2605<br />

Lillehammer, Norway; +47 93466712; tt@glb.no<br />

Bibliographical reference – how to cite this fact sheet:<br />

Johnsen, S.I. and Taugbøl, T. (2010): <strong>NOBANIS</strong> – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet – <strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong>. –<br />

From: Online Database of the European Network on Invasive Alien Species – <strong>NOBANIS</strong> www.nobanis.org, Date of<br />

access x/x/201x.<br />

Species description<br />

Scientific names: <strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong> (Dana, 1852), Astacidae.<br />

Synonyms: no common synonyms used.<br />

Common names: signal crayfish (GB), rak signální (CZ), signalkrebs (DK), Signalkrebs (DE),<br />

signaalvähk (EE), täplärapu (FI), žymėtasis vėžys (LT), signālvēzis (LV), Californische rivierkreeft<br />

(NL), signalkreps (NO), rak sygnałowy (PL), сигнальный рак (RU), signalkräfta (SE).<br />

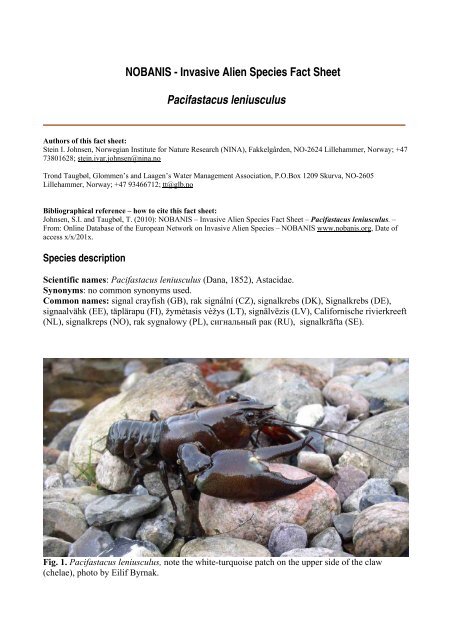

Fig. 1. <strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong>, note the white-turquoise patch on the upper side of the claw<br />

(chelae), photo by Eilif Byrnak.

Species identification<br />

The signal crayfish is similar to and can be confused with the noble crayfish (Astacus astacus)<br />

which is native to parts of the region. The signal crayfish is distinguished from the noble crayfish,<br />

both as juvenile and adult, by the more smooth nature of the chelae and the lack of a row of spines<br />

on the shoulders of carapace behind cervical groove. The white-turquoise patch on the upper side of<br />

the chelae is also unique to the adult signal crayfish (Fiskeriverket/Naturvårdsverket 2005, Lewis<br />

2002, Pöckl et al. 2006).<br />

Native range<br />

The native range of the signal crayfish is the northwestern USA and southwestern Canada where it<br />

occurs from British Columbia in the north, central California in the south, and Utah in the east<br />

(Lewis 2002).<br />

Alien distribution<br />

History of introduction and geographical spread<br />

In 1960, a small batch of signal crayfish was introduced to Sweden from California, USA, in an<br />

attempt to find a species which could replace the populations of the indigenous noble crayfish,<br />

which was severely depleted by the crayfish plague from 1907 onwards<br />

(Fiskeriverket/Naturvårdsverket 1998). The signal crayfish was considered to occupy the same<br />

ecological niche and presumed to be able to restore the recreational and commercial important<br />

crayfish fishery in the plague affected areas. The fact that it was also a carrier of crayfish plague<br />

was unknown at the time (Unestam 1972). Trials were successful and in 1967-69, a large number of<br />

signal crayfish were imported from USA and introduced into Swedish and Finnish waters (Lowery<br />

and Holdich 1988, Westman 1995). These were followed by further secondary introductions,<br />

including large numbers of domestic hatchery-reared juveniles. Further introductions, especially of<br />

juveniles from Sweden, were made to many European countries (Lowery and Holdich 1988). The<br />

signal crayfish is at present most established in Sweden where it occurs in approximately 4000<br />

localities (Edsman and Schröder 2009). An increasing number of signal crayfish introductions have<br />

taken place during the last 30 years in Denmark and this illegal practice still goes on. The crayfish<br />

has been released in many small lakes, wherefrom it has spread to a number of the larger river<br />

system on Zealand and in Jutland. In the summer 2010 it was found in coastal waters in the Danish<br />

part of the Baltic Sea as well (Eilif Byrnak, pers. comm.; Søren Berg, pers. comm..). In Austria,<br />

2000 signal crayfish were imported in summer 1970 from California and released in several<br />

provinces. Today, the species is present in all provinces, widely distributed, particularly in the<br />

eastern provinces, and locally abundant. The crayfish was introduced to Czech Republic in 1980<br />

from Sweden for commercial production. Until 2006, the signal crayfish was recorded in 24<br />

European countries/regions (Souty-Grosset et al. 2006). Signal crayfish was recorded in Norway in<br />

2006 (Johnsen et al. 2007), but this population is now most likely eradicated with chemicals<br />

(Sandodden and Johnsen 2010). However, signal crayfish was recorded in a larger watercourse in<br />

south-eastern Norway in 2008 (Johnsen and Vrålstad 2009). Records of signal crayfish in Norway,<br />

Slovakia (Maguire et al. 2008) and Croatia (Petrusek and Petruskova 2007) extends the list from<br />

2006 (Souty-Grosset et al. 2006) to 27 European countries/regions (Holdich et al. 2009). This<br />

makes the signal crayfish the most widely spread alien freshwater crayfish species in Europe<br />

(Souty-Grosset et al. 2006, Holdich et al. 2009). In the Nordic-Baltic region it is found/established<br />

in all countries except Russia (nor in Iceland, Greenland and Faroe Islands where no freshwater<br />

crayfish species occur). In 2008 the first specimen was found in Estonia (Hurt and Kivistik 2009).<br />

2

Fig. 2. Present distribution of signal crayfish (<strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong>) in Europe. © Publications<br />

Scientifique MNHN, Paris, 2006. (After Souty-Grosset et al. 2006). The records of signal crayfish<br />

in Norway (Johnsen and Vrålstad 2009, Slovakia (Maguire et al. 2008) and Croatia (Petrusek and<br />

Petruskova 2007), Estonia (Hurt and Kivistik 2009) and Jutland, Denmark (E. Byrnak pers. comm.)<br />

are not represented in the map.<br />

Pathways of introduction<br />

The most common pathway of introduction into natural waters is stocking by humans. In the 1970-<br />

80s the stocking policy in the region was liberal, and the signal crayfish was introduced legally into<br />

a large number of natural waters. From the late 1980s onwards, the introduction of the signal<br />

crayfish into new areas was restricted by the environmental authorities due to the threat it posed to<br />

the indigenous, red-listed noble crayfish (Troschel and Dehus 1993, Skurdal et al. 1999, Edsman<br />

2004). However, the distribution of the signal crayfish is still rapidly increasing, including more and<br />

more watercourses. The crayfish can spread by natural migration only within a watercourse,<br />

between migration barriers. Most of the current spread is therefore due to illegal introductions by<br />

humans.<br />

Alien status in region<br />

The signal crayfish has been introduced to all countries in the region, except Russia and the North<br />

Atlantic Islands (see table 1). In Estonia, one specimen of signal crayfish was found in R.<br />

Mustjõgi (northern Estonia) in 2008. In 2009, a bigger survey was carried out, no alien crayfish was<br />

found, but no native crayfish was found where the alien crayfish had been found previously. Thus,<br />

the signal crayfish might have been the carrier of crayfish plague (Hurt and Kivistik 2009). It is<br />

very common in Sweden and Finland, common in Germany, Denmark and Austria and found in a<br />

more limited number of localities in Poland, Lithuania and Latvia (Souty-Grosset et al. 2006). In<br />

Norway, signal crayfish is now only confirmed to exist in one locality (Johnsen and Vrålstad 2009).<br />

3

Country Not Not Rare Local Common Very<br />

found established<br />

common<br />

Austria<br />

Belgium<br />

X<br />

Czech republic X<br />

Denmark X<br />

Estonia X<br />

European part of Russia X<br />

Finland X<br />

Faroe Islands X<br />

Germany X<br />

Greenland X<br />

Iceland X<br />

Ireland X<br />

Latvia X<br />

Lithuania X<br />

Netherlands X<br />

Norway X<br />

Poland<br />

Slovakia<br />

X<br />

Sweden X<br />

Not<br />

known<br />

Table 1. The frequency and establishment of <strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong>, please refer also to the<br />

information provided for this species at www.nobanis.org/search.asp. Legend for this table: Not<br />

found –The species is not found in the country; Not established - The species has not formed selfreproducing<br />

populations (but is found as a casual or incidental species); Rare - Few sites where it is<br />

found in the country; Local - Locally abundant, many individuals in some areas of the country;<br />

Common - Many sites in the country; Very common - Many sites and many individuals; Not<br />

known – No information was available.<br />

Ecology<br />

Habitat description<br />

The native habitat of the signal crayfish ranges from small streams to large rivers, and lakes from<br />

the coastal to the sub-alpine regions. Signal crayfish can also survive in brackish water (Holdich et<br />

al. 1997). The distribution of the signal crayfish in Europe comprises the same range of habitats<br />

(Souty-Grosset et al. 2006).<br />

Reproduction and life cycle<br />

The signal crayfish has a typical life cycle of a member of the crayfish family Astacidae (Lewis<br />

2002). Mating and egglaying occurs during autumn, mainly in October. Egg numbers usually range<br />

from 200 to 400. After egg laying the female carry the eggs under the tail until hatching. Hatching<br />

time varies greatly depending on temperature, and in natural populations it may occur from late<br />

March to the end of July. The eggs hatch into miniature crayfish that stay with the mother for three<br />

stages (two moults). In the third stage the juvenile crayfish gradually become more and more<br />

independent of the mother, adopting a solitary life. Size at maturity is usually 6-9 cm total-length<br />

(from tip of head to edge of tail-fan) at an age of 2-3 years. Estimates of survivorship to age 2 vary<br />

from 10-52%, being dependent on both abiotic and biotic factors. Competition and cannibalism can<br />

4

greatly affect survival in dense populations. Maximum age and size are reported to be approx. 20<br />

years and 16-18 cm, but such sizes are very seldom.<br />

Dispersal and spread<br />

Humans are the overall most important vector for dispersal and spread (see above) of the signal<br />

crayfish. Due to fisheries in natural waters in most regions where it occurs, signal crayfish are easily<br />

accessible as stocking material. Within the watercourse the signal crayfish can spread by own<br />

migration. Upstream migration rates of more than 1 km per year are reported from rivers in Finland<br />

and England. Downstream spread can be faster (Westman and Nylund 1979, Guan and Wiles<br />

1997a, Peay and Rogers 1999). There are also indications that the signal crayfish may pass dams<br />

and waterfalls by walking on dry land (Hiley 2003). Probably this behaviour is triggered by high<br />

density or other unfavourable conditions. Normally, the crayfish would not leave the water and<br />

expose itself to great predation risk on land, but at least this shows its potential for self dispersal.<br />

Impact<br />

Affected habitats and indigenous organisms<br />

The signal crayfish occupies the same ecological niche as the indigenous noble crayfish. It occurs<br />

mainly in localities previously inhabited by these species, and maintains in general the same effects<br />

on natural habitats. It is considered to be a non-burrowing species in North America, but in Europe<br />

it constructs burrows in river and lake banks (Holdich and Reeve 1991), similar to the noble<br />

crayfish. As an opportunistic polytrophic feeder it also consumes detritus and thereby plays an<br />

important role in the degradation and mineralization of dead organic matter. It may exert a<br />

significant grazing pressure on macrophytes, aquatic insects, snails, benthic fishes and amphibian<br />

larvae. Several studies indicate that signal crayfish have a stronger impact on the food web structure<br />

than the indigenous noble crayfish (Guan and Wiles 1997b, Nyström 1999, 2002 and references<br />

herein).<br />

The most severe effect of the signal crayfish is the extermination of the noble crayfish, caused by<br />

the transmission of the crayfish plague (another invasive species) (Alderman 1997). Indigenous<br />

European crayfish species have no resistance to against this disease and experience total mortality.<br />

American crayfish species on the other hand have co-evolved with the crayfish plague and<br />

developed defence systems making them a natural host for and carrier of this parasitic disease<br />

(Unestam 1972, Evans and Edgerton 2002). Most, if not all, signal crayfish are infected by the<br />

crayfish plague. Thus, if a signal crayfish population is established in a watercourse, the crayfish<br />

plague is also established, and there is no possibility for the noble crayfish to co-exist. For this<br />

reason, the spread of signal crayfish is the most serious threat to the indigenous noble crayfish.<br />

Genetic effects<br />

No hybrids with other crayfish species have been reported. Signal crayfish can mate with noble<br />

crayfish, but the eggs are not fertile.<br />

Human health effects<br />

No human health effects have been reported, although allergies towards shellfish may occur.<br />

Economic and societal effects (positive/negative)<br />

In many countries in the region, especially Sweden and Finland, the signal crayfish populations<br />

support a large, commercially and recreationally important, fishery (Ackefors 1999). In Europe as a<br />

whole, a total of 355 tonnes of signal crayfish was estimated from capture fisheries in 1994<br />

5

(Ackefors 1998). This level has increased considerably, and in 2001 the Swedish catch was<br />

estimated to 1200 tonnes. In recent years, however, levels have dropped for unknown reasons.<br />

Viruses in combination with a chronic plague infection have been suspected as a possible reason<br />

(Söderhäll 2004). The amount of cultured amount of signal crayfish in Sweden was estimated to 42<br />

tonnes in 1996 (Ackefors 1998).<br />

The most serious negative effect of the signal crayfish is the extermination of the indigenous noble<br />

crayfish, due to the uncontrolled spread of the signal crayfish to more and more watercourses. The<br />

noble crayfish has great sociocultural/-economic traditions in the region (Swahn 2004) and is more<br />

valuable than the signal crayfish, also from the pure economic point of view. First and foremost<br />

because of the uncontrolled spread of signal crayfish, the noble crayfish is recognized as a<br />

threatened species included in the international Red List, the Bern Convention and EU’s Habitat<br />

Directive.<br />

Management approaches<br />

Prevention methods<br />

Preventing the further introduction of signal crayfish to new water bodies by humans is the greatest<br />

management challenge (for efforts, see below). In most countries in the region the introduction of<br />

live non-indigenous crayfish species, like the signal crayfish, is not permitted (Skurdal et al. 1999).<br />

In Latvia the import of live crayfish is allowed, only a veterinary certificate is needed (Arens and<br />

Taugbøl 2005). In all countries stocking of live crayfish in natural waters requires permission from<br />

the authorities. The lack of effective control and enforcement is, however, a problem.<br />

Eradication, control and monitoring efforts<br />

When the signal crayfish is established in a water body there is no practical way of eradication,<br />

except perhaps in very small, enclosed waterbodies where insecticides or other chemicals might be<br />

applied (Sandodden and Johnsen 2010). Extensive trapping may reduce population density and slow<br />

down the speed at which it spreads naturally, but it is not an effective control method. There is<br />

important research into pheromone trapping of male signal crayfish (Stebbing et al. 2004, Stebbing<br />

et al. 2005), this method could become in the future be used as a control and eradication method.<br />

Monitoring of the distribution and identifying new populations by test-fishing provide important<br />

information necessary in a management strategy. Monitoring of crayfish distribution and occurrence<br />

takes place in several countries in the region and reveals that illegal signal crayfish introductions<br />

occur to a large extent and is the major reason for further spread.<br />

Information and awareness<br />

The key factor to prevent further spread of the signal crayfish is information about the negative<br />

effects. It is imperative to convince landowners/fishermen that the indigenous noble crayfish is the<br />

best alternative for crayfish harvest. With live signal crayfish easily accessible from natural waters<br />

not far away, it is impossible to prevent (illegal) stocking if local people want to do so. Information<br />

campaigns, including folders/brochures, media contact and education in schools are important.<br />

Likewise concrete projects aimed at conservation and sustainable use of noble crayfish and the<br />

prevention of further spread of signal crayfish, through information and involvement of relevant<br />

interest groups. The so-called “Astacus”-project, an inter-regional collaboration project between<br />

Norway and Sweden, is an example of such a project (www.astacus.org).<br />

6

Knowledge and research<br />

Several research topics have been carried out on the signal crayfish in the region, especially in<br />

Sweden and Finland. Prevalent topics are on its ecology, immunology, behaviour, population<br />

biology and environmental impact (see Nyström 1999, 2002, Söderhäll and Söderhäll 2002 and<br />

references herein). There has also been some research into improving methods for its culture.<br />

Recommendations or comments from experts and local communities<br />

Signal crayfish should be managed as a valuable resource for recreational and commercial fishery in<br />

areas where it is established (Ackefors 1999, Taugbøl and Skurdal 1999). In other areas where the<br />

noble crayfish still has a chance to survive, the great values of this species should be emphasized,<br />

and it should be made clear to all stakeholders that the spread of signal crayfish to these areas is a<br />

tragedy to nature and to the socioeconomic/-cultural values the noble crayfish represents. In<br />

addition it is an environmental crime.<br />

Furthermore, in the light of decreasing catches and numerous collapses of signal crayfish<br />

populations in recent years, there is no guarantee that stocking of signal crayfish will give a<br />

harvestable population in the long run.<br />

References and other resources<br />

Contact persons<br />

Lennart Edsman (SE) Swedish Board of Fisheries, Freshwater Laboratory, Stångholmsvägen 2, SE-<br />

178 93 Drottningholm, Sweden; Phone: + 46 8-699 06 00, Fax: +46 8-699 06 50; E-mail:<br />

Lennart.Edsman@fiskeriverket.se<br />

Stein I. Johnsen (NO) Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Fakkelgaarden, NO-2624<br />

Lillehammer, Norway; Phone: +47 73801628; E-mail: stein.ivar.johnsen@nina.no<br />

Stefan Nehring (DE) Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, Konstantinstrasse 110, D-53179<br />

Bonn; Phone: +49-228-84911444; E-mail: stefan.nehring@bfn.de<br />

Eilif Byrnak (DK) Natur and Miljø, Vestsjællands Amt, Alleen 15, DK-4180 Sorø; Denmark<br />

Phone: +45 57872829; E-mail: eby@vestamt.dk<br />

Gudni Gudbergsson (IS) Institute of Freshwater Fisheries, Vagnhofdi 7, IS-110 Reykjavik, Iceland;<br />

Phone: +354 5676400; E-mail: gudni.gudbergsson@veidimal.is<br />

Augusts Arens (LV) Latvian Crayfish and Fish Farmers' Association, 7-6 Alberta St., Riga LV-<br />

1010, Latvia; Phone/fax: +371-7-336-005; E-mail: earens@latnet.lv<br />

Przemyslaw Smietana (PL) University of Szczecin, Department of Ecology, ul. Waska 13, PL-71-412<br />

Szczecin, Poland; E-mail: leptosp@univ.szczecin.pl<br />

Margo Hurt (EE) Department of Fishery, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Krutzwaldi 48, EE-<br />

51006 Tartu, Estonia; Phone: + 372 731 3481; E-mail: margo.hurt@emu.ee<br />

Ari Mannonen(FI) Crayfish Innovation Center, Päijänne-Institute, Koulutuskeskus Salpaus,<br />

Laurellintie 55, FI-17320 Asikkala, Finland; Phone: +358 40 7082524; E-mail:<br />

raputietokeskus@jippii.fi<br />

7

Links<br />

The International Association of Astacology (IAA)<br />

Global Invasive Species Data Base - <strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong> (ISSG - Invasive Species Specialist<br />

Group)<br />

References<br />

Ackefors, H. 1998. The culture and capture crayfish fisheries in Europe. World Aquaculture 29: 12-24, 64-67.<br />

Ackefors, H. 1999. The positive effects of established crayfish introductions in Europe, in: Gherardi, F. and Holdich, D.<br />

M. (Eds), Crayfish in Europe as alien species. How to make the best of a bad situation. A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam:<br />

49-61.<br />

Alderman, D.J. 1997. History of the spread of crayfish plague in Europe, in: Crustaceans: Bacterial and fungal<br />

diseasaes. QIE Scientific and Technical Review 15: 15-23.<br />

Arens, A. and Taugbøl, T. 2005. Status of freshwater crayfish in Latvia. Bulletin Français de la Pêche et de la<br />

Pisciculture (376-377): 519-528.<br />

Edsman, L. 2004. – The Swedish story about import of live crayfish. Bulletin Français de la Pêche et de la Pisciculture<br />

(372-373): 281-288.<br />

Edsman L. and Schröder S. 2009. Åtgärdsprogram för Flodkräfta 2008–2013 (Astacus astacus),<br />

Fiskerivertet och Naturvårdsverket, Rap. 5955, 67 p.<br />

Evans L. H. and Edgerton B. F. 2002. – Pathogens, parasites and commensals, in Holdich D. M. (Ed.), Biology of<br />

freshwater crayfish. Blackwell Science, Oxford: 377-438.<br />

Fiskeriverket/Naturvårdsverket 1998. Åtgärdsprogram för bevarande av flodkräfta.<br />

Fiskeriverket/Naturvårdsverket 2005. Information folder. Web-version<br />

Guan, R-Z. and Wiles, P.R. 1997a. The home range of signal crayfish in a British lowland river. Freshwater Forum 8:<br />

45-54.<br />

Guan, R.-Z. and Wiles, P.R. 1997b. Ecological impact of introduced crayfish on benthic fishes in a British lowland<br />

river. Conservation Biology 11: 641-647.<br />

Hiley, P.D. 2003. The slow quiet invasion of signal crayfish (<strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong>) in England – prospects for the<br />

white-clawed crayfish (Austropotamobius pallipes). Pp. 127-138 in: Holdich, D.M. and Sibley, P.J. (eds.)<br />

Management and Conservation of Crayfish. Proceedings of a conference held on 7 th November, 2002. Environment<br />

Agency, Bristol, 217 pp.<br />

Holdich, D. M, Harlioglu, M. M. and Firkins, I. 1997. Salinity adaptations of crayfish in Brittish Waters with particular<br />

reference to Austropotamobius pallipes, Astacus leptodactylus and Pasifastacus <strong>leniusculus</strong>. Estuarine, Coastal and<br />

Shelf Science 44: 147-154.<br />

Holdich, D. M., and Reeve, I. D. 1991. Alien crayfish in the British Isles. Report for the National Environment Research<br />

Council, Swindon.<br />

Holdich, D.M., Reynolds, J.D., C. Souty-Grosset, C. and Sibley, P.J. 2009. A review of the ever increasing threat to<br />

European crayfish from non-indigenous crayfish species. Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems 394-<br />

395, 11.<br />

Hurt, M. and Kivistik, M. 2009 Signaalvähi ja jõevähi levik ja arvukus Jägala jõestikus. Report for the Ministry of the<br />

Environment.<br />

Johnsen, S.I., Taugbøl, T., Andersen, O., Museth, J. and Vrålstad, T. 2007. The first record of the non-indigenous signal<br />

crayfish Pasifastacus <strong>leniusculus</strong> in Norway. Biological Invasions 9: 939-941.<br />

Johnsen, S.I. and Vrålstad T., 2009. Signal crayfish and crayfish plague in the Halden watercourse –<br />

proposition for a measurement plan, NINA Report 474, 29 p.<br />

Lewis, S.D. 2002. <strong>Pacifastacus</strong>, in Holdich D. M. (Ed.), Biology of freshwater crayfish. Blackwell Science, Oxford:<br />

511-540.<br />

Lowery R. S. and Holdich D. M. 1988. <strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong> in North America and Europe, with details of the<br />

distribution of introduced and native crayfish species in Europe, in Holdich D. M. and Lowery R. S. (Eds),<br />

Freshwater crayfish: biology, management and exploitation. Croom Helm, London: 283-308.<br />

Maguire I., Klobucar, G., Marcic, Z. and Zanella D., 2008. The first record of <strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong> in<br />

Croatia. Crayfish News: IAA Newsletter, 30, 4, 4.<br />

Nyström P. 1999. Ecological impact of introduced and native crayfish on freshwater communities: European<br />

perspectives, in Gherardi, F. and Holdich, D. M. (Eds), Crayfish in Europe as alien species. How to make the best of<br />

a bad situation. A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam: 63-85.<br />

Nyström P. 2002. Ecology, in: Holdich, D. M. (Ed.), Biology of freshwater crayfish. Blackwell Science, Oxford: 192-<br />

235.<br />

8

Peay, S. and Rogers, D. 1999. The peristaltic spread of signal crayfish (<strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong>) in the River Wharfe,<br />

Yorkshire, England. Freshwater Crayfish 12: 665-676.<br />

Petrusek A. and Petruskova T. 2007. Invasive American crayfish <strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong> (Decapoda:<br />

Astacidae) in the Morava River (Slovakia). Biologie, Bratislava, 62(3): 356–359.<br />

Pöckl M, Holdich DM and Pennerstorfer J (2006) Identifying native and alien crayfish species in Europe. Craynet, p 47.<br />

Sandodden, R. and Johnsen, S. I. 2010. Eradication of introduced signal crayfish Pasifastacus <strong>leniusculus</strong> using the<br />

pharmaceutical BETAMAX VET.®. Aquatic Invasions 5(1): 75-81.<br />

Skurdal J., Taugbøl T., Burba A., Edsman L., Söderbäck B., Styrishave B., Tuusti J. and Westman K. 1999. Crayfish<br />

introductions in the Nordic and Baltic countries, in Gherardi, F. and Holdich, D. M. (Eds), Crayfish in Europe as<br />

alien species. How to make the best of a bad situation. A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam: 193-219.<br />

Souty-Grosset C., Holdich D.M., Noël P.Y., Reynolds J.D. and Haffner P. (eds.) 2006. Atlas of Crayfish in Europe.<br />

Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, 187 p. (Patrimoines naturels, 64).<br />

Stebbing, P. D., Watson, G. J., Bentley, M. G., Fraser, D., Jennings, R. Rusthonm S. P. & Sibley, P. J. 2004. Evaluation<br />

of the capacity of pheromones for control of invasive non-native crayfish: part 1. English Nature Research Report<br />

No. 578. English Nature, Peterborough: 39 p.<br />

Stebbing, P. D., Watson, G. J., Bentley, M. G., Fraser, D., Jennings, R. & Sibley, P. J. 2005. Evaluation of the capacity<br />

of pheromones for control of invasive non-native crayfish: part 2. English Nature Research Report No. 633. English<br />

Nature, Peterborough, 46 p.<br />

Swahn, J.-Ö. 2004. The cultural history of crayfish. Bulletin Français de la Pêche et de la Pisciculture (372-373): 243-<br />

251.<br />

Söderhäll, I. and Söderhäll, K. 2002. Immune reactions,in: Holdich, D. M. (Ed.), Biology of freshwater crayfish.<br />

Blackwell Science, Oxford: 439-464.<br />

Söderhäll, K. 2004. Krasslig kräfta – tvivelaktig import. Miljöforskning 2004-08-10.<br />

Taugbøl T. and Skurdal J. 1999. The future of native crayfish in Europe: How to make the best of a bad situation?, in<br />

Gherardi F. and Holdich D. M. (Eds), Crayfish in Europe as alien species. How to make the best of a bad situation.<br />

A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam: 271-279.<br />

Troschel, H.J. and Dehus, P. 1993. Distribution of crayfish species in the Federal Republic of Germany, with special<br />

reference to Austropotamobius pallipes. Freshwater Crayfish 9: 390-398.<br />

Unestam, T. 1972. On the host range and origin of of the crayfish plague fungus. Rep. Inst. Freshw. Res.<br />

Drottningholm, 52: 192-198.<br />

Westman K. 1995. Introduction of alien crayfish in the development of crayfish fisheries: experiences with signal<br />

crayfish (<strong>Pacifastacus</strong> <strong>leniusculus</strong> (Dana) in Finland and the impact on the noble crayfish (Astacus astacus (L.)).<br />

Freshwater Crayfish 10: 1-17.<br />

Westman, K. and Nylund, V. 1979. Crayfish plague, Aphanomyces astaci, observed in the European crayfish, Astacus<br />

astacus, in Pihlajavesi waterway in Finland. A case study on the spread of the plague fungus. Freshwater Crayfish 4:<br />

419-426.<br />

Date of creation/modification of this species fact sheet: 08-11-2010<br />

9