The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch is a wonder of art. By that I don’t just mean it is one of the world’s greatest paintings. It is also something we wonder at, astonished, like a rare relic in a cabinet of bizarre curiosities. What is happening in this outrageous display of unfettered imagination and what can it possibly mean?

Last year, the 500th anniversary of the death of Bosch was marked by a thrilling exhibition of his paintings and drawings in his home town Den Bosch, in the southern Netherlands. Yet one masterpiece was missing. The Garden of Earthly Delights does not travel from Madrid, where it hangs in the Prado museum. A book of the Prado’s own Bosch quincentenary published this month by Thames and Hudson makes up for that absence. It explores the latest discoveries and theories about Bosch’s most stupendous work with accurate colour images of many of its hypnotic details and infrared images of the three wooden panels that make up this religious – or pseudo-religious – painting.

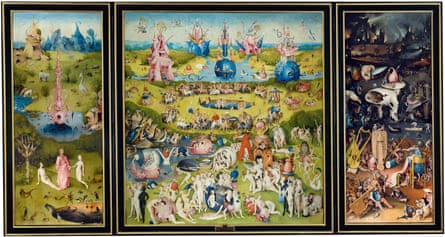

The Garden of Earthly Delights is a triptych that can be folded open. When closed, it shows a monochrome painting of the creation of the world, with God looking down on a flat landscape sealed inside a giant bubble. Open the tall side panels on their hinges and you are confronted by a world – or rather three worlds – of lurid colour and hallucinatory invention. In the left panel, God introduces Eve to Adam in the Garden of Eden. In the one on the right, Bosch imagines all the sufferings and monstrosities of hell, including a bird-headed creature eating a naked man, a pig dressed as a nun and a hollowed out giant with trees for limbs and an inn inside his pale egg-like torso.

The most hypnotic and perplexing scene, however, is the huge central panel, which depicts a dreamlike landscape of carnal bliss where people cavort naked, consume giant strawberries, explore pink flesh palaces and ride barebacked on fantastic creatures. What on earth is going on?

The Garden of Earthly Delights is popular because we can see surreal images of our own, modern existence in it. Since the 1960s, it has been hailed as a psychedelic romp. Those giant strawberries are like free narcotics at a music festival. What strikes us when we look at it is the sheer joyous excess and mad profusion of this painter’s mind. Was he some kind of heretic, speculating on an alternative lifestyle of free love and fruity fun with no thought of tomorrow?

No such luck, say the authors of the Thames & Hudson book Bosch. They see this mysterious painter as a grimly conservative medieval Christian for whom earthly life is a spectacle of folly and sin with only one destination for those who succumb to its temptations: the horror show that is hell. The seductions of gargantuan fruit and nudity are false, argues this volume of state-of-the-art scholarship, for Bosch is an artist warning of the punishments awaiting all who indulge themselves. This is a long way from 20th-century interpretations that tried to connect him with heretical movements and subversive ideas.

The chances of The Garden of Earthly Delights being a heretical vision of freedom have got a lot smaller in the light of the discovery in the 1960s that it was painted for the princely House of Nassau. This is not a secret attack on orthodox religion but a work that pleased the establishment. In the 16th century, it was seized by the Spanish monarchy and taken to Madrid, where it was revered as a gloomy picture of the consequences of sin. And yet …

One fact made very clear by this book offers another way to consider The Garden of Earthly Delights. It is a very simple fact: the painting’s date. The latest evidence, from scientific dating of the wooden panels to visual connections with other works of art, establishes that it was created between about 1490 and 1505.

That puts it at the heart of the Renaissance, when new ideas were changing Europe. Was Bosch totally immune to those ideas? Was he completely unaware of the printing press, the discovery of the Americas and the swirl of new knowledge and curiosity sweeping Europe?

Knowing this, look again at The Garden of Earthly Delights. It is painted as three superbly convincing perspective landscapes, not unlike Leonardo da Vinci’s contemporary works. Another Leonardo-like touch is the spiralling host of birds rising from a rocky mountain in Paradise. Just like Da Vinci, Bosch has watched birds carefully. He is curious about nature. This curiosity fills his precise, detailed painting. Architecture that seems to be modelled on human organs suggests interests in anatomy, exotic worlds, even science fiction; the giant fruits suggest legends of opulent places far away. Most of all, if this was painted in the later 1490s or early 1500s, the ecstatic nudes may be inspired by images of “naked peoples” brought back by early travellers to the Americas.

There is a curiosity, a freedom of thought, an appetite for discovery in this painting that still makes us see ourselves in it. Bosch painted the modern world before it existed. This Renaissance visionary imagines boundless New Worlds. His masterpiece is a prophecy of us.