Have you ever heard about Alexander Von Humboldt ? If his name doesn’t ring a bell, you might have come across one of his beautiful landscape diagrams. They usually picture a whole ecosystem along with its scientific data with a great sense of visual synthesis.

« Environmentalists, ecologists and nature writers today remain firmly rooted in Humboldt’s vision – although many have never heard of him. Nonetheless, Humboldt is their founding father. » – The Invention of Nature, Andrea Wulf

Born in 1769 (dead in 1859), Humboldt is the forgotten father of the ecological and environmental movement. The Invention of Nature is a gripping book recounting the incredible life of this XIXth century naturalist. Humboldt was a fearless explorer driven by a visionary conception of nature. He was also the most famous and influential scientist of his time.

A life of exploration

As a young man, he was very inspired by Georg Forster, the naturalist who embarked with the Captain Cook for his second expedition around the globe. Humboldt became quickly bored with his work as mine assessor. He said: « the only profession that combines science, emotion and adventure is that of an explorer naturalist. »

At the age of 30, he left Europe in 1799 with the French botanist Aimé Bonpland to go to Central and South America. The king of Spain had granted the two scientists a special authorization to explore the interior of the continent.

« Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland at the foot of the Chimborazo volcano », painting by Friedrich Georg Weitsch, 1806

« Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland at the foot of the Chimborazo volcano », painting by Friedrich Georg Weitsch, 1806

From amazon jungles to Andes’ summits, the duo traveled across Latin America for 5 years. They gathered observations and plant specimen while they were climbing volcanoes and paddling in white water. Humboldt totally immersed himself in this new environment, diving into a whole new sensory experience. In 1802 he tried to climb the Chimborazo volcano in Ecuador. He didn’t manage to reach the summit, but when he arrived at more than 20.000 feet high, he held the altitude record of his time.

Heavily equipped with timers, barometers, thermometers, telescopes, sextants, compasses, magnetometers, Humboldt and Bonpland described, drew and measured everything they encountered. Exotic plants, local people, history facts, geology, and even the different shades of blue in the sky. They used a cyanometer, a graduated tool invented by Humboldt to measure the blueness of the sky color.

Carrying their precious equipments and their ever growing naturalist collection, Humboldt and Bonpland travelled more than 10.000 miles by feet. Their boxes and jars filled with dried plants, seeds, insects, seashells or geological specimens had to be conveyed with mules or canoes.

Humboldt came back to Paris in 1804, and was greeted as a hero. His boxes were full of notebooks, with hundreds of sketches, several thousands of observations on astronomy and geology, and more than 60.000 botanical specimens. He brought back not less than 6.000 different species of plants ! One third had never been studied, or even seen before in Europe.

This expedition shaped Humboldt’s world vision for ever. It also made him incredibly famous. If Christopher Columbus discovered the geographic part of America, Humboldt was the one who discovered it scientifically.

Arts & Sciences

« From my earliest days I was excited by studying nature, and was sensitive to the wild beauty of a landscape pristling with mountains and covered in forests. » – Alexander Von Humboldt, Personal Narrative of a Journey to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent

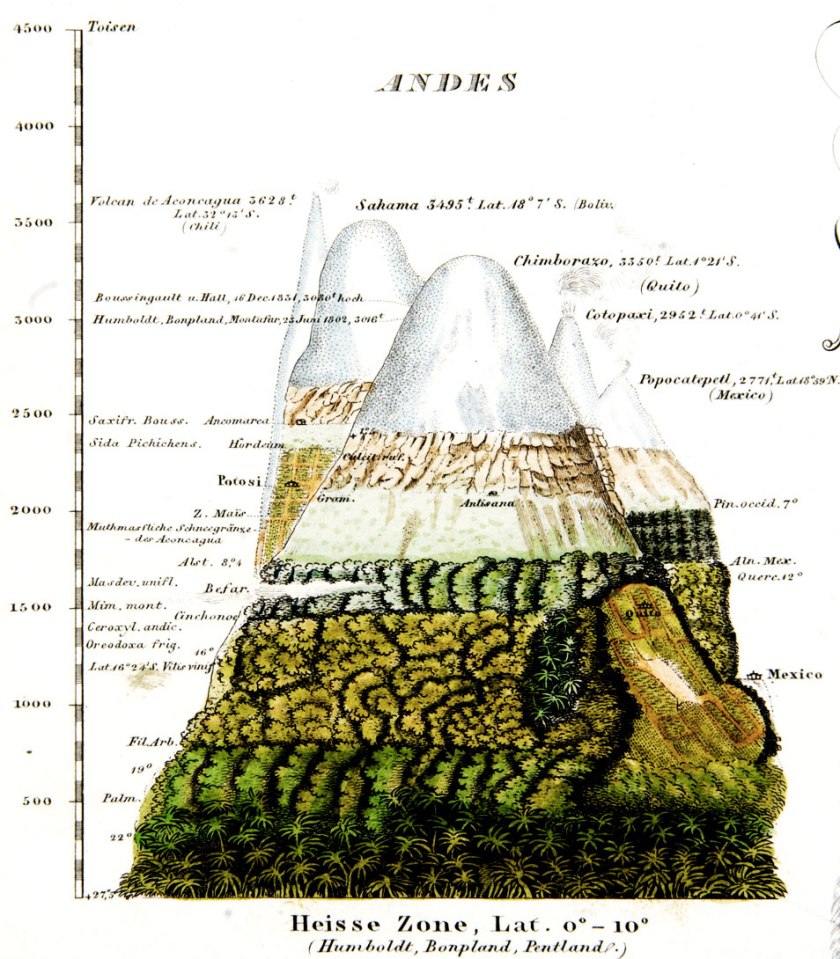

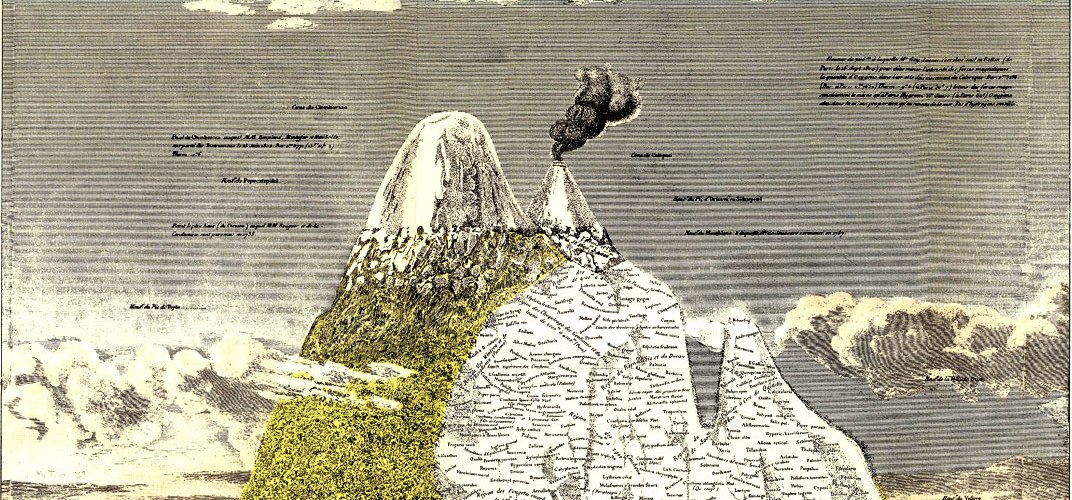

Alexander Von Humboldt, Chimborazo Volcano profile, 1829

Alexander Von Humboldt, Chimborazo Volcano profile, 1829

Humboldt was born in a healthy Prussian family. He studied many scientific disciplines, and used each of them to understand the continent he was discovering. His expedition was a way to put his academic knowledge into practice. His goal was to describe the phenomena around him in the most accurate way possible. He was at the same time a physician, a geographer, a historian, an astronomer, an ethnologist, a climatologist and a volcanologist.

At a time when scientific disciplines were hardening into tightly fenced fields, Humboldt was one of the last polymath. Scientific knowledge was becoming more and more specialized, but he wanted to study nature in a holistic way. Obsessed with the precision of his measurements, he also let his intuition and imagination guide his research. He was both collecting scientific data and writing poetic narratives. He wanted to stress on the wholeness of nature. Explaining the complex universal interrelations, he embarked his readers into a unique sensory experience. Data collected in his notebooks were accompanied by various historical, political or artistic facts.

His style was unique and appealing to a wide audience. He used a very simple and non-scientific language, pairing geology with landscape painting. During the lectures he gave, he would take the public into a kaleidoscopic and epic journey: through volcanoes and fossils, aurora borealis and magnetic fields, tropical flowers and human migrations.

Dwelling on his field notes and drawings, he published many books when he came back in Europe. Most of them quickly became very popular: Essay on the Geography of Plants, 1805 ; Views of Nature, 1850 ; Cosmos, 1847-1859, etc. The lectures he gave were always sold-out and people would come from all over the world to listen to his adventures and discoveries.

His views on landscapes

« Comparative Chart of World Mountains and Rivers », Darton and Gardner, 1823 – English printer specialized in maps, children’s books and educational publications.

« Comparative Chart of World Mountains and Rivers », Darton and Gardner, 1823 – English printer specialized in maps, children’s books and educational publications.

In order to show a synthetic vision of the different data he collected on a specific landscape, he created the « Naturgemälde » (or « Nature Paintings »). Humboldt clearly owed his view of nature as an interlocking whole to Goethe who defined nature as: « Every one thing exists for the sake of all things and all for the sake of one. » For Goethe and Humboldt, nature was unity, despite its seeming diversity. Humboldt’s Naturgemälde were a ground-breaking type of map, allowing the viewer to understand at one glance a web of intricate connections.

« A microcosm on one page. »

The Chimborazo Volcano’s Naturgemälde is a cross section showing the repartition of the different plants according to their altitude. On both sides of the mountain’s drawing, columns of numbers detail the temperature, gravity, humidity and sky whiteness. Those Naturgemälde helped him develop his Essay on the Geography of Plants, in which he studied the relationship between plant distribution and topography. His theory was based on putting the plants back into their three-dimensional context, and paying attention to the way their groups transformed under certain climatic influences.

Humboldt was passionate about discovering the relationships between things. To him, studying dried specimens in a herbarium -even if essential- was not sufficient at all to understand the complexity of plant geography. He was trying to unveil the connections by which all plants are bound together: the lands they are found and the atmospheric conditions they live in. He wanted to understand how these groupings change under the influence of altitude, climate and topography.

This totally new way of studying landscapes took into account the location, the climate and the soil.

Humboldt said: « Rather than discovering new, isolated facts I preferred linking already known ones together. The discovery of a new species seemed to me far less interesting than an observation on the geographical relations of plants, or the migration of social plants, and the heights that different plants reach on the peaks of the cordilleras. »

His graphic avant-garde

The variety of the scientific content pictured on the Naturgemälde, and its simplicity, was unprecedented. They were magnificent tableaux which illustrated the narrative of his incredible travelogue. That’s because Humboldt wanted to both educate and entertain.

Those new maps shocked the scientific world, who had never seen things like this before. Humboldt’s books being published in many languages, those images were quickly known by an international audience. They seduced non-scientific people and perpetuated the science vulgarization process, as did the images from the Encyclopédie by Diderot & D’Alembert a few years before.

Long before Google map, Instagram, 3D programs or nature documentaries, Humboldt introduced the general public to science through those appealing educational visuals.

Naturgemäldes were able to turn a complex set of data into a clear and precise map. We could look at them as ancestors of what today is « data vizualisation. » The images created by Humboldt combined the power of synthesis with visual attraction. He knew, as he told a friend, « people love to see.«

In 1817, Humboldt published an essay about climate. He wanted to do something out of the never-ending lists of numbers that meteorology was about at that time. This led him to develop a completely new map of the world figuring lines that he called « isotherms. » They represented the main air masses along the globe, and gave a global image of the different climatic zones on the planet.

Isothermal map of the world using Humboldt’s data by William Channing Woodbridge

Isothermal map of the world using Humboldt’s data by William Channing Woodbridge

He created the isotherms, those curved lines around the globe that we learned how to read with TV weather forecast.

An early influencer

Humboldt didn’t have Twitter or emails, but he was hyperactive and even started a scientific social network. In Europe, he was a beacon to which people and information would arrive. He would then spread out that information and people to other parts of the globe. He sponsored the expeditions of young scientists from all nationalities and all disciplines -often with his own money. Many French, German and Scandinavian botanists benefited from his generosity and personal encouragement. He was always talking with other scientists, both physically and virtually. He wrote thousands of letters (a total of more than 30.000!) to share his discoveries and learn about other people’s research.

Alexander Von Humboldt in his study room in Berlin

Alexander Von Humboldt in his study room in Berlin

He believed that scientific information had to be shared. And that open-source knowledge had the power to transform sciences. Humboldt only travelled a little in between Paris and Berlin after his Latin America journey. But he would ask the naturalists on fields and his colleagues abroad to send him data and information. This material was organized through a complex system of thematic boxes. Each piece of information was pulled out when needed to nourish his new books.

Choosing to live in Paris, he had to publish his first books in French. At that time and since the French Revolution, science and arts had way more freedom in this city than any other European ones. Humboldt spoke fluently in German, French, Spanish and English, he could then spread his research even more internationally. At the end of the XIXth century, his book Cosmos, A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe had already been published in more than 15 languages !

« Everybody learned from him: farmers and craftsmen, schoolboys and teachers, artists and musicians, scientists and politicians » – The Invention of Nature, Andrea Wulf

Humboldt’s influence can be tracked among many famous people of his time. His holistic approach inspired the science world: the astronomer François Arago, the anatomist Georges Cuvier, the chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, and even the young naturalist Charles Darwin, who decided to embark on the Beagle in order to follow Humboldt’s steps. He even read Humboldt’s books many times and with great enthusiasm during his trip.

In the literary world, Humboldt was admired by Balzac, Hugo, Chateaubriand, Flaubert, Emerson and Thoreau. Those writers loved how the naturalist managed to combine scientific descriptions with immersive poetic narratives.

Chimborazo volcano

Chimborazo volcano

Humboldt was a great defender of human rights. He was one of the first to publicly criticize imperialism, racism and slavery. He questioned the way Spain managed its colonies and exploited the natural and human resources there. He met with Thomas Jefferson, president of the United States, to discuss topics such as natural history and ethnography. But even more, Jefferson was eager to hear the treasures of information Humboldt had gathered about Latin America’s politics and ecology.

In Paris, Humboldt became friends with Simon Bolivar. Humboldt’s descriptions of Venezuela fed the young revolutionary’s romantic dream. His humanist position encouraged Bolivar to fight for the freedom of Spanish colonies.

Humboldt also inspired the German biologist Ernst Haeckel, who invented a new discipline called « ecology. » Ecology was the « science of the relationships of an organism with its environment », as defined by Haeckel. The book Forms of Nature depicted in a sumptuous way the different living organisms. Haeckel’s drawings emphasized on the geometric patterns hidden in nature’s shapes. It was a tribute to link art with biology. This book was a great popular success, as Humboldt’s were.

Ernst Haeckel, « Forms of Nature », the 84th plate depicting diatoms

Ernst Haeckel, « Forms of Nature », the 84th plate depicting diatoms

Environmental activist and botanist lover, John Muir was another of Humboldt’s followers. Muir believed in the university of wildlife, more than in going to school. He travelled by foot across the USA. He also had read Humboldt and kept dreaming about an epic journey throughout South America. When he finally stopped his journey in California, because of health problems, he fell in love with Yosemite Valley. He started studying in detail this region while picking up small jobs in ranch, sawmills and as a shepherd. Muir was worried that human activities will damage the Yosemite ecosystem for ever. He was convinced that this valley needed to be protected and classified as a National Park. He created the Sierra Club, a non-profit organization aimed at protecting wilderness and promoting a more sustainable use of resources and ecosystems.

No planet B

In Humboldt’s view, the general equilibrium on Earth is the result of an infinity of mechanical forces and chemical attractions balancing each other out. He described nature as a web of life where everything was connected. Seeing our planet as a living organism in perpetual evolution, he pre–dated James Lovelock’s Gaia Theory by more than a century. He understood early on that if the Earth was a single interconnected organism, it could be catastrophically damaged by human destructive actions.

Humboldt listed the three ways in which the human species was affecting climate. He named: deforestation, ruthless irrigation and the great masses of steam and gas produced in the industrial centers. No one but Humboldt had looked at the relationship between humankind and nature like this before.

Following Humboldt’s ideas, Georges Perkins Marsh published in 1864 his book Man and Nature : Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. He originally wanted to call the book « Man the Disturber of Nature’s Harmonies » – a title he was dissuaded from by his publisher who felt it would damage sales…

In this book, Marsh insisted (as Humboldt did before him) on the fact that all nature is linked together by invisible bonds. Page after page, Marsh talked about the evils of deforestation. He explained how forests protected the soil and natural springs. Once the forest was gone, the soil lay bare against winds, sun and rain. The earth would no longer be a sponge but a dust heap. As the soil was washed off, all goodness disappeared. The more forests disappear, the less biodiversity was found and the more climatic change would occur.

At the time the US became the fourth largest manufacturing country in the world, Marsh takes Humboldt’s early warning about deforestation to its full conclusion. Man and Nature told a « story of destruction and avarice, of extinction and exploitation, as well as of depleted soil and torrential floods. »

Learning from Humboldt

« It feels as if we’ve come full circle. Maybe now is the moment for us and for the environmental movement to reclaim Alexander von Humboldt as our hero. » – The Invention of Nature, Andrea Wulf

Contemporary thinkers in the ecology and Anthropocene field (as Bruno Latour in France) are Humboldt’s successors. Here are a few lessons this incredible naturalist left for us, and that we should remember:

- Focus on field research and take advantage of full immersion (physical and emotional) to adopt a new way of seeing a subject.

- Do not let knowledge be classified into predefined boxes.

- Share the scientific data and field research results in an open-source way.

- Acknowledge the power of images to educate the masses on complex scientific subjects. Use them as a tool of positive influence.

- Recognize the negative impact of industrial activities on the environment, on natural resources and on living beings. Adopt new strategies of cohabitation between humans and nature. Move from a dynamics of nature’s domination to a dynamics of cooperation with nature.

More

– The book: « The invention of nature, Alexander von Humboldt’s New World », Andrea Wulf, Vintage, 2016

Other articles about the book and the man:

-The New Yorker: « Humboldt’s Gift »

-The Ecologist: « The Invention of Nature: adventures of Alexander Humboldt, lost hero of science »

-Geographical: « The Invention of Nature »

8 réflexions sur “Humboldt – The Invention of nature”