On this day in 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright were ordinary men, not household names.

For seven years, the brothers had been working toward a grand, larger-than-life invention, beginning in 1896 with glider experiments that they conducted while working as mechanics at a bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio. No one seemed to notice what they were doing. No one seemed to care. In fact, according to Pulitzer Prize-winning author David McCullough, many considered the duo to be "crackpots."

Those critics changed their tune once something incredible happened: On December 17, in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Orville Wright piloted the first mechanical airplane some 20 feet above the ground. It only lasted about 12 seconds and spanned about a 120-foot stretch, but it would usher in a whole new world of transportation—one that's so omnipresent in our lives that we can't wait for our flights to end, get through airport security, and know that we won't be stranded in a cabin with a screaming baby for another eight hours.

But 118 years ago, the first flight was truly a marvel. Ditto the three other flights that would follow on that same windy day. That history, and the course of aviation through the decades, is detailed across the pages of Popular Mechanics, which has been around since the year the Wright Flyer took to the air for the first time. Here's some of what we discovered while looking through our archives.

✈︎ December 1911: The Secret Experiments of the Wright Brothers

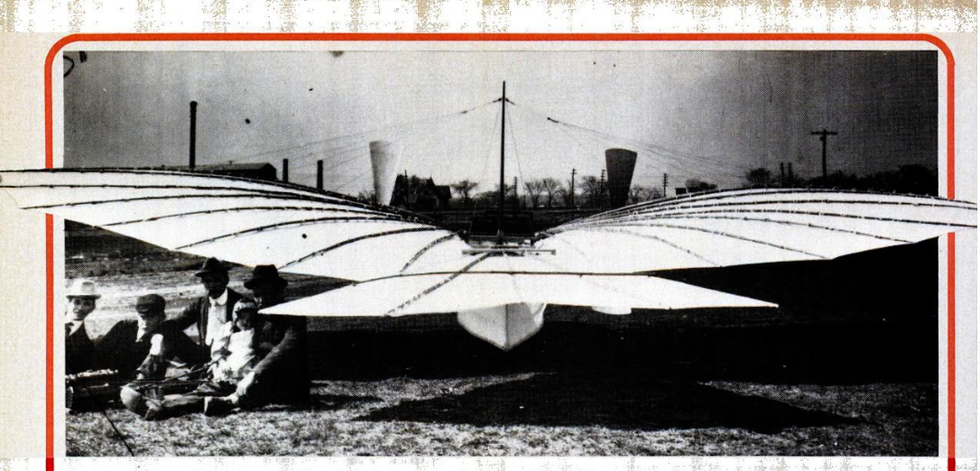

By 1911, rumors had been swirling that the Wright brothers were at it again, secretly building and testing a new glider. So Popular Mechanics sent "an acknowledged authority on aviation" to North Carolina to write "an accurate and complete description of the machine and of results secured, together with an expert analysis of the technical significance of the work," according to a feature in our December 1911 issue.

The story begins with a pretty damning introduction, noting that pretty much all of the speculation around a new Wright machine was pure phooey, propagated by ill-informed reporters:

Despite the wild tales that have been filling the newspapers of late, to the effect that the new Wright machine was really a flapping-wing device, that it was a solution of the problem of flight without power, that it was capable of hovering indefinitely over a selected spot, and that it was capable of imitating the soaring flight of the larger birds, it proves upon first-hand investigation to be only slightly different in appearance and performance from previous Wright gliders and power machines—over which it discloses improvement only in immaterial and minor degree, if at all. Probably the Wrights, themselves, would claim little more for it, though their customary reticence has been in this case, as before, taken as evidence of mysterious and marvelous achievements—by newspaper writers with more interest and enthusiasm than technical competence.

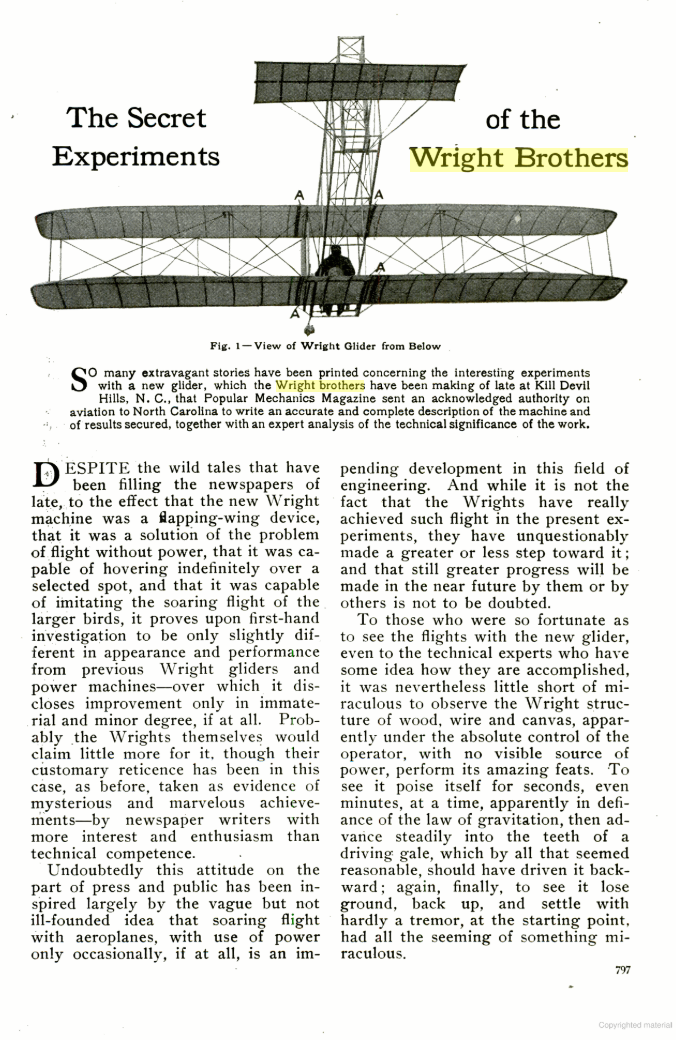

It turned out that the main improvement to the gliders was a Wright-engineered solution to their aircraft's folding wings, which had been warping to help balance the frail plane against harsh wind currents. The brothers had discovered a way to flatten the wings and it worked quite well, but it surely wasn't the stuff of the day's tabloids. The photos included in the magazine illustrated how the balancing act went.

The center section and the two first sections on either side of the plane were "rigidly trussed in all directions" by diagonal bracing wires, leaving the first two sections from each wingtip "free to undergo the distortion involved in the wing warping." This is done through pretty much all the same parts as previous Wright planes, the story noted.

"Thus the wing warping and the double vertical rudder are worked by a lever with a jointed head, placed at the right of the operator, while the elevator is worked by the lever at the left," the story continued.

The piece goes on to describe the pure magic of seeing a Wright glider take flight, despite the fact that no new glamorous plane was to be spoken for during this reporting trip—just a few small improvements that mattered most to the nerds, enthusiasts, and the inventors themselves. The casual observer might not have even noticed the changes.

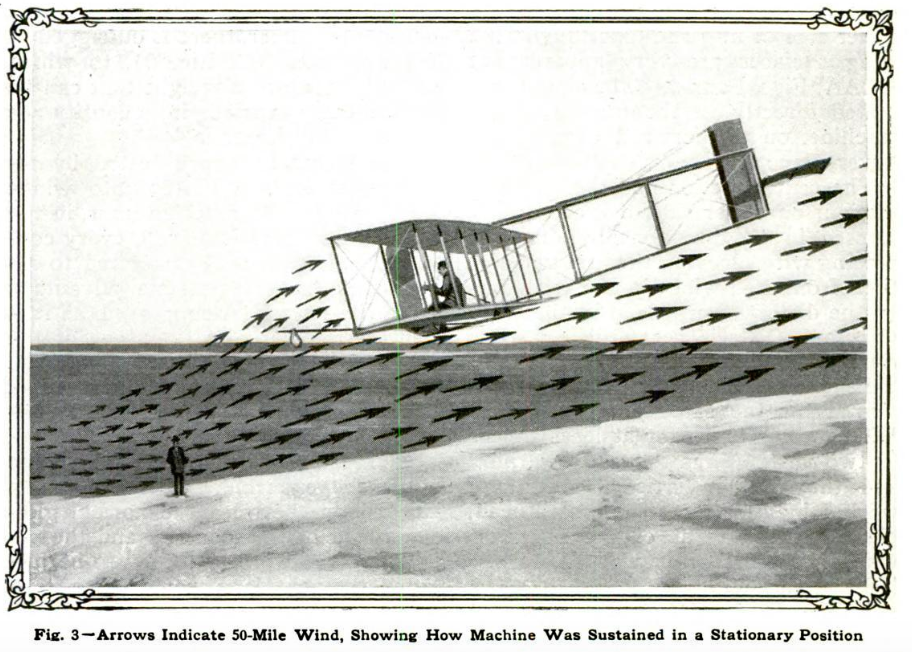

To those who were so fortunate as to see the flights with the new glider, even to the technical experts who have some idea how they are accomplished, it was nevertheless little short of miraculous to observe the Wright structure of wood, wire and canvas, apparently under the absolute control of the operator, with no visible source of power, perform its amazing feats. To see it poise itself for seconds, even minutes, at a time, apparently in defiance of the law of gravitation, then advance steadily into the teeth of a driving gale, which by all that seemed reasonable, should have driven it backward; again, finally, to see it lose ground, back up, and settle with hardly a tremor, at the starting point, had all the seeming of something miraculous.

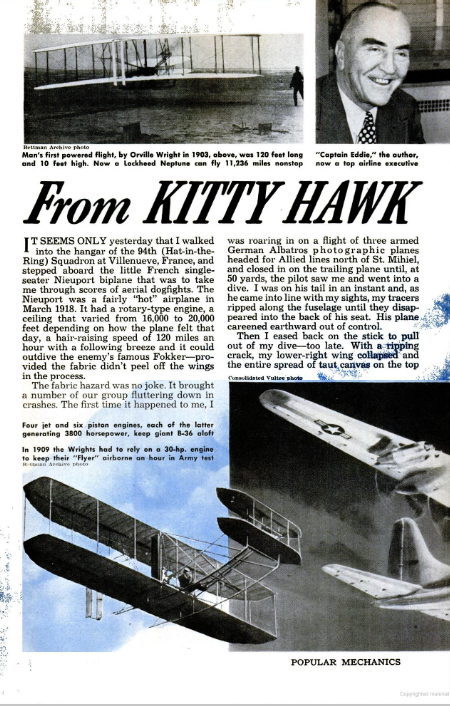

✈︎ January 1952: From Kitty Hawk to Jets

Captain Eddie Rickenbacker—then president and general manager for Eastern Air Lines, Inc., which operated from 1928 to 1991 as one of the largest domestic U.S. air carriers—wrote a guest piece for Popular Mechanics in the early 1950s, detailing his own adventures piloting a French single-seater Nieuport biplane, which was en vogue at the time. In the piece, he recalls:

It seems only yesterday that I walked into the hangar of the 94th (Hat-in-the Ring) Squadron at Villenueve, France, and stepped aboard the little French single seater Nieuport biplane that was to take me through scores of aerial dogfights. The Nieuport was a fairly "hot" airplane in March 1918. It had a rotary-type engine, a ceiling that varied from 16,000 to 20,000 feet depending on how the plane felt that day, a hair-raising speed of 120 miles an hour with a following breeze and it could outdive the enemy's famous Fokker-provided the fabric didn't peel off the wings in the process.

The fabric hazard was no joke. It brought a number of our group fluttering down in crashes. The first time it happened to me, I was roaring in on a flight of three armed German Albatros photographic planes headed for Allied lines north of St. Mihiel, and closed in on the trailing plane until, at 50 yards, the pilot saw me and went into a dive. I was on his tail in an instant and, as he came into line with my sights, my tracers ripped along the fuselage until they disappeared into the back of his seat. His plane careened earthward out of control.

Then I eased back on the stick to pull out of my dive—too late. With a ripping crack, my lower-right wing collapsed and the entire spread of taut canvas on the top wing tore loose and went flapping away in shreds. I fell into a spin and spiraled downward for 10,000 feet. In desperation, at 3000 feet, I gunned the throttle. Amazingly enough, it brought the crippled ship into horizontal position and kept it there until I skimmed over the hangars of our airdrome and onto the dirt runway amid a cloud of dust, noise and debris. How I walked away from that mess without a scratch is a thing no mere man can explain.

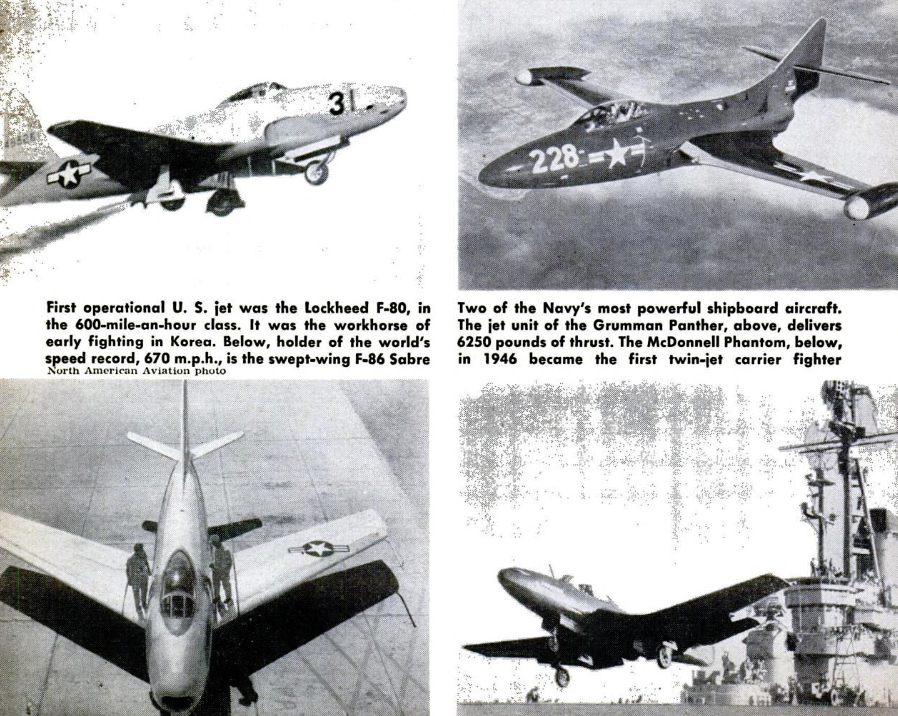

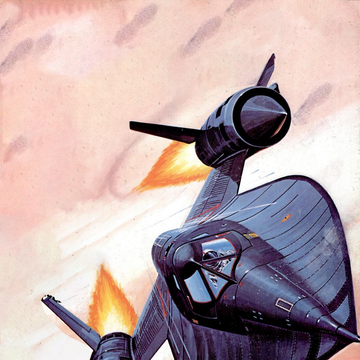

Rickenbacker goes on to ponder how different these planes, and the original gliders designed by the Wright brothers, are from the plane that he described above. And how these transformed into the power-hungry beasts that could "piece the ether at speeds faster than sound" and "climb more than four miles high" by 1952.

Excuse us for a moment as we get a little meta, but Rickenbacker notes that if you took every issue of Popular Mechanics up to that point—beginning in 1903, when the magazine first began publishing, which he points out is incidentally "about the time man started to fly"—3,000 different models of planes had taken to the skies.

Humankind's obsession with flight, though, dates back before the Wright brothers, Rickenbacker wrote. Despite what North Carolina license plates suggest, the Wrights were not the first to fly after all.

Although we date man's ability to propel himself through the air in controlled flight back to the Wright brothers, Americans were interested in, and contributed to, aeronautics for 120 years before that historic event took place at Kill Devil Hills, near Kitty Hawk, N. C. Benjamin Franklin was probably one of our first aviation enthusiasts. His correspondence in 1783 and 1784 indicates not only a keen interest in the mechanics of the gas-filled balloon, but a prophetic understanding of its future application in warfare. Before the United States Constitution was drawn up, Americans were flying.

A 13-year-old boy, Edward Warren, is believed to be the first American to soar above the earth. One June 24, 1784, he volunteered to make a flight in a captive balloon and took off from a site near Baltimore, Md. The balloon was built by a man named Peter Carnes. In November of the same year, Dr. John Jeffries of Boston sailed across the English Channel in a balloon with Pierre Blanchard, a Frenchman.

During the 35 years leading up to the 20th century, there were increasing numbers of persons who conceived and patented different types of flying machines, ranging from flying steamships to aircraft with flapping wings. During the 1880s and 1890s, experiments with gliders were carried on by Octave Chanute in Michigan and John J. Montgomery in California. These two probably paved the way for the final invention of the airplane. Montgomery is reputed to have soared aloft as early as 1883. It is an established fact that he made numerous successful flights at Otay Mesa, Calif., in subsequent years. Chanute's book, Progress of the Flying Machine, stirred the imaginations of a number of practical men.

Among these were Prof. Samuel P. Langley, assistant secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and two brothers, Wilbur and Orville Wright, who operated a bicyclerepair shop in Dayton, Ohio. Langley succeeded in building a 13-foot model which flew successfully with a miniature steam engine, but his man-carrying machine of similar design crashed into the Potomac on two futile endeavors to launch it in 1903.

Orville and Wilbur Wright experimented with controllable box kites and gliders until they felt certain they could handle similar craft in powered flight. Not until then did they go about designing and building an engine for their airplane.

It is history that Orville Wright made the first test flight December 17, 1903. He traveled approximately 120 feet and damaged his machine upon landing. The original flight didn't equal the wingspan of a modern four-engined airliner. But don't forget that both Orville and Wilbur had to learn how to fly after they were airborne.

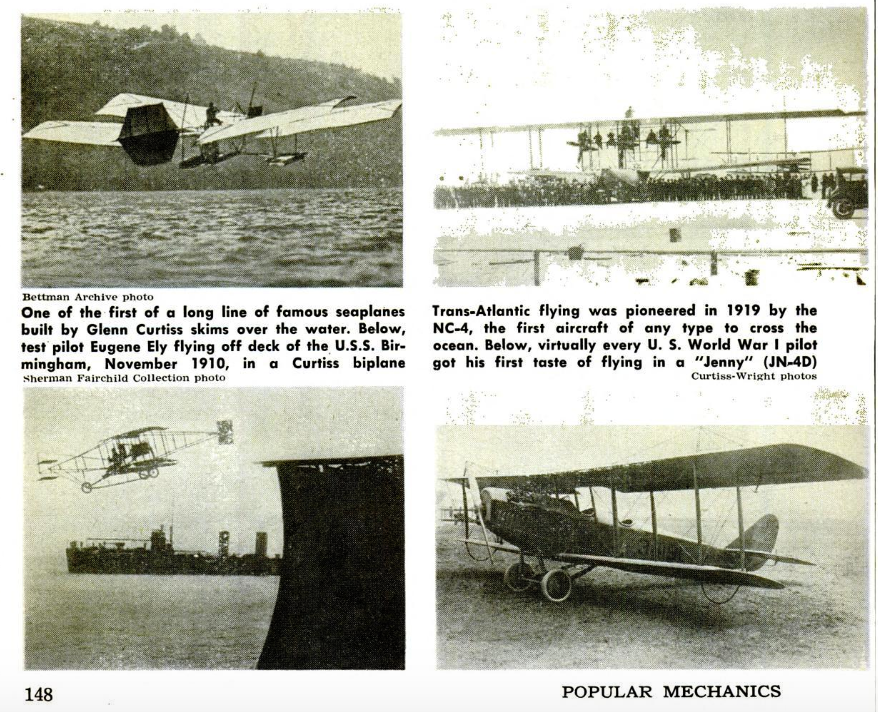

America and the world did not take to the air overnight after the Wright brothers made their flight. As a matter of fact, during the entire year of 1904 the total flying time of the brothers combined was only 45 minutes, although they built a second airplane. The next year they made 50 flights, but during the year 1906 they did no flying whatsoever, devoting all 12 months to perfecting a new engine having vertical, rather than horizontal, cylinders. At the end of 1907 only seven men in the U. S. had flown. In addition to the Wright brothers, they were A. M. Herring, F. W. Baldwin, Lt. Thomas Selfridge, Glenn H. Curtiss, and J. A. D. McCurdy.

✈︎ December 1981: Was Whitehead First?

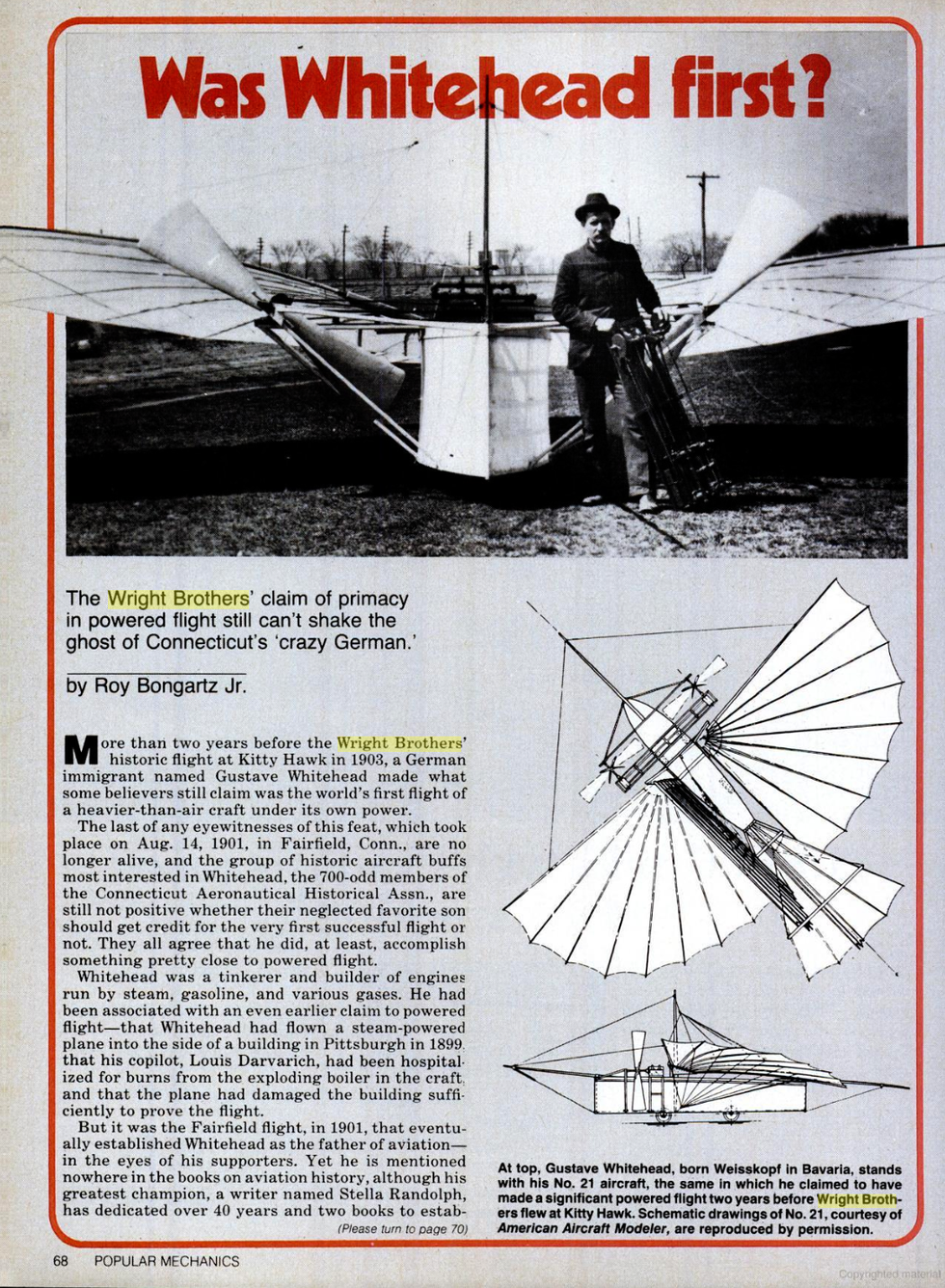

Further confusing those who like history to be organized neatly, Popular Mechanics writer Roy Bongartz, Jr. questioned whether Connecticut's "crazy German" immigrant Gustave Whitehead actually manned the world's first flight on a mechanical aircraft.

History, it turned out, was not so black-and-white as saying the Wrights were first. Two years before the Wright brothers made their historic flight at Kitty Hawk in 1903, Whitehead made a flight in Fairfield, Connecticut that took him 50 feet in the air. It was more or less the lack of photographic evidence, Bongartz wrote, that kept Whitehead from the history books:

A more technical criticism of Whitehead's flights is involved with the question of whether there was any flight beyond that produced by the "ground effect" cushioning of air beneath the wings at low altitudes. [Historian Harvey H.] Lippincott recalls that "no witness said he did much in the way of turning." As for the later seven-mile flight in No. 22, Lippincott says, "We think that's poppycock."

The historian suspects that Stanley Yale Beech, who put money behind some of these flights, exaggerated the claims of success. "He wrote that fiction just to make his own investment in Whitehead look good."

✈︎ September 2003: Was Richard Pearse First?

Following that 1981 piece, Popular Mechanics seemed to have taken a sabbatical from poring over the possible aviators that may or may not have beaten the Wrights to the skies. That is, until 2003, when a quick blurb made mention of a man from New Zealand, whom the country was pretty sure made a mechanical flight before the Wrights:

Does the name Richard Pearse ring a bell? It does if you are from New Zealand, which claims that Pearse, a local farmer, beat the Wright brothers into the sky by nine months. Pearse's bamboo monoplane made a textbook takeoff from his South Canterbury farm on March 31, 1903. And while the plane had an elevator and aileron-like surfaces, it proved impossible to control. Local historians tell Popular Mechanics Pearse's first flight ended on top of a 12-ft.-tall hedge. When the Wright brothers solved the control problem with their wing-warping technique, Pearse fell off the pages of history. His design, however, had some modern elements, including the tricycle landing gear.

From our vantage point, it's still safe to say that the Wrights were first to fly, but it doesn't hurt to brush up on aviation history just in case the skeptics want to joust.