Editor’s Note: This article includes depictions of nudity. It was published in partnership with Artsy, the global platform for discovering and collecting art. The original article can be seen here.

Divinely inspired or otherwise, the Old Testament story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden is deeply rooted in the Western psyche. Eve occupies mere pages of the Genesis epic, but women have spent millennia atoning for her original sin. For the last 2,000 years, Eve has been invoked in the monotheistic world to suppress women’s rights and defame their characters. How many misogynistic stereotypes and prejudices stem from the reputation of the much-maligned, archetypal first woman?

The apostle Paul cited Eve’s narrative to justify women’s subservience to men, writing in the apocryphal book of Timothy that women should “keep silent” because “Adam was formed first, then Eve. And Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor.”

In the Middle Ages, St. Bernard of Clairvaux sermonized to rapt audiences of men and women that Eve was “the original cause of all evil, whose disgrace has come down to all other women.” More recently, at a legislative dinner in 2015, South Carolina Senator Tom Corbin was confronted for his combative remarks about women’s right to participate in the state’s General Assembly. “Well, you know God created man first,” he quipped. “Then he took the rib out of man to make woman. And you know, a rib is a lesser cut of meat.”

From these rigid perspectives, Eve is one-dimensional: inherently wicked and an afterthought to Adam. Yet across popular culture and the history of art, Eve appears as a paradox. She is guileful and naive, earth mother and fatal seductress; she is the problem of man, his downfall, his eternal scapegoat.

Such depictions have structured our ideas of beauty, gender, and morality. The oldest conceptions of Eve play out again and again in all reaches of contemporary culture. A judiciously placed apple in a woman’s hand in art, advertising, or film can immediately invoke Eve’s devious sexuality, and still other references abound. The Handmaid’s Tale (2017–ongoing), adapted by Hulu from Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel, features a young, religious character named Eden, who is expected to help repopulate the country. By the same token, in Pixar’s animated children’s movie WALL-E (2008), the title robot meets a fellow android who has come to bring new human life to Earth. Her name? EVE.

Forbidden fruit

Though never explicitly named in the Bible, the apple has become the de facto “forbidden fruit” – powerful nomenclature for that which is fatally desirable, and therefore all the more tempting and worthy of moral rule-breaking. The apple’s shiny red skin and juicy interior make it an apt stand-in for sex, and the seductive way in which Eve is often depicted eating it only reinforces its libidinal connotations.

Genesis records that after Eve takes a bite of the fruit, she simply “gave some to her husband and he ate.” St. Jerome, however, used the Latin word seducta to describe Eve’s transgression.

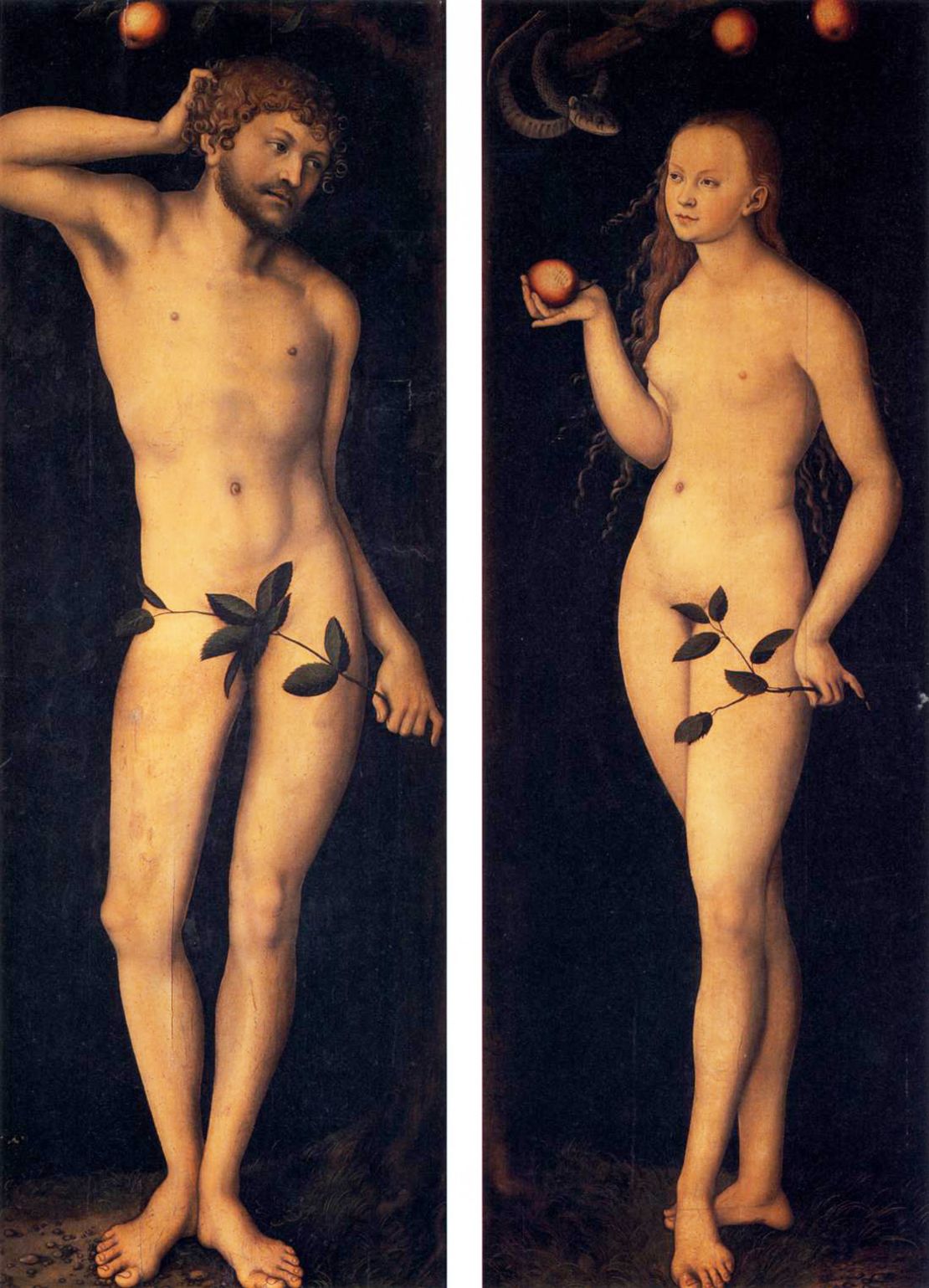

During the Northern Renaissance, German artist Lucas Cranach the Elder perfected the bewitching female nude. In his Adam and Eve diptych from 1528, the couple faces one another beneath the Tree of Knowledge, little red apples bobbing tantalizingly above their heads. A self-possessed Eve holds one perfect fruit out to her husband, who scratches behind his ear in apparent befuddlement. In Cranach’s depiction, it’s not the serpent whispering in Eve’s ear or even the apple that is dangerous, but the perfectly beautiful and alluring woman who will be his pleasure – and his downfall.

Men are often shown as helpless in the face of this female threat. In Domenichino’s 1626 painting, “The Rebuke of Adam and Eve,” God and his coterie of cherubim float down from heaven to reproach Adam. The first man throws up his hands in what looks like confusion or exasperation, diverting the entirety of the blame to his wife.

The image of Eve as sexual temptress has remained frighteningly constant, even in products and programs that purport to challenge ingrained sexist tropes. In the early aughts, for example, the soapy comedy-drama “Desperate Housewives” was lauded for casting five middle-aged women in the lead roles. The intended audience for the salacious TV show was presumably women, yet the impossibly fit, botoxed, and high-heeled characters seemed designed to appeal to men.

The apple’s shiny red skin and juicy interior make it an apt stand-in for sex, and the seductive way in which Eve is often depicted eating it only reinforces its libidinal connotations.

Red apples played prominently in promotional materials for the show. In the title sequence, an animated version of Cranach’s Adam is crushed by a giant falling apple as a blasé Eve looks on. In posters ahead of season five, the topless cast smiles coyly from behind a row of apples and the tagline “Even Juicier.”

So should one eat the apple or abstain? Designer Donna Karan exploited this ambiguity for her long-running DKNY scent “Red Delicious.” In the ads, a pouty model has just bitten into a green apple (how subversive), and the perfume packaging itself is shaped like the fruit. Sin is no longer the province of Eve alone: The “new temptation in fragrance” was marketed to both women and men.

Once in a while, the story of a woman with an apple doesn’t explicitly end with damnation or sex. In Disney’s “Aladdin,” the apples Princess Jasmine steals for a young, hungry boy lead to her meeting the titular male hero. They go on to have fabulous adventures together, but it’s Aladdin who reveals the world to Jasmine, and not the other way around. Sometimes apples – potent transmitters of dangerous information – are exchanged between women. In the 19th-century fairy tale that would later become a Disney classic, a witch proffers the poison apple that puts Snow White to sleep.

Snake charmer

In the book of Genesis, the tempting creature is explicitly referred to as “he” and is described only as a serpent. Yet Eve’s casting as an evil temptress gave rise to the belief that the duplicitous snake was female, too. In art, it was often depicted with a womanly upper body and a reptilian lower half. If wickedness is associated with femininity even before Eve gives Adam the Forbidden Fruit, which came first, woman or sin?

Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel version of “The Fall of Man” sees his muscular Adam and Eve joined by an equally hulking snake-woman wrapped around the tree. Her right arm grasps the trunk for support as she stretches out to meet Eve’s upraised hand. Both Eve and the serpent use their left, or “sinister,” hands, further signaling their deviousness.

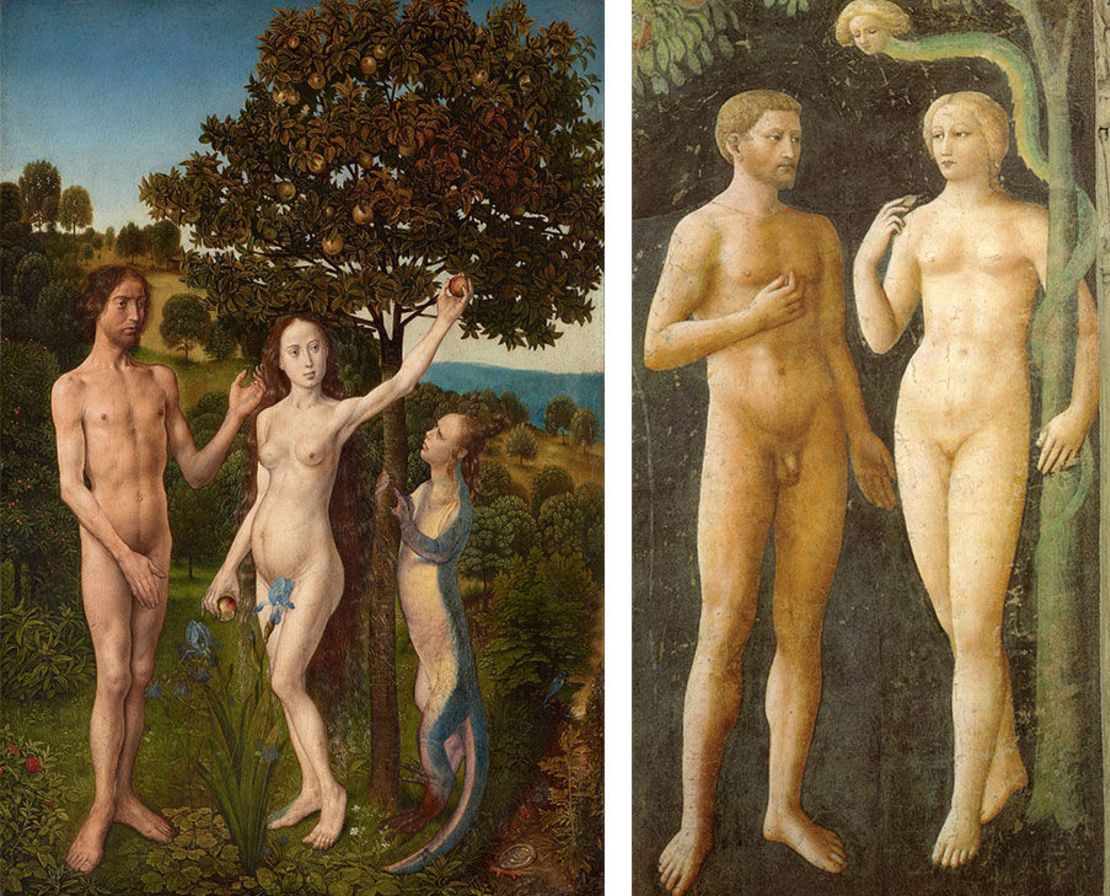

Michelangelo was merely following a popular convention of his time. During the Renaissance, snake-women appear in Hugo van der Goes’s “The Fall of Man” and “The Lamentation” (ca. 1470–75); a terracotta sculpture of Adam and Eve by the workshop of Giovanni della Robbia (ca. 1515), which took inspiration from a famous Albrecht Dürer engraving; and the stone facade of Notre Dame. A blonde-headed serpent woman in Masolino’s “Temptation of Adam and Eve” (ca. 1425), a fresco in Florence’s Santa Maria del Carmine, is frighteningly funny: She snakes along the Tree of Knowledge with her comically tiny head popping out of the end of her skinny green body.

Even before the Bible story, snakes were associated with women in cultures around the globe. The hostility that is created between them in the Bible may have been a way to separate the nascent Jewish community from pagan traditions that had a snake as a powerful female goddess. The Canaanite cult of Baal-Asherah heavily influenced the newly formed Israelite nation. In the predominantly female cult, Baal appeared in the form of a serpent with his wife, Asherah, at his side. When the Israelites entered Canaan, pagan religions were demonized in lieu of monotheism.

In this light, the story of Adam and Eve has political undertones. The biblical narrator may have already witnessed an established association between the serpent and the woman in neighboring tribes. When God punishes them, a wedge is driven between the serpent and the woman, cursing everlasting “enmity” between them and their offspring. The story successfully alienates the woman from her longtime ally.

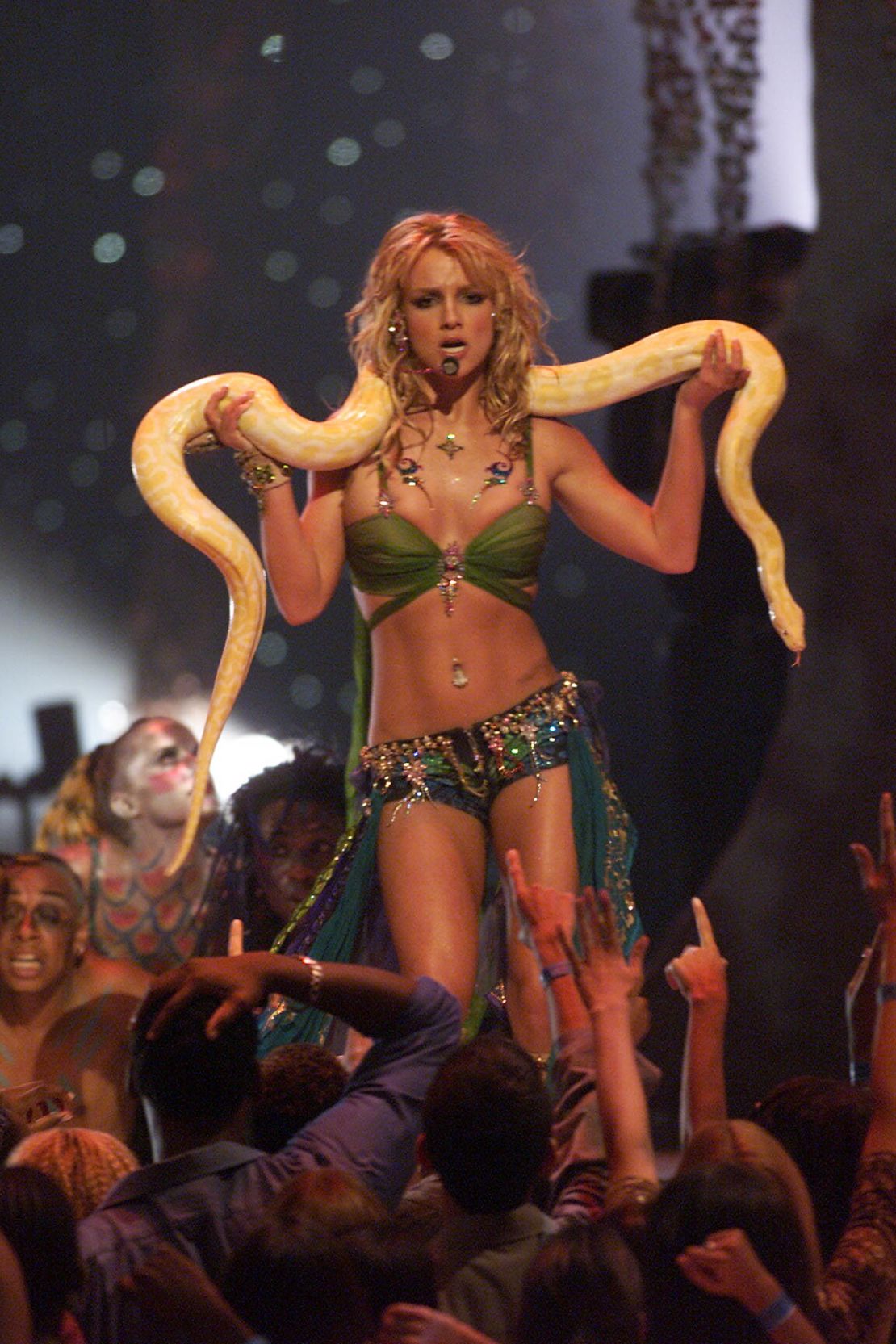

They are indeed powerful together. Who can forget the 2001 MTV Video Music Awards, when Britney Spears walked onstage with an albino python draped across her neck? Dressed as an exotic snake charmer and scantily clad in artfully tattered rags and glitter, Spears fully assumed her onstage persona as an outlet to embrace her newfound sexual freedom. The conflation of the pop star with a sexual goddess transpired before millions of girls and women in the public forum of television. With that scene from Genesis, snakes and women received their eternal reputation of immorality. The snake became an erotic symbol as “the bad girl” gained sex appeal.

The fall of (wo)man

Spears’s performance resonates with an artwork made over a century earlier by Pre-Raphaelite painter John Collier. With her perfect, naked body and long blonde hair, the woman in the 1887 painting who nuzzles the head of the giant snake sensually coiled around her looks like Eve. But in fact, it’s her alter ego, the legendary femme fatale, Lilith.

Fed-up women looking for a new matriarchal origin story have taken in Eve beneath their own gaze. They have embraced the qualities – independence, curiosity, sexuality – that once demonized her.

In Jewish literature, the enchantress Lilith is described as Adam’s first wife, before Eve. Lilith was man’s equal but was devilish in her sexuality. According to legend, she felt repressed by Adam’s side, and she eventually leaves him to cohabit with demons in deep waters. In folklore and pop culture, she has come to be known as the mother of demons and vampires, eater of babies, husband of Satan – in short, a dangerous, sexually liberated woman.

Lilith appears in many guises in TV and movies: the progenitor of the vampire race in “True Blood” (2008–14); Madam Satan on “The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina” (2018–ongoing); the frigid, hated ex-wife of sitcom icon Frasier. The sci-fi movie “The Fifth Element” (1997) turns the concept of Lilith on its head by having the main character Leeloo – a variation on Lilith – save humanity instead of devouring it. Her name has also been invoked as a statement of feminist independence: “The Lilith Fair” of the late 1990s adopted the legendary woman’s name for a music festival that showcased only female artists or woman-led bands.

One recent TV show has gone above and beyond in complicating our understanding of Eve, and women. The BBC series “Killing Eve” (2018–ongoing), which follows an M15 agent, played by Sandra Oh, as she tracks down a psychopathic female assassin portrayed by Jodie Comer. Guess who is Eve? It’s not the assassin.

The delight of the show is seeing the intense connection unfold between the so-called good and bad guys. Who is on which side becomes impossible to understand – both women contain multitudes. The sexual drama lies between the killer, Villanelle, and Eve – not a man. Though the title of the show probably refers literally to Villanelle’s overarching plans, it’s also a fitting metaphor for the destruction of the story of Eve itself – and all the misery, unfair expectations, and misrepresentation that have come along with it.