Cactus Explorers Journal - The Cactus Explorers Club

Cactus Explorers Journal - The Cactus Explorers Club

Cactus Explorers Journal - The Cactus Explorers Club

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

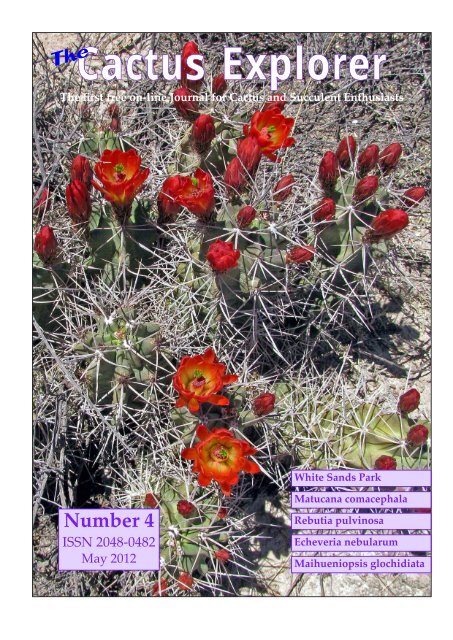

<strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

<strong>The</strong> first free on-line <strong>Journal</strong> for <strong>Cactus</strong> and Succulent Enthusiasts<br />

<strong>The</strong><br />

Number 4<br />

ISSN 2048-0482<br />

May 2012<br />

White Sands Park<br />

Matucana comacephala<br />

Rebutia pulvinosa<br />

Echeveria nebularum<br />

Maihueniopsis glochidiata

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

Regular Features<br />

Introduction 3<br />

News and Events 4<br />

Recent New Descriptions 8<br />

In the Glasshouse 16<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> Roundup 20<br />

<strong>The</strong> Love of Books 22<br />

Society Pages 70<br />

Plants and Seeds for Sale 74<br />

Books for Sale 76<br />

<strong>The</strong> two photos in the Echeveria laui article<br />

credited to J. Peck (<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer 2<br />

p. 37) should have been credited to M. Lesan.<br />

Cover Picture Echinocereus triglochidiatus at White Sands National Monument.<br />

Photo by Daiv Freeman. See his article on page 40.<br />

Invitation to Contributors<br />

In thIs EdItIon<br />

Please consider the <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer as the place to publish your articles. We welcome contributions<br />

for any of the regular features or a longer article with pictures on any aspect of cacti and<br />

succulents. <strong>The</strong> editorial team is happy to help you with preparing your work. Please send your<br />

submissions as plain text in a ‘Word’ document together with jpeg or tiff images with the<br />

maximum resolution available.<br />

A major advantage of this on-line format is the possibility of publishing contributions quickly<br />

and any issue is never full! We aim to publish your article within 3 months and the copy deadline<br />

is just a few days before the publication date which is planned for the 10th of February, May,<br />

August and November. Please note that advertising and links are free and provided for the<br />

benefit of readers. Adverts are placed at the discretion of the editorial team, based on their<br />

relevance to the readership.<br />

Publisher: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, Briars Bank, Fosters Bridge, Ketton, Stamford, PE9 3BF U.K.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer is available as a PDF file downloadable from www.cactusexplorers.org.uk<br />

<strong>The</strong> Editorial Team:<br />

Organiser:Graham Charles graham.charles@btinternet.com<br />

Scientific Adviser: Roy Mottram roy@whitestn.demon.co.uk<br />

Paul Hoxey paul@hoxey.com<br />

Zlatko Janeba desert-flora@seznam.cz<br />

Martin Lowry m.lowry@hull.ac.uk<br />

Opinions expressed in the articles are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the editorial team.<br />

Issues of the <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer may be freely distributed whilst the copyright of the text and pictures remains<br />

with the authors. Permission is required for any use of this material other than reading, printing or storage.<br />

2<br />

Articles<br />

Some notes on Wigginsia corynodes 26<br />

Gymnocalycium bayrianum 35<br />

A Visit to Cajas Bajo, Bolivia 37<br />

<strong>The</strong> Largest Echinocereus in the World(?) 40<br />

Does Mammillaria yucatanensis still exist? 46<br />

Matucana myriacantha and M. comacephala 50<br />

A Visit to Isla Esteban 58<br />

Travel with the <strong>Cactus</strong> Expert (3) 62<br />

Echeveria nebularum at a heady height 66<br />

<strong>The</strong> No.1 source for on-line information about cacti and succulents is http://www.cactus-mall.com<br />

This issue published on<br />

May 10th 2012

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

Back to the Glasshouse!<br />

May is one of the best months for flowers in<br />

the glasshouse here in England. Thankfully,<br />

this last winter was much kinder than the<br />

previous one so heating bills were much lower.<br />

I always look forward to March when the<br />

sunshine starts to feel warm on my face and<br />

the daytime temperature in the glasshouse<br />

regularly rises above 20°C. We had an<br />

unusually warm and sunny March this year,<br />

followed by the wettest April on record!<br />

It is a matter of judgement as to when to start<br />

watering your cacti. I usually begin with heavy<br />

sprays and start watering the pots when the<br />

plants are showing signs of expansion or<br />

growth. I do this when we have the first period<br />

of bright weather at the end of March but some<br />

years it can be mid-April. It is important not to<br />

leave the soft-bodied South American genera<br />

(Rebutia, Gymnocalycium, Parodia etc) dry for<br />

too long, since they can struggle to become<br />

completely turgid as the temperature climbs. I<br />

leave watering Mexican cacti a little longer and<br />

some, such as Ariocarpus and other sensitive<br />

genera, until May.<br />

Again, I am very grateful to the authors who<br />

have taken the trouble to write articles for the<br />

<strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer. We have a good selection,<br />

although I would have liked to publish more<br />

about the other succulents. It appears that<br />

more people are visiting habitats, and many of<br />

these travels are in search of succulents, so I<br />

hope to have more reports of these in future.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer team is pleased that<br />

relationships are now being established with<br />

other societies around the world. We are, for<br />

instance, exchanging advertisements so that<br />

our readers can see other organisations which<br />

may have a publication of interest.<br />

We want to make the information in the<br />

<strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer available to as many<br />

readers as possible. If you are responsible for<br />

the production of a journal and would like to<br />

reproduce one of our articles, then please ask.<br />

IntroduCtIon<br />

3<br />

As long as the author and photographers<br />

agree, then there should be no problem in<br />

granting permission. <strong>The</strong> reproduction in<br />

another language is especially welcome.<br />

If you go to the download page you can now<br />

download an index to the <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer. <strong>The</strong><br />

index is the cumulative index of all four<br />

editions published to date. I am very grateful<br />

to Roy Mottram for compiling this useful<br />

index.<br />

Now that the growing season has arrived<br />

here, I suspect that I shall receive less articles<br />

for the next issue. Please don’t be disappointed<br />

if the August issue is smaller. Unlike printed<br />

journals, we do not keep articles ‘in stock’ so<br />

the size of individual issues will vary.<br />

Of course, over the coming months, you may<br />

well see flowers on unusual cultivated plants.<br />

Please send us your digital pictures, with or<br />

without text, for use in our ‘In the Glasshouse’<br />

feature, although it could be in your garden if<br />

you are lucky enough to have a suitable<br />

climate!<br />

<strong>The</strong> editorial team thanks you for your<br />

continued interest and hope that those of you<br />

living in the northern hemisphere have a good<br />

growing season.<br />

GrahamCharles<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Meeting<br />

September 14-16th 2012<br />

Beaumont Hall, University of Leicester, UK<br />

See Page 7 for how to attend.<br />

<strong>The</strong> next issue of the <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer is<br />

planned for August 2012. If you have not already<br />

told me and would like to be advised<br />

when it is available for download, please<br />

send me your E-mail address to be added to<br />

the distribution list.<br />

Thank you for your interest and support!

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

nEws and EvEnts<br />

Mammillaria Society Members Day<br />

<strong>The</strong> Mammillaria Society Members Day and<br />

AGM, including two short talks and plant<br />

displays, will be held this year at Wisley RHS<br />

Gardens on Saturday 26th May 2012 and<br />

includes free garden entry for members.<br />

<strong>The</strong> day starts at 10am and more details can<br />

be obtained from the Chairman Chris Davies<br />

Gymno-Meeting in Carmagnola, Italy<br />

<strong>The</strong> 6th Gymno-Meeting will be held from<br />

Friday 27th- Sunday 29th July 2012.<br />

This year it is planned to further discuss the<br />

species of the G. hossei, G. catamarcense, and<br />

G. pugionacanthum complex.<br />

Venue: Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, Via<br />

San Francesco di Sales, 188, Carmagnola,<br />

ITALY.<br />

Details from Massimo Meregalli<br />

4<br />

Schütziana Vol. 3 Issue 1<br />

is available to download<br />

<strong>The</strong> latest issue of this free online journal for<br />

Gymnocalycium enthusiasts was published on<br />

March 16th. It contains an article about G.<br />

catamarcense by Jaroslav Procházka and the<br />

description of a new species G. meregallii,<br />

described by Ludwig Bercht and named for<br />

Massimo Meregalli, the famous Italian student<br />

of the genus.<br />

You can download this and the previous<br />

issues from:<br />

http://www.schuetziana.org/downloads.php<br />

GC<br />

It is with sadness that we report the recent<br />

death of Charles Craib, author of books<br />

about succulent plants, most recently ‘<strong>The</strong><br />

Bushman Candles’ co-written with John<br />

Lavranos.

Photo: G. Charles<br />

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

Derek Bowdery celebrates 80 years<br />

5<br />

Family and friends met at Derek’s home on<br />

May 8th to share his 80th Birthday with him.<br />

As well as measuring him against his Saguaro,<br />

we enjoyed pictures of his habitat adventures<br />

since the early 1980’s (when he had thick black<br />

hair!). He is known for his love of Ferocactus,<br />

about which he co-wrote the BCSS book with<br />

John Pilbeam, published in 2005. He also likes<br />

columnar cacti which enjoy growing in his<br />

huge glasshouse. GC<br />

<strong>The</strong>locactus Website Redesigned<br />

My favourite website about <strong>The</strong>locactus has<br />

been updated and redesigned. Alessandro<br />

Mosco has done a really good job and I am<br />

sure you will find his new site interesting and<br />

useful for identifying your plants. Look at<br />

http://www.thelocactus.cactus-mall.com GC<br />

Photo: G. Charles

Caricature drawn by Neil Slater<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

Another New online <strong>Journal</strong><br />

A new free online journal has just appeared.<br />

This is the first one published in French and it<br />

is called Succulentopi@<br />

<strong>The</strong> quality is excellent as you would expect<br />

from Yann Cochard and his very active team. It<br />

is available as a free download from:<br />

http://www.cactuspro.com/succulentopia<br />

Publisher: <strong>Cactus</strong>pro, association, 63360<br />

Saint-Beauzire, France, yann@cactuspro.com<br />

Publication Director: Yann Cochard<br />

Editor: Martine Deshogues<br />

Drafting Committee: Yann Cochard, Martine<br />

Deshogues, Alain Laroze, Philippe Corman,<br />

Maxime Leveque, and Eric Mare<br />

ISSN 2259-1060<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> is not printed, only distributed as<br />

a PDF file.<br />

Succulentopi@ is a magazine in PDF format<br />

published by ‘Le <strong>Cactus</strong> Francophone’ and its<br />

team. <strong>The</strong>ir goal is to publish it every three<br />

months, and to include articles, information,<br />

photos, etc. on the theme of cacti and other<br />

succulents.<br />

If you go to the website you can subscribe<br />

and receive notification as each issue is<br />

available.<br />

GC<br />

After his 90th Birthday event, Gordon<br />

Rowley invited people to visit him at his<br />

famous home ‘<strong>Cactus</strong>ville’. <strong>The</strong> moment of<br />

sharing part of his extensive library with Prof.<br />

Len Newton, President of the IOS, and BCSS<br />

achivist John Cox is caught by Neil Slater in<br />

this caricature.<br />

6<br />

Annual meeting of the<br />

Tephrocactus Study Group.<br />

Sunday 13th May 2011<br />

Venue : Great Barr ex Service Men and<br />

Women's club, Birmingham, UK, accessed via<br />

the drive between houses 280 & 278<br />

Perrywood Road, Great Barr. B42 2BJ Tel :<br />

0121 357 3870<br />

Illustrated talks by Graham Charles and Tony<br />

Roberts.<br />

Entrance is FREE to members AND visitors.<br />

A warm welcome awaits you!<br />

Lunch will be available for £5, but must be<br />

pre-booked. For more information and to book<br />

your lunch, please contact Alan Hill by Email<br />

or telephone 01142 462311.<br />

BCSS Oxford Branch<br />

with the Mammillaria Society<br />

OXFORD BRANCH SHOW<br />

Sunday 15th July 2012 at 10.30 am<br />

at Langdale Hall, Witney OX28 6AB U.K.<br />

(Cacti and Other Succulents)<br />

Lecture by Wolfgang Plein from the German<br />

Mammillaria Society (AfM) at 4:30 pm<br />

Information: Bill Darbon +44 (0)1993 881926

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> Weekend 2012<br />

Readers are invited to attend this year’s<br />

<strong>Cactus</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> Weekend. I expect there will<br />

be spaces available to enable new participants<br />

to attend. It will be held at Beaumont Hall at<br />

our usual Leicester University venue during<br />

the weekend of 14th to 16th September [the<br />

weekend after ELK]. Beaumont is where we<br />

met in 2011, and provides all the facilities close<br />

together. <strong>The</strong> day’s events and the meals will<br />

be in Beaumont Hall and the sleeping<br />

accommodation is nearby.<br />

I have booked Davide Donati from Italy and<br />

Ralf Hillman from Switzerland. Each will give<br />

us two talks. Davide Donati will speak about<br />

Somewhere in Mexico.<strong>The</strong> crazy adventures of a<br />

botanist and a talk about Corynopuntia. Ralf will<br />

speak about Patagonia in Springtime, and A<br />

Journey to South-eastern Bolivia.<br />

<strong>The</strong> price for the whole weekend, including<br />

accommodation in en-suite rooms, all meals<br />

and wine with dinner, is £190. Everything you<br />

pay goes to the direct costs of staging the<br />

event. <strong>The</strong>re is a private bar and time to<br />

socialise with like-minded people.<br />

You are welcome to bring plants, books or<br />

seeds to sell. <strong>The</strong>re is no charge and plants<br />

from known origin are particularly<br />

appreciated.<br />

Please Email me if you are interested in<br />

attending. GC<br />

ELK Meeting 2012<br />

<strong>The</strong> 47th staging of this ever-popular<br />

international meeting of cactus and succulent<br />

enthusiasts will take place from 7th to 9th<br />

September 2012 at the usual venue on the coast<br />

of Belgium, a short distance east of<br />

Blankenberge.<br />

7<br />

As well as the biggest plant sale in Europe,<br />

there will be five talks given in various<br />

languages:<br />

Friday 7th<br />

20.00h Cacti of Peru. Land of the Incas.<br />

Guillermo Rivera, Argentina<br />

Saturday 8th<br />

10.30h Echinocereus. Mieke Geuens, Belgium<br />

15.30h Kleine Chilenen: Bodenschätze unter<br />

den chilenischen Kakteen. Ricardo Keim,<br />

Chile.<br />

20.00h Cacti of the Marañon Valley, Peru.<br />

Graham Charles, U.K.<br />

Sunday 9th<br />

09.00 Echeveria. Jean-Michel Moullet, France.<br />

Details of the event can be found at<br />

www.elkcactus.eu

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

rECEnt nEw dEsCrIptIons<br />

Graham Charles tells us more about Maihueniopsis glochidiata from Argentina<br />

which he described as a new species in Cactaceae Systematics Initiatives 25 (2011)<br />

Fig.1 <strong>The</strong> type locality of Maihueniopsis glochidiata. A gentle slope near to a deep gorge at 2755m.<br />

In the <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer 3, I told the story<br />

of Cumulopuntia iturbicola and how the IOS<br />

molecular study had shown it to be a different<br />

species from those that were already<br />

described. <strong>The</strong> same study showed that a plant<br />

my friends and I had discovered in the Sierra<br />

Famatina, La Rioja, Argentina in 2000 was also<br />

new, an undescribed species of Maihueniopsis.<br />

December 1st 2000 started early for us. <strong>The</strong><br />

sun was still below the horizon as we prepared<br />

for the day’s adventure. We had spent the<br />

night in the pleasant town of Chilecito, where<br />

a local man, Sebastian, had created a cactus<br />

garden. He offered to take us in his pick-up<br />

high into the mountains on a mine road to see<br />

cacti. For me, the main objective was Lobivia<br />

famatimensis which I had not seen during any<br />

of my previous visits to the country.<br />

We drove along Rte.40 which skirts the<br />

8<br />

mountains to the east. Somewhere near the<br />

town of Famatina, we took a dirt road towards<br />

the mountains. <strong>The</strong> traffic appeared to be<br />

controlled at a gate where Sebastian spoke to a<br />

man who then let us through. Eventually, the<br />

road started climbing steeply and at our third<br />

stop the altitude was 2500m. We were in a<br />

Fig.2 Early morning in Chilecito, the Sierra Famatina<br />

beckons us for adventure.

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

Fig.3 <strong>The</strong> valley where we found Lobivia famatimensis at 2500m. <strong>The</strong> steep slopes were very loose and the plants<br />

were only in places where rocks or the roots of the bushes made the soil stable.<br />

Fig.4 Lobivia famatimensis GC407.03<br />

Fig.5 Pyrrhocactus andreaeanus GC407.06<br />

9<br />

steep-sided valley and exploration of one of<br />

the slopes revealed some pretty plants of<br />

Lobivia famatimensis (Figs.3 &4). This place was<br />

also a locality for Pyrrhocactus andreaeanus<br />

(Fig.5), the most northerly known form of P.<br />

strausianus which can have pink flowers<br />

although they often have yellow centres.<br />

<strong>The</strong> slopes proved to be home to eight cactus<br />

species including Denmoza rhodacantha and<br />

large plants of Echinopsis (Lobivia) formosa. <strong>The</strong><br />

other really interesting plant was another<br />

Lobivia which, at the time, I did not know<br />

occurred in the Sierra Famatina. <strong>The</strong> plant<br />

reminded us of Echinopsis (Lobivia,<br />

Acanthocalycium) thionantha. It has a bluish<br />

body and buds with dark hair (Fig. 6).<br />

This location would extend the previously<br />

known distribution of Echinopsis thionantha<br />

further south and into a different mountain<br />

range. I was able to collect some seeds from<br />

which the resulting seedlings and their<br />

flowers were very similar to those of E.<br />

thionantha and, like with that species, variable<br />

in colour from yellow to orange (Fig.7).

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

Fig.6 Four young plants of Lobivia kuehhasii GC409.01<br />

It was nine years later in 2009 that Walter<br />

Rausch published two new Lobivia names in<br />

the German journal KuaS, one of them, Lobivia<br />

kuehhasii is clearly the plant we saw in the<br />

Sierra Famatina and from near where we saw<br />

it.<br />

<strong>The</strong> type collection WR817b was made in<br />

1990 and in the WR field number list I have<br />

from 2008, it has the name Acanthocalycium<br />

thionanthum var. australis. I am not convinced<br />

that it is a separate species and I feel that a<br />

subspecies of E. thionantha would be more<br />

appropriate, bearing in mind its geographic<br />

disjunction.<br />

You may be wondering when I will tell you<br />

about the Maihueniopsis! Well, it was our next<br />

stop at 2755m. <strong>The</strong>re was some gently-sloping<br />

land (Fig.1) with a track leading down the<br />

slope from the road to a small building. We<br />

parked by the building where we could look<br />

down into a dramatic gorge with a river at the<br />

bottom (Fig.8). <strong>The</strong> water was an ochre colour<br />

which looked as if it originated from the soft<br />

rocks of the ravine.<br />

We looked around and I was interested to see<br />

a plant that looked like a small Echinopsis<br />

(Lobivia) formosa but already flowering when<br />

less than 15cm in diameter (Fig. 9). Nearby we<br />

had seen the normal form of the plant,<br />

growing to a large size and becoming short<br />

columnar. I concluded that this miniature form<br />

was the plant described by Rausch (1979) as<br />

Lobivia rosarioana, a name he later made a<br />

variety of Lobivia formosa. He tells us that the<br />

plant is rarely found in the Sierra Famatina.<br />

10<br />

Fig.7 Seedling of Lobivia kuehhasii GC409.01. 8cm pot.<br />

Fig.8 <strong>The</strong> ravine with the ochre-coloured river.<br />

Fig.9 Lobivia formosa rosarioana A small-growing form<br />

which flowers when only about 10cm in diameter.

Photo: Cyrill Hunkeler<br />

Photo: Cyrill Hunkeler Photo: Cyrill Hunkeler<br />

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

Fig.10 Maihueniopsis glochidiata<br />

HUN47 Cachipampa, Prov. Salta, Argentina 3120m<br />

Fig.11 Maihueniopsis glochidiata<br />

HUN47 Cachipampa, Prov. Salta, Argentina 3120m<br />

Fig.12 Maihueniopsis glochidiata<br />

HUN47 Cachipampa, Prov. Salta, Argentina 3120m<br />

My attention was drawn to a small Opuntia<br />

almost flat to the ground and with small<br />

coppery-yellow flowers (Fig.13). I thought it<br />

looked like a small-jointed relative of<br />

Maihueniopsis glomerata which is what I called<br />

it in my field list. <strong>The</strong> numerous glochids on<br />

11<br />

Fig.13 Maihueniopsis glochidiata GC407A at its type<br />

locality, 2755m in the Sierra Famatina, La Rioja.<br />

Fig.14 Maihueniopsis glochidiata GC407A in cultivation<br />

the old segments were very prominent in<br />

habitat. I brought home a few joints which<br />

grew well and now flower regularly (Fig.14).<br />

For years I watched the plant develop very<br />

prominent tufts of glochids on its older joints.<br />

<strong>The</strong> joint size had made me think the plant<br />

might be a form of Maihueniopsis minuta, so I<br />

called it M. aff. minuta in my Bradleya article<br />

about Maihueniopsis in 2008.<br />

When a survey of South American Opuntias<br />

was commissioned by the IOS, I donated a<br />

number of plant samples from my collection of<br />

documented plants, all with exact locality data.<br />

Among them was a segment of this plant. Dr<br />

Ritz, then at the University of Giessen, and her<br />

assistants extracted the DNA from the samples<br />

and undertook the study.<br />

<strong>The</strong> results (yet to be published in full)<br />

showed that GC407A was an undescribed<br />

species, distinct from M. minuta and all other

Photo: Cyrill Hunkeler<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

Fig.15 Maihueniopsis glochidiata HUN47 in cultivation<br />

described taxa. In preparation for the formal<br />

submission of the paper to an academic<br />

journal, the taxonomic implications were<br />

published in Cactaceae Systematics Initiatives<br />

25 (October 2011). As part of this process I<br />

published Maihueniopsis glochidiata as a new<br />

species.<br />

It is now clear that the type locality is not the<br />

only known habitat for this plant. In <strong>Cactus</strong><br />

Adventures 78 (2008), Joël Lodé published a<br />

picture of a Maihueniopsis from the Park of<br />

the Cardones, Province Salta, Argentina which<br />

he thought was M. minuta but which I now<br />

think is M. glochidiata.<br />

A location nearby has been confirmed by<br />

Cyrill Hunkeler (pers. com.) who also found a<br />

Maihueniopsis, HUN47, with small joints at<br />

3120m on the Cachipampa (Figs. 10-12). He<br />

also found the plant (HUN467) in the same<br />

mountain range as the type locality but further<br />

south on the Cuesta Miranda (Fig.16). This<br />

pass is where the well-travelled main road<br />

crosses the Sierra Famatina, but this is the first<br />

record I have seen for a Maihueniopsis being<br />

found there.<br />

Long before I found the species in habitat, I<br />

had been cultivating a plant of M. glochidiata,<br />

identified as M. minuta and said to have been<br />

collected by Herman Vertongen in 1992 on the<br />

Cachipampa. Presumably this is the same as<br />

HUN467, it certainly looks very similar to the<br />

plant in Fig.17.<br />

GC<br />

12<br />

Fig.16 Maihueniopsis glochidiata<br />

HUN467 Cuesta Miranda, La Rioja, Argentina 2425m<br />

Fig.17 Maihueniopsis glochidiata HUN467 in cultivation<br />

References<br />

Charles, G. (2008) Notes on Maihueniopsis<br />

Spegazzini. Bradleya 26:63-74<br />

Charles, G. (2011) Maihueniopsis glochidiata<br />

species nova. Cactaceae Systematics Initiatives<br />

25:20<br />

Lodé, J. (2008) Illustration of M. minuta.<br />

<strong>Cactus</strong> Adventures 78:13<br />

Rausch, W. (1979) Lobivia rosarioana Rausch<br />

spec. nov. KuaS 30(12): 284<br />

Rausch, W. (2009) Zwei neue Lobivien. KuaS<br />

60(12): 319-321<br />

Acknowledgement<br />

I should like to thank Cyrill Hunkeler for his<br />

help and permission to use his pictures. His<br />

website is very interesting for anyone who<br />

likes Opuntias (German language):<br />

http://www.tephroweb.ch<br />

Photo: Cyrill Hunkeler<br />

Photo: Cyrill Hunkeler

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

<strong>The</strong> discovery of Escobaria abdita Řepka & Vaško<br />

Finding a new species in habitat is a thrilling experience. Zdeněk Vaško tells us about how he<br />

discovered a recently-described tiny species of Escobaria in a flat basin which is seasonally<br />

flooded.<br />

Text and photos: Zdeněk Vaško; translation: Zlatko Janeba<br />

Fig.1. General view of the habitat of Escobaria abdita.<br />

In October 2010, I took off with two of my<br />

colleagues, Ladislav Vacek and Palo Jesenský,<br />

for a wedding ceremony of our good Mexican<br />

Fig.2. Fully hydrated Escobaria abdita with a flower bud.<br />

13<br />

friend. We decided to spend some time in the<br />

field before this happy event, and especially in<br />

areas we had never visited before. For some<br />

Fig.3. A view of the root system of Escobaria abdita.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

Fig.4. Another view of the habitat of Escobaria abdita.<br />

five years I have had the desire to discover<br />

Ariocarpus kotschoubeyanus somewhere north of<br />

Ocampo in the state of Coahuila. I used to<br />

have strange feelings and expectations while<br />

roaming various flood-plains in search of<br />

Ariocarpus, but I seemed to be out of luck.<br />

On October 16th 2010, we were exploring one<br />

14<br />

such flood-plain in northern Mexico, again<br />

without having any success. While slowly<br />

coming back to our vehicle where my friends<br />

were already waiting, having decided to leave<br />

the place, I kept searching the last few metres<br />

of the arid land. Some 30 metres from the car I<br />

noticed a tiny hole in the soil, resembling the<br />

Fig. 5 <strong>The</strong> flower of Escobaria abdita. Fig.6 A dry fruit of Escobaria abdita.

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

Fig.7 Escobaria abdita is completely sunken in the soil<br />

and difficult to find during the dry season.<br />

footprint of some small animal.<br />

I bent over and blew the dust layer away. For<br />

a moment I was left speechless , but then I<br />

immediately called to my friends. It was a<br />

wonderful sight and at the same time, an<br />

electrifying feeling. Although it was not my<br />

desired A. kotschoubeyanus, my excitement<br />

from discovering an apparently new Escobaria<br />

was so great. During a very short time of<br />

crawling on our hands and knees we were able<br />

to encounter about 50 more plants.<br />

In the field, the biggest of these Escobarias<br />

reach some 20mm in diameter and they<br />

evidently spend most of their life under the<br />

Fig.8 A grafted Escobaria abdita seedling in cultivation.<br />

15<br />

ground, in tiny holes. <strong>The</strong>ir beet-like root is<br />

succulent, solitary or very little branched,<br />

about 10cm long. <strong>The</strong> spines are round in<br />

cross-section, ivory in colour, and pectinately<br />

arranged on the areoles. Flowers are formed<br />

from the youngest areoles on the plant apex<br />

and are 35-45mm long and 30-35mm wide,<br />

whitish with pink to brown midstripes. <strong>The</strong><br />

style is green, with yellow anthers and the fruit<br />

is 6-8 mm long and 5-7mm in diameter, upon<br />

drying, becoming parchment-like.<br />

We named it Escobaria abdita. <strong>The</strong> name<br />

means hidden or concealed, because the plants<br />

are buried in the soil for most of the year and<br />

they are very difficult to find during the dry<br />

season.<br />

Reference<br />

Řepka, R. & Vaško, Z. (2011) Escobaria abdita<br />

- a new species from northern Mexico. CSJ(US)<br />

83(6): 264-269.<br />

Zdeněk Vaško,Czech Republic<br />

zdenek.vasko@atlas.cz<br />

More on Cumulopuntia iturbicola<br />

Following my article in the last issue of<br />

<strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer, Urs Eggli told me that the<br />

pictures I published reminded him of plants he<br />

had photographed in 1998 along the old RN 9,<br />

north of Humahuaca, about 8km south of Azul<br />

Pampa, Argentina. He saw all shades of flower<br />

colours from yellow to dark red (see picture<br />

above), and he thought at that time that he had<br />

found Cumulopuntia rossiana. In fact, I have yet<br />

to see an image of a genuine C. rossiana from<br />

Argentina .... any offers?<br />

GC<br />

Photo: U. Eggli

Photo: G. Charles<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

In thE GlasshousE<br />

Strophocactus chontalensis<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is something really special about<br />

growing and flowering an unusual plant. It<br />

was my work on the New <strong>Cactus</strong> Lexicon<br />

which opened my eyes to the many genera<br />

which are rarely seen in British collections. It<br />

made me realise what I had been missing, but<br />

it has not been easy to find suppliers of these<br />

rare plants.<br />

Strophocactus chontalensis first came to my<br />

attention when Ralf Bauer wrote his ‘Synopsis<br />

of the tribe Hylocereeae’ published in No.17 of<br />

Cactaceae Systematics Initiatives (2003). But<br />

the story began in 1940 when Tom MacDougall<br />

first collected the plant near San Miguel<br />

Tenango, Oaxaca, Mexico. <strong>The</strong> description of<br />

the new species was delayed until 1950 due to<br />

the lack of flowers to complete the description.<br />

MacDougall wrote an article about some<br />

epiphytic cacti of the region in the American<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> (XVIII):147-150 (1946). He described<br />

how he re-found the plant referred to with his<br />

16<br />

field number A44, the ‘Tenango Cereus’,<br />

growing only on rocks, often with Epiphyllum<br />

crenatum. <strong>The</strong> pictures in this article, and in the<br />

continuation on pages 165-168, show that the<br />

plant makes very large tangled groups of<br />

stems, each up to about a metre long tumbling<br />

over rocks. Flowers from this visit were then<br />

available to complete the description.<br />

<strong>The</strong> plant was eventually described as<br />

Nyctocereus chontalensis by Alexander in the<br />

Photo: G. Charles

Photo: G. Charles<br />

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

American <strong>Journal</strong> (XXII):131-3 (1950). <strong>The</strong><br />

genus was chosen because of the flowers and<br />

the specific name refers to the Chontal Indians<br />

who live in the area. Ralf Bauer in CSI 17<br />

(2003), believing that this species should be in<br />

the same genus as Deamia testudo and<br />

Strophocactus wittii, made the resulting new<br />

combinations under the oldest generic name,<br />

Strophocactus.<br />

My own encounter with Strophocactus<br />

chontalensis in habitat happened in 2006 when I<br />

was travelling in Oaxaca with Ivor Crook and<br />

David Yetman. It was my first visit to Mexico,<br />

an experience greatly enhanced by David’s<br />

experience of the country and his fluent<br />

Spanish.<br />

I had a vague memory of reading about the<br />

plant and its liking of growing on rocks in oak<br />

forest, but I did not think I would actually find<br />

it. We were driving along the main road from<br />

Mitla to Tehuantepec, passing through hills<br />

covered with oak woodland. It was February,<br />

the dry season, and there were no leaves on the<br />

trees.<br />

As we rounded one of the endless bends, I<br />

spotted a hillside which looked different, with<br />

prominent rounded exposed boulders under<br />

the trees. I shouted to David to stop the car. I<br />

think he wondered why I should want to stop<br />

there, since our main interest on the trip was to<br />

see the remarkable columnar cacti of the area.<br />

We crossed the road and walked a short<br />

distance up the hill, through deep piles of<br />

brown leaves, to the boulders. <strong>The</strong>re, growing<br />

on the tops of the rocks, were long cactus<br />

stems with few ribs, surely they must belong<br />

to S. chontalensis. <strong>The</strong>re were also two other<br />

17<br />

cacti, Mammillaria karwinskiana and what I took<br />

to be a species of Hylocereus. David, who has<br />

a passion for huge cerei, was unimpressed, but<br />

for me it was a highlight of the trip.<br />

I have now had the chance to cultivate this<br />

interesting plant and it has been a rewarding<br />

experience. It grows easily and quickly,<br />

forming a branched clump of stems close to<br />

the ground, making it suitable for a hanging<br />

pot. I am unsure about how much cold it can<br />

endure, but my plants have thrived with a<br />

winter minimum of 10°C. So far, my only<br />

disappointment is that only one of my two<br />

clones has produced flowers, so I have been<br />

unable to produce fruits and valuable seeds.<br />

However, I shall be able to propagate my<br />

plants by cuttings which root easily.<br />

GC<br />

Pfeiffera miyagawae<br />

As I have mentioned before, working on the<br />

New <strong>Cactus</strong> Lexicon opened my eyes to the<br />

diversity and interest of epiphytic genera like<br />

Pfeiffera. I had the impression that the flowers<br />

were usually small and white which many are,<br />

but there are exceptions. One of those<br />

exceptions is the remarkable Pfeiffera miyagawae<br />

(see picture on the next page).<br />

<strong>The</strong> plant illustrated is a clone distributed by<br />

the ISI under their number 91-18. It is the type<br />

clone, HBG 50888, collected on October 19th<br />

1974 by Mario Miyagawa at 600m in the<br />

yungas of Alto Beni, near Mataral, Dept.<br />

Cochabamba, Bolivia. Ralf Bauer, in Cactaceae<br />

Systematics Initiatives 20, reports that the<br />

plant has never been re-found at the stated<br />

locality but has subsequently been found by<br />

Photo: G. Charles

Photo: G. Charles<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

Wolfgang Krahn in Dept. La Paz, Prov. Sud<br />

Yungas, south of La Asunta at 750m. It is<br />

thought that the original locality was near this<br />

place and that the stated locality in Dept.<br />

Cochabamba was a misunderstanding.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first description was published in 1987<br />

by Wilhelm Barthlott and Werner Rauh in the<br />

American journal. Mario Miyagawi had been a<br />

student of theirs. As they say, the flowers are<br />

reminiscent of Corryocactus (Erdisia). After<br />

some consideration, they concluded that the<br />

plant was best placed in Pfeiffera. <strong>The</strong> recent<br />

molecular study of Pfeiffera and its relatives by<br />

Karotkova et al. confirms its placement in<br />

Pfeiffera and shows its close relationship to P.<br />

ianthothele, the type of the genus.<br />

It has proved to be very easy to cultivate and<br />

flowers freely towards the ends of the stems.<br />

Propagation is also straightforward, cuttings<br />

rooting easily. <strong>The</strong> stems are somewhat lax and<br />

so a hanging pot in a part shade position suits<br />

this lovely plant in cultivation.<br />

References<br />

Barthlott, W. & Rauh, W. (1987) Pfeiffera<br />

miyagawae. A new orange flowered species<br />

from Bolivia. CSJ(US) 59(2): 63-65<br />

Bauer, R. (2005) More notes on Pfeiffera.<br />

CSI(20): 6-10<br />

Karotkova, N. et al. (2010) A phylogenetic<br />

analysis of Pfeiffera... Willdenowia 40: 151-172<br />

GC<br />

18<br />

<strong>The</strong>locactus panarottoanus or flavus?<br />

This species and its habitat have been well<br />

known for a long time. It can be found in the<br />

field lists of Lau and Reppenhagen described<br />

as a yellow-flowering <strong>The</strong>locactus tulensis. <strong>The</strong><br />

first description as a new species was by Josef<br />

Halda (1998) as <strong>The</strong>locactus panarottoanus. <strong>The</strong><br />

type locality was stated to be near La Hincada,<br />

San Luis Potosi, Mexico at 1100m.<br />

Alessandro Mosco and Carlo Zanovello,<br />

presumably in ignorance of the Halda name,<br />

called the same taxon <strong>The</strong>locactus flavus in a<br />

well-illustrated article in <strong>Cactus</strong> & Co (1999).<br />

<strong>The</strong>y later decided that it was better treated as<br />

a subspecies of T. conothelos and made the<br />

combination in Bradleya (2000). So, there are<br />

two names for this plant. As a species, T.<br />

panarottoanus has priority, but as a subspecies<br />

the correct name is T. conothelos ssp. flavus.<br />

In cultivation, it is easily grown in a sunny<br />

locality and, for me, first flowered in a 10cm<br />

pot. <strong>The</strong> long spines and yellow flowers make<br />

it an attractive addition to a collection but, as<br />

yet, is not often seen in UK.<br />

References<br />

Halda, J (1998) <strong>The</strong>locactus panarottoanus<br />

spec.nov. Acta Musei Richnoviensis, Sect.<br />

Natur. 5(4):161<br />

Mosco, A. & Zanovello, C. (1999) <strong>The</strong>locactus<br />

flavus. <strong>Cactus</strong> & Co. 3(1): 20-23<br />

Mosco, A. & Zanovello, C. (2000) A phenetic<br />

analysis of the genus <strong>The</strong>locactus. Bradleya<br />

18:45-70<br />

GC<br />

Photo: G. Charles

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

Disocactus nelsonii<br />

For me, there is something particularly<br />

appealing about pink flowers. I became more<br />

interested in epiphytic cacti while working on<br />

the New <strong>Cactus</strong> Lexicon when we had the<br />

opportunity to see really good images of many<br />

unusual species photographed by Ralf Bauer.<br />

One I particularly noticed was this species and<br />

its beautiful flower so I asked Ralf for a cutting.<br />

<strong>The</strong> piece he gave me has grown well and<br />

now produces masses of flowers in March each<br />

year. <strong>The</strong> stems hang down so it is a good<br />

plant for a well-watered hanging pot placed in<br />

a lightly shaded part of the glasshouse.<br />

It was first described in 1913 as a species of<br />

Epiphyllum by Britton and Rose, but when<br />

they wrote their monumental work ‘<strong>The</strong><br />

Cactaceae’, they erected the monotypic genus<br />

Chiapasia for it in Volume 4 (1923). This<br />

generic name refers to the Mexican state of<br />

Chiapas where the plant was found.<br />

Britton and Rose had originally described the<br />

new species from a herbarium specimen<br />

collected by E.W.Nelson in 1896 but they also<br />

19<br />

refer to an illustration of a living plant<br />

cultivated by Purpus and published in MfK in<br />

1918 as Phyllocactus chiapensis.<br />

<strong>The</strong> natural habitats of this plant are found in<br />

Guatemala as well as Chiapas where it is said<br />

to grow epiphytically on oak trees, as was the<br />

type collection. An excellent comprehensive<br />

account of Disocactus nelsonii was written by<br />

Myron Kimnach and published in the<br />

American journal of 1958. He agrees with the<br />

placement of this species in Disocactus, first<br />

made by Lindinger in 1942 in a largely<br />

overlooked paper. GC<br />

References<br />

Britton, N.J. & Rose, J.N. (1923) Chiapasia<br />

gen. nov. <strong>The</strong> Cactaceae IV: 203<br />

Lindinger, K. (1942) Bot. Centralbl. Beih.<br />

61:383<br />

Kimnach, M. (1958) Icones Plantarum<br />

Succulentarum 13 Discocactus nelsonii. <strong>Cactus</strong><br />

and Succulent Society of America <strong>Journal</strong><br />

XXX(3):80-83<br />

Purpus, J.A. (1918) Phyllocactus (Epiphyllum)<br />

chiapensis spec. nov. Monatsschrift für<br />

Kakteenkunde 28:118-121<br />

Photo: G. Charles

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> roundup<br />

New Editors for <strong>Cactus</strong>World<br />

<strong>The</strong> British <strong>Cactus</strong> and Succulent Society<br />

publish their journal ‘<strong>Cactus</strong>World’ four times<br />

a year. It contains information about the<br />

Society’s activities and articles on a wide range<br />

of subjects. Following the retirement of Roy<br />

Mottram, the publication’s excellent editor for<br />

the past six years, the Society has appointed Al<br />

Laius as the new editor. He has the support of<br />

Peter Berresford, who has accepted the role of<br />

deputy editor. Al is known for his love of<br />

Sansevieria and Peter is a well-travelled<br />

Echinocereus specialist.<br />

<strong>The</strong> new editors promise to introduce new<br />

features and plan to modify the content in line<br />

with what the members have requested. So, in<br />

future there will be more about cultivation and<br />

selected taxa, but less long travelogues and<br />

technical articles which will be accommodated<br />

within Bradleya, the Society’s yearbook.<br />

<strong>The</strong> March 2012 issue of <strong>Cactus</strong>World, the<br />

first to be edited by the new team, features a<br />

long article from Johan de Vries attempting to<br />

clarify the application of three old Cárdenas<br />

species names for plants now regarded as<br />

Sulcorebutias.<br />

20<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are also articles about the Jardin<br />

Exotique in Monaco; the Indian distribution of<br />

a Caralluma; Opuntia fragilis hybrids; cacti on<br />

St Lucia; Mammillaria bombycina; the Luton<br />

Hoo garden project and a revision of the series<br />

Cepaea in the genus Sedum.<br />

<strong>The</strong> regular features ‘BCSS News’, ‘<strong>Cactus</strong><br />

Talk’ and ‘Literature review’ are joined by new<br />

ventures ‘Plant of the quarter’, ‘In my<br />

greenhouse’ and ‘Succulent snippets’. This<br />

issue is 8 pages longer than usual at 72 pages<br />

and continues to be excellent value for the<br />

modest subscription of £15 (UK) or £20 (worldwide)<br />

per year (Bradleya is available at an<br />

additional charge).<br />

You can contact the editors by email:<br />

Al Laius editor@bcss.org.uk<br />

Peter Berresford deputyeditor@bcss.org.uk<br />

Subsciption information and everything else<br />

you could want to know about the BCSS can be<br />

found at http://www.bcss.org.uk GC<br />

English edition now available<br />

<strong>The</strong> long-running Italian journal ‘Piante<br />

Grasse’ is now published in an English edition.<br />

<strong>The</strong> quality of the pictures, layout and content<br />

are all excellent so I hope you will consider<br />

supporting this brave venture by visiting their<br />

very informative website:<br />

http://www.piantegrassejournal.it/eng/index.html

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

Minimus: <strong>Journal</strong> of Czech Notocactophiles<br />

<strong>The</strong> last issue of the <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> included a short article about<br />

Internoto, the German language journal<br />

focusing on the genus Notocactus. <strong>The</strong>re is a<br />

similar journal in the Czech Republic. It has<br />

been published since 1970, so its history is ten<br />

years longer than that of Internoto.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Czech study group for Notocactus,<br />

called Notosekce in Czech, was established in<br />

early 1970 and its first general meeting was<br />

held in August 1970. Among those present at<br />

this meeting was also the famous Dutch<br />

cactophile A.F.H. Buining who had come to<br />

Czechoslovakia to deliver a lecture about his<br />

travels in Brazil.<br />

<strong>The</strong> number of members climbed to 123<br />

within a year. At the peak of the Notocactus<br />

craze in the late 1970s, fuelled by discoveries of<br />

many new species and forms of Notocactus in<br />

southern Brazil, Notosekce had more than 230<br />

members. Throughout the 1980s the number of<br />

members kept at just below 200 but it started<br />

to fall after 1990 when the attention of many<br />

Czech cactus lovers shifted to Mexico. In recent<br />

years, the number of members has fluctuated<br />

around 60, including several members from<br />

abroad (Germany). Annual general meetings<br />

are held every August.<br />

21<br />

‘Minimus’ was originally published monthly,<br />

then quarterly, and since the early 1990s two<br />

double issues per year are published. <strong>The</strong><br />

journal has a colour photo on the cover and<br />

black-and-white photos inside. Articles in the<br />

recent issues have included travelogues of<br />

Stanislav Stuchlik (chairman of Notosekce)<br />

and Norbert Gerloff from Germany about their<br />

respective travels in southern Brazil, as well as<br />

articles on cultivation and treatises on selected<br />

species. Short German-language summaries of<br />

all articles are published at the end of each<br />

issue.<br />

<strong>The</strong> name ´Minimus´ is after Notocactus<br />

minimus, a rather mystical Fric name, which<br />

was referred to Notocactus (Parodia)<br />

tenuicylindricus in the New <strong>Cactus</strong> Lexicon.<br />

However, according to botanists Zazvorka and<br />

Sedivy who published a review of Fric names<br />

in 1993, Notocactus minimus Fric et Kreuzinger<br />

(1935) was validated by Buining in Succulenta<br />

in 1940 and thus the name N. minimus has<br />

priority over N. tenuicylindricus Ritter (1970).<br />

Rene Samek<br />

Czech Republic<br />

renesamek@hotmail.com

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

thE lovE of Books<br />

News of Recent Publications. A Reminder of Old Favourites.<br />

Many cactophiles enjoy reading about their plants, particularly in the winter when our<br />

collections are less demanding. This feature aims to provide you with inspiration.<br />

101 <strong>Cactus</strong> del Perú<br />

Peru is surely one of the most important<br />

countries when considering the cactus flora of<br />

the world. It has a remarkable diversity of<br />

biogeographic zones ranging from the very<br />

dry coastal strip to tropical rain forest. Many of<br />

these zones support cacti. Some species are<br />

small and hard to find but others are dramatic<br />

trees.<br />

Dr. Carlos Ostolaza is very well known to<br />

enthusiasts around the world for his work<br />

with cacti in Peru over many years. He has<br />

been a pioneer in the education of the Peruvian<br />

people about the importance of their floral<br />

heritage and the need to conserve it. In 1987 he<br />

founded QUEPO, the Peruvian <strong>Cactus</strong> and<br />

Succulent Society and still edits their annual<br />

journal.<br />

This impressive book has been printed and<br />

published in Peru and, being written in<br />

Spanish, should further promote interest<br />

within the country. As in many countries, the<br />

cacti in Peru face pressures on their survival<br />

from infrastructure developments such as<br />

dams, roads and mines, as well as the<br />

expansion of agriculture. <strong>The</strong> long-term<br />

22<br />

conservation of cacti depends to a great extent<br />

on the value placed on them by the local<br />

people. It is to be hoped that books like this<br />

will help spread understanding of the plants<br />

and the need for their conservation.<br />

<strong>The</strong> volume is hardbound, 240 x 273mm<br />

landscape, 256 pages. <strong>The</strong>re are 546 colour<br />

photographs, all reproduced at a good size.<br />

<strong>The</strong> non-technical text is written in Spanish.<br />

<strong>The</strong> 101 species described are about 40% of<br />

the cacti found in Peru and have been well<br />

chosen to represent the diversity of the family.<br />

Many of the featured species are popular in<br />

cultivation and are usually illustrated in<br />

culture and also in habitat. A brief description<br />

is given for each taxon together with an<br />

indication of its known distribution.<br />

Some potential readers might be put off by<br />

the Spanish text but the pictures alone make it<br />

a valuable reference and the text is quite easy<br />

to follow even if you understand only a little of<br />

the language.<br />

You can watch the launch of the book on<br />

youtube.<br />

Carlos tells me that Mildred Margot Canales<br />

Azabache has copies of the book in Spain<br />

available for sale at 60€. You can contact her by<br />

email.<br />

GC<br />

Looking for a second hand book?<br />

You can search the stock of book dealers<br />

around the world by using one of the<br />

specialist web sites for example:<br />

http://www.addall.com/Used<br />

http://www.bookfinder.com<br />

http://www.abebooks.com

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

<strong>The</strong> Genus Gymnocalycium<br />

Another new book about this popular genus<br />

has just been published by the German <strong>Cactus</strong><br />

Society (DKG) as the seventh title of their<br />

series of handbooks for the collector. In the<br />

<strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer 2, we reported on the<br />

recently published Parodia book from the<br />

same series.<br />

This attractive volume has been written (in<br />

German) by Detlev Metzing, well known as a<br />

specialist in Gymnocalycium. <strong>The</strong> treatment is<br />

based on recent molecular studies and agrees<br />

quite closely with that which I followed in my<br />

‘Gymnocalycium in Habitat and Culture’.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re have been changes in the application of<br />

names and a number of new names published<br />

recently, so it is good to have a period of<br />

stability.<br />

144 pages, softbound, 240 x 170mm with 200<br />

colour pictures and 9 maps (German).<br />

Produced to the usual high standard we have<br />

come to expect from the DKG, the pictures are<br />

very well reproduced.<br />

As with the other titles in this series, it is<br />

available only to members of the DKG. <strong>The</strong><br />

price is 10 € (including p.&p.) for delivery to<br />

Germany and 12 € for the rest of the world.<br />

It can be purchased from the website of the<br />

DKG: www.dkg.eu.<br />

23<br />

<strong>Cactus</strong> File Handbook 6<br />

This, the last title in a useful series of books,<br />

was the most ambitious. John Pilbeam had<br />

already written one book about Mammillaria,<br />

probably the single most popular of all cactus<br />

genera. His first volume ‘Mammillaria - A<br />

Collector’s Guide’ was published in 1981 and<br />

proved a popular reference to enthusiasts. At<br />

that time, the use of colour for pictures was<br />

limited by cost, so most species had only a<br />

black and white photograph. To overcome this,<br />

John published a series of colour pictures<br />

referred to the relevant page in the book. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

were well produced and reproduced at a good<br />

size (17.5 x 13cm).<br />

<strong>The</strong> arrival of John’s <strong>Cactus</strong> File Handbook<br />

about Mammillaria in 1999 was greeted with<br />

universal acclaim. It combined his informative<br />

text with good colour pictures placed with the<br />

relevant text, so much better than putting all<br />

the pictures in a block within the book. It is an<br />

extremely useful reference and remains my<br />

personal favourite of John’s many books.<br />

New copies are still available, priced at £45<br />

from Keiths Plant Books or direct from John<br />

Pilbeam<br />

GC

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

BOOKS FOR SALE<br />

<strong>The</strong> Cactaceae. Descriptions and illustrations of<br />

plants of the cactus family, 4 vols.<br />

Part original, 1919-1923, & part reprint, 1937.<br />

Comprising Vols. 1, 2 & 4 of ed.2, large paper, with<br />

a large proportion of the ed.1 colour plates, plus<br />

Vol. 3 ed.1. 985 pages, 76 [of 107] chromolithographs,<br />

1120 text-figs; hardbound in standard black rexine<br />

library binding by Glass & Foster in 1975.<br />

PROVENANCE: <strong>The</strong> odd Vol.3 of the first edition<br />

in this set was rescued from the Abbey Garden<br />

Press disastrous fire of 1960, which destroyed the<br />

presses and most of the unsold book stocks and<br />

library. This set was put together to become the<br />

personal copy of Bob Foster (1938-2002) and it<br />

bears his bookplate dated 19 Jan 1970. It then<br />

entered the Abbey Garden Press Library, with its<br />

bookplate nr.388, dated 1975. On dispersal of the<br />

Abbey Garden Press library, it was bought by the<br />

Whitestone Gardens library in 1998, the present<br />

owner.<br />

CONDITION: A pleasing set comprising a Vol. 3<br />

from the 1st. ed. & Vols. 1,2, & 4 from the large<br />

paper 2nd. ed. in a very clean, hardly opened<br />

condition, apart from slight damage to Vol.3<br />

resulting from the Abbey Garden Press fire, but<br />

this is not obtrusive. Contains 76 original colour<br />

plates out of a possible 107: 19 in Vol.1, 20 in Vol. 2,<br />

19 in Vol. 3, and 18 in Vol. 4. Vol. 3 has a badly<br />

24<br />

soiled title page and slight tear in the lower<br />

margin. <strong>The</strong> first four leaves are water-stained<br />

along the lower margin. A few coloured and plain<br />

plates are loose, as though inserted later. <strong>The</strong><br />

frontispiece photo of Vol. 3 is a later printing.<br />

HISTORY: This seminal work first appeared<br />

softbound in printed wrappers, at intervals<br />

between 1919 and 1922. It was out of print by the<br />

mid-1930s so Scott Haselton, the founder of Abbey<br />

Garden Press, decided to issue a reprint. This<br />

appeared in 1937 in two formats, the larger run of<br />

500 copies being a large paper version similar in<br />

size to the original.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Carnegie Institution had random sets of a<br />

little over 40 of the colour plates from the first<br />

edition left over, and Haselton bound these into a<br />

few of his second editions until stocks were<br />

exhausted, which were otherwise published in<br />

monochrome throughout. Thus, copies with 21-41<br />

colour plates can be found. Volumes 1,2 & 4 of the<br />

present set are from this source, while Vol. 3 is<br />

from a first edition set in the Abbey Garden Press<br />

library that survived the 1960 fire, so is original<br />

and consequently has the full complement of 19<br />

colour plates.<br />

Scott Haselton lost interest after his marriage in<br />

1962 and the trauma of the fire so the business<br />

languished until 1967 when Charlie Glass and Bob<br />

Foster entered into partnership and bought the<br />

assets of the Abbey Garden Press along with its<br />

library. Charlie died in February 1998, and in<br />

March of that year Bob Foster instructed a<br />

Californian bookseller to dispose of the Abbey<br />

Garden library.<br />

PRICE: Offers invited in the region of £850 or<br />

higher, plus postage. UK postage £25 by Special<br />

Delivery; Europe £57; Rest of World £115. It will go<br />

to the person making the best offer by 1st June<br />

2012.<br />

Roy Mottram, Whitestone Gardens, Sutton,<br />

Thirsk, North Yorkshire YO7 2PZ, UK. Phone:<br />

01845597467 (UK), (+)441845597467 (internl.).<br />

Fax: 01845597035 (UK), (+)441845597035 (internl.).<br />

Email: roy@whitestn.demon.co.uk.<br />

A free digital version of the first edition of this<br />

work can be viewed or downloaded at:<br />

http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/100137#pa<br />

ge/213/mode/1up<br />

If you have a rare book for sale, you can<br />

advertise it free in the <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer.<br />

Please include interesting historical details.

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

Mesembs<br />

<strong>The</strong> Titanopsis Group<br />

Steven A Hammer<br />

New Series of Books<br />

by Steven Hammer<br />

Little Sphaeroid Press has joined forces with<br />

Steven Hammer to produce a series of eight<br />

new books that describe and illustrate every<br />

compact collectable member of the Living<br />

Stones from the unique perspective of this<br />

well-known and widely travelled mesemb<br />

expert.<br />

Everyone knows Steven Hammer's hundreds<br />

of articles, dozens of new species descriptions,<br />

32 trips to South Africa, and three major books<br />

on Conophytum and Lithops. Now this new<br />

series is out to capture the rest of his life's<br />

work, beginning with a book about 9 genera of<br />

the Titanopsis Group. Forty related species<br />

will be covered in detail—their histories, their<br />

habitats and their horticultural peculiarities for<br />

the first time in book form.<br />

For information about how to pre-order this<br />

first title and more about the series, visit<br />

http://www.littlesphaeroid.com<br />

25<br />

Stev en Hammer’ s<br />

VANHEERDEA<br />

DIDYMAOTUS<br />

IHLENFELDTIA<br />

NANANTHUS<br />

PREPODESMA<br />

A TI D ENFEL L H I<br />

DIDYMAOTUS ANHEERDEA<br />

V<br />

MESEMBS<br />

<strong>The</strong> T he Titanopsis Group Gr Group<br />

TANQUANA<br />

TITANOPSIS<br />

TIT<br />

ALOINOPSIS<br />

AL<br />

DEILANTHE<br />

ANQU T<br />

ALOINOPSIS DEILANTHE<br />

ANOPSIS<br />

TIT<br />

ANQUANA<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

new<br />

series from<br />

Ste Steven ven<br />

Hammer<br />

–<br />

one<br />

of<br />

the<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

www www.littlesphaer .littlesphaeroid.com<br />

LITTLE<br />

SPHAEROID PRESS,<br />

OAK<br />

L LAND,<br />

CALIFORNIA

Photo: A. Hofacker<br />

Photo: A. Hofacker<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

Some noteS on WigginSia corynodeS<br />

Andreas Hofacker explains the complicated history of some Wigginsia species<br />

names, makes a new combination and designates neotypes where appropriate.<br />

Fig.1 Echinocactus corynodes in cultivation.<br />

Fig.2 A plant discovered in Northern Uruguay, which resembles<br />

the first description of Echinocactus corynodes.<br />

In scientific literature (e.g. Hunt 2006,<br />

Anderson 2001), and increasing in literature<br />

from cactus enthusiasts, the genus Parodia<br />

Spegazzini is understood in a broader sense to<br />

include the genera Notocactus (K. Schumann)<br />

Frič, Acanthocephala Backeberg (= Brasilicactus<br />

26<br />

Fig.3 Echinocactus corynodes in Northern Uruguay.<br />

Backeberg nom. inval.), Eriocephala Backeberg (=<br />

Eriocactus Backeberg nom. inval.), Brasiliparodia<br />

F. Ritter and Wigginsia D.M. Porter.<br />

Albesiano & Kiesling (2009) published a paper<br />

where they rehabilitated the genus Wigginsia<br />

as separate from Parodia. <strong>The</strong>re, they deal with<br />

different plants of the genus Wigginsia.<br />

Unfortunately, this paper contains some errors,<br />

which need to be corrected.<br />

In April 1905, Karl Schumann described a<br />

plant that he named Echinocactus (Malacocarpus)<br />

arechavaletai, not knowing that in January of the<br />

same year, Carlos Spegazzini (1905) also<br />

described a plant with the name Echinocactus<br />

arechavaletai. <strong>The</strong> latter plant is today included<br />

in Parodia ottonis (Lehmann) N.P. Taylor, whilst<br />

Schumann’s plant is included in the genus<br />

Wigginsia. <strong>The</strong> descriptions were based on<br />

different plants and therefore the name<br />

Echinocactus arechavaletai Spegazzini has<br />

priority over Echinocactus arechavaletai K.<br />

Schumann, because Echinocactus arechavaletai<br />

K. Schumann is a younger homonym of<br />

Echinocactus arechavaletai Spegazzini and is<br />

therefore illegitimate (ICBN Art 53.1).<br />

In the same publication, Spegazzini also<br />

Photo: A. Hofacker

Number 4 May 2012 ISSN 2048-0482 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer<br />

Fig.4 <strong>The</strong> first description of Echinocactus corynodes<br />

from Pfeiffer.<br />

published the name Echinocactus acuatus var.<br />

arechavaletai (K. Schumann) Spegazzini. This<br />

plant is identical with Schumann’s Echinocactus<br />

arechavaletai and therefore Spegazzini<br />

published the first valid description of this<br />

taxon. Even if in the first description there is<br />

no provenance given, Spegazzini’s indication<br />

of Schumann as author of the name shows that<br />

it is the same plant. Schumann’s plant was<br />

collected by the Czech cactus-collector Alberto<br />

Vojtěch Frič in 1903 and originates from<br />

Piriápolis in southern Uruguay. Guillermo<br />

Herter (1930) created the new replacement<br />

name Echinocactus maldonadensis, the first<br />

correct name at specific level. Herter also<br />

published the combination of this taxon in<br />

Notocactus hence Notocactus maldonadensis<br />

(Herter) Herter (Herter 1943). Havliček (1989a:<br />

79) then created the new name Notocactus<br />

neoarechavaletai, referring to the same plant that<br />

was described as Echinocactus acuatus var.<br />

arechavaletai and renamed at specific level as<br />

Echinocactus maldonadensis. <strong>The</strong> whole history<br />

of the names is described in detail in Albesiano<br />

& Kiesling.<br />

In their publication, Albesiano & Kiesling<br />

deal with a plant that was described as<br />

Echinocactus corynodes Pfeiffer, today included<br />

in the genus Parodia. Wigginsia corynodes<br />

(Pfeiffer) D.M. Porter was first described by the<br />

German doctor and botanist Ludwig<br />

(Ludovico) Pfeiffer (1837a). In their paper,<br />

Albesiano & Kiesling try to prove that<br />

27<br />

Fig.5 Pfeiffer’s German translation from the first<br />

description of Echinocactus corynodes.<br />

Wigginsia corynodes is identical with plants that<br />

are known as Wigginsia arechavaletae or<br />

Notocactus neoarechavaletae and therefore the<br />

name Wigginsia corynodes must be used for<br />

these plants. A neotype of Echinocactus<br />

corynodes was designated as plate 24 on page<br />

243 in Arechavaleta (1905). In the protologue,<br />

the authors also synonymize Wigginsia horstii<br />

F. Ritter [= Notocactus neohorstii <strong>The</strong>unissen =<br />

Parodia neohorstii (<strong>The</strong>unissen) N.P. Taylor]<br />

with Wigginsia corynodes.<br />

Fig.6 <strong>The</strong> first published picture and neotype of<br />

Echinocactus corynodes in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine.<br />

Vol. 68 [ser. 2, vol. 15]: t. 3906.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Cactus</strong> Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 4 May 2012<br />

Stem shape<br />

Stem colour<br />

Pfeiffer,Echinocactus<br />

corynodes in„Enumeratio<br />

…”<br />

Subglobose, attenuate<br />

in direction to base<br />

Dark green Young<br />

plants brighter green<br />

Pfeiffer,Echinocactus<br />

corynodes<br />

in„Beschreibung …“<br />

Subglobose<br />

Dark green Young<br />

plants bright green<br />

28<br />

Albesiano & Kiesling<br />

for Echinocactus<br />

corynodes<br />

Subglobose, attenuate<br />

in direction to base<br />

Shape of apex Submerged Submerged Submerged<br />

Spegazzini<br />

Echinocactus acuatus<br />

var. arechavaletai<br />

Albesiano & Kiesling<br />

for Echinocactus acutus<br />

var. arechavaletai<br />

Subglobose Subglobose<br />

Dark green Dark green, bright Dark green, bright<br />

Moderately<br />

submerged<br />

Moderately<br />

umbilicated<br />

Stem diameter Not indicated Not indicated 7.5–10cm 30–100mm 3–10cm<br />

Stem height Not indicated Not indicated 5-7.5cm 30–100mm 3–10cm<br />

Number of ribs 16 16 16 13-21 13–21<br />

Rib shape<br />

Areoles<br />

Areole separation<br />

Radial spine number<br />

Radial spine colour<br />

Narrow, acute, edges<br />

crenate<br />

Impressed. Younger<br />

ones woolly, white,<br />

later deciduous<br />

6-8 Linien Kurhessen:<br />

1.2cm–1.6cm Prussia:<br />

?<br />

10 in young plants,<br />

9 in adult plants<br />

first red, then brownish,<br />

young plants<br />

white<br />

Narrow, acute, edges<br />

crenate<br />

With white wool,<br />

when young<br />

5–6 Linen Kurhessen:<br />

1.0cm–1.2cm Prussia:<br />

?<br />

10 in young plants,<br />

9 in adult plants<br />

first red, then brownish,<br />

young plants<br />

white<br />

Narrow, acute,<br />

crenate<br />

Impressed. Young ones<br />

with abundant white<br />

hairs, later deciduous;<br />

spines rigid<br />

Slightly obtuse Nearly obtuse<br />

Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

1.38–1.84cm Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

10 in young plants,<br />

9 in adult plants<br />

5–9 5–9<br />

Base red, the rest dark Pale Whitish<br />

Radial spine length Not indicated Not indicated 1.15–1.38cm 10–15mm 1–1.5cm<br />

Radial spine shape<br />

Central spine number<br />

Straight, the younger<br />

ones setose<br />

Young plant: 4-6<br />

Adult plant: 1<br />

Straight, younger<br />

ones setose<br />

Young plant: 4-6<br />

Adult plant: 1<br />

Straight Straight, radiating Straight<br />

Young plant: 4-6<br />

Adult plant: 1<br />

1 1<br />

Central spine shape Erect Erect Erect Straight Straight and erect<br />

Central spine colour Brownish Brown Brown, dark<br />

Central spine size<br />

Flower diameter<br />

Not topping the other<br />

ones<br />

2 Zoll Kurhessen:<br />

4.794cm Prussia:<br />

7.5324cm<br />

Not indicated Larger than radials<br />

2 Zoll Kurhessen:<br />

4.794cm Prussia:<br />

7.5324cm<br />

Perianth tube Not indicated Not indicated<br />

Tepal shape<br />

Narrow, with denticulate<br />

tip<br />

Narrow, with denticulate<br />

tip<br />

Grey-white with<br />

darker tip<br />

15–20mm, more often<br />

distinctive thicker<br />

Grey, with brown tips<br />

1.5–2cm<br />

5 cm Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

Sparsely covered with<br />

wool<br />

Linear, with denticulate<br />

tip<br />

Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

Tepal colour Translucent yellow Translucent yellow Yellow Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

Stamen filaments Red Red Red Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

Stigma colour Carmine Carmine Bright-red Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

Style colour Sulphur-coloured Sulphur-coloured Yellow Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

Stigma lobe number 10 10 10 Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

Shape and type of<br />

fruit<br />

Fruit covering<br />

Berry, oblong Berry, oblong Berry, oblong Not mentioned Not mentioned<br />

Smooth, distinguishing<br />

from the wool<br />

Smooth, distinguishing<br />