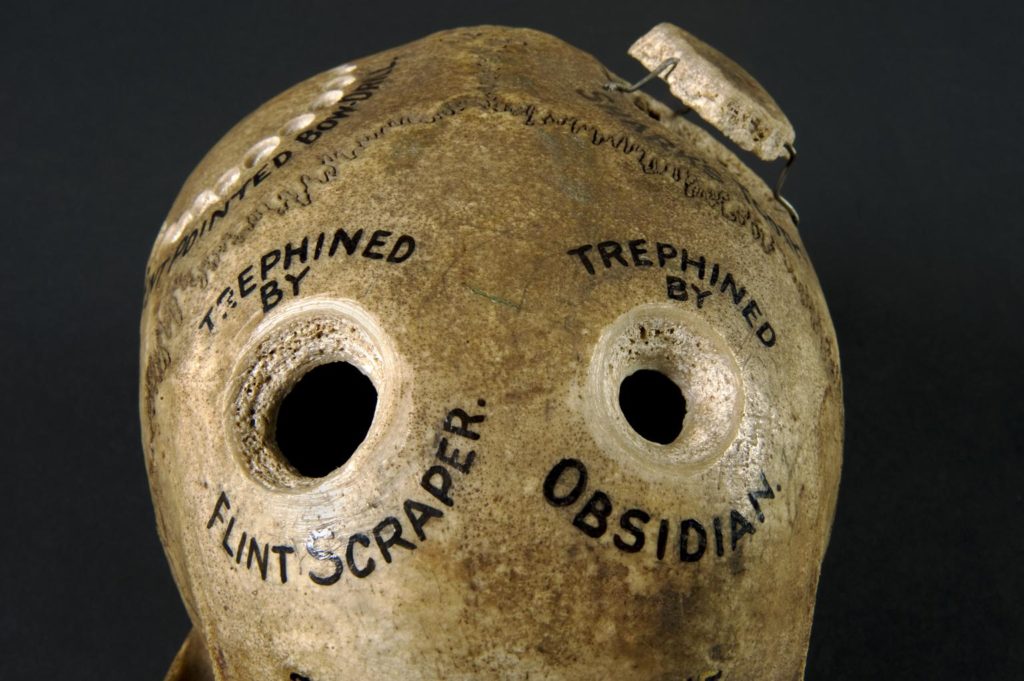

Human skull illustrating different methods of trephination owned by Dr. T. Wilson Parry, skull of Guanche, Canary Islands, 1871-1930 (approx). Credit: Science Museum, London. CC BY

Using images from the Science Museum and Wellcome Collection we explore the neolithic practice of trepanation

Archaeologists might not be able to agree on the reason why our ancestors made holes in their skulls, but what they can agree on is that humans on every continent have done it at some point in history, suggesting the seemingly-bizarre practice developed independently across multiple civilizations.

To date, thousands of skulls with trepanation holes have been unearthed at archaeological sites around the world.

more like this

Trepanation, also known as trepanning, trephining or trephination, involves creating a hole in the skull of a living person to expose the brain’s outer membrane and allowing the skin to heal over it.

The earliest skull bearing marks of trepanation dates to approximately 7,000 years ago, making it the oldest surgical procedure for which we have evidence.

‘Piece of skull showing a trephination experiment using a sha’. Credit: Science Museum, London. CC BY

Human skull illustrating different methods of trephination owned by Dr. T. Wilson Parry, skull of Guanche, Canary Islands, 1871-1930 (approx). Credit: Science Museum, London. CC BY

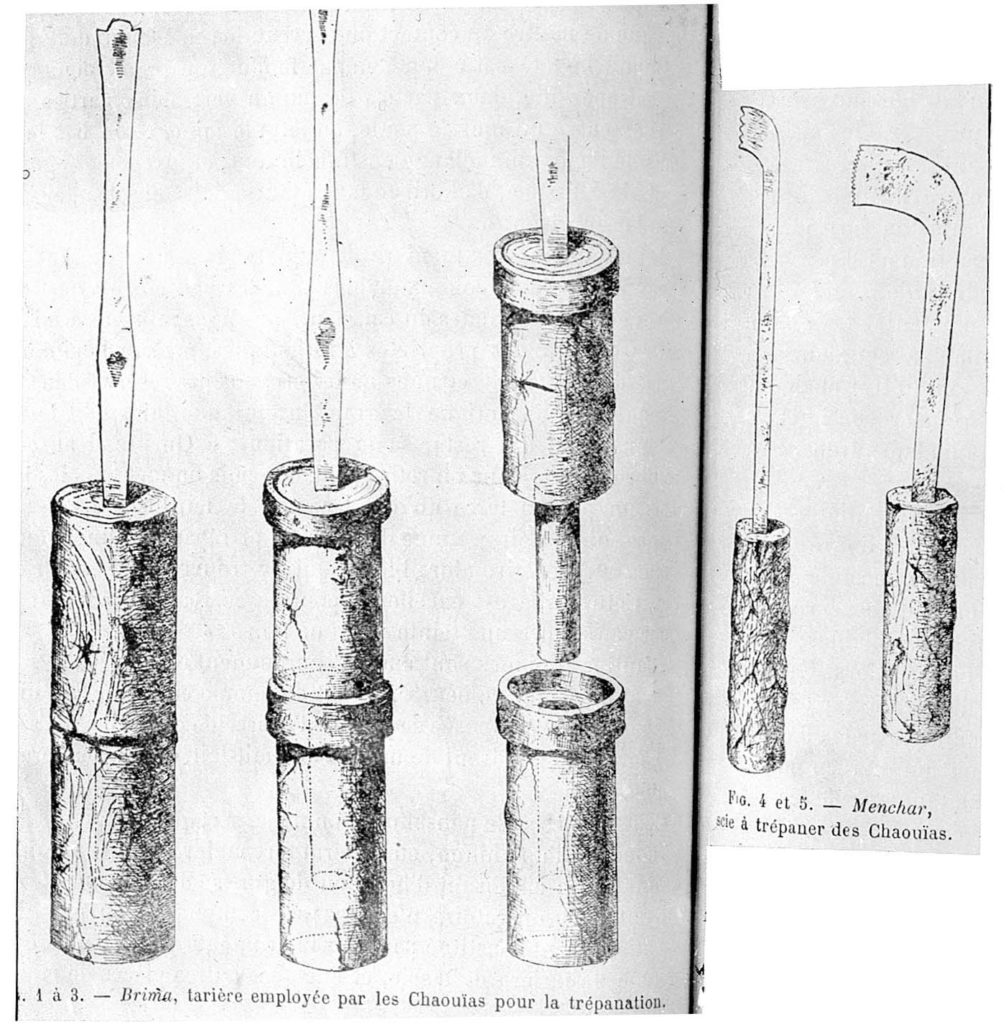

Neolithic methods of trephining by T. Wilson Parry, from the slide collection of T. Wilson Parry, No. 3977. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

British surgeon Dr Thomas Wilson Parry (1866 – 1945) was fascinated with trepanation, particularly the methods and tools used by ancient societies to perform the primitive surgery.

Throughout the early 20th century he conducted his own experiments into what implements Neolithic tribes would have employed, using whatever skulls he could lay his hands on and making his own equipment out of flint, obsidian, glass, shell and shark teeth – the results of some of which are pictured.

In 1918 he even published a humorous poem about the prehistoric custom, titled Surgery of the Stone Age: A Ballad of Neolithic Times, describing the trepanation of an epileptic man.

Parry identified four main methods of ancient trepanation: scraping; boring or drilling; the ‘push-plough’ method which involves scraping a circular furrow until you can prise a piece of skull out; and the fourth and most difficult practice in his opinion, sawing in straight lines to lift out a piece of skull, which was common in ancient Peru.

If all of this is making you feel queasy then you might ask why anyone would undergo trepanation.

Anthropological evidence from cultures which practiced the tradition up until the 19th century (such as parts of Africa and Polynesia) suggests it was used to treat an array of neurological and physiological conditions, from the aforementioned epilepsy to migraines and skull fractures.

‘Primitive surgical instruments used by the Chaoulas, from the slide collection of T. Wilson Parry, No. 3978’ . Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

‘Piece of skull used in a trephination experiment with an obsidian’ by Science Museum, London. Credit: Science Museum, London. CC BY

It is however, impossible to say for certain why ancient peoples would have performed this procedure, which – from the evidence of healing found on unearthed trepanned skulls – had a fairly high survival rate.

Some archaeologists believe it may have been used in rituals to allow the passage of spirits into or out of the body, perhaps as a cure for demonic possession or as part of an initiation rite, and it’s this supposed effect of engendering an altered state that more recent trepanners (yes, really) were searching for.

As unlikely as it seems, trepanation enjoyed a brief modern-day renaissance in the 1960s and early 70s when advocates like Bart Huges, Joey Mellen and Amanda Feilding championed it as a means to heighten consciousness.

“his favourite tool for boring holes into skulls was his hafted shark’s tooth”

The theory went that it increased blood flow in the cranium and allowed more room for the brain to swell and subside with the heartbeat, the way it does in infants before their skull bones knit together. This, they claimed, returned you to a state of childlike perception and higher consciousness.

While their hypothesis is totally unsubstantiated by science, recent research by Russian neurophysiologist Yuri Moskalenko (in collaboration with Feilding’s Beckley Foundation) has shown trepanation could potentially have a positive effect on patients with Alzheimer’s by increasing blood flow to the brain.

As for Parry’s investigations, he recorded that the average time it took him to perform a trepanation by the scraping method on a fresh adult skull was half an hour, although one record shows he managed it in a mere 13 and a half minutes using a “large and robust shell.”

And after all his experimentation he eventually concluded his favourite tool for boring holes into skulls was his hafted shark’s tooth – just the right combination of sharpness and strength to pierce a human head.

Explore the collections of the Science Museum at collection.sciencemuseum.org.uk

Explore the Wellcome Collection’s historical images at wellcomecollection.org/works

venue

Science Museum

London, Greater London

Where else can you find life-changing objects from Stephenson’s Rocket to the Apollo 10 command module, visit award winning exhibitions, take in a science show, catch an immersive 3D movie, enjoy the thrills of a special effects simulator, introduce children to science with fun, hands-on interactives and encounter the past,…

venue

Wellcome Collection

London, Greater London

A free museum and library exploring health and human experience. Located at 183 Euston Road, London, it explores the connections between medicine, life and art in the past, present and future. The venue offers visitors contemporary and historic exhibitions and collections, lively public events, the world-renowned Wellcome Library, a café,…

I think it may have been a cure for headaches. Many a time when I’ve had a bad headache I’ve felt that I needed to let the “pressure” out somehow. It would probably work with headaches that are caused by too-tight muscles over the skull – with trepanning the muscle would also be released.

But I think you would end up with a bigger headache than you started with.