A lot of choice, during this (so far) mild winter. I wondered about Sycopsis chinensis, of which the yellow filaments are currently glowing @CUBotanicGarden, or one of my own winter-flowering clematis, but – not only because it is glorious in its own right, but because of its role as a sentinel at the entrance to the Winter Garden at the Botanics, which celebrates its fortieth anniversary this year – I’m going for Daphne bholua ‘Jacqueline Postill’, possibly the most famous of the daphnes, not only for its flowers but for the unmistakable fragrance which you walk into like an invisible wall, even on the coldest day, as you approach the plant.

A lot of choice, during this (so far) mild winter. I wondered about Sycopsis chinensis, of which the yellow filaments are currently glowing @CUBotanicGarden, or one of my own winter-flowering clematis, but – not only because it is glorious in its own right, but because of its role as a sentinel at the entrance to the Winter Garden at the Botanics, which celebrates its fortieth anniversary this year – I’m going for Daphne bholua ‘Jacqueline Postill’, possibly the most famous of the daphnes, not only for its flowers but for the unmistakable fragrance which you walk into like an invisible wall, even on the coldest day, as you approach the plant.

Flowers of Sycopsis sinensis in the Botanic Garden.

My Clematis cirrhosa.

To my complete surprise, ‘Jacqueline Postill’ is younger than the Winter Garden. It is (deservedly) hugely popularity, but it was introduced by Hillier Nurseries only in 1982, having been bred by Alan Postill and named after his wife. Postill has worked as a plant collector and breeder for Hillier’s for over fifty years: his other introductions include Choisya x dewitteana ‘Aztec Gold’ and Digitalis purpurea ‘Serendipity’.

Digitalis purpurea ‘Serendipity’, a finalist in ‘Plant of the Year’ at the Chelsea Flower Show in 2010.

Winding back a bit, Daphne was the botanical name given by Linnaeus in 1753 to plants of the laurel family, because Δάφνη is the Greek for ‘laurel’ – it got its name of course from the nymph who escaped the clutches of Apollo by being turned into a tree from whose leaves the god of music subsequently made his crown.

The metamorphosis of Daphne, as imagined by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680).

(In Italy, anyone with a university degree is a laureato/a, as being crowned with a laurel wreath used to be part of the degree ceremony. I once attended a degree ceremony of King’s College London in the Barbican Theatre: one of the officiating dignitaries wore a laurel wreath but I have no idea why.)

Daphne bholua ‘Jacqueline Postill’ in full flower.

Linnaeus recognised ten species of Daphne, including Daphne mezereum, and Daphne laureola, both of which (unhelpfully) can be called the spurge-laurel, and both of which are native to Europe and North Africa. Things got a bit more exciting with nineteenth-century discoveries in the Himalayas and China: the genus expanded rapidly to include between 75 and 90 species (some of which have later been reclassified), while the current number of ‘Accepteds’ on the Plant List is 110.

Daphne mezereum.

Daphne laureola.

Some binomials have a familiar ring: there is a Daphne reginaldi-farreri (named in 2001), and Daphne kingdon-wardii, collected by its eponym in 1938, but identified as a separate species only in 2000. Daphne odora was named by Thunberg in 1784. I have the familiar variety Daphne odora aureomarginata in my garden: the shrub is now over 30 years old and has to be pruned fiercely to keep it in bounds, but it never disappoints at this most lowering time of the year.

Daphne odora aureomarginata.

If I knew then what I know now, I might have got a ‘Jacqueline Postill’, if only because it would be easier to control, but on the other hand, D. aureomarginta is one of the few variegated shrubs that I like.

Daphne bholua ‘Jacqueline Postill’ in the Botanic Garden this week.

Daphne bholua was first described in 1825 by Francis Buchanan-Hamilton (1762–1829), but under the strict rules of botanical nomenclature, David Don (1799–1841, professor of botany at King’s College London and librarian at the Linnean Society) who edited the work in which it first appears, takes the taxonomical credit. Its title is even more ponderous than usual: Prodromus Florae Nepalensis, sive Enumeratio Vegetabilium, quae in Itinere per Nepaliam Proprie Dictam et Regiones Conterminas, Ann. 1802-1803. Detexit atque legit D. D. Franciscus Hamilton, (olim Buchanan) M.D. London. This did not at first ring any bells with me, but another of his works did: the three-volume 1807 Journey from Madras through the Countries of Mysore, Canara, and Malabar, which in a former life my team reissued.

The title page of the Prodromus.

Buchanan was the fourth and youngest son of a Perthshire landowning family – M.A. Glasgow 1779 and M.D. Edinburgh 1783 – who joined the East India Company as a surgeon in the hope of being able to botanise in the East. (Sadly, I can’t find any image of him.) One can only imagine his frustration at being assigned to ship duties for the following ten years, but in 1794 he got a post on land, in Bengal. In 1795 he accompanied the first British diplomatic mission to the kingdom of Ava (in modern Burma), and began a Burmese herbarium.

In 1800, Lord Wellesley (elder brother of the more famous Wellington) appointed him to survey the newly conquered kingdom of Mysore, which resulted in the volume mentioned above, and another herbarium.

Richard, Marquis Wellesley, from the studio of Sir Thomas Lawrence. (Credit: the Government Art Collection)

Then in 1802 there was another diplomatic enterprise, to Nepal, and another herbarium … Wellesley not only made Buchanan his own personal physician, but also put him in charge of ‘the Natural History Project of India’, intended to seek out and categorise all the birds, mammals and fish of the subcontinent.

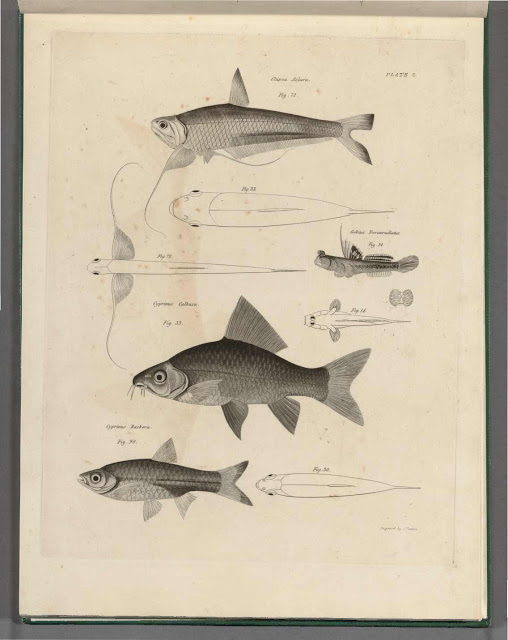

A page of illustrations from another of Buchanan’s publications, An Account of the Fishes Found in the River Ganges and its Branches, etc. (1822).

Unfortunately, Wellesley then fell out with the EIC and returned to England: Buchanan was part of the fall-out and went back with him, though he was sent out again in 1807 to carry out a survey of Bengal.

This task took several years, and apparently cost £30,000. His manuscript was duly delivered to the EIC, who ignored it until it was eventually published by R.M. Martin, in three volumes, in 1838, under the title of The History, Antiquities, Topography, and Statistics of Eastern India.

What Buchanan had always wanted was to be superintendant of the Calcutta Botanic Garden, but when he finally achieved the post in 1814, he left it after a year (probably for health reasons) and retired back to Britain, where he spent much of his time writing. In 1818, the death of an elder brother led to his inheriting the estate of his mother, Elizabeth Hamilton – it was at this point that he changed his name, though he also later established a claim to be chief of the clan Buchanan. (The Hamilton estate was encumbered with £15,000 of debt, which he cleared in his lifetime.)

The title page of Buchanan’s claim to the clan chieftanship.

There is a fascinating article here about the fate of Buchanan’s collections, and of the botanical paintings that he had commissioned to help with taxonomy. He was clearly a man of great energy and enthusiasm, but regularly frustrated that his lords and masters at the EIC did not appreciate the importance of his work. (The Linnean Society has some of the paintings.)

Meanwhile, what does ‘bholua’ mean? It seem to be an attempted transcription of the Nepalese name of the plant, baruwa. (In Tibet, it is apparently called chu chu.) It has an economic use, the clue being in the vernacular English name, ‘Nepalese paper plant’. The inner bark is used to make a strong and long-lasting paper called lokta, which is resistant to insect attack. (Not unlike the cork oak, which is stripped from the outside and regrows, the paper plant has to be cut back almost to the ground for harvesting, but re-sprouts, and takes about six years to re-grow to harvesting size.) The fibre can also be used to make rope, and – although all parts of the plant are poisonous – the bark and roots are used in traditional Nepalese medicine to treat fevers. Don’t try this at home; but do revel in the beautiful sight and equally beautiful scent of Daphne bholua – guaranteed to raise the spirits, however dark and gloomy the day.

Caroline

Pingback: 2020 in the Research Plots | Professor Hedgehog's Journal