After nearly two decades as a songwriter and musician, James Blunt finally understands who he is. His earlier work, including his 2004 breakout debut album, Back to Bedlam, pondered some of life’s big questions, but today Blunt has new ones. On his seventh album, Who We Used to Be, out now, the musician looks back in order to move forward. He reflects on everything from refusing to settle down to grappling with deep loss. The record also includes a sparse, pensive song about the death of Carrie Fisher, whom Blunt lived with while recording Back to Bedlam.

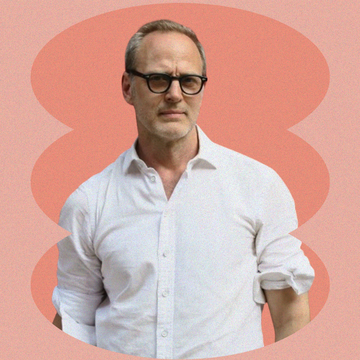

Along with the album, Blunt penned his memoir, Loosely Based on a Made-Up Story: A Non-Memoir, which similarly examines what has brought him to where he is now. The book (which has yet to receive a U.S. release) follows the English musician through his youth into adulthood as he transitioned from the British army to a life in music. It’s clear that Blunt has reached a transitional moment when he has to reconcile with the past in order to understand where it leads. Blunt spoke with Shondaland from his home in the English countryside, where he lives with his wife and kids, about Who We Used to Be, writing about Fisher, and his online persona.

EMILY ZEMLER: You haven’t released new music since 2019. How long did you spend thinking about this album?

JAMES BLUNT: I actually don’t think very much! If I have stuff to write about, the songs come easily. I only ruminate if I’m struggling in some way. For instance, “Dark Thought” is a song for Carrie Fisher on this album. And the song came very quickly, but I wanted to write a song for many years, and I [hadn’t] found the words. Sometimes you just think so hard, and you try so hard, and it never comes that easy because you’re overthinking it. But then the moment came, and I realized what I needed to think about — about the journey when I went back to our house, put my hand on the gate, and broke down in tears. At that moment, I found the words I needed to say.

But the other songs on the album have come really quickly. I started it in September last year, [and] it takes me six months to write a record. I’m going through this amazing shift in my life from the young man who left the army and had a ton of questions about who I was going to meet, what I was going to be, what I was going to do. And some of those questions have been answered. I’m married. I have a family. I’ve been a musician for a period of time now. At the same time, my parents are getting older; my place in the world is changing. So, I have some new questions in the world. That’s why the album’s called Who We Used to Be. Because of those big changes in my life, there’s been lots to write about.

EZ: What’s the most pressing question you have now?

JB: Well, I suppose, how does it all end? Last year, my label put out my greatest hits. Psychologically, you think to yourself, “greatest hits” means that you’re at the end. You imagine your greatest hits collection having all your best songs on it, and surely when you do so, it must be the end. And then my record deal with Atlantic was over. The pandemic had stopped us from touring. But then we came out of the pandemic, and I signed a new deal with Atlantic, and I’m still writing songs. So, these [new] songs obviously aren’t going on my greatest hits album. So, as far as I understand, these are all bonus tracks. These are all really fun. So, I’ve been given this new lease of life. And where does it all end? I don’t know because it feels like it’s just beginning. There’s some new chapter.

EZ: When that’s the big question, do you think the album is still optimistic?

JB: Definitely. I mean, it’s nostalgic. There’s a look back into the past, but it’s nostalgia with hope. I have a friend who just reached my age, 49, and just seems to not have the hunger for life anymore. This is me saying, “I won’t die with you. Where’s the fire inside?” People have asked me, “When are you going to settle down?” And I’m not settling down. [My wife] moves at a faster speed than me; [that’s] who I need to catch up with. There’s no notion of settling down. It’s instead about speeding up and meeting someone who works at the same speed as you.

EZ: The idea that you have to “settle down” is something of a fallacy anyway.

JB: Exactly that. And it goes into the fear I had as a young teenager, which is that we always ask the same questions of each other: What are you going to be? What are you going to do? When are you going to get married? When are you going to have children? When are you going to have another child? We ask these questions to reassure each other that we’re all following this similar path. It gave me the fear as a young man that I don’t want to just follow this path. I didn’t want to be in the army forever. I didn’t want to be just another cog. I wanted to go into the music business, to live a different life. I wanted to live in Ibiza.

EZ: When you’re writing a song, are you ever surprised by what comes out of you?

JB: Yeah. I think sometimes after the song, maybe three months later, you go, “Wow, that really does sum up a feeling really well. I really nailed how I felt.” Explaining how we feel, even in this interview, is hard. Feelings are tricky. It takes a while to perfect how to express yourself. Again, the song for Carrie — I just love it. It’s so magical but so simple. It just describes what I did: “Get over the hills to say goodbye/But all I found was a ‘For Sale’ sign/Put my hand on the gate, and there’s tears in my eyes/And all there’s been left since the minute you died are the chandeliers and the trees surrounded in bees/And now they’re just covered in leaves.” It’s so obvious, but it’s the journey I took. The simplicity is what makes it special and honest. And that harks back to “You’re Beautiful.” Simple and honest.

EZ: It seems simple to you because you lived it, but to a listener, hearing your journey of saying goodbye to Carrie Fisher is pretty extraordinary.

JB: Absolutely. So for you, it’s hopefully painting a picture in a way. And the chorus is more clear: “I wish that you would have called somebody/And if I wasn’t there, I’m sorry/You made me believe you were strong/I wish you’d called me and told me that something was wrong.” It just gives you emotion that other people will, hopefully, relate to. Because we all have a person like that.

EZ: When you look back, has the music industry changed a lot since you made your debut album?

JB: It’s changed in so many ways. Some of those things are really positive. Once upon a time, you had to go and find a record store, and now I hear something on the radio, I Shazam it, and I can download it or stream it. That’s incredibly quick. But then again, the investment in music is less. The investment in time is less. We don’t hear albums as much, and I do write albums. I write and record albums. As a result, I suppose, the trickiness is that I don’t write songs for radio, and so my best songs aren’t the ones that are chosen as singles. We have a really weird thing within the record label where they say, “God, James, we love songs No. 1, No. 5, and No. 8. We love them, they’re brilliant, but we’re using No. 2 and No. 3 as singles. We love the other ones, they changed our lives, we cry when we listen to those. But they’re not singles.”

There’s a song on the album called “The Girl That Never Was,” and they said it can’t be a single. It’s not radio friendly. But they told me, “We played that song, and two people started crying and had to leave the room.” I kept pushing and saying, “This was the one that really moved people.” So, we played it again, and again someone had to leave the room crying. It’s really emotional. It has this visceral reaction I can see. So finally, they agreed it could be a single. And I know they’re right. I know it’s not going to work. But I would rather have it fail at radio, and we get to make a video of it and call it a single.

EZ: How often do people cry to your songs in front of you?

JB: Well, with particular songs, a lot. Music is about emotion, and I suppose that’s probably what I just do best. For me, misery sells. Other people have different genres, and they do better than me. I don’t do pop singles as well as the Taylor Swifts of the world. She nails those. Harry Styles, he’s just got some awesome pop singles. Harry Styles has some fantastic, beautiful songs, which as a songwriter, I envy and congratulate him on. A little bit of misery? Yeah, that’s my bread and butter. On the last album, I did “Monsters” for my father, and I think that it captures that sentiment really well.

EZ: Your music is really emotional, but your approach to social media is more sarcastic and dry. Do you think you’ve figured out that balance?

JB: The main thing is: Don’t take it too seriously. If you get involved in the heat of the moment and say something defensive, you’re going to just look as petty as the person writing whatever they’re writing. I’m putting out music, and I’m touring the world, so it would be mad to be upset by these things. I’m playing to thousands of people, and then I open my phone, and one person hates my music. Humans are weird that way where we remember the [negatives] but never the positives. So, you have to learn not to take it seriously and to laugh at [yourself]. You should just laugh at yourself.

EZ: Your memoir doesn’t have a release date in the U.S. yet, but can you talk about what inspired you to write a book at this point in your career?

JB: I’ve been in this business for 20 years now. So, the things I’m writing about are still within the conscious psyche. If I let another 20 years go by, then the people I’m writing about would be all dead. I mean, actually, it should get an American release because lots of what I’ve written about is very relevant to my time in Los Angeles, in Hollywood, living with Carrie. It was a really interesting time.

EZ: Was it fun to go back and recollect through the past 20 years?

JB: It was amazing. Like, what a f--king journey. It was great, great fun, and how nice to be able to land on my feet on the ground and not be f--ked up by the whole thing. It would have been easy to come out of [it] damaged. I just did the audiobook, and it was a really moving experience. I was going, “I can’t believe we did some of those things.” Some amazing things and some terrible things. And then, of course, to relive the losses along the way. We got to the bit about Carrie, and I cried my eyes out although we were recording it. It’s just the sound of some guy crying for three minutes.

EZ: When you look back, what are you most proud of?

JB: As a musician, I played on the main stage at Glastonbury twice. I played the festival three times. Those were moments I never thought I’d experience. Awards, but they don’t really mean that much. They’re like little tokens on the top of it. What am I most proud of? I think the normality. The normality that I’ve still got to have. My parents have forgiven me for when I’ve been a d--k. When I’ve been an idiot, when I’ve let it get to me. They’ve carried me through in many ways. I’ve got my feet on the ground. I’m a normal human being, and that’s an achievement in this business.

Emily Zemler is a freelance writer and journalist based in London. She regularly contributes to the Los Angeles Times, Rolling Stone, PureWow, and TripSavvy, and is the author of two books. Follow her on Twitter @emilyzemler.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY