It was one of those beautiful, crisp February days in East Texas. Blue, clear skies. A quiet Saturday.

Then, a sonic boom pierced the peaceful morning.

“It shook my house,” Gregg County Judge Bill Stoudt recalled recently, thinking back 20 years ago, to Feb. 1, 2003. He had started his first term as county judge a couple of months earlier.

“That’s how loud it was. Everybody felt it and heard it,” he said. “The first thing most of us thought was that something happened at Eastman.”

Quickly, though, reports began flashing on the morning news program he was watching.

The space shuttle Columbia had broken apart as it re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere. All seven astronauts on board died.

Pieces of the shuttle rained down across deep East Texas — mostly in Nacogdoches, Shelby, San Augustine and Angelina counties.

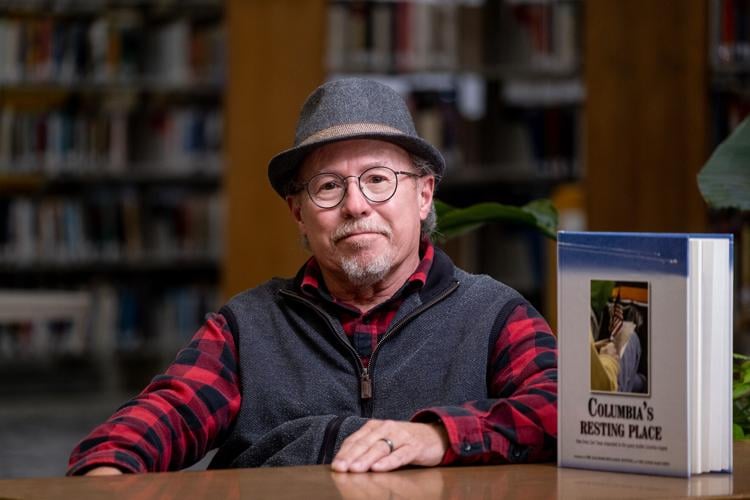

Former News-Journal Publisher Gary Borders was, at that time, editor and publisher of the Nacogdoches Daily Sentinel and editor of the Lufkin Daily News.

He was 46 at the time and described himself as the “old guy” among his staff. He said he was heading into the office that morning when he heard the loud boom but thought it was probably an accident. He had stopped at his usual coffee spot when the phone rang there at the business, bringing with it news of Columbia.

“I drove as fast as I could to the paper and started calling everybody I could find to come to work,” he said.

Then, he sat down to write one of the first stories that would be distributed across the news wires about the tragedy that unfolded over the skies of East Texas.

It wasn’t long before people started calling law enforcement and the Daily Sentinel, reporting finding pieces of the shuttle in their yards and around Nacogdoches.

“It was kind of clear to me it was going to affect Nacogdoches for a long time,” Borders said.

While the staff at his two newspapers went to work, they were soon joined by other journalists from other organizations who set up in the Daily Sentinel’s building — the Associated Press, metro newspapers and broadcast media.

Border’s newspapers started publishing stories online as quickly as possible to keep the public informed about what was happening.

“We worked almost nonstop for a good 10 to 14 days,” Borders said.

‘This is horrible’

Current Longview Fire Chief J.P. Steelman had started working for the Longview Fire Department 12 years earlier.

He got off shift that morning and was driving home when he heard news about Columbia. By the time he got home, to Gilmer at that time, television news was broadcasting video of the breakup as the shuttle re-entered Earth’s atmosphere.

“This is horrible,” Steelman, a self-described space nerd, recalled thinking. “I can remember being in high school in ‘86 when the Challenger exploded. I couldn’t believe something like this had happened again.”

While Longview didn’t see as much debris from the shuttle’s breakup as areas south of Longview, no one knew that at first.

“It got kind of busy. We got busy running debris calls,” Steelman said. For every piece of anything on the ground — a scrap of a blown tire or a piece of metal — the question of whether it was from the shuttle had to be answered.

“The people didn’t know. People knew this thing had scattered and dropped all over the state...” Steelman said, so emergency personnel would respond to calls about potential shuttle debris and try to determine what something was or if it needed to be referred to law enforcement.

Soon, though, Longview and Gregg County stepped into a key role in the recovery process because of the East Texas Regional Airport. The site was chosen as the “national logistics hub” for the recovery effort.

“East Texas, for myself, and many other folks (with NASA) holds a very special place in our hearts,” said Michael Ciannilli. In 2003, he was a test project engineer assigned to Columbia, overseeing launch vehicle processing. He also was in the firing room on the Columbia launch team for STS-107, the designation for that space shuttle flight.

Initially, after the accident, he came to Texas as part of a helicopter flight team, performing extensive search and recovery air operations in the Palestine area. Later, he returned to Texas to lead Lufkin air operations for the remainder of the Columbia recovery effort.

The experience, he said, was overwhelming and challenging.

People like him, who were responding to Texas, first were dealing with the loss of people they knew, friends.

“The shock and emotional impact hits you very strong,” Ciannilli said. “At the same time, we had to immediately jump into a response mode.”

Those two things were happening at the same time, while the scope of what they were dealing with began to take shape.

“We were learning that real time,” he said, with the initial reports about the size of the field of Columbia artifacts, the volume of items on the ground, getting larger and larger. It was “increasing as each hour went by.”

A team was on the ground in East Texas that day and began piecing together how they would do something that had never been done before. No space shuttle had every been through anything like that before, Ciannilli said, and they had to put together a recovery effort in an area unfamiliar to them, in terrain they didn’t know, in a place far from their own resources.

“It truly was a partnership to get our hands around it,” to understand the situation, he said, recalling the relationships that quickly developed between local, county, state and federal officials.

Stoudt said local officials had no idea at first that Longview would become a major collection point for shuttle wreckage in Northeast Texas, or the role the East Texas Regional Airport outside of Longview would play as part of the recovery efforts — C130 transport planes, vans arriving by air to take people out into the field, personnel flying into the airport.

“It happened very quickly. We just had a lot of people here real quick,” Stoudt said.

‘Down to business’

One of the first things local officials helped with was the identification of a warehouse, on Cotton Street across from the former Stroh Brewery, to bring Columbia artifacts collected throughout Northeast Texas before they completed their journey to NASA.

“Our main role was that airport.... the number of flights in and out of that airport, it will amaze you,” Stoudt said.

The county focused on security at the airport and making sure the recovery effort had everything it needed.

“After we got through the shock and the horror of the whole event, then it was down to business,” Stoudt said. “Everybody just strapped in and did their job. If somebody asked us for something, we didn’t say we can’t do it. We found a way to do it,” he said.

The recovery effort was important, Stoudt said.

“In my mind, it was a national tragedy. That space program had so many bright spots,” and brought with it a whole new era of technology and space exploration, he said. “To have these men and women just blow up in the sky — it needed to be dealt with, and we needed to find out the reason.”

The fairgrounds at the Maude Cobb Convention and Activity Center served as a base camp where U.S. Forest Service personnel from Georgia and North Carolina and Texas Forest Service personnel stayed and mobilized for the search each day.

Steelman recalled watching that process. Wildland firefighters arrived at the airport, he said. Some camped at the fairgrounds, where there were showers, bathrooms and tents set up. Others stayed in hotels for their 14-day assignments.

“It was fascinating, and getting to be a fly on the wall and watch that all unfold. I went out there as a student,” he said.

Longview Fire Capt. Kolby Beckham was among a group of Longview firefighters, most of whom were in the special operations unit, who volunteered in the early days of the search to take their four-wheelers to Angelina County to help look for shuttle pieces in the deep forest.

“It was a significant event in America, and it was in our backyard,” Beckham said, explaining that they volunteered because they had a sense of duty to assist.

They were assigned a specific grid to search — each team had to be accompanied by a law enforcement officer. A large map was updated each day to show were items had been located.

“You could make out that trail of debris and how it ran through the county there,” Beckham said.

He described finding “very small debris” that was less than 6-8 inches long, pieces of foam board and 2- or 3-inch pieces of the shuttle’s outer shield.

“The amount of debris that can come from an object and how it can scatter over such a large area was kind of mind boggling,” Beckham said.

Borders praised his young staff and the job they did during those weeks, documenting East Texas’ response to the tragedy, while he was in the office directing coverage.

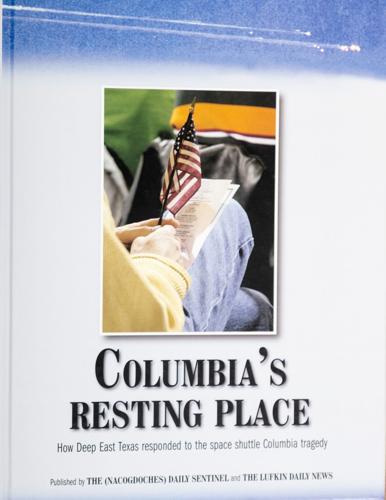

“Exactly 90 days later, we published a book with all of our articles,” he said, with $5 of every sale of “Columbia’s Resting Place” going to a shuttle memorial. “We sold 7,000 books.... That was nice to be able to do that and to be able to have a permanent record of the recovery effort.”

His staffs’ efforts writing about those moments in history reinforced his belief about the importance of journalism, he said.

‘Unsung heroes’

Ciannilli praised East Texas.

“An amazing and beautiful part of the story was all the residents of East Texas, the citizens of East Texas that just rose up and helped us in so many different ways and became true partners in the recovery effort and a very important part of the NASA family through that period,” he said.

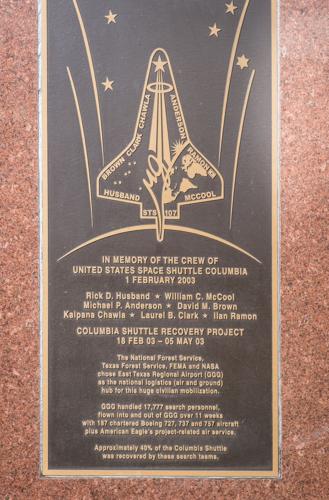

In 2004, NASA commemorated the lost shuttle crew and the recovery effort in a monument placed at the East Texas Regional Airport, which is known as GGG. It notes the airport handled 17,777 search personnel, flown into and out of GGG over 11 weeks with 187 chartered Boeing 727, 737 and 757 aircraft plus American Eagles’ project-related air service.

“Approximately 40% of the Columbia Shuttle was recovered by these search teams,” the monument says.

Something like the Columbia effort had never been done before, Ciannilli said, describing it as the “largest ground search in American history.”

“We learned a lot. In the general sense, looking back at it, you can say the entire Columbia recovery effort, upon reflection, is probably a tremendous textbook case example of how to do a mass recovery effort like that.”

In the present, that’s important for more than one reason. Today, Ciannilli is program manager of NASA’s Apollo Challenger Columbia Lessons Learned Program.

“It truly was honestly a massive lesson learned. We learned all of that. We hope and pray we never have to do anything like that again,” he said, but those experiences are now something NASA shares with commercial space companies and other organizations. Those lessons are used to help organizations prepare to respond to their worst day.

That program brings light to the “dark story” of the Columbia tragedy, he said, adding that “Columbia is still flying a mission.”

East Texas, he said, was essential to bringing the Columbia and its crew home. He described how people here were important to helping in the search, with their expertise on and access to the land. It helped make the process more efficient and safe for searchers.

But East Texans gave something else as well. He recalled that when he wasn’t flying in helicopters, looking for debris, he would be given a list of people to visit, who had found debris on their property. He recalled sitting down with them, in living rooms or at dining room tables.

“These folks just poured out their hearts, they poured out the most hospitality you could imagine,” Ciannilli said. There were lots of hugs, he said, words of encourage and support.

“We didn’t expect this going in. From an emotional point of view, they reached out,” he said, and for the people who were still grieving and working through long days in a difficult mission, that was “invaluable.”

“They’re truly the most unsung heroes,” of the recovery effort, he said

The connection he saw among Americans then was “poignant and powerful” as NASA employees and East Texans came together around the loss of the Columbia, with one mission based around one, common American loss.

“It felt like one big American family coming together to help. It felt neighborly. It felt amazing,” he said.

He hopes people see that when they look back on this time.

“We didn’t see differences, but we saw ways to help each other and do what we needed to do for the country,” Ciannilli said.