- Pluto's topography—including its massive heart-shaped feature—may influence its atmosphere more than researchers once thought.

- New research published this week suggests plumes of nitrogen that evaporate from the dwarf planet's surface drive retro-rotational winds in its atmosphere.

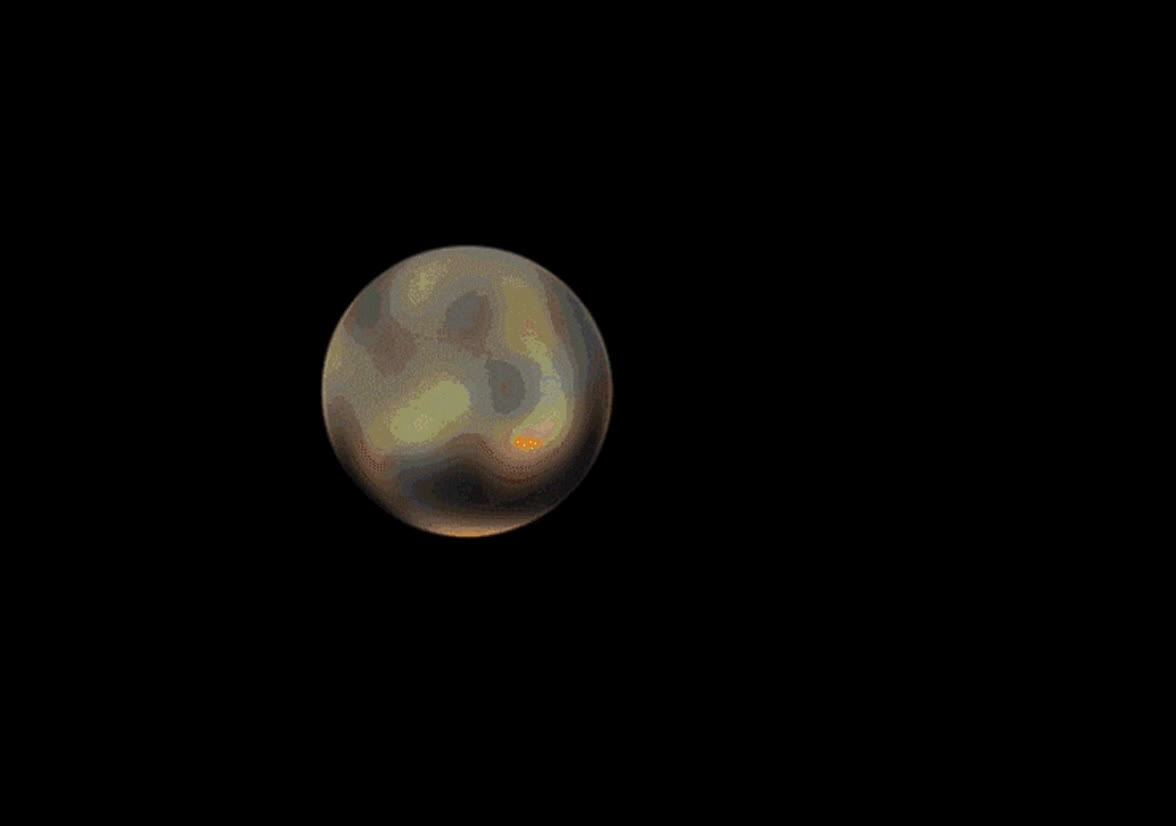

- NASA's New Horizons spacecraft imaged the dwarf planet in 2015, giving researchers their closest look yet.

Thanks to the New Horizons spacecraft’s Pluto fly-by in 2015, we have vivid images of the mysterious dwarf planet at the edge of our solar system. Astronomers have been working around the clock to analyze data collected by the spacecraft, and now, they have new insight into how the small, icy body’s atmosphere works.

Turns out Pluto’s ultra-thin, nitrogen-rich atmosphere is largely powered by a heart-shaped region on the dwarf planet called Tombaugh Regio. This large plateau, which captured the hearts and minds of everyone back on Earth when it was first imaged, is split into two lobes. Sputnik Planitia, the left lobe, has been carved deep by a 620-mile long nitrogen ice sheet. The right lobe is composed of highlands and nitrogen ice glaciers.

“Before New Horizons, everyone thought Pluto was going to be a netball—completely flat, almost no diversity,” astrophysicist and planetary scientist Tanguy Bertrand, of NASA’s Ames Research Center in California, said in a statement. “But it’s completely different. It has a lot of different landscapes and we are trying to understand what’s going on there.”

Recent analysis of the planet’s features is beginning to paint a sharper picture of how the dwarf planet’s atmosphere, which also has traces of carbon monoxide and methane, interacts with its surface. The researchers published a report on the new discovery February 4 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

A thin layer of frozen nitrogen ice covering Tombaugh Regio vaporizes into the atmosphere each day, only to condense each night as the sun sets. This rhythmic pattern sends billowing plumes of nitrogen gas into the atmosphere.

Strangely, this regular influx of nitrogen causes winds high in Pluto’s atmosphere to circulate westward—opposite the dwarf planet’s eastward rotation—in a movement called retro-rotation. Strong gusts that blow along the western face of Sputnik Planitia mirror wind patterns seen on Earth.

These sweeping winds have ultimately shaped Pluto’s surface into the varied landscape we see today and could serve to warm the chilly body. The gusts can also kick up ice crystals, and researchers believe they may be responsible for the dark streaks that mark the heart-shaped feature. “This highlights the fact that Pluto’s atmosphere and winds—even if the density of the atmosphere is very low—can impact the surface,” said Bertrand.

For almost a century, we marveled at Pluto from afar. Now, as we continue to unravel its mysteries, thanks to data supplied by the New Horizons mission, it’s starting to look a lot more familiar.

Jennifer Leman is a science journalist and senior features editor at Popular Mechanics, Runner's World, and Bicycling. A graduate of the Science Communication Program at UC Santa Cruz, her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Scientific American, Science News and Nature. Her favorite stories illuminate Earth's many wonders and hazards.