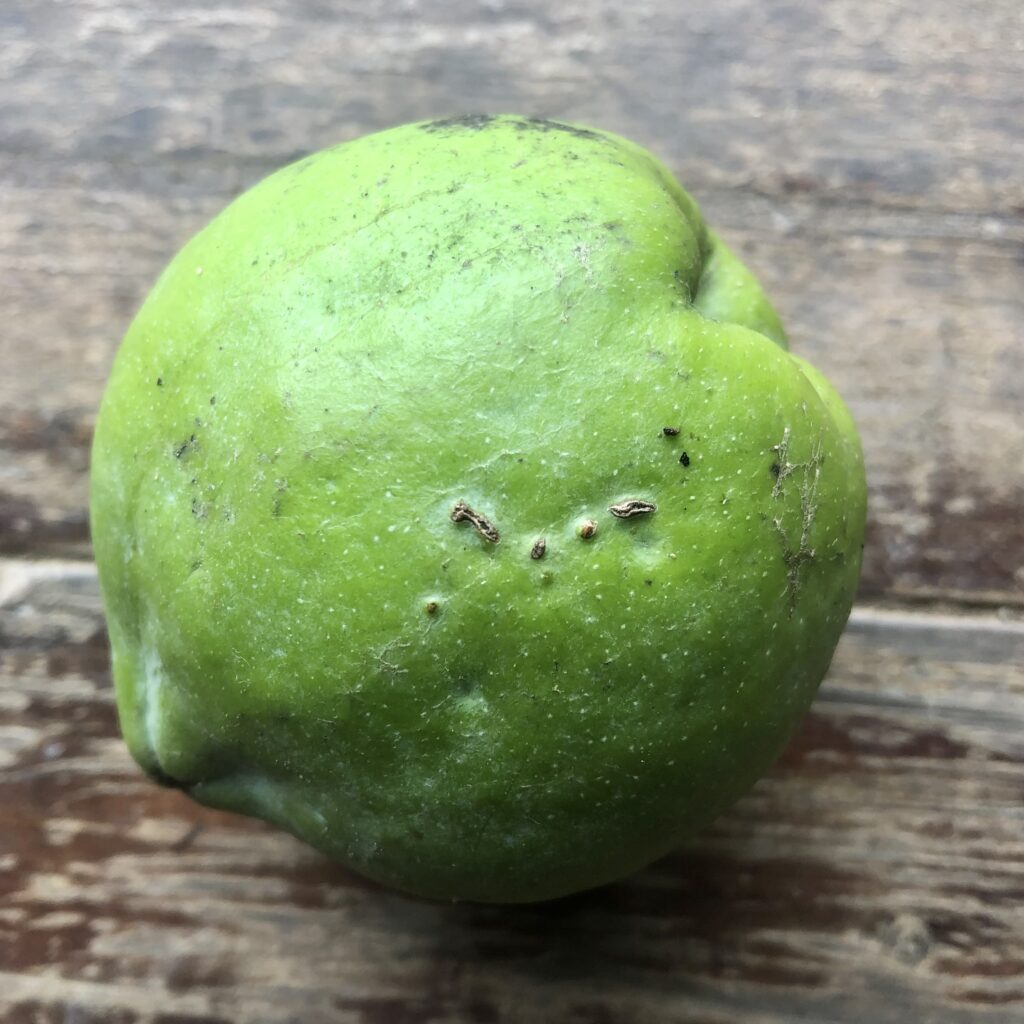

We’re at the end of white sapote season here in southern Ecuador. The last of the many fruits I’ve purchased at the local organic market since October has been ripening on the counter for some weeks now, and will be savored when it turns soft. White sapote is one of my favorites and enjoying the last fruits of the year is bittersweet.

It has become an annual ritual for me to plant some of the seeds from the white sapotes I eat that year. I first soak them, changing the water every day or so, until they finally crack open. Then they are planted into small bags in the greenhouse. I transplant them into larger bags in a few months, and then plant them out into the gardens when the rains come the following year. Trees grown from seed can take 7-8 years to fruit, so it will still be a few years before we can enjoy sapotes from the trees we’ve planted.

Casimiroa edulis, also known as zapote blanco, casimiroa, or Mexican apple, is an tropical tree in the Rutaceae family. It is native to Mexico, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua (Royal Botanic Gardens, 2017).

White sapote is cultivated for its incredibly delicious fruit that is creamy and sweet, like a custard. The green to yellowish skin is removed and the white flesh is eaten.

The fruits are are a source of vitamins B1, B2, B3, & C, as well as phosphorus and other nutrients. They are typically eaten raw, but can also be used in juices, smoothies, fruit salads, preserves, pies, or ice cream (Satheesh, 2015).

The tree is utilized as fire wood, and is said to improve soil fertility. It’s also used along fence lines and for providing shelter for livestock (Satheesh, 2015). In Central America, white sapotes are planted as shade for coffee trees (Orwa et al., 2009). In California, they are grown as ornamentals (Morton, 1987).

The fruit contains several large whiteish seeds, which some sources say are fatally toxic to humans and animals if consumed raw (Morton, 1987). Folk herbalism practices, however, do utilize the seed, as well as other parts of C. edulis for medicinal purposes. As with most things, it is very likely the dose and preparation that makes the difference.

In traditional Mexican herbalism, extracts from the seeds, leaves, & bark are utilized as a sedative, to help ease insomnia and promote restful sleep. (Vidal Lopez et al., 2008). The Aztecs called C. edulis “cochiztzapotl,” which means “sleepy sapote” (Orwa et al., 2009).

In Mexico and parts of Central America, is said that eating the fruit helps ease arthritic pains. The fruit is also eaten to help eliminate intestinal worms. In Costa Rica, a decoction of the leaf is taken for diabetes (Orwa et al., 2009). White sapote is also utilized for lowering high blood pressure (Vidal Lopez et al., 2008).

Due to its uses in folk medicine, research has further investigated the potential of this plant for medicinal applications. One animal study found that an extract of C. edulis leaves has sedative and antidepressant effects (Mora et al., 2001). Several studies have found that water and alcohol extracts of the leaf and seed lowered blood pressure and caused a “sleep-like stage” in various animal species. Lozoya et al. stated that these extracts also had “a definitive oxitocic effect,” meaning that they stimulated uterine contractions (1977).

Studies have identified constituents in C. edulis that have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antitumor properties (Elkady et al., 2017), as well as sedative, antispasmodic, and anesthetic effects (Millera et al., 2009).

White sapote produces delicious fruits and has an array of healing & practical applications. It’s truly one of my favorite tropical fruits.

References

Elkady, W.M., Ibrahim, E.A., Gonaid, M.H., and El Baz, F.K. (2017). Chemical Profile and Biological Activity of Casimiroa Edulis Non-Edible Fruit Parts. Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 7(4), 655–660. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5788222/#!po=63.9535

Lozoya, X., Romero, G., Olmedo, M., & Bondani, A. (1977). Farmacodinamia de los extractos alcohólico y acuoso de la semilla de Casimiroa edulis [Pharmacodynamics of alcoholic and aqueous extracts from the Casimiroa edulis seed]. Archivos de investigacion medica, 8(2), 145–154. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/334096/

Millera, S.L., Haberb, W.A., and Setzera, W.N. (2009). Chemical Composition of the Leaf Essential Oil of Casimiroa edulis La Llave & Lex. (Rutaceae) from Monteverde, Costa Rica. Natural Product Communications,4(3), 425-426. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1934578X0900400322

Mora, S., Diaz-Veliza, G., Lungenstrassa, H., García-Gonzalez, M., Coto-Morales, T., Polettic, C., … J. Tortoriellod. (2001). Central nervous system activity of the hydroalcoholic extract of Casimiroa edulis in rats and mice. Universidad de Chile. https://repositorio.uchile.cl/bitstream/handle/2250/127221/Mora_S.pdf;jsessionid=49B92C7DA733B17EBF8D5D3E204A88F3?sequence=1

Morton, J. 1987. White Sapote. Fruits of Warm Climates, 191–196. Retrieved from https://hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/white_sapote.html

Orwa, C., Mutua, A., Kindt, R., Jamnadass, R., & Anthony, S. (2009) Casimiroa edulis. Agroforestry Database: a tree reference and selection guide, version 4.0. World Agroforestry Centre, Kenya.

Royal Botanic Gardens. (2017). Casimiroa edulis La Llave. Kew: International Plant Names Index and World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Retrieved from https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:771774-1

Satheesh, Neela. (2015). Review on Distribution, Nutritional and Medicinal Values of Casimiroa edulus Llave-An Underutilized Fruit in Ethiopia. 15. 1574-1583. 10.5829/idosi.aejaes.2015.15.8.9585.

Vidal López, D.G., Schlie Guzmán, M.A., González Esquinca, A.R., Cazáres, L.L. (2008). El zapote blanco (Casimiroa edulis La Llave et Lex, Rutaceae): un recurso medicinal de México. Lacandonia,115-122. https://repositorio.unicach.mx/bitstream/handle/20.500.12753/1779/Lacandonia%20Año%202%2C%20vol.%202%2C%20núm.%201%2C%20junio%20de%202008%20%28arrastrado%29%2011.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y