At 16, Craig Chester fell in love with a boy in his suburban Dallas church.

It was the early 1980s—hardly a hopeful time for gay acceptance in the South—and Chester still remembers what his pastor told him when he found out about the doomed love: "God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve." Then he quoted a verse from Leviticus.

"I think my preacher or pastor was the first person I heard saying it," says Chester, who grew up in a born-again Christian family. "There were starting to be gay characters on television. They would have seminars where people would come in and give lectures on what was going on in L.A. and New York and the gay agendas. I remember hearing stuff like that growing up and feeling a lot of shame."'

Chester tried to kill himself soon after, cutting his wrists in the high school bathroom. He's now a filmmaker; the first movie he wrote was the gay romantic comedy Adam & Steve.

For decades, the right-wing fight to keep gay couples from getting married—which culminated in defeat with last Friday's Supreme Court decision—has returned again and again to that single catchphrase: "God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve." Or: "It's Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve." If you were an alien wading into LGBT debates for the first time, you'd think it were a paragon of logic and stone-solid proof. (It's not.) But there's a lot packed into such a succinct homophobic mantra: God. Religion. Mocking same-sex relationships. Idealizing heterosexual partnership as the bedrock of, literally, the human race.

The line dates back further than you might expect, appearing long before same-sex marriage became a viable political goal. And tracing its more recent history reveals a curious trend: LGBT people reclaiming "Adam and Steve" as a positive expression of their own.

The first known appearance of "Adam and Steve" came in 1977, in what would become its natural habitat: a picket sign at an anti-gay rally. This particular protest brought 15,000 "pro-family" spectators to an arena in Houston, where burgeoning Religious Right icons like Phyllis Schlafly and National Right to Life Committee founder Mildred Jefferson railed against homosexuality, abortion and the National Women's Conference happening five miles away. The master of ceremonies was a businessman named Lee Goodman, who proclaimed it the "most significant day in the history of our country" and who died six months ago after being sued for ponzi-scheming more than 50 investors.

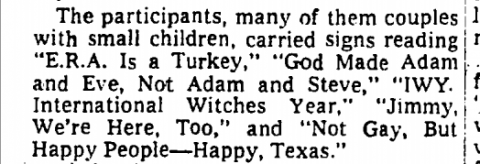

The New York Times published a Nov. 19, 1977 report that quoted some of the protest signs: "E.R.A. Is a Turkey," "Not Gay, But Happy People—Happy, Texas" and, of course, "God Made Adam and Eve, Not Adam and Steve."

Whoever wrote the slogan was probably going for a snappier take on "If God had wanted homosexuals, he would have created Adam and Freddy," which was scrawled by a San Francisco graffiti artist in 1970 and parroted by anti-gay activist Anita Bryant (who swapped out "Freddy" for "Bruce") in People magazine in 1977.

But if you were to guess who first gave the phrase wider national exposure, you'd probably get it right on the first or second try: the late televangelist Jerry Falwell, of "Gays Caused 9/11" fame. Falwell used it in a 1979 press conference that was written up in Christianity Today. In the conservative Review of the News that year, he was quoted as saying, "God didn't create Adam and Steve, but Adam and Eve." By the early '80s, this was being touted as one of the pastor's favorite lines, appearing with slightly different wording in TV Guide and Esquire. (Bizarrely, Martin Amis quoted Falwell's favorite refrain approvingly in a 1980 New York Times book review.)

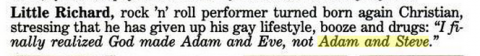

From there, it just spread. Conservative congressman William E. Dannemeyer latched onto the slur, as noted by a 1986 Los Angeles Times profile. A Massachusetts politician, Roger Goyette, used it to block gay rights legislation in 1985. "Adam and Steve" started appearing prominently in books both by and about the thriving Religious Right. "HOMOSEXUALITY: Adam and STEVE" was a chapter title in Michael Youssef's 1986 book "Leading the Way: The Church or Culture?" Strangest of all, rocker Little Richard used it to renounce his own "gay lifestyle." Here's a 1986 appearance in Jet magazine:

Around this time, Craig Chester served as a teen missionary. "We used to go down to the gay bars in Dallas and try to save the gays," he says. After he'd come out and moved to New York, he returned to Dallas and attended a gay pride parade. "There was a group of protesters. They had a 'God created Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve' placard. Because I had been religious, I went over and just had a debate with one of them."

By the 1990s, the phrase was ubiquitous. It popped up twice in Newsweek—including in a 1993 story predicting same-sex marriage—and once in a 1996 New York magazine profile of Senator Jesse Helms. In a 1998 book, religious scholar Rebecca T. Alpert identified it as having become "an important slogan for the antigay movement," noting its presence on placards, bumper stickers and television. Gay-bashing politicians have continued to return to it ever since. In a memorable instance, Parliament member David Simpson botched the quote during a 2013 debate on same-sex marriage in Great Britain. "In the Garden of Eden it was Adam and Steve," he said to unintended laughs.

But something changed in the '90s: LGBT writers and supporters started taking "Adam and Steve" back. In his 1994 novel Just As I Am, the writer E. Lynn Harris mocked the expression. One of the book's characters puts it bluntly: "If I hear God created Adam and Eve not Adam and Steve one more time I'm going to croak. Who thought of that stupid ass shit? Who the fuck is Steve anyway?"

Then, in The Most Fabulous Story Ever Told, a 1998 play by the openly gay playwright Paul Rudnick, God does make Adam and Steve—as well as a lesbian couple named Jane and Mabel.

"I remember that it was very commonly used by a lot of evangelical preachers," Rudnick says. "They'd always be very jolly and condescending, as if you could dismiss all gay lives with a kind of tired punchline." So began The Most Fabulous Story: "I remember thinking one day, what if you took these preachers at their word? What if God did make Adam and Steve?"

Naturally, the "demented romantic comedy" spawned protest among the fundamentalists it was meant to mock. But Rudnick says the strongest objections came from those who hadn't seen it. "I've found that deeply religious people, people who were raised in religious families, are often the greatest fans of the play," he says. "It's been actually a wonderful way into those conversations."

Craig Chester was one such gay person raised in a religious family, and around the time that The Most Fabulous Story appeared, he went undercover at an "ex-gay" camp in order to write a screenplay about the gay conversion movement. At one workshop, a purportedly converted gay man announced that God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve. Another man announced that his name was Adam and his ex-boyfriend was a Steve. "I thought, they were Adam and Steve," Chester says. "This guy and his ex were actually Adam and Steve before he came to try and change who he is.

That realization prompted Adam & Steve, the movie Chester wrote, starred in and directed in 2005: a comedy about—and named after—a couple named Adam and Steve. "God made Adam and Eve, and I'm gonna make Adam and Steve," he says of his thought process. He likens it to how gay people reclaimed the word "queer" in the '90s. "It's a phrase that's been around me my whole life. To take it and make it into the title of a film felt really empowering." Chester remembers filming the gay wedding sequence in 2004: "It was this sad, poignant, kind of sweet day on set, because it was a fantasy sequence." (A real-life Adam and Steve, by the way, married soon after—sort of. Same-sex marriage was not yet legal in New York in 2006. Adam Berger and Stephen Frank's commitment ceremony, and fairytale love story, appeared in The New York Times' weddings page just the same.)

Though hardly a critical success, the movie has changed lives. When Chester's nephew came across it in a video store in Denton, Texas, he decided to come out of the closet. "He saw me—I'm on the cover of the DVD—and he said, 'Oh my God, Uncle Craig is gay and I'm gay.' So he texted me: 'Uncle Craig, I'm gay and I'm happy,'" the director recalls. "People come out via text message now, which is kind of amazing."

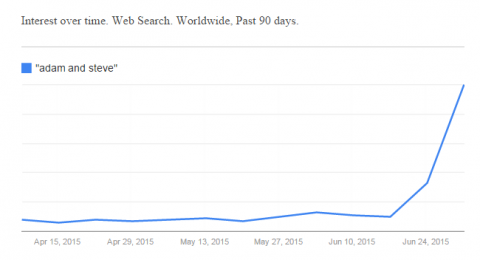

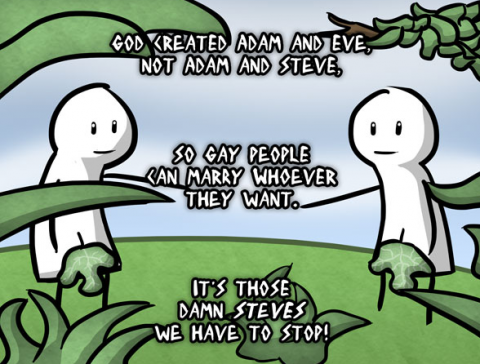

The reclamation of "Adam and Steve" has continued apace in the digital age. Google the phrase today, and you'll mostly find blog posts, cartoons and images of support, not prejudice. NotAdamAndSteve.com is the popular blog of Will Shepherd and R.J. Aguiar, an engaged couple in Los Angeles. (Not to be confused with the similarly minded Meet Adam and Steve.) There's an XKCD comic playing off the trope. There are memes, comics, cartoons and biblically inclined illustrations. Those who do use the slogan in earnest—like this pastor in Georgia—are frequently depicted as unhinged and unreformed. When an Indiana church put up such a sign in 2013, locals spoke up in protest.

In Uniontown, Pennsylvania, Daniel Riggs owns a photography company called Adam & Steve, which specializes in gay weddings and engagements. Riggs, who grew up in Kentucky with a Baptist minister father, wanted to start a business where small-town customers don't feel nervous asking if same-sex couples are welcome. "We were mulling over a name," Riggs says, "and I think probably every person in our LGBT community has heard 'God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve.' We wanted to take something negative and make it positive."

Last week's Supreme Court announcement yielded another flurry of references to the cliché. On Twitter, it provided the setup for celebratory jokes and puns:

It's Adam and Steve not Adam and Dave. They broke up awhile ago. Are you even on Instagram??

— Grant Pardee (@grantpa) June 26, 2015if ur argument for being gay is "Adam and Eve not Adam and Steve" then u need to Adam and leave

— angie (@cumpleted) June 29, 2015Dudes named "Adam and Steve" who're getting married should get like a discount this week or something.

— Guy Branum (@guybranum) June 26, 2015

It's Adam and Eve not Robert and Sarah sorry you two can't get married

— nate zed (@NathanZed) June 28, 2015

Which is not to suggest the earnest "Adam and Steve" invocation is dead—it's out there, and still ugly. It popped up this week in local news broadcasts, gasping newspaper op-eds, rants from pastors, even at New York's Pride Parade, on a sign belonging to an orthodox Jewish group that opposes gay marriage.

But in major media outlets, the phrase surfaces just as often as an emblem of a bygone era. Open-minded Mormons are "bored of hearing about 'Adam and Eve not Adam and Steve,'" the British Metro reported last week. And a Daily News lede on Friday deployed it rather simply.

"Marriage is now legal in the U.S.A. for Adam and Steve," the tabloid transmitted to its readers, "not just Adam and Eve."