Herba Cana - Northeastern Illinois University

Herba Cana - Northeastern Illinois University

Herba Cana - Northeastern Illinois University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

Packera/Senecio<br />

(Packera: Named in 1976 by Askell and Doris B.M.<br />

Löve for <strong>Cana</strong>dian botanist John G. Packer; Senecio:<br />

From Latin senex, an old man, alluding to the white<br />

pubescence of many species, or the white pappus)<br />

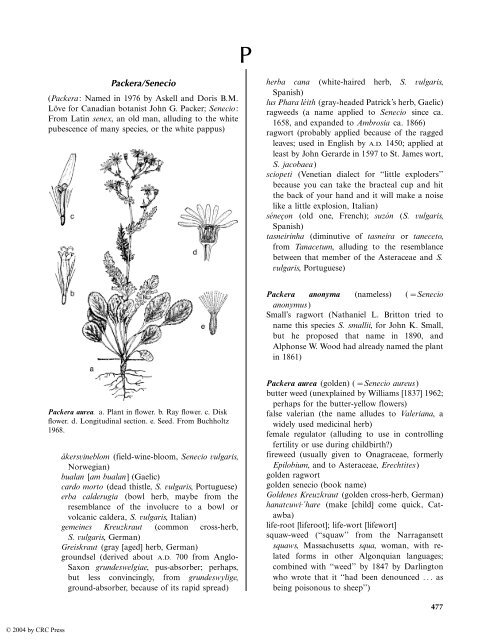

Packera aurea. a. Plant in flower. b. Ray flower. c. Disk<br />

flower. d. Longitudinal section. e. Seed. From Buchholtz<br />

1968.<br />

a˚kersvineblom (field-wine-bloom, Senecio vulgaris,<br />

Norwegian)<br />

bualan [am bualan] (Gaelic)<br />

cardo morto (dead thistle, S. vulgaris, Portuguese)<br />

erba calderugia (bowl herb, maybe from the<br />

resemblance of the involucre to a bowl or<br />

volcanic caldera, S. vulgaris, Italian)<br />

gemeines Kreuzkraut (common cross-herb,<br />

S. vulgaris, German)<br />

Greiskraut (gray [aged] herb, German)<br />

groundsel (derived about A.D. 700 from Anglo-<br />

Saxon grundeswelgiae, pus-absorber; perhaps,<br />

but less convincingly, from grundeswylige,<br />

ground-absorber, because of its rapid spread)<br />

P<br />

herba cana (white-haired herb, S. vulgaris,<br />

Spanish)<br />

lus Phara léith (gray-headed Patrick’s herb, Gaelic)<br />

ragweeds (a name applied to Senecio since ca.<br />

1658, and expanded to Ambrosia ca. 1866)<br />

ragwort (probably applied because of the ragged<br />

leaves; used in English by A.D. 1450; applied at<br />

least by John Gerarde in 1597 to St. James wort,<br />

S. jacobaea)<br />

sciopeti (Venetian dialect for ‘‘little exploders’’<br />

because you can take the bracteal cup and hit<br />

the back of your hand and it will make a noise<br />

like a little explosion, Italian)<br />

séneçon (old one, French); suzón (S. vulgaris,<br />

Spanish)<br />

tasneirinha (diminutive of tasneira or taneceto,<br />

from Tanacetum, alluding to the resemblance<br />

between that member of the Asteraceae and S.<br />

vulgaris, Portuguese)<br />

Packera anonyma (nameless) ( /Senecio<br />

anonymus)<br />

Small’s ragwort (Nathaniel L. Britton tried to<br />

name this species S. smallii, for John K. Small,<br />

but he proposed that name in 1890, and<br />

Alphonse W. Wood had already named the plant<br />

in 1861)<br />

Packera aurea (golden) ( /Senecio aureus)<br />

butter weed (unexplained by Williams [1837] 1962;<br />

perhaps for the butter-yellow flowers)<br />

false valerian (the name alludes to Valeriana, a<br />

widely used medicinal herb)<br />

female regulator (alluding to use in controlling<br />

fertility or use during childbirth?)<br />

fireweed (usually given to Onagraceae, formerly<br />

Epilobium, and to Asteraceae, Erechtites)<br />

golden ragwort<br />

golden senecio (book name)<br />

Goldenes Kreuzkraut (golden cross-herb, German)<br />

hanatcuwi·’hare (make [child] come quick, Catawba)<br />

life-root [liferoot]; life-wort [lifewort]<br />

squaw-weed (‘‘squaw’’ from the Narragansett<br />

squaws, Massachusetts squa, woman, with related<br />

forms in other Algonquian languages;<br />

combined with ‘‘weed’’ by 1847 by Darlington<br />

who wrote that it ‘‘had been denounced ... as<br />

being poisonous to sheep’’)<br />

477

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

478 Florida Ethnobotany<br />

unkun (English? a name unexplained by Millspaugh<br />

1892)<br />

When Wunderlin (1998) published his Guide to the<br />

Vascular Plants of Florida, he used the long-established<br />

genus Senecio, based on the Latin name of a plant<br />

used by Pliny. The name alludes to the white pubescence<br />

of many species or to the white hairs of the<br />

pappus. Later, Wunderlin and Hanson (2002) accepted<br />

several changes in the genera of Asteraceae and began<br />

using the genus Packera for a group of 60 to 65<br />

species, mostly in North America, with 16 in Mexico,<br />

and others in Siberia. Kartesz (1994) continued using<br />

Senecio in the broad sense, so both options are given<br />

here.<br />

Regardless of the name, the species contain potent<br />

pyrrolizidine alkaloids (e.g., senecionine), which cause<br />

liver damage if ingested (Lewis and Elvin-Lewis 1977,<br />

Lampe and McCann 1985). That damage occurs<br />

through acute venous occlusions in the liver (Budd-<br />

Chiari syndrome), and can lead to cirrhosis and, in<br />

some cases, death (Lampe and McCann 1985, Foster<br />

and Duke 1990).<br />

In spite of their toxic properties, some species were<br />

still being used externally in Europe in the 1970s as<br />

poultices for wounds and abscesses (OED 1971).<br />

Bown (1995) found that P. aurea still is grown in<br />

Belorussia, central Russia, and the Ukraine for the<br />

pharmaceutical industry.<br />

Plants in this group of Asteraceae have been used<br />

by people for thousands of years in both hemispheres.<br />

Famous species in Europe are S. cineraria, S. jacobaea,<br />

and S. vulgaris (Polunin 1969). Vickery (1995)<br />

found people still applying S. vulgaris to cuts, treating<br />

ague with it, and using it as a laxative. Senecio<br />

jabocaea was associated with witches and fairies<br />

in the British Isles and is known in Gaelic as<br />

buadhghallan buidhe [buaghallan, boholàun, boholàun<br />

buidhe] (buadh, virtuous, ghallan, branch, buidhe,<br />

yellow).<br />

In the Americas, the Catawba used P. anonyma to<br />

treat consumption (Moerman 1998). The Cherokee<br />

used P. aurea as a contraceptive and for heart trouble<br />

(Hamel and Chiltoskey 1975). The Iroquois used P.<br />

aureus for the blood, as a diaphoretic, to reduce fever<br />

in children, and to treat broken bones (Moerman<br />

1998).<br />

Porcher (1863) wrote, ‘‘It is said by [David]<br />

Schoepf to have been a favorite vulnerary with the<br />

Indians; the juice of the plant in honey, or the seeds in<br />

substance, are employed.’’ Millspaugh (1892) knew<br />

that the plants had been used by indigenous people to<br />

stop bleeding, as an abortivant, and a vulnerary. It was<br />

recommended for controlling bleeding in the lungs, for<br />

uterine problems, as a diuretic, pectoral, diaphoretic,<br />

and tonic.<br />

Bown (1995) still maintained that P. aurea is a<br />

bitter, astringent herb that is diuretic, stimulates the<br />

uterus, and controls bleeding. However, she added that<br />

it should be used by ‘‘qualified practitioners only,’’<br />

and that it is subject to legal restrictions in some<br />

countries. Duke et al. (2002), who typically give levelheaded<br />

recommendations, list P. aurea as ‘‘XXX’’*/<br />

not to be used (think of each X ‘‘as a skull and<br />

crossbones’’). Hocking (1997) noted that P. anonyma<br />

has been said to have antitumor properties, but gives<br />

no reference.<br />

Moerman (1998) found ten other species of<br />

Senecio and Packera being used by different tribes<br />

within North America. Thus, it would be surprising if<br />

other species (P. glabella, P. obovata, and P. paupercula)<br />

had not been used by indigenous tribes. However,<br />

of these, P. glabella has an enormous range in<br />

North America and no records have been found of<br />

anyone using it.<br />

Panicum<br />

(From the classical Latin name of bread, panis, or<br />

millet, panus; related to Akkadian panu, Italian pane,<br />

bread)<br />

cockspur (originally the spur on a cock or male<br />

chicken, used since at least the 1590s; awns on<br />

some grasses led to the comparison with the<br />

fowl)<br />

Hirse (German)<br />

millet (from Latin millium, having a thousand<br />

grains, French); miglio (Italian); milho (Portuguese)<br />

Panicum hemitomon (halved, from the somewhat<br />

one-sided spikes)<br />

cintha:câ:bî (snake tail replica, Mikasuki);<br />

cintha:cî (snake tail, Mikasuki)<br />

maiden-cane [maidencane] (perhaps meaning<br />

‘‘grass resembling harvest maiden,’’ from the<br />

old tradition of forming the last handful of<br />

wheat into the shape of a woman; harvest<br />

maiden also known as kirn-baby and kirn-doll,<br />

from the 1770s but surely much older as ‘‘kirn’’<br />

dates to the 1300s, USA)<br />

pahitoɬ piɬ î (pahi, grass, toɬ piɬ l, knees, Mikasuki);<br />

[pahitóɬ piɬ ó:cî] pahitórpiró:cî (pahi, grass, toɬ piɬ l,<br />

knees, oci, small, Mikasuki)

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

The Ethnobotany 479<br />

Panicum hemitomon. From Institute of Food and Agricultural<br />

Sciences.<br />

Panicum laxiflorum (loosely flowered) (as<br />

P. xalapense) ( /Dichanthelium laxiflorum)<br />

open-flower witch-grass [openflower witchgrass]<br />

(Florida)<br />

soft-tufted panic-grass [soft-tufted panicgrass]<br />

Panicum strigosum (with appressed hairs) (as<br />

P. polycaulon) ( /Dichanthelium strigosum)<br />

cofimássi (cufe, rabbit, em, its, vsse, dried leaves,<br />

Creek); cokfimasí (cokfí, rabbit, im, its, híssi,<br />

leaves, Koasati); cokfímpatâ:kî [tcokfwimpataki]<br />

(rabbit’s bed, Mikasuki)<br />

cushion-tufted panic-grass [cushion-tufted panicgrass]<br />

rough-hair witch-grass [roughhair witchgrass]<br />

(Florida)<br />

Hogan (1978) found pollen of Panicum hemitomon<br />

in the coprolites of the Glades people that she studied.<br />

As they were living beside vast stands of the windpollinated<br />

plants, that is no clear indication that they<br />

used the grass. However, being in a pre-Columbian<br />

context and having historical documentation of use is<br />

provocative. The Seminoles too know these formerly<br />

abundant grasses (Sturtevant 1955), and at least use<br />

them to the extent of ‘‘reading’’ the landscape. Where<br />

there is pahitóɬ piɬ ó:cî, they know that the water<br />

remains near a certain depth. That constitutes part<br />

of their knowledge of the landscape.<br />

Because of doubtful identifications, Moerman<br />

(1998) placed all the grasses used by the Creeks,<br />

Natchez, and Seminoles under Panicum sp. However,<br />

the species recorded by Sturtevant (1955) are reliably<br />

known. Since Sturtevant (1955) indicated that a third<br />

species was similarly used, perhaps others were used<br />

by the Seminoles’ relatives, the Creeks.<br />

The Creeks and Natchez used a Panicum leaf<br />

infusion for fevers, especially malaria (Swanton 1928a,<br />

Taylor 1940). Symptoms of those diseases are close<br />

enough to the Seminole malady called ‘‘Gopher<br />

Tortoise Sickness’’ (cough, dry throat, noisy chest)<br />

to suggest that the Creeks and Natchez used the same<br />

grasses. The Seminoles also used cokfímpatâ:kî for<br />

‘‘Rabbit Sickness’’ (muscle cramps) (Sturtevant 1955).<br />

The Cherokee used some Panicum, possibly more<br />

than one species, for padding inside their moccasins<br />

(Hamel and Chiltoskey 1975).<br />

Parietaria<br />

(Linnaeus based this on Latin parietis, a wall, in<br />

reference to its frequent occurrence there)<br />

bartram [bertram] (an English corruption of<br />

Greek pyrethrum, from pyros, fire; the name<br />

was originally given to Anacyclus pyrethrum or<br />

pellitory of Spain by at least 1578 with Henry<br />

Lyte’s translation of Dodoens’s Cruydeboek of<br />

1554; later the name became secondarily applied<br />

to Parietaria, because both were called pellitory)<br />

blidnesle (gentle nettle, Norwegian)<br />

Glaskraut (glass herb, German)<br />

lus a’ bhalla (wall herb, Gaelic)<br />

parietaria (from Latin parietis, Italian, Spanish);<br />

parietária (Portuguese); pariétarie (French); pellitory<br />

(from Latin parietis)<br />

Parietaria floridana (from Florida)<br />

herbe à murailles (wall herb, Haiti)<br />

herbe gras (fat herb, Haiti)<br />

paille à terre (country straw, Haiti)

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

480 Florida Ethnobotany<br />

Parietaria floridana. a. Section of plant. b. Flower, side view.<br />

c. Flower, longitudinally dissected. d. Fruit. e. Achene.<br />

f. Floral diagram. Drawn by Priscilla Fawcett. From Correll<br />

and Correll 1982.<br />

parietaria (pellitory, Dominican Republic); pariétarie<br />

(pellitory, Haiti); pariétarie capitee (pellitory<br />

with heads, Haiti); pariétarie sauvage (wild<br />

pellitory, Haiti); pellitory (Florida)<br />

thé del malheureux (tea for the unfortunate, Haiti)<br />

Newcomers to the New World were able to<br />

recognize this southeastern plant because they knew<br />

European ‘‘pellitory-of-the-wall’’ or ‘‘mind-your-ownbusiness’’<br />

(Paritaria judaica in western and southern<br />

Europe and P. officinalis in central and southern<br />

Europe). Parietaria officinalis was famous and was<br />

known in 16th-century English as parietorior or<br />

pellitoire of the wall, in German as Tag und Nacht<br />

(day and night), Sanct Peterskraut (St. Peter’s herb),<br />

Glaszkraut (glass herb), or Dutch glascruyt (glass<br />

herb). Keeping closer to the Latin, the French said<br />

parietaire or laparitoire, the Italians and Spanish<br />

parietaria. Old World people took their use from<br />

classical authors Dioscorides (fl. A.D. 40 /80), Galen<br />

(ca. A.D. 129 /ca. 199), and Aëtius (A.D. 527 /565), and<br />

used it for kidney stones, as a diuretic, and to treat<br />

hemorrhoids (Meyer et al. 1999). Finding a similar<br />

plant in the Americas, they used it largely for the same<br />

problems.<br />

In Hispaniola, fresh P. floridana is diuretic and is<br />

also used for painful hemorrhoids (Liogier 1974).<br />

Haitians consider an infusion of the plant a diuretic<br />

for use in treating angina and gout (Morton 1981).<br />

Parietaria is also used for erysipelas and earache.<br />

Parthenocissus<br />

(Jules Emile Planchon, 1823 /1888, combined Greek<br />

parthenos, virgin, and kissos, ivy, perhaps alluding to<br />

the unisexual flowers)<br />

Parthenocissus quinquefolia. Drawn by P.N. Honychurch.<br />

Jungfraurebe (virgin vine, German); vigne-vierge<br />

(virgin vine, French)<br />

vite del <strong>Cana</strong>dà (<strong>Cana</strong>da grape, Italian)<br />

Parthenocissus quinquefolia (with five leaflets)<br />

American ivy<br />

false grape; parrita cimarróna (little wild grape)<br />

five-leaves; l’herb à cinq feuilles (five-leaved herb,<br />

Houma, Louisiana)

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

The Ethnobotany 481<br />

ifá imittó (ifá, dog,im, its, ittó, tree, Koasati)<br />

ingtha hazi itai (ghost grapes; hazi, grapes,<br />

Omaha-Ponca)<br />

manido’bima’kwud (manido, spirit, Ojibwa)<br />

omakaski’bag (toad weed, Potawatomi)<br />

sa-tai-al-go (paint berries, Kiowa)<br />

vfala omat [afala oma] (vfala, poison ivy, omat,<br />

like, Creek)<br />

vigne-vierge (virgin vine, Quebec); Virginia [Virginian]<br />

creeper (‘‘creeper’’ is another word for<br />

climber or twiner)<br />

woodbine [woodbind, wild wood-vine] (originally<br />

a European term for Convolvulus and Hedera,<br />

dating to about A.D. 875, and alluding to the<br />

tendency of the climbers to wrap around others,<br />

USA)<br />

The first record of these vines in the New World is<br />

Jacques Philippe Cornutus’s Edera quinquefolia canadensis<br />

(five-leaved <strong>Cana</strong>dian ivy), published in his<br />

book <strong>Cana</strong>densium plantarum ... historia of 1635.<br />

Linnaeus knew this and several other sources. He had<br />

studied live plants at the Hortus Cliffortianus. Perhaps<br />

because he was influenced by Cornutus and others, he<br />

called the vines Hedera quinquefolia.<br />

Probably the first report of interaction of the plant<br />

and people was left by Capt. John Smith in 1624. He<br />

wrote that, in Virginia, there was a ‘‘kind of woodbind<br />

...which runnes vpon trees, twining it self like a<br />

Vine: the fruit eaten ... worketh ... in the nature of a<br />

purge.’’ In spite of Smith’s report, Yanovsky (1936)<br />

said that the fruit could be eaten raw, and the stalks<br />

were peeled and boiled for food. He reported those<br />

uses in Minnesota, Montana, and Wisconsin. One of<br />

them is wrong, and I doubt that it was Smith.<br />

Native people in the New World had long been<br />

familiar with the twiners. The plants were used by the<br />

Cherokee, Creeks, Houma, Iroquois, Jemez, Keres,<br />

Kiowa, Meskwaki, Montana tribes, Navajo, and<br />

Ojibwa (Densmore 1928, Moerman 1998). Most of<br />

these people used the plant as medicine, but they also<br />

made dye from it, and some claim to have eaten the<br />

roots. In the southeast, the Cherokee used an infusion<br />

against jaundice (Hamel and Chiltoskey 1975). The<br />

Houma used a hot decoction of stems and leaves to<br />

reduce swelling, to treat wounds, and against lockjaw<br />

(Speck 1941). The Creeks used it against venereal<br />

disease (Taylor 1940). Snow and Stans (2001) published<br />

a picture of the vine (p. 80), but gave no<br />

common name, or included it in the text. Some<br />

Seminoles still use this medicine.<br />

In Mexico, the bark has been used as an alterative,<br />

tonic, expectorant, and against dropsy; crushed leaves<br />

are a counterirritant, producing blisters when applied<br />

to the skin (Standley 1920 /1926). Early American<br />

physicians also used a tincture, which was sometimes<br />

called Decoctum ampelopsis or Infusum ampelopsis,<br />

reflecting an old scientific name, Ampelopsis quinquefolia<br />

(Millspaugh 1892). Not much seemed to be<br />

known about its chemistry in the 1890s, and the<br />

same is true today. Foster and Duke (1990) cryptically<br />

wrote, ‘‘Berries reportedly toxic,’’ although Capt. John<br />

Smith wrote the same in the 1620s. The leaves<br />

contain calcium oxylate and cause dermatitis in<br />

some people (Foster and Duke 1990, Foster and Caras<br />

1994), compounding the difficulty people have distinguishing<br />

between this and poison ivy (Toxicodendron<br />

radicans).<br />

Paspalidium<br />

(Diminutive of Paspalum, Greek paspalos, for millet;<br />

the genus was separated from Paspalum by Otto Stapf,<br />

1857 /1933)<br />

Paspalidium geminatum (twins or double) ( /P.<br />

paludivagum)<br />

akkotó:ɬ ka [akkotó:rka] (akkotorkv, usually Nelumbo,<br />

Creek; a comparison or a misuse)<br />

ciktohacî (cekto, snake, hvce, tail, Creek)<br />

Egyptian panicum (some consider the species<br />

native, like Allen 2003, while others think it<br />

was introduced from Egypt)<br />

kissimmee grass (‘‘kissimmee’’ was rendered as<br />

Cacema on the Moll Map of 1720 and Casseeme<br />

on William’s Map of 1837; the locality was not<br />

mentioned by Swanton in either 1939 or 1946;<br />

language and meaning unknown)<br />

pahitóɬ piɬ î [pahitórpirî] (pahi, grass, toɬ piɬ l, knees,<br />

because the stem is jointed, Mikasuki; this name<br />

is also used for Panicum hemitomon, which<br />

see)<br />

water panic grass (Florida)<br />

Pehr Forsska˚l called plants he found in Egypt<br />

Panicum geminatum in 1775. However, it was not until<br />

1919 that the species was transferred to Paspalidium in<br />

the Flora of Tropical Africa. Godfrey and Wooton<br />

(1979) considered the species native, while Crins<br />

(1991), Wunderlin (1998), and Diggs et al. (1999)<br />

thought it introduced. The problem is considered<br />

unsolved by Gerald Guala (personal communication,<br />

Oct. 2003).<br />

The Seminoles use a decoction of the plant to treat<br />

‘‘Snake Sickness’’ (itchy skin) (Sturtevant 1955).

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

482 Florida Ethnobotany<br />

Paspalum<br />

(From Greek paspale or paspalos, meal or millet)<br />

Paspalum conjugatum. Drawn by Mary Wright Gill. From<br />

Hitchcock and Chase 1950.<br />

Paspalum conjugatum (joined together)<br />

ahan toom (elote-roasting ear grass, Huastec)<br />

bed grass (Bahamas)<br />

cañamazo amargo (big sour cane, Cuba); cañamazo<br />

[hembra] ([female] big cane, Dominican<br />

Republic)<br />

capim de marreca (mallard hen grass, Marajó,<br />

Brazil); capim gorda (fat grass, Marajó, Brazil)<br />

gengibrillo (little ginger)<br />

grama (grass, Dominican Republic); grama de<br />

antena (antenna grass, Central America); grama<br />

comun (common grass)<br />

herbe sûre [z’herbe sûre] (sour herb, Haiti);<br />

Jamaican sour grass (Jamaica); sour-grass; yerba<br />

agria (sour-herb)<br />

horquilla (little hairpin, Central America); horquetilla<br />

[blanca] ([white] little hairpin, Puerto Rico);<br />

pasto horqueta (hairpin grass)<br />

paja de panela (sugar grass)<br />

sarataya (Siona, Ecuador)<br />

sour paspalum (a book name)<br />

tarurco [torurco, toro-urco]<br />

trencilla (Central America)<br />

turvará (indigenous name, Costa Rica, western<br />

Ecuador)<br />

Around the edges of wetlands where it is neither<br />

wet enough to be marsh nor dry enough to be<br />

pinelands, there is an intermediate zone locally known<br />

as wet prairie. These areas dominated by graminoid<br />

plants are where Paspalum conjugatum most often is<br />

encountered. The flowering scapes stand above the<br />

mostly prostrate stems and leaves, and the twobranched<br />

inflorescences have reminded people of<br />

horquillas (hairpins). Occasionally in Paspalum we<br />

find a dark mass of mycelia that has replaced the<br />

seeds, and we know that an ergot fungus (Claviceps)<br />

has infected the grass. Those fungi contain LSD-like<br />

chemicals and can cause problems or be used to relieve<br />

maladies. I must wonder if these grasses were used for<br />

medicines because of this fungal infection.<br />

Judging from the names of this species throughout<br />

its range, people have had strong feelings either for or<br />

against this grass. Some pastoral groups dislike the<br />

grass because it does not provide good forage for their<br />

animals*/ostensibly because of its sour taste. Others<br />

praise it highly as food for their animals. For people,<br />

though, the grass is sometimes important in remedies.<br />

In Cuba, cañamazo amargo is used as a bath for<br />

patients with malaria (Roig 1945). People in Trinidad<br />

use a decoction to relieve fever, flu, pleurisy, pneumonia,<br />

and fatigue (Wong 1976). The Bahamians make a<br />

medicine for tuberculosis with prickly pear (Opuntia)<br />

and wood ashes (Eldridge 1975). The grass is also<br />

medicinal in Belize (Balick et al. 2000).<br />

Passiflora: Passion-Flower<br />

(Linnaeus reversed the Latin Flos passionis; crucifixion<br />

flower, originally used by Nicolas Monardes)<br />

Virtually every discussion about passion-flowers<br />

tells of the comparison between the passion of the<br />

crucifixion of Christ and the flowers. Jesuit priests<br />

made that analogy in their efforts to convert the New<br />

World people. Presumably, the ‘‘leaf symbolizes the<br />

spear. The five petals and five sepals the ten apostles<br />

(Peter who denied, and Judas who betrayed, being<br />

omitted). The five anthers, the five wounds. The<br />

tendrils, the scourges. The column on the ovary, the<br />

pillar of the cross. The stamens, the hammers. The<br />

three stigmas, the three nails. The filaments within

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

The Ethnobotany 483<br />

Passiflora suberosa. Drawn by P.N. Honychurch.<br />

the flower, the crown of thorns. The calyx, the glory<br />

or nimbus. The white tint, purity. The blue tint,<br />

HEAVEN’’ (Coffey 1993). What most accounts do<br />

not add is the historical sequence behind that story.<br />

Nicolas Monardes was perhaps the first to use the<br />

Latin term Flos passionis (flower of the crucifixion) in<br />

1582. Since that story and the plant were not part of<br />

John Frampton’s ([1577] 1925) translation, Englishspeaking<br />

people were rarely aware of Monardes’s role.<br />

Supposedly, the same species was brought to Europe<br />

by Jac Boccio in 1610, and that introduction may have<br />

been the source of cultivated plants in England,<br />

Holland, and Sweden (Svanidze et al. 1974).<br />

The same passion-flower, later named P. incarnata,<br />

was mentioned by Strachey ([1612] 1953) on the James<br />

River of Virginia: ‘‘Here is a Fruict by the Naturalls<br />

called a Maracock this groweth generally lowe and<br />

creepeth in a manner amongest the Corne ... yt is of<br />

the bignes of a Queene-apple, and hath many azurine<br />

or blew kernells, like as a Pomegranett, and it<br />

bloometh a most ssweet and delicate flower, and yt is<br />

a good Sommer Cooling fruict, and in every field<br />

where the indigenous people plant their Corne be<br />

Cart-loades of them.’’ His original notes on the<br />

Powhatan used maracah (Harrington 1955). That<br />

same year Capt. John Smith reported that the<br />

indigenous people planted ‘‘Maracocks, a wild fruit<br />

like a lemmon, which also increase in fruit’’ (Coffey<br />

1993). Subsequently, herbalist Gaspar Bauhin recorded<br />

the species in 1623. Parkinson ([1629] 1976)<br />

wrote that the plant ‘‘Maybe called in Latine, Clematis<br />

Virginiana; in English, the Virgin or Virginia Climer;<br />

of the Virginians, Maracoc; of the Spanish in the West<br />

Indies, Granadillo, because the fruit ... is in some<br />

fashion like a small Pomegranate on the outside.’’<br />

However, it was the name Granadilla hispanis, flos<br />

passionis italis (little Spanish pomegranate, Italian<br />

passion flower) published by Francisco Hernández in<br />

his book of 1651 that was the earliest firsthand record<br />

Linnaeus had as the basis for Passiflora in 1753. Not<br />

only did Linnaeus have the description and drawing<br />

from Hernández, but he also knew that the plants had<br />

been cultivated in England from the 1600s. Indeed,<br />

Linnaeus had studied the live plants at the Hortus<br />

Cliffortianus (Holland) and Hortus Uppsaliensis (Sweden).<br />

All these names had been applied to the species<br />

that Linnaeus called P. incarnata (flesh-colored). He<br />

was mistaken about the flower color because they are<br />

blue.<br />

The Latin Flos passionis became flor de la pasión<br />

(Spanish), fleur de la passion (French), flor da paixão<br />

(Portuguese), and passion-flower as generic equivalents<br />

of the genus Passiflora. The apparent lone<br />

exception to these names is in Puerto Rico where the<br />

genus is called parcha (from palcha, Quechua). Today<br />

parcha is mostly associated with the introduced South<br />

American P. edulis. Probably the plant and its name<br />

were introduced at the same time from Peru where<br />

now P. edulis is called maracuya.<br />

The names maricock and maracocks gave rise to<br />

maracoc, maycock, maypop (Alabama, North Carolina),<br />

mayapple (Alabama, North Carolina), Mollypop<br />

(Alabama, North Carolina), pop-apple (North<br />

Carolina), apricot (North Carolina), and apricot-vine<br />

(Texas). All of these names are supposedly derived<br />

from mahcawq [mäkak, mä’kâwk] (Powhatan), akin to<br />

machkak (Menomini), mäkäk (Cree, Ojibwa), and<br />

ma’ka’kwi (Fox). Although similar, there seems to be<br />

no relation to Tupí mboruku’ya or maraú-yá, in<br />

Portuguese maracujá, and maracuya in Spanish,<br />

names for P. edulis (Gerard 1907).<br />

Passiflora incarnata is also known as granadilla<br />

(little pomegranate, Texas, Florida fide Williams<br />

[1837] 1962), Holy-Trinity flower (Texas), pasionaria<br />

(of the crucifixion, Texas), passion-vine (North Carolina),<br />

and purple passionflower (Florida). Opako is<br />

the Alabama name, and it is almost identical to the<br />

Koasati apakó, Muskogee opvkv [opv’kv], and Miccosukee<br />

opakî. Probably belonging here is làanasi (laana,<br />

yellow, osi, suffix meaning extremely, Alabama). The<br />

plant designated by the Alabama name is described as<br />

having a ‘‘small sweet melon, smells like a honeydew,<br />

makes the mouth itchy, size of an orange; a vine with a<br />

fruit similar to passion fruit (if one eats too much of it,<br />

it will blister the tongue and mouth)’’ (Sylestine et al.<br />

1993). The species ranges from Virginia to Missouri,<br />

south to Florida and Texas and Bermuda, and it is<br />

introduced farther north in the United States.<br />

In addition to eating the fresh fruits (uwa’ga), the<br />

Cherokee made a social drink of them, mixing the

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

484 Florida Ethnobotany<br />

juice with cornmeal as a thickener. That would be a<br />

drink akin to horchata in Latin America. Most<br />

surprising is that the Cherokee also parboiled and<br />

then fried the leaves in hot grease as a potherb (Hamel<br />

and Chiltoskey 1975).<br />

The Cherokee and other indigenous people used P.<br />

incarnata as medicine. A compound infusion of the<br />

roots was used to treat boils, and roots were used to<br />

stop inflammation of wounds. Infants were given<br />

infusions of the roots to aid in weaning, and it also<br />

was used to relieve earache (Hamel and Chiltoskey<br />

1975). The Houma called it chassepareille incarnata<br />

(flesh-colored saw brier), and took an infusion of the<br />

roots as a blood tonic (Speck 1941). Whole plants have<br />

traditionally been used in a tea as an antispasmodic<br />

and as a sedative for neuralgia, epilepsy, restlessness,<br />

painful menses, insomnia, and tension headaches.<br />

Linnaeus ([1753] 1957) also published the Florida<br />

species P. lutea (yellow passionflower, Florida), P.<br />

multiflora (whiteflower passionflower, Florida; fruta<br />

de perro, dog fruit, Cuba; pasionaria vainilla, vanilla of<br />

the crucifixion, Cuba), and P. pallens (pineland<br />

passionflower, Florida). Similarly, Linnaeus named<br />

P. sexflora and P. suberosa, which are better known<br />

within the Caribbean.<br />

Passiflora sexflora grows in Florida, the Greater<br />

Antilles to Puerto Rico, and from Mexico to Panama<br />

and Colombia. In those areas the plant is known as<br />

ala de murcielago or bat wing (Jamaica), duck foot<br />

(Jamaica), duppy pumpkin (Jamaica), goat foot (Jamaica,<br />

Florida), and pasionaria de cerca (fence passion<br />

vine, Cuba). Guatemalans make a sedative<br />

preparation of the flowers for nerves, insomnia, and<br />

diarrhea.<br />

Even more noted is P. suberosa, native from<br />

southern Florida to southern Texas to northern South<br />

America and the West Indies, introduced into the Old<br />

World. That species like all the others has edible fruits,<br />

although they are smaller than most. The edible fruits<br />

gave rise to the names baleeyail an ’its’aamal (deer<br />

watermelon, Huastec, San Luis Potosí), huevo de gallo<br />

(rooster egg, Cuba), juniper berry (Bahamas), meloncillo<br />

(little melon, Cuba), morita (blackberry, Dominican<br />

Republic), parcha yedra (ivy passionfruit, Puerto<br />

Rico), parchita de culebra (snake’s little passion-fruit,<br />

Venezuela), and wild pumpkin (Caymans). Fruits are<br />

also used to make black ink as noted by the names<br />

indigo berry (Virgin Islands), ink berry (Virgin<br />

Islands), and ink vine (Barbados).<br />

There are always names that are at odds with<br />

others. Passiflora suberosa is called corky passionflower<br />

in Florida because some scholar simply translated<br />

the Latin name. In Yucatán, the Maya say<br />

kansel-ak (kants’il, like cotton, ak, vine). Supposedly,<br />

it is called that because it is covered with trichomes<br />

like cotton, but most Florida plants are glabrous. In<br />

Hispaniola it is leontafia (lion’s aguardiente or whiskey)<br />

or tidiane (little Diane).<br />

When I first experienced juice from maracujá in<br />

Belém, Brazil in 1969, I was told that it was good to<br />

drink with dinner because it aided digestion and<br />

calmed the nerves. At the time, I drank it because it<br />

tasted good, but I could not really notice the effects.<br />

Subsequently, I discovered that several species<br />

are considered calmants or even intoxicants (Fellows<br />

and Smith 1938, Speroni and Minghetti. 1988, Medina<br />

et al. 1990, Solbakken et al. 1997, Dhawan et al.<br />

2001a,b,c). Some experiments support the tranquilizing<br />

conclusion, while others do not (Coleta et al. 2001,<br />

Volz 2001). One other caveat is that the commercial<br />

extract is possibly toxic, at least in some individuals<br />

(Fisher et al. 2000). However, most results indicate<br />

that plant extracts are mildly sedative, reduce blood<br />

pressure slightly, and decrease motor activity.<br />

In addition to the supposed sedative effects of<br />

Passiflora, several others are known, including as an<br />

adjuvant agent in the management of opiate withdrawal,<br />

and as an antibacterial, anticonvulsant, antifungal,<br />

and antioxidant (Nicolls et al. 1973, Medina<br />

et al. 1990, Akhondzadeh et al. 2001, Murcia et al.<br />

2001, Taglioli et al. 2001). Perhaps the most surprising<br />

result was in neutralization of hemorrhage from the<br />

fer-de-lance (Bothrops atrox) venom (Otero et al.<br />

2000), although bleeding decreased only 25%.<br />

Chemicals have been identified from several species,<br />

including P. edulis, P. foetida, P. incarnata, and P.<br />

quadrangularis. Compounds found are the alkaloid<br />

passiflorine, benzylic beta-D-allopyranosides 1 and 2,<br />

which are representatives of a rare class of natural<br />

glycosides, flavonoids, cycloartane triterpenoids and<br />

six related saponins, harmane and harmine, oxygenated<br />

monoterpenoids, and passifloricins (polyketides<br />

alpha-pyrones) (Lutomski and Wrocinski 1960, Bennati<br />

1971, Morton 1981, Osorio et al. 2000, Yoshikawa<br />

et al. 2000a,b, Christensen and Jaroszewski 2001,<br />

Echeverri et al. 2001). Harmaline and harmine have<br />

been used to treat Parkinson’s disease (Swerdlow<br />

2000).<br />

In the 1960s, it was uncommon to find passionfruit<br />

juice in groceries, even in mixtures. Then a<br />

television commercial made ‘‘passion-fruit’’ an everyday<br />

word because it was an ingredient (minor) in<br />

‘‘Hawaiian punch.’’ The ad showed one cartoon<br />

character ‘‘punching’’ another when they said they<br />

wanted the drink. Everyone laughed at the catchy<br />

phrase, although few realized what a passion-fruit was.<br />

Botanists knew it was Passiflora, and somehow we felt<br />

smug knowing that bit of trivia.

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

The Ethnobotany 485<br />

Pavonia<br />

(Antonio José Cavanilles named this for José Antonio<br />

Pavón y Jimenez, 1754 /1844, a Spanish explorer who<br />

toured Chile and Peru with Hipolito Ruiz López and<br />

Joseph Dombey)<br />

Pavonia paludicola (swamp-loving) ( /P. spicata)<br />

cadillo de ciénaga (marsh sticker, Puerto Rico)<br />

cotton (Belize); wild cotton (Belize)<br />

gombo-mangle (mangrove okra, Guadeloupe,<br />

Martinique)<br />

kayuwaballi (kayuwa, mahoe or Hibiscus tiliaceus,<br />

balli, resembling, Arawak, Suriname)<br />

mahot mangle [mare] (mangrove [ocean] fiber tree,<br />

Taino and French, Guadeloupe, Martinique);<br />

mahuat (fiber tree, Taino, French Antilles);<br />

majagüilla (little fiber tree, Hispanized Taino,<br />

Cuba, Hispaniola); smaller mahoe (Jamaica)<br />

mangrove mallow (Guadeloupe, Martinique)<br />

sunabao (Guadeloupe, Martinique)<br />

swamp bush (Bahamas, Puerto Rico)<br />

Pavonia was created in 1786 by the director of the<br />

botanical garden in Madrid, Cavanilles (1745 /1804).<br />

However, it was not until 1989 that Dan Nicolson and<br />

Paul Fryxell described P. paludicola from the Lesser<br />

Antilles. That species brought the genus to a total of<br />

150 species found in tropical and warm regions of the<br />

world (Mabberley 1997).<br />

In the French Antilles, the leaves are applied to<br />

inflammations, boils, and abscesses (Morton 1981). In<br />

Haiti, an infusion is gargled for tonsillitis. Taken<br />

regularly, it is laxative.<br />

Pectis<br />

(From Latin pecten, pectinis, a comb, referring to the<br />

bristles along the margins of the leaves or the papus)<br />

Pectis prostrata (lying flat)<br />

cominillo [tomillo] (little dwarf, Venezuela); comino<br />

de piedra [de sabana, rústico] (stone [savanna,<br />

wild] dwarf, Venezuela)<br />

contra-yerba (herb against, typically meaning that<br />

it can be used to treat any malady)<br />

hierba de gallina (chicken herb); hierba de chinche<br />

(bedbug herb)<br />

romero macho (wild [male] rosemary, Puerto Rico)<br />

tebenque [tebenki, tebink, theebink] (probably<br />

Taino, Cuba); tebink moge (probably Taino,<br />

Cuba?)<br />

zacato-coche (car grass; probably because it is<br />

common on roadsides)<br />

Pectis prostrata has been reported from a number<br />

of places in the Caribbean, but there are indications<br />

that those are misidentifications. For example, the<br />

Flora of Cuba reported the plants from Jamaica, but<br />

Adams (1972) could not verify that they had ever been<br />

there. Similarly, Morton (1981) recorded medical use<br />

in Puerto Rico, but Liogier and Martorell (1982) do<br />

not include the species. TROPICOS lists specimens<br />

from Texas, Mexico (Chiapas, Tabasco, Yucatán),<br />

Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras,<br />

Nicaragua, Panama, and Ecuador.<br />

Maybe the true distribution is less important for<br />

ethnobotanical comments because people often do not<br />

distinguish species. In Venezuela, for example, both P.<br />

ciliaris and P. prostrata have the same names (Pittier<br />

1926). Perhaps that is because the aromatic traits of<br />

both are similar.<br />

Pectis prostrata has been taken to stop diarrhea,<br />

dispel flatulence, as an emmenagogue, and for venereal<br />

diseases in Venezuela (Pittier 1926). In Jamaica and<br />

Puerto Rico, it is taken for colds and tuberculosis<br />

(Morton 1981). The species is used as a medicine in<br />

Belize (Balick et al. 2000). Hocking (1997) reported<br />

that it had been used to treat colds and tuberculosis, to<br />

expel flatulence, and as an emmenagogue.<br />

Pedicularis<br />

(Named from Latin pediculus, a louse, because Europeans<br />

believed that cattle or sheep feeding where P.<br />

palustris grew became covered with lice; also herba<br />

pedicularis, lousewort, because it was used to kill lice)<br />

kallgra˚s (kall, cold?, gra˚s, grass, Swedish)<br />

Läusekraut (louse herb, German)<br />

myrklegg (myr, bog,klegg, gadfly, Norwegian)<br />

pédiculaire (French); pediculare (Italian)<br />

riabhach (gray or grizzled, Gaelic)<br />

Pedicularis canadensis (of <strong>Cana</strong>da)<br />

beefsteak-plant (Long Island)<br />

betony [betong, beton lousewort, head-betony]<br />

(‘‘betony,’’ from Latin betonica, which Pliny,<br />

A.D. 23 /79, said was a Gaulish name; betonica,<br />

from vettonica, derived from Vettones, people of<br />

Lusitania, originally applied to Stachys officinalis,<br />

New York); wood-betony (‘‘wood’’ meaning<br />

growing wild, as opposed to the cultivated<br />

betony, Stachys officinalis)<br />

cagacka’ndawesoanûk (flying squirrel tail, Potawatomi)<br />

chickens’-heads (Long Island)

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

486 Florida Ethnobotany<br />

Pedicularis canadensis. a. Habit. b. Flower. c. Stamen.<br />

d. Pistil. e. Fruit. Drawn by Vivian Frazier. From Correll<br />

and Correll 1972.<br />

[<strong>Cana</strong>dian, common, early, early fern-leaf] lousewort<br />

(‘‘louse’’ from a Teutonic base-word, as Old<br />

English lús, with cognates in German Laus,<br />

Danish and Swedish lus; first applied to Helleborus<br />

in the 1540s by Leonard Fuchs, as<br />

Laüszkraut, and later to Pedicularis by John<br />

Gerarde in 1597); lousewort-foxglove<br />

snaffles (presumably from ‘‘snuffles’’ or ‘‘sniffles,’’<br />

a nasal catarrh, used since the 1820s; a local<br />

name in England, usually applied to Rhinanthus,<br />

also in the Orobanchaceae, formerly Scrophulariaceae;<br />

cf. Coffey 1993)<br />

Linnaeus included Sweden’s Pedicularis in his<br />

Flora Oeconomica of [1749] 1979. When he published<br />

Species Plantarum in 1753, all of its 14 species were<br />

Old World plants. It was not until 1767 when Linnaeus<br />

published Mantissa Plantarum that he gave us P.<br />

canadensis, based on a collection by his student Peter<br />

Kalm in <strong>Cana</strong>da.<br />

People of the northeastern United States had<br />

known about this Pedicularis and other species for a<br />

long time by the 1760s. About 1750, Jane Colden<br />

wrote concerning what is now P. canadensis: ‘‘This<br />

pedicularis is call’d by the country people Betony.<br />

They make a Thee [tea] of the leaves, et use it for the<br />

fever & ague et for sickness of the stomach’’ (Colden<br />

in Coffey 1993). Settlers may have known about<br />

medicines from Old World species, or they may have<br />

learned from the indigenous tribes.<br />

Moerman (1998) recorded use among eight tribes.<br />

The Catawba made an infusion of roots to treat<br />

stomach problems. The Cherokee treated dysentery,<br />

coughs, and stomachaches with it (Hamel and Chiltoskey<br />

1975). They and the Iroquois also rubbed an<br />

infusion of roots on sores. The Iroquois treated<br />

women’s menstrual problems, heart troubles, and<br />

bleeding tuberculosis with the plants. The Menomini<br />

used it as a love charm. The Meskwaki treated<br />

external sores and tumors, and also made a love<br />

medicine with it (King 1984). The Mohegans used an<br />

infusion of leaves to induce abortion. The Ojibwa used<br />

a root infusion to counteract anemia, to treat stomach<br />

ulcers, sore throats, and as a love potion. The Forest<br />

Potawatomi used the roots as a physic, while the<br />

Prairie Potawatomi used the roots to reduce both<br />

internal and external swelling (Smith 1933).<br />

The Menomini and Potawatomi mixed lousewort<br />

with other plants to fatten their horses. Both the<br />

Cherokee and Iroquois ate the leaves and stems,<br />

sometimes cooking and seasoning them with salt,<br />

pepper, and butter (Yanovsky 1936).<br />

In the 1750s some Europeans still believed that<br />

cattle or sheep feeding where P. palustris grew became<br />

covered with lice. By the 1900s, others had totally<br />

changed views. Vickery (1993) recorded that people in<br />

the Shetland Islands called P. vulgaris ‘‘bee-sookies’’<br />

or ‘‘honey-sookies’’ because of its ‘‘nectar-filled<br />

flower-tubes,’’ which children sucked for their sweet<br />

flavor.<br />

Pediomelum<br />

(Per Axel Rydberg, 1860 /1931, segregated these<br />

plants from Psoralea with Greek pedion, field, and<br />

melon, an apple or fruit)<br />

Pediomelum canescens (grayish-pubescent) ( /Psoralea<br />

canescens)<br />

buck-horn [buck-thorn] (‘‘buck-thorn’’ is now<br />

applied to several genera, but was applied to<br />

Rhamnus catharticus by Dodoens in 1554; the

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

The Ethnobotany 487<br />

Latin cervi spina was applied to Rhamnus by<br />

Valerius Cordus, 1514? /1544)<br />

buckroot (known by this name in 1765 when John<br />

Bartram visited the Carolinas, Berkeley and<br />

Berkeley 1982)<br />

hoary scurfpea (‘‘scurf’’ is dry, scaly skin, especially<br />

on the head; probably from Old English<br />

scurf; akin to Swedish skorv, Danish skurv,<br />

Dutch schurft, and German Schorf)<br />

owá:lá:rî: ínsawá:kî (Sturtevant wrote ‘‘prophets’<br />

[plural; singular, owá:lî] coconut,’’ Mikasuki;<br />

‘‘owá:lî’’ is also translated as ‘‘wise-man,’’ ‘‘magician,’’<br />

or in Creek, as ‘‘knower’’); owa:lâlki<br />

insawkô (owalv, knower, em, his, svokv, rattle,<br />

Creek; the ‘‘coconut,’’ Cocos nucifera, is talasvokv)<br />

These herbs are restricted to parts of Virginia,<br />

Georgia, Florida, and Alabama (Radford et al. 1968).<br />

Because of their limited range, not much has been<br />

written about them, yet the Seminoles knew and used<br />

them as late as the 1950s (Sturtevant 1955). Moreover,<br />

they were familiar with the restricted range of the<br />

plants in Florida, noting that they did not grow south<br />

of Punta Gorda. They would make special trips into<br />

the area where the plants grew to obtain stocks of the<br />

roots to dry for use in medicine. Hedrick (1919) and<br />

Yanovsky (1936) say the roots have been eaten in the<br />

southern states.<br />

According to Josie Billie, one of Sturtevant’s<br />

collaborators, these legumes were analgesic when the<br />

warmed root was applied externally. To treat rheumatism,<br />

they took a root, dipped it in water, warmed it<br />

over the fire, and then pressed it against the sore spots.<br />

They considered it strong and expected the pain to be<br />

gone by the next morning. In addition, the roots were<br />

used in a medicine to treat colds and coughs.<br />

Sturtevant (1955) gave a lengthy account of his<br />

personal experience treating his own cold, and he<br />

was convinced it helped.<br />

Neither Foster and Duke (1990) nor Duke (2002)<br />

even mention the genus Pediomelum. Under Psoralea,<br />

Hocking (1997) says that this species has been used to<br />

treat gastric distress.<br />

Peltandra<br />

(Rafinesque named this with Greek pelte, a shield and<br />

andros, stamens)<br />

Peltandra virginica (from Virginia)<br />

[green] arrow [arum] (USA)<br />

ocfô (Creek); okõ:nî (Mikasuki)<br />

Peltandra virginica. a. Habit. b. Outline of leaf. c. Spadix.<br />

d. Berry (submersed). Drawn by Vivian Frazier. From Correll<br />

and Correll 1972.<br />

Pfeilaronstab (arrow arum stick, German)<br />

takwahahk (Capt. John Smith wrote the Powhatan<br />

name as tockwhogh, tocknough, and tockawhoughe.<br />

He said that it was the ‘‘chief root<br />

they have for food ... like a flag in low muddy<br />

freshes ... of the greatness and taste of potatoes<br />

...raw it is not better than poison ...roasted ...<br />

in summer they use this ordinarily for bread.’’<br />

Strachey wrote in [1612] 1953 that it was a<br />

‘‘bread made of a wort called taccahoappoans.’’<br />

Siebert 1975 considered the root to be /*takw-/,<br />

to pound fine, beat to a powder. The word<br />

written by Strachey includes the element appoans,<br />

which became ‘‘pone’’ in English; see also<br />

Zea); cognates include takáham (Delaware);<br />

takwaham (Cree); takwahamwa (Miami); takwham<br />

(Nipmuck-Pocumtuck); taw-ho [tawho, tawhim,<br />

tawhim, tuckah] (Delaware, New Jersey);<br />

tquogh (Mohegan); tukwhah (Shawnee); nitakhwa<br />

(‘‘I pound him for bread,’’ Shawnee);<br />

otakwaʔa·n (Ojibwa)

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

488 Florida Ethnobotany<br />

tuckahaw (according to Romans [1775] 1961, there<br />

was a Chickasaw town named for this plant, and<br />

using the Algonquian word)<br />

tuckahoe [tockwhogh, tockawhoughe, taw-ho]<br />

(from Powhatan, Virginia); coscúshaw (Carolina<br />

Algonquians; see also Geary 1955)<br />

[Virginian] wake robin (New England)<br />

Although there is considerable confusion about<br />

the original identify of tuckahoe, it has become<br />

associated with Peltandra since being discussed by<br />

Kalm ([1753 /1761] 1972), who had personal knowledge<br />

of the plants and the people using the name. That<br />

Powhatan word is related to petukqunneg (cake of<br />

bread, from petukqui, bread, pitikwah, made round,<br />

Cree). The distribution of the words presumably<br />

corresponds to part of the range of usage. However,<br />

most of these terms were transferred to maize when it<br />

was introduced, and that has complicated the situation.<br />

The first record of the indigenous use of these<br />

roots is in 1612 when Capt. John Smith wrote, ‘‘In<br />

Iune, Iulie and August they feede vpon the rootes of<br />

Tockwough, berries, fish and green wheat [maize]’’<br />

(OED 1971). Strachey recorded the plant and name<br />

the same year. The Seminoles also use the plant for<br />

food (Sturtevant 1955). Tull (1999) indicated that long<br />

periods of drying (sometimes months) and baking are<br />

necessary to render the acrid roots palatable. Both<br />

roots and fruits were eaten after detoxification.<br />

Methods of preparing them are given by Fernald et<br />

al. (1958).<br />

Harriot ([1590] 1972) had recorded another name<br />

and use among his list of fruits. He called them<br />

sacqvenvmmener, and not long afterward Strachey and<br />

Capt. John Smith called them ocoughtanamins. Harriot<br />

([1590] 1972) wrote that sacqvenvmmener were ‘‘a<br />

kinde of berries almost like vnto capres [capers,<br />

Capparis] but somewhat greater which being grow<br />

together in clusters vpon a plant or herb that is found<br />

in shallow waters: being boiled eight or nine hours<br />

according to their kind are very good meate and<br />

holesome, otherwise if they be eaten they will make a<br />

man for the time franticke or extremely sicke.’’ Smith<br />

thought they should be boiled half a day (Swanton<br />

1946).<br />

Yanovsky (1936) may have confused Orontium<br />

with Peltandra. Still, he listed Peltandra as having been<br />

eaten in all the southeastern states, and in New York,<br />

Pennsylvania, and Virginia, a distribution agreeing<br />

with its Algonquian names.<br />

Moerman (1998) indicates that the Nanticoke of<br />

Delaware grated the roots in milk and gave it to babies<br />

for some unstated medical reason.<br />

Penstemon<br />

(From Greek pente, five, and stemon, stamen, referring<br />

to the four fertile stamens and one sterile<br />

staminode)<br />

Penstemon laevigatus (smooth)<br />

[eastern smooth, foxglove, hairy] beard-tongue<br />

Europeans were familiar with Digitalis when they<br />

arrived in the New World, but here they found plants<br />

somewhat different from that old medicinal herb.<br />

When Casimir Christoph Schmidel (1718 /1792), a<br />

German physician at Erlangen, was working with<br />

plants grown in Kew Gardens outside London, he<br />

decided that the American plants should have a<br />

distinct name. He called them Penstemon in 1763<br />

because of their androecial arrangement. The genus<br />

now has grown to 250 species, with all but one<br />

confined to North America (Mabberley 1997).<br />

One of the species discovered after Schmidel was<br />

P. laevigatus. This herb, also described from plants<br />

grown at Kew, was named by William Aiton in 1789,<br />

and the specimen he used to name the species is in the<br />

Fothergill collection at the British Museum of Natural<br />

History. Smooth beard-tongue ranges from New<br />

Jersey, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia south to<br />

Florida (Gadsden and Jackson Counties), and west<br />

into Alabama and Mississippi.<br />

Not much information is available about this<br />

plant. The Cherokee used an infusion of P. laevigatus<br />

to stop cramps (Hamel and Chiltoskey 1975). This is<br />

probably the same species used by the Creeks and<br />

Natchez for colds, coughs, consumption, and whooping<br />

cough (Swanton 1928a).<br />

Porcher (1863), Millspaugh (1892), Vogel (1970),<br />

and Foster and Duke (1990) do not mention the genus.<br />

However, other Penstemon species were used by the<br />

Iroquois, Kiowa, Lakota, Pawnee, and several tribes<br />

farther west. Moerman (1998) found records of 23<br />

other species being used.<br />

Some Penstemon contain iridoid glycosides, especially<br />

catapol, and both moths and butterflies have<br />

adapted to sequester and use those compounds. The<br />

inchworm and looper moths Neoterpes graefiaria and<br />

Meris alticola take catapol from Penstemon, and the<br />

Arachne checkerspot butterfly (Polydryas arachne)<br />

also uses it.<br />

Pentalinon<br />

(Friedrich S. Voigt, 1781 /1850, named this with Greek<br />

pente, five, and linon, rope, a reference to the elongated<br />

anther appendages)

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

The Ethnobotany 489<br />

Pentalinon luteum. a. Flowering branch. b. Node. c. Flower<br />

tube, longitudinally dissected. d. Floral diagram. e. Fruits.<br />

f. Seed with coma. g. Seed. Drawn by Priscilla Fawcett. From<br />

Correll and Correll 1982.<br />

Pentalinon luteum (yellow) ( /Urechites lutea)<br />

[bejuco] ahoga vaca (cow strangler [vine], Dominican<br />

Republic)<br />

barbeiro amarillo (yellow beard, Puerto Rico)<br />

bejuco marrullero (false? climber, Cuba)<br />

Catesby’s vine (Bahamas)<br />

clavelitos (little carnation, Cuba)<br />

corne cabrits (goat horn, Haiti)<br />

curamagüey (Taino?, Hispaniola)<br />

Dominican viper tail (Dominican Republic); hammock<br />

viper’s tail [viperstail] (Florida)<br />

Jamaica nightshade (Jamaica); yellow nightshade<br />

(Jamaica?); nightshade (Cayman Islands)<br />

wild allamanda (Florida)<br />

wild unction (unction /ointment, Bahamas)<br />

Linnaeus ([1753] 1957) called these climbers Vinca<br />

lutea. Then, for many decades, they were called<br />

Urechites lutea, a genus established in 1860 by the<br />

Swiss botanist Johannes Müller of Aargau. However,<br />

Bruce Hansen realized that Pentalinon, described from<br />

plants grown in the Calcutta Botanical Garden in<br />

1845, was an earlier and valid generic name (Hansen<br />

and Wunderlin 1986). Pentalinon now contains two<br />

species, both native to Florida, Central America, and<br />

the Caribbean.<br />

In the Dominican Republic Pentalinon is used to<br />

treat heart disease (cardiotonic), edema, fever, and<br />

colic, and as a purgative (Hocking 1997). Plants are<br />

used to treat headache in Guatemala (Rosatti 1989).<br />

However, doing so is dangerous because the latex is<br />

poisonous, having been used to poison arrows in<br />

tropical countries (Rosatti 1989). It is poisonous to<br />

cattle; people powder the leaves to kill destructive<br />

insects and animals (ants, dogs) (Liogier 1974).<br />

Among the poisonous compounds are the cardenolides<br />

oleandrin, urechitin, and urechitoxin (Gibbs<br />

1974).<br />

Penthorum<br />

(From Greek pente, five, and horos, a column or pillar,<br />

referring to the five-parted flowers)<br />

Penthorum sedoides. a. Top of plant. b. Part of procumbent<br />

stem of plant with roots. c. Cluster of flowers and fruits.<br />

Drawn by Vivian Frazier. From Correll and Correll 1972.<br />

Penthorum sedoides (like Sedum)<br />

[ditch, Virginia] stonecrop (from Old English<br />

stáncrop, combining ‘‘stone,’’ a rock, and

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

490 Florida Ethnobotany<br />

‘‘crop,’’ as gathered from the top of an herb for<br />

culinary or medical purposes; combined, the<br />

designator has been in use since about A.D.<br />

1000, first as the common name for European<br />

Sedum acre; modifiers were added later for other<br />

plants)<br />

Penthorum has been an oddity since it was<br />

discovered. Jan Gronovius first included it in his Flora<br />

Virginica of 1739 /1743. Linnaeus described it in 1744,<br />

and in Species Plantarum ([1753] 1957) said only of it<br />

that it had a ‘‘Habitat in Virginia.’’<br />

Depending on how it is interpreted, the single<br />

American species either belongs in the Saxifragaceae<br />

along with one to three others that grow in Asia, or in<br />

its own isolated family, the Penthoraceae (Cronquist<br />

1981, Mabberley 1997). In some regards, the plants are<br />

transitional between the Saxifragaceae and Crassulaceae<br />

(Cronquist 1981).<br />

Penthorum sedoides grows from New Brunswick,<br />

southwestern Quebec, southern Ontario, Michigan,<br />

Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Nebraska south to Florida<br />

and Texas. Within that large range, only two tribes<br />

have been recorded as using the plants.<br />

In her 1975 master’s thesis at the <strong>University</strong> of<br />

Tennessee, Knoxville, Myra Jean Perry recorded that<br />

the Cherokee used the leaves as a potherb (Moerman<br />

1998). That is an odd use, indeed, because few to none<br />

of the other members of the family are considered<br />

edible. In Iowa, the Meskwaki made a cough syrup of<br />

the seeds (King 1984).<br />

Although the plants are not mentioned by Porcher<br />

(1863), they are discussed by Millspaugh (1892). He<br />

wrote, ‘‘It has always held a place in domestic practice<br />

as an astringent in diarrhoea and dysentery.’’ According<br />

to him, two physicians brought the plants to notice<br />

in 1875 as a remedy for irritation of the mucous<br />

membranes and to treat maladies like pharyngitis,<br />

vaginitis, and tonsillitis. In 1931, Maud Grieve’s book<br />

A Modern <strong>Herba</strong>l included the report that ‘‘this plant<br />

has of late attracted much notice ... as a remedy for<br />

catarrh, catarrhal inflammation of the larynx, chronic<br />

bronchitis ... and affections of the stomach and<br />

bowels. It has also been employed with success in<br />

treatment of diarrhoea, haemorrhoids and infantile<br />

cholera’’ (Coffey 1993). Foster and Duke (1990) echo<br />

the same information, but the species is not mentioned<br />

by Bremness (1994), Bown (1995), or Duke et al.<br />

(2002).<br />

Peperomia<br />

(Ruíz and Pavón combined Greek peperi, pepper, and<br />

homoimos, resembling)<br />

Peperomia obtusifolia (leaves blunt or round at<br />

apex)<br />

agronemia (of cultivated places?, Hispaniola)<br />

climbing pepper (Belize); wild pepper (Florida,<br />

Bahamas)<br />

cupeycito (little cupey, Clusia rosea; Hispanized<br />

Taino, Dominican Republic)<br />

lentejuela (applied to Lepidium virginicum in<br />

Morton 1981)<br />

pàrahá (Paya, Honduras)<br />

peperomia (Florida)<br />

tep-pim (tep, something adorned, pim, fat or large,<br />

Maya, Belize)<br />

The genus Piper was the only one that Linnaeus<br />

([1753] 1957) recognized, and he included 17 species.<br />

He called these plants Piper obtusifolium, and noted<br />

that they had been discussed previously by Charles<br />

Plumier in 1693 as Saururus repens, folio orbiculari<br />

nummulariae facie (prostrate lizard’s tail, with<br />

rounded leaves resembling coins). Then, after their<br />

exploration of Peru, Hipólito Ruiz López (1754 /1815)<br />

and José Antonio Pavón (1754 /1844) created the<br />

genus Peperonia in 1794 in their book Flora Peruvianae,<br />

et Chilensis Prodromus (Preliminary Flora of<br />

Peru and Chile). The genus now contains 1000 tropical<br />

species, mostly in Americas (Mabberley 1997).<br />

Several of the Peperomia are widely used as<br />

medicines. Peperomia pellucida is the most famous<br />

(Liogier 1974, Ayensu 1981, Morton 1981), but P.<br />

magnifoliifolia is more similar morphologically to P.<br />

obtusifolia; it has even been recorded in botanical<br />

literature under the latter name. Peperomia magnifoliifolia<br />

is used in Barbados as a remedy for coughs and<br />

colds (Morton 1981). In Veracruz, the Zoque-Popoluca<br />

treat erysipelas with it (Vásquez and Jácome<br />

1997).<br />

Persea: Red Bay<br />

(A classical name doubtfully from Persica; from<br />

Persian, or from Greek persis)<br />

Americans and Bahamians call Persea borbonia<br />

the red bay. They have used that name since at least<br />

the time of Mark Catesby (1731). Calling trees ‘‘bays’’<br />

is obvious because they belong to the same family of<br />

plants (Lauraceae) called by that name since the time<br />

of the Greeks and Romans. ‘‘Bay’’ is derived from<br />

Latin baca.<br />

Until recently, it never occurred to me to ask why<br />

the plants were called ‘‘red’’ bays. When a colleague<br />

asked me why, I found that ‘‘red’’ in the name refers to<br />

the wood. Of the trees that he saw in Virginia and

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

The Ethnobotany 491<br />

Persea borbonia. a. Branch with flowers. b. Bud. c. Flower.<br />

d. Anther. e. Branch with fruit. Drawn by Vivian Frazier.<br />

From Correll and Correll 1972.<br />

Carolina, Catesby said, ‘‘The wood is fine-grain’ed,<br />

and of excellent use for Cabinets, etc. I have seen some<br />

of the best of this Wood selected, that has resembled<br />

Water’d Sattin, and has exceeded in Beauty any other<br />

Kind of Wood I ever saw.’’ Sargent (1905) wrote that<br />

the wood was ‘‘heavy, hard, very strong, rather brittle,<br />

close-grained, bright red.’’ The wood has been used<br />

from at least the time of Catesby for cabinets, and also<br />

on the interior finish of houses. Formerly, it was used<br />

in ship- and boatbuilding. Comparing its wood to<br />

mahogany with ‘‘Florida mahogany’’ is high praise<br />

indeed.<br />

Williams ([1837] 1962) also praised the wood. He<br />

wrote, ‘‘This tree produces timber inferior only to<br />

mahogany, which it closely resembles.’’ He then added,<br />

‘‘The young leaves are often used for tea, which is a<br />

most pleasant and healthful beverage.’’<br />

The Flemish Charles de l’Ecluse, who became the<br />

king’s botanist to James I of England, was the first to<br />

apply the name Persea to these plants. Philip Miller<br />

picked up the name and continued its use. That Greek<br />

name originally was used by Theophrastus and<br />

Hippocrates for an unknown Egyptian tree. Of that<br />

tree, Pliny wrote, ‘‘Persea ... is far different from the<br />

Peach-tree Persica and beareth fruit like vnto Sebes-<br />

ten, of colour red’’ (from a 1602 translation). The<br />

derivation of Persea was thought by Pliny to be the<br />

same as Persica (from Persia), but that is dubious.<br />

Apparently, Persia is derived from Greek persis, which<br />

in turn was probably taken from Arabic fars. Some<br />

have speculated that the Old World plants called<br />

Persea were Cordia myxa (Boraginaceae), but their<br />

identity remains uncertain.<br />

Curiously, Linnaeus did not follow either l’Ecluse<br />

(alias Clusius) from 1601 or Gaspar Bauhin from 1623<br />

in keeping these plants distinct from Laurus. Instead,<br />

Linnaeus called the plants Laurus persea, which we<br />

now know as P. americana (avocado). Linnaeus’s<br />

reluctance to keep Laurus separate from Persea is<br />

reflected today in the chaotic status of genera in the<br />

family.<br />

Other names for red bay and its variations<br />

(including P. pubescens) are laurel-tree, shore bay,<br />

swamp bay, swamp red-bay, sweet-bay, and tiss-wood.<br />

The last name, ‘‘tiss-wood,’’ may be related to its use<br />

in tisanes for a beverage or medicine. The first record<br />

of it that I saw was by Vignoles ([1823] 1977) who<br />

spelled it ‘‘tiswood.’’ Almost certainly, this plant and<br />

sassafras (Sassafras albidum) have been used interchangeably<br />

since Europeans encountered people using<br />

them. Leaves of both have served as the basis of<br />

gumbos (from Choctaw, kumbo), especially those<br />

including crabmeat.<br />

The Miccosukee call these trees tó:lî, their relatives<br />

the Creeks say tó:la, and the Koasati say tolá.<br />

Surprisingly, because they were supposed to have a<br />

distinct language, the Timucua also said tola. Those<br />

are simple terms that cannot be translated. However,<br />

the Alabama call the tree ittoissi kosáoma (itto, tree,<br />

hissi, hair, kosooma, stinking). This may be what the<br />

Choctaw called iti chinisa (striped tree).<br />

William Bartram ([1791] 1958) recorded that the<br />

trees were called eto mico [itto micco, eto micco] (eto,<br />

tree, mekko, tree, Creek). Simmons ([1822] 1973) noted<br />

that the Seminoles were still using the name. This tree<br />

is perhaps the most important plant among modern<br />

and historic Seminoles. The Seminoles used the leaves<br />

to make a beverage like tea. They also used the dried<br />

leaves in cooking like their relatives the Choctaw, and<br />

they made spoons from the wood. They were not the<br />

first to use the plants in Florida, as the pollen of P.<br />

borbonia has been found in a pre-Columbian site near<br />

Lake Okeechobee (Hogan 1978).<br />

Red bay has been used by the Seminoles as an<br />

abortifacient, analgesic, antiemetic, diuretic, aphrodisiac,<br />

emetic, febrifuge, a laxative, a love medicine, a<br />

panacea, a psychological aid, in childbirth, to cure<br />

dreams, and to improve the appetite, as well as in a<br />

ceremonial context (Sturtevant 1955). The Creeks and<br />

their relatives the Seminoles diagnose diseases in ways

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

492 Florida Ethnobotany<br />

different from Europeans and Americans. Each series<br />

of symptoms is identified with a name as in our<br />

system, but their nomenclature involves an animistic<br />

worldview. Among the diseases they recognize, Persea<br />

has been used to treat ‘‘Bear Sickness’’ (fever, headache,<br />

thirst, constipation, and blocked urination),<br />

‘‘Bird Sickness’’ (diarrhea, vomiting, appetite loss),<br />

‘‘Buzzard Sickness’’ (vomiting in children), ‘‘Cat<br />

Sickness’’ (nausea), ‘‘Dead People’s Sickness’’ (grief,<br />

cough, appetite loss, vomiting; sometimes the same as<br />

‘‘Ghost Sickness’’), ‘‘Deer Sickness’’ (numb, painful<br />

limbs and joints), ‘‘Fire Sickness’’ (fever and body<br />

aches), ‘‘Ghost Sickness’’ (grief, cough, appetite loss,<br />

vomiting, dizziness, staggering, sometimes the same as<br />

‘‘Dead People’s Sickness’’), ‘‘Hog Sickness’’ (unconsciousness),<br />

‘‘Mist Sickness’’ (eye disease, fever, chills),<br />

‘‘Opossum Sickness’’ (appetite loss and drooling in<br />

babies), ‘‘Otter Sickness’’ (diarrhea and vomiting),<br />

‘‘Raccoon Sickness’’ (diarrhea in babies), ‘‘Rainbow<br />

Sickness’’ (fever, stiff neck, backache), ‘‘Scalping<br />

Sickness’’ (severe headache, backache, low fever),<br />

‘‘Sun Sickness’’ (eye disease, headache, high fever,<br />

diarrhea), ‘‘Thunder Sickness’’ (fever, dizziness, headache,<br />

diarrhea), ‘‘Turkey Sickness’’ (dizziness or ‘‘craziness’’),<br />

and ‘‘Wolf Sickness’’ (vomiting, stomach<br />

pain, diarrhea).<br />

Additionally, red bay has been used to treat<br />

sickness caused by adultery, including headache,<br />

body pains, and ‘‘crossed fingers.’’ As an aphrodisiac,<br />

the leaves are sung over to attain the love of a<br />

particular girl. If the aphrodisiac has worked, the<br />

leaves may be rubbed on the mother’s body during<br />

protracted labor.<br />

Sometimes red bay is even considered a panacea<br />

where the leaves are used for everything and can be<br />

added to any medicine. As a psychological aid, the<br />

leaves are used to cure fear in babies caused by dreams<br />

about raccoons or opossums. In addition, an infusion<br />

of leaves may be used to steam and bathe the body of<br />

an ‘‘insane’’ person. The plant may be burned to work<br />

the same cure.<br />

There are also particular ceremonial applications.<br />

A decoction is taken as an emetic by doctors to<br />

strengthen their medicine. That may be the use at any<br />

time, or particularly when a death has occurred. The<br />

leaves are used as emetics during funeral ceremonies,<br />

carried by every member of the burial party, placed on<br />

top of casket, and burned to keep the soul of the<br />

recently departed from returning home. Leaves are<br />

also added to food after a recent death.<br />

Some recognize a wetland form as a distinct<br />

species, calling it P. palustris. The Creeks have used<br />

the root of that form as a ‘‘hydrogogue’’ and alterant.<br />

The decoction is considered diaphoretic in ‘‘fevers of<br />

all descriptions’’ by the Choctaws (Bushnell 1909).<br />

Persea is notorious for having poisonous compounds<br />

although it provides food and medicine for<br />

humans and other animals. The red bay and its<br />

variations contain an array of essential oils, including<br />

camphor, cineol, eucalyptol, and p-cymene (Tucker et<br />

al. 1997). Those, and probably other chemicals yet to<br />

be identified, are responsible for the tight evolutionary<br />

relationship between the spicebush swallowtail butterflies<br />

and members of the Lauraceae. The spicebush<br />

swallowtail (Papilio troilus) and the Palamedes swallowtail<br />

(P. palamedes) are among the few insects that<br />

can detoxify or sequester the poisons, and they<br />

specialize on Persea (cf. Lederhouse et al. 1992, Carter<br />

and Feeny 1999).<br />

There are perhaps 200 tropical Asian and American<br />

species in Persea (Mabberley 1997). Many of<br />

them are part of local pharmacopoeias, but none is as<br />

famous as the avocado. Although most people know<br />

that species as the primary ingredient passed down<br />

from the Aztecs almost without change in the recipe<br />

for guacamole (Coe 1994), few realize that it is also<br />

medicinal. The leaves and other parts contain a variety<br />

of toxic compounds that are dangerous to vertebrates<br />

if consumed in quantity (Hargis et al. 1989, Grant et<br />

al. 1991, McKenzie and Brown 1991, Stadler et al.<br />

1991, Burger et al. 1994, Oelrichs et al. 1995). In spite<br />

of the toxic chemicals in the leaves, Latin Americans<br />

regularly use them in small quantities as a spice. They<br />

give foods an anise flavor (Hearon 1993). Those same<br />

compounds show potential as insecticides (Oberlies et<br />

al. 1998) and give some protection against Giardia<br />

(Ponce-Macotela et al. 1994).<br />

Avocado and other species in the genus show<br />

considerable dietary and medicinal potential (Zanobi<br />

et al. 1974, Meade et al. 1980, Mohan and Kekwick<br />

1980, De-Oliveira et al. 1985, Ballot et al. 1987, Ma et<br />

al. 1989, Sheldon et al. 1990, Guevara et al. 1994,<br />

Eccleston and Harwood 1995, Kimura et al. 1995,<br />

Koua et al. 1998, Castro et al. 1999, Chiapella et al.<br />

2000, Domergue et al. 2000, Kim et al. 2000,<br />

Kruthiventi and Krishnaswamy 2000, Caballero-<br />

George et al. 2001, Hashimura et al. 2001, Kawagishi<br />

et al. 2001, Kut-Lasserre et al. 2001, Schlemper et al.<br />

2001, Stucker et al. 2001, Lequesne et al. 2002).<br />

Therefore, their congener P. borbonia is showing the<br />

same patterns as its relatives. In spite of its extreme<br />

importance among indigenous people in the southeastern<br />

United States, red bay has never appeared in<br />

the journal Economic Botany (Kaplan 2001).<br />

Although modern southern culture owes as much<br />

to the Creeks as any group of people, their botanical<br />

heritage has been slighted (Hudson 1976). The Creeks<br />

and their relatives the Seminoles were aware of all the<br />

bays. Bartram ([1791] 1958) told us Creeks called P.<br />

borbonia the eto miko, and Magnolia grandiflora was

© 2004 by CRC Press<br />

The Ethnobotany 493<br />

tolochlucco (big bay). By the 1950s, the Seminoles had<br />

shortened those names to to:li and to:lhátkí (white<br />

bay, M. virginica). What will be remembered in the<br />

next 200 years?<br />

Phalaris<br />

(Greek phalaris, phaleris, used by Dioscorides, fl. A.D.<br />

40 /80, for some kind of grass; presumably from<br />

phalaros, having a patch of white or crest, alluding to<br />

the inflorescence)<br />

alpiste (French)<br />

canaria (Italian); canary-grass (‘‘canary,’’ referring<br />