- Astronomers claim to have come up with a new origin story for Saturn’s largest moon, Titan (1).

- Saturn's planetary system, which has one large moon and many smaller moons, is unique in the solar system.

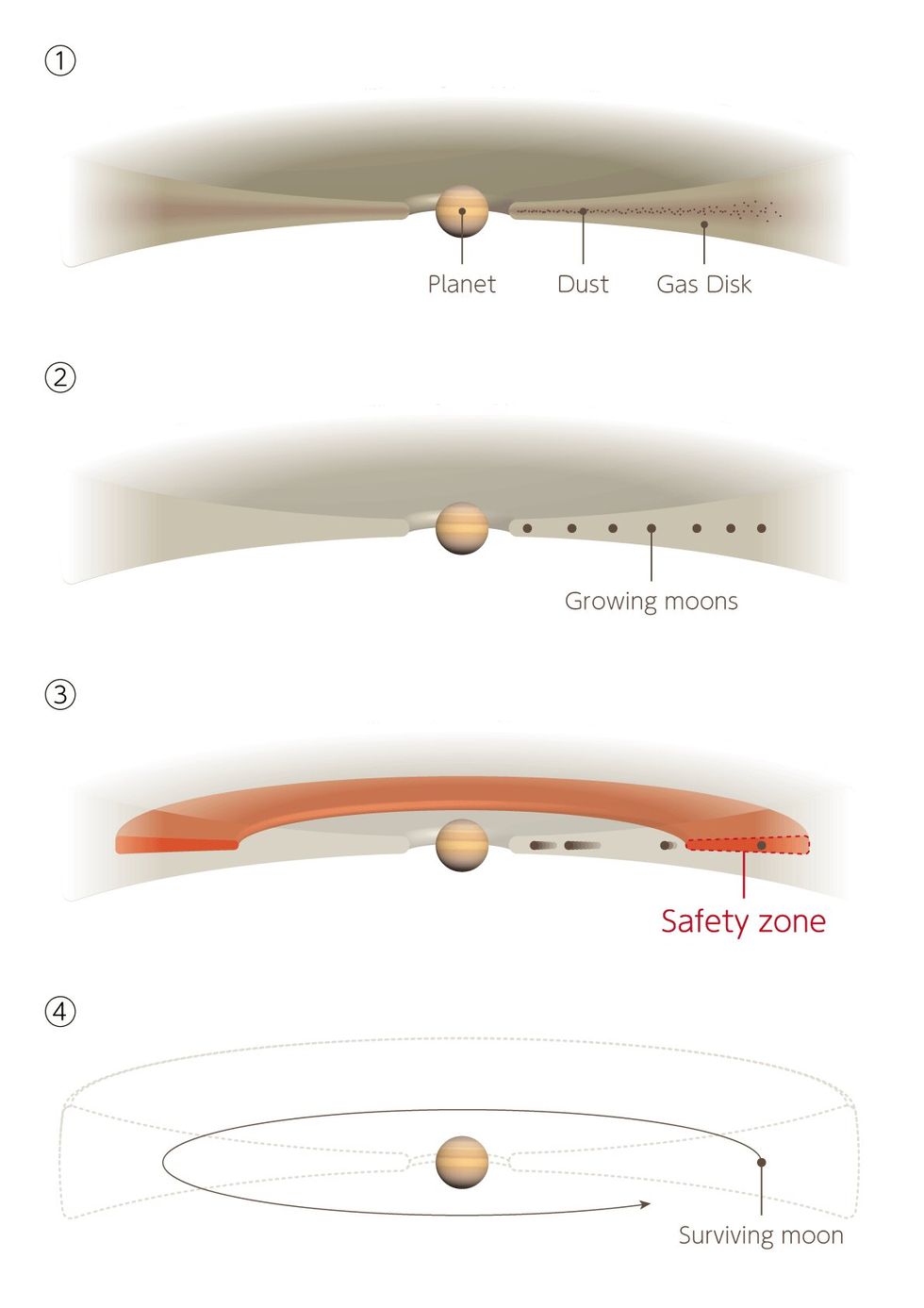

- There may be an orbital "safety zone," according to new models, which keeps larger moons from falling into their parent planet.

The solar system is filled with mysterious moons. Understanding how they formed is no small task.

Some moons, like Triton (4), may have formed elsewhere in the solar system before being scooped up by their planet’s gravitational pull. Many other moons form alongside their parent planet as aggregations of gas, dust, and other materials. Some models have shown that the largest of these moons meet a tragic end and are eventually consumed by their parent planet.

Saturn’s moons are a mysterious bunch. It’s a completely unique system that doesn’t fit neatly into either of these boxes. The planet is surrounded by tens of smaller moons and one large moon, Titan (1), the second largest in the solar system. Astronomers have long tried to unravel the Saturnian moon’s origin.

Now, researchers from Nagoya University in Japan and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan have come up with a theory that explains how Saturn’s lunar system forms, along with others like it. The findings are published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

The researchers created a computer model that used updated information about temperature gradients within circumplanetary discs. The increasingly complex models also included other factors that hadn’t previously been taken into account, such as dust opacity, the gravity of nearby moons, and pressure exerted on moons by the gas around it.

The models suggest there may be a “safety zone” in which larger moons can escape the fate of being swallowed up by their parent planets. In these regions, warmer, high pressure gas pushes a moon outward, away from the planet instead of toward it.

"We demonstrated for the first time that a system with only one large moon around a giant planet can form," astronomer Yuri Fujii of Nagoya University said in a statement. "This is an important milestone to understand the origin of Titan." It’s not a celestial slam dunk, though. Of course, the authors admit, there’s no way of knowing for sure whether Titan formed this way.

The current theory is that Titan may have formed early on in the solar system’s history—within the protosolar nebula, which eventually belched out the sun—and not during Saturn’s formation.

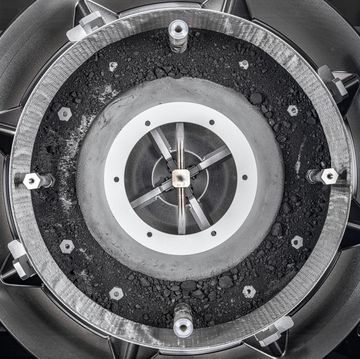

The theory is supported by Cassini’s Huygens probe, which collected data about Titan’s atmosphere on its way down to the moon’s surface. Those observations revealed insight into the atmospheric nitrogen isotopes, which resemble material found in the Oort cloud, a mass of early-formed gas and dust.

Researchers still need to work to understand how Saturn’s strangest moon formed. Luckily, NASA's Dragonfly mission, which plans to explore Titan, will launch for the second largest moon in our solar system in 2026. And the push to observe and identify exoplanets will provide even more information, ultimately helping us understand the planets and moons closer to home.

Jennifer Leman is a science journalist and senior features editor at Popular Mechanics, Runner's World, and Bicycling. A graduate of the Science Communication Program at UC Santa Cruz, her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Scientific American, Science News and Nature. Her favorite stories illuminate Earth's many wonders and hazards.