SPECIAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, POLICY & PRACTICE

November 15, 2020 Volume 4, Issue 1 Table of Contents

Page

Editorial Board of Reviewers

3

Enhancing the Comprehension of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Teachers Share Their Experiences Gina Braun and Marie Tejero Hughes

6

Teachers as Behavior Professionals: Understanding the Experiences of Teachers as BCBAs Justin N. Coy and Jennifer L. Russell

27

An Exploratory Study of the Relationship between School Counselors and Special Education Teachers Marquis C. Grant

51

Special Education Law in the United States of America and the Sultanate of Oman Maryam Alakhzami and Morgan Chitiyo

62

Cultural Responsiveness in Reading Comprehension Interventions for English Learners with Learning Disabilities Sara Jozwik, Yojanna Cuenca-Carlino, Miranda Lin, April Mustian, and Stacey Hardin

74

Special Education Providers: Survey of Caseload Numbers, HQT, and Instructional Settings Patricia Prunty

95

1

Supporting Campus Navigation Knowledge via 3D Mapping Instruction among College Students with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Sharon Richter, Heather Hagan, and Cheryl Morgan

107

How are Functional Behavior Assessments (FBA) and Behavior Intervention Plans (BIP) Conducted in Public Schools? A Survey of Educators Andria Young and Terrisa Cortines

116

Evaluation and Practices of Mobile Applications as an Assistive Technology for Students with Dyslexia: A Systematic Review Nicole Bell and Julia VanderMolen

128

Behavior Management in the Early Childhood Classroom: Preschool Teachers’ Self-Reported Usage Prevention and Intervention Strategies Marla J. Lohmann

143

Author Guidelines

152

Publishing Process

153

Copyright and Reprint Rights

154

2

Editorial Board of Reviewers All members of the Hofstra University Special Education Department will sit on the Editorial Board for the SPECIAL EDUCATION RESEARCH, POLICY & PRACTICE. Each of the faculty will reach out to professionals in the field whom he/she knows to start the process of building a list of peer reviewers for specific types of articles. Reviewer selection is critical to the publication process, and we will base our choice on many factors, including expertise, reputation, specific recommendations and previous experience of a reviewer. Editor George Giuliani, J.D., Psy.D., Hofstra University Hofstra University Special Education Faculty Elfreda Blue, Ph.D. Stephen Hernandez, Ed.D. Gloria Lodato Wilson, Ph.D. Mary McDonald, Ph.D., BCBA Darra Pace, Ed.D. Diane Schwartz, Ed.D. Editorial Board Mohammed Alzyoudi, Ph.D., UAEU Faith Andreasen, Ph.D., Morningside College Vance L. Austin, Ph.D., Manhattanville College Amy Balin, Ph.D., Simmons College Dana Battaglia, Ph.D., Adelphi University Brooke Blanks, Ph.D., Radford University Kathleen Boothe, Ph.D., Southeastern Oklahoma State University Nicholas Catania, Ph.D. Candidate, University of South Florida Lindsey A. Chapman, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Miami Morgan Chitiyo, Ph.D., Duquesne University Jonathan Chitiyo, Ph.D., University of Pittsburgh at Bradford Heidi Cornell, Ph.D., Wichita State University Lesley Craig-Unkefer, Ed.D., Middle Tennessee State University Amy Davies Lackey, Ph.D., BCBA-D Josh Del Viscovo, MS, BCSE, Northcentral University Janet R. DeSimone, Ed.D., Lehman College, The City University of New York Lisa Dille, Ed.D., BCBA, Georgian Court University William Dorfman, B.A. (MA in progress), Florida International University Brandi Eley, Ph.D. Tracey Falardeau, M.A., Oklahoma State Department of Education Danielle Feeney, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Lisa Fleisher, Ph.D., New York University

3

Neil O. Friesland, Ed.D., MidAmerica Nazarene University Theresa Garfield Dorel, Ed.D., Texas A&M University San Antonio Leigh Gates, Ed.D., University of North Carolina Wilmington Sean Green, Ph.D. Deborah W. Hartman, M.S., Cedar Crest College Shawnna Helf, Ph.D., Winthrop University Nicole Irish, Ed.D., University of the Cumberlands Randa G. Keeley, Ph.D., New Mexico State University Hyun Uk Kim, Ph.D., Simmons College Louisa Kramer-Vida, Ed.D., Long Island University Nai-Cheng Kuo, PhD., BCBA, Augusta University RenÊe E. Lastrapes, Ph.D., University of Houston-Clear Lake Debra Leach, Ed.D., BCBA, Winthrop University Marla J. Lohmann, Ph.D., Colorado Christian University Mary Lombardo-Graves, Ed.D., University of Evansville Pamela E. Lowry, Ed.D., Georgian Court University Matthew D. Lucas, Ed.D., Longwood University Jay R. Lucker, Ed.D., Howard University Jennifer N. Mahdavi, Ph.D., BCBA-D, Sonoma State University Alyson Martin, Ed.D., Fairfield University Marcia Montague, Ph.D., Texas A&M University Chelsea T. Morris, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Miami Gena Nelson, Ph.D. Candidate, American Institutes for Research Lawrence Nhemachena, MSc, Universidade Catolica de Mozambique Maria B. Peterson Ahmad, Ph.D., Western Oregon University Christine Powell. Ed.D., California Lutheran University Deborah Reed, Ph.D., University of Iowa Ken Reimer, Ph.D., University of Winnipeg Dana Reinecke, Ph.D., Long Island University-C.W. Post Denise Rich-Gross, Ph.D., University of Akron Benjamin Riden, ABD - Ph.D., Penn State Mary Runo, Ph.D., Kenyatta University Emily Rutherford, Ed.D., Midwestern State University Carrie Semmelroth, Ed.D.., Boise State University Pamela Schmidt, M.S., Freeport High School Special Education Department Edward Schultz, Ph.D., Midwestern State University Mustafa Serdar KOKSAL, Ph.D., Inonu University Emily R. Shamash, Ed.D., Teachers College, Columbia University Christopher E. Smith, PhD, BCBA-D, Long Island University Gregory W. Smith. Ph.D., University of Southern Mississippi Emily Sobeck, Ph.D., Franciscan University Ernest Solar, Ph.D., Mount St. Mary’s University Gretchen L. Stewart , Ph.D. Candidate, University of South Florida Roben Taylor, Ed.D., Dalton State College

4

Jessie Sue Thacker-King, Arkansas State University Julia VanderMolen, Ph.D., Grand Valley State University Cindy Widner, Ed.D. Candidate, Carson Newman University Kathleen G. Winterman, Ed.D., Xavier University Sara B. Woolf, Ed.D., Queens College, City University of New York Perry A. Zirkel, J.D., Ph.D., Lehigh University

5

Enhancing the Comprehension of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Teachers Share Their Experiences Gina Braun, Ph.D. Rockford University Marie Tejero Hughes, Ph.D. University of Illinois at Chicago Abstract Providing literacy instruction to students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be challenging due to the students' wide range of unique learning needs. While their needs vary, many students with ASD often have difficulty building a deep understanding of complex texts. In this study, special education teachers were interviewed to determine their perspectives and experiences, providing literacy instruction to students with ASD. Multiple findings emerged from the conversations with the special education teachers, including the instructional practices used during comprehension instruction, specific instructional considerations for students with ASD, and challenges to providing comprehension instruction to this population. The information gained from these teachers can guide future endeavors in designing preparation programs to meet the needs of teachers providing literacy instruction to students with ASD. Enhancing the comprehension of students with autism spectrum disorder: Teachers share their experiences Over the last 20 years, there has been a significant increase in the number of students receiving services for autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which in turn increases the demand for educators to identify teaching strategies that lead to successful literacy outcomes for these students (Brock, Huber, Carter, Juarez, & Warren, 2014). Today 1 in 59 children in the United States (US) are diagnosed with ASD, compared to 1 in 150 two decades ago (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). This rapid increase in children with ASD has undoubtedly transferred to the population of students receiving services for ASD in schools. Approximately 13% of students in US public schools receive services for their disabilities under IDEA, of these students, nearly 10% are identified with ASD (United Stated Department of Education, 2018). Therefore, there is a wide- range of diverse student needs, including social, emotional, behavioral, and academic challenges that educators need to be prepared to address. Understanding Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder Autism was initially defined by Leo Kanner, a US psychiatrist, in the 1940s. The profiles he developed emphasized that his participants tended to consist of more males than females. Socially, they preferred to play alone as opposed to with peers or their parents, and many were nonverbal past infancy and into childhood. Likewise, they seem to be oblivious to the world around them. Behaviorally, the children engaged in repetitive behaviors and had frequent outbursts when their routines were disrupted (Kanner, 1943). Since Kanner's first description of autism, definitions of ASD have evolved helping to construct both medical and social models. 6

While the original medical models utilized a spectrum on which children either labeled "high incidence" or Asperger's Syndrome, and "low-incidence," the model has since evolved. Today the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders - 5 (DSM-5; APA, 2013) indicates that children with ASD may display difficulty with communication and interactions, may have restricted interests and repetitive behaviors, and might have a difficult time successfully integrating into school, work, and other areas of life (National Institute of Mental Health, 2015). Specifically, children with ASD show little interest in making friends, prefer their own company, fail to show interest in imitating the behaviors of others, often avoid eye contact, lack imagination, and typically do not empathize with others. Also, children with ASD often display aggressive or self-injurious behaviors (Kluth & Chandler-Olcott, 2008). Though medical professionals and educators utilize the general medical definitions and profiles, the autism spectrum is vast, and individuals that fall on the spectrum have a wide variety of unique needs (Secan & Mason, 2013), making no two students alike. Therefore, recognizing the social model of ASD helps educators understand how best to adapt literacy instructional supports and strategies for instructing students with ASD. This means, going beyond the definition and considering how society has played a role in boxing-in students with these common characteristics and labeling them as having a disability rather than a neurodifferent way of being. Thus, educators need to move beyond these definitions and consider the student with ASD as a whole person who approaches the world differently (Kluth & Chandler-Olcott, 2008). Addressing the varied needs of students with ASD requires teachers to have a deeper understanding of their students' individual needs (Leblanc, Richardson, & Burns, 2009), as well as knowledge of evidence-based practices that meet their needs (Mitchell, 2007). Several reviews of the literature have examined the effects of social, communication and behavioral interventions for students with ASD in schools (e.g., Bellini, Peters, Benner, & Hopf, 2007; Shukla-Mehta, Miller, & Callahan, 2010). Research has shown that practices such as video-modeling (Wang & Spillane, 2009) and including general education peers in social skills training (Hughes et al., 2011) can lead to positive learning outcomes for students with ASD. Other strategies, such as applied behavioral analysis (ABA), have been widely researched and have also shown to be successful for students with ASD (Pine, Luby, Abbacchi, & Constantino, 2006). Overall, the research strongly supports the use of evidence-based practices in and out of schools to support the social, emotional, and behavioral needs of students. While not as abundant as social, emotional, and behavioral supports, researchers have examined some characteristics that explain the common academic needs of students with ASD (e.g., Fleury et al., 2014; Keen, Webster, & Ridley, 2016; McIntyre et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2015). Research shows that many students with ASD struggle with communication, tend to show challenges with auditory processing, focus on processing minute details, struggle with understanding the perspectives of others and determining bigger picture items, and have deficits in executive functioning and memory (Fleury et al., 2014). Furthermore, the most common characteristics that emerge in the literature when examining the academic performance of students with ASD is their difficulty in literacy (Brown, Oram-Cardy, & Johnson, 2012; Nation, Clark, Wright, & Williams, 2006). Although many students with ASD have strong decoding skills (Brown et al., 2012), they tend to struggle with comprehension (Nation et al., 2006; Ricketts, Jones, Happe, & Charman, 7

2013). A possible reason for this is partly due to challenges that derive from their disability, such as struggling to understand others point of view (Brown et al., 2012), an essential skill in reading comprehension. Comprehension and Autism Spectrum Disorder Researchers have identified several characteristics related to literacy, many students with ASD exhibit. In particular, research shows that although many students with ASD tend to demonstrate strengths in reading accuracy and word recall, they often struggle to deeply understand complex texts (Nation et al., 2006), and they tend to have more difficulty with fictional texts as opposed to expository texts (Gately, 2008). Fictional texts typically require students to use inferential thinking, decipher the meaning of figurative language, and understand other points of view, such as the authors’ purpose or characters’ perspectives (Williamson, Carnahan, & Jacobs, 2012). While students with ASD often show more difficulties in comprehending fictional texts, they are challenged in understanding most expository texts that require them to access their background knowledge (Williamson et al., 2012). Although there tend to be similar characteristics across this population of students, due to their varied cognitive abilities, there are diverse comprehension profiles for each student which requires teachers to provide various instructional supports for each student (Nation et al., 2006). Though the research on comprehension instruction specifically focused on the needs of students with ASD is not as robust as other areas, several reviews have examined the previously completed work relative to strategies for improving comprehension (e.g., Chiang & Lin, 2007; El Zein, Solis, Vaughn, & McCulley, 2014; Finnegan & Mazine, 2016). Amongst these reviews the strategies that show consistent positive outcomes for students with ASD are the use of direct and explicit instruction (Flores & Ganz, 2007; 2009); cooperative learning (Kamps, Barbetta, Leonard, & Delquadri, 1994; Kamps, Leonard, Potucek, & Garrison-Harrell, 1995); and graphic organizers (Stringfield, Luscre, & Gast, 2011). Additionally, students with ASD show success in comprehension when texts are pairs with visual supports (Saldana & Frith, 2007). Students also demonstrate positive outcomes in comprehension when anaphoric cueing is used (O'Conner & Klein, 2004). Furthermore, when reciprocal questioning strategies are included during comprehension instruction, students with ASD tend to have more positive outcomes (Whalon & Hanline, 2008). While the reviews of literature demonstrate that some of the comprehension research for students with ASD follow a prescribed intervention (e.g., Flores & Ganz, 2009), many other studies do not adhere to one prescribed program, instead they are "packaged" providing multiple evidence-based strategies to support the unique styles of the learners (e.g., El Zein et al., 2014; Stringfield et al., 2011). Although there is promising research emerging comprehension instruction for students with ASD, the research provides little information on how teachers utilize these practices and adapt literacy instruction in schools to support the unique needs of students with ASD to enhance their comprehension (Huber & Carter, 2016). Purpose of Study As the demand increases for providing all students with access to the general education curriculum, there is a pressing need to prepare educators to teach students with ASD in all academic areas (Loiacono & Valenti, 2010). This is especially true because teachers have indicated that they are not very confident in their ability to implement evidence-based practices and address critical issues for students with ASD (Brock et al., 2014). Though research 8

demonstrates that evidence-based practices increase positive outcomes for students with ASD, there remains evidence that there continues to be a significant gap in research and practice (Cook & Odom, 2013). Likewise, many teachers do not know how best to meet the needs of their students with ASD, and there is lack of research examining the strategies that teachers are using to support their students' literacy needs (Brock et al., 2014). Thus, the purpose of this study was to engage in conversation with special educators who have experience teaching literacy to students with ASD to obtain a better sense of what is working and what is not. We were interested in answering the following questions: 1) What instructional practices do special education teachers use when teaching comprehension to students with disabilities in grades 4-8?; 2) What do special education teachers indicate are effective strategies, practices, and tools for teaching comprehension to students with ASD?; and 3) Do special education teachers perceive any specific concerns or challenges in teaching comprehension to students with ASD? Methods Participants Twelve certified special education teachers who provided literacy instruction for at least one year to students in grades 4-8 with ASD, participated in the study. All teachers taught in schools located in a large Midwest metropolis area. All but one of the teachers had a master’s degree in special education. The average years of teaching experience was 5.8 years (range of 2-13 years), and the average years of teaching students with ASD was 4.8 years (range of 2-13). For this study, all the teachers had to have recently taught in grades 4-8 and where asked to specifically discuss their literacy instruction experiences involving students with ASD in these grade levels (seven of the teachers taught in grades 4-5, three teachers instructed grades 3-8 and two teachers taught grades 6-8. Instrument Interview. Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with the teachers to gauge their perspectives and experiences teaching literacy to students with ASD. During the interview, the teachers were asked to consider their instructional practices for their students with ASD in grades 4 to 8. Because the range of functionality for students with ASD varies, we asked the teachers to focus their responses on the students they teach or have taught that were considered the high-functioning, meaning that the students are verbal (speaks at least 2-3 word phrases) and that their instructional reading level was no more than three grade levels below their current grade. The interview consisted of main questions with probes to help guide the conversation (see Appendix A). The questions for the interview were developed based on the researchers' experiences working with students with ASD, as well as coaching and preparing special educators. Before data collection, the researcher pre-viewed the interview questions with special education teachers and graduate students who have experience working with students with ASD. The researcher then refined the questions based on feedback. The first four questions unpacked the teachers' general knowledge and experience teaching comprehension. The teachers were prompted to consider all their students and the instructional practices used with each. The next six questions focused on the teachers' instructional practice for their students with ASD specifically discussing planning consideration, instructional strategies, and most significant 9

difficulties. The final six questions gathered information on the teachers' general background relative to teaching and educational preparation. The average length of each interview was 45 minutes. Procedures Once the Institutional Review Board approved the study, the recruitment progress began. The use of purposive sampling for the recruitment of 12 special education teachers supported a strategic focus of aligning the research questions to the narrow population of educators in this field (Patton, 2015). As a former special education teacher, the first author contacted 15 teachers in her professional network, where an established email correspondence was already in place. Of the original 15 emailed, 12 responded; however, through a more in-depth eligibility screening phone call, only eight were found eligible to participate. To expand the search for teachers, snowball sampling was implemented (Goodman, 1961) by including in the recruitment email, a statement asking for referents who fit the criteria. The email recipient could forward the email on to them, and then additional interested teachers could inquire about the study. Through this method, the first four teachers who showed interest and qualified to participate were included in the study. For an initial, descriptive study that consists of an in-depth interview, a range of 6-10 participants provides a rich description of the investigated questions (Patton, 2015); therefore the 12 teachers who consented and participated in the study provide a strong sample to examine the research questions. Interviews took place over the phone at a time that was convenient for the teachers. All the conversations were digitally recorded and transcribed. Transcriptions of the interviews were sent to the teachers for members checking, and the teachers offered no changes. Data Analysis Qualitative methods for analysis were used to analyze the interviews (Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014), which included a multi-phase process that involved coding for themes and categories (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). During the first phase of the analysis, the researcher carefully read half of the interviews, using an open coding to process to make meaning. In open coding, the researcher forms categories of information about the phenomenon being studied by segmenting data (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). Codes were constructed by the researchers utilizing academic terms aligned with the research questions (Saldana, 2015), such as discussing strategy instruction, selecting texts, and considering adaptations. Once created, the codes were combined, and common categories were determined based on identified themes emerging from the codes. Upon the development of the categories, the second phase of the analysis consisted of coding all the interviews using the common categories, and further developing subcategories amongst them. Throughout the data analysis process, the researchers engaged in analytic memoing (Charmaz, 2014) to help draw connections between the codes to further understand the perspectives and experiences of the teachers (Saldana, 2015). Results We identified three major themes from the teacher interviews, including (1) instructional practices during comprehension instruction, (2) instructional consideration for students with ASD, and (3) challenges to comprehension instruction. Below is a breakdown of the major themes. Pseudonyms have been used to discuss any information related directly to the participants in this study. 10

Instructional Practices during Comprehension Instruction Teachers were asked to describe their typical comprehension instruction to students with disabilities, not necessarily specific to students with ASD, to gain an understanding of the comprehension instruction that their students received. Four main categories emerged based on the frequency of teacher discussion in this area: established curriculum and programs; modeling and guided practice, small group instruction; and vocabulary instruction. Use of established curriculum. Each of the teachers mentioned following a literacy curriculum for teaching comprehension. Curriculums and frameworks were not only used for the whole group but small groups as well. These included more widely known programs such as Leveled Literacy Instruction, to small curriculums such as Engage NY and Wonderworks. All teachers mentioned that they followed the curriculums to help them select instructional strategies to guide the scope and sequence for the school year. While many teachers said they began their instruction using an established curriculum or program, they made significant modifications, and embedded supplemental supports to it to align to their students' needs. All the teachers stated that they enjoyed following curriculums because they not only provided a scope and sequence for teaching comprehension skills and strategies, but they also offered support in helping to align instructional content to the students' general education peers. For example, Ms. Rizzo stated: "Our district just adapted WonderWorks, which is the general education curriculum, this year, and it came with an adapted version which is awesome!" While another teacher, Ms. O’Conner, did not mention a specific curriculum, though she stated she follows a “strategy-type curriculum… that utilizes short passages and its scaffolded throughout the week.” Modeling and guided practice. All the teachers discussed their instructional strategy techniques for building their students' comprehension with all mentioning a similar framework for structuring their comprehension instruction which included modeling of a skill or strategy followed by guided practice and independent work. When discussing her framework for daily comprehension instruction, Ms. Griffin said, "So I do a reading workshop, where I will present specific reading comprehension skill with a read-aloud text. Then, practice with students ... I also do a lot of like, Think Pair Share, or conversations around it the new skill during this time." When teachers described their modeling of skills and strategies, most discussed that it was done in the context of a book excerpt or a short text, usually on or near students' grade levels. For example, Mr. Russo stated that during "whole group, every day, we do like a higher-level read aloud, one that is closer to grade level, so that way they're accessing higher ideas and vocabulary and themes." Teachers also considered a specific strategy, such as visualization or summarization, and aligned the use of the strategy with the curriculums they were using. All the teachers mentioned modeling metacognition strategies such as stopping at signified spots in the book to "think aloud" to model for the students the way they make meaning of a text. To introduce comprehension strategies, the teachers pre-planned and implemented both a metacognitive model followed by guided practice, including in-the-moment feedback. To engage in guided practice, many of the teachers mentioned they pre-plan comprehension questions around the modeled text such as- a simple call and response, or they may engage students in a partner turn and talk. Most teachers also mentioned embedding shared reading 11

during this time. To facilitate comprehension, many teachers also required the students to do some form of writing, usually through the use of a graphic organizer, as they followed along with the read aloud or shared reading of the texts. The writing typically aligned with the skill or strategy taught. Many of the teachers used this writing to help determine if students understood the skill. Though all teachers mentioned that modeling and guided practice were followed up with independent work, this work was significantly scaffolded and often supported by the teachers or a paraprofessional in the classroom in a center-like a format. Small group instruction. Teachers discussed that students needed a lot of differentiated strategies and support to utilize the higher-order thinking skills required to access complex texts. Although all teachers allowed time for independent work, many of them used this independent time to group students into small groups related to the individual needs of students to provide significant scaffolded instruction. The teachers formed small groups in a variety of ways; some teachers relied solely on district or classroom-based diagnostic assessments, while others mixed groups based on literacy skill deficits and even some considered behavioral needs amongst the students. Ms. Fernandez was adamant about the use of small groups to provide instruction that meets their students' needs: It's like you need to get them into that small group level time, where you can work with students even like one to two of them, and hone in on are their strengths or weaknesses and work from there because that's where everything happens. The teachers discussed the importance of small groups as an opportunity for students to repeat and practice what they are learning and eventually transfer to independent practice. Mr. Russo stated, "And a lot of them it's giving them strategies that we just reinforce and practice so often, so over time it becomes intuitive to them when they are reading independently." During this group time, teachers would typically provide texts for students to choose at their reading level. While this time was geared more for students to practice the skills on their own out of their instructional level books, all the teachers mentioned that they continued to provide a plethora of supports, strategies, and prompts to guide the students to work on the skills throughout their reading instruction. Ms. Roo mentioned this level of support is, "… just honestly like so second nature in special educations, it's like what does this kid need?" Vocabulary instruction. During comprehension instruction, teachers reported spending a significant amount of time on developing students’ vocabulary. Though vocabulary instruction took on slightly different forms, each of the teachers spent a specified time teaching new words to their students. Many of the teachers identified "tricky words" that would appear in the text during the teacher’s model of skills or when reading a shared text. When discussing vocabulary instruction in context, Ms. Hayes stated, "I might be reading a page in a book. We'll come across a word that is an interesting word, so a word we don't know, or we'll try to use the context clues and the pictures to figure out what the word means.” Sometimes, teachers used direct instruction strategies to intentionally teach new academic vocabularies, such as author’s purpose or summarization. Those teachers typically provided a mix of both contextual and direct instruction. Some of the teachers also taught vocabulary explicitly by giving definitions and providing visual examples, while others had students share out what they thought the meanings might be and then provided some direct instruction as needed. Other teachers identified vocabulary with similar 12

morphologies and would focus on a few prefixes or affixes and encourage students to find and use the vocabulary in context. Regardless of the strategy and context for instruction, all teachers found vocabulary instruction to be an integral part of developing students’ comprehension. Instructional Considerations for Students with ASD Teachers talked about the importance of considering the unique needs of each student with ASD and how they made adaptations to their comprehension instruction in consideration of the students need. Teachers discussed the importance of developing lessons that helped students go beyond surface-level understanding and allowed them to show their understanding of the text in a variety of ways. They also mentioned that it was not only important to consider text selection and strategy instruction but to also meet their social, emotional, and behavioral needs. Teachers also mentioned that it was key for them to develop comprehension lessons that were explicit and systematic, as Ms. McCarthy said, “as much as I could provide a systematic structure to the lessons, the more success my students had.” Going beyond explicitness. Teachers stated they expected students to go beyond the explicit meaning of a text and to provide evidence for their assertions. In her interview, Ms. Wilson summed this up perfectly, "just because your students can answer questions from a text, still doesn’t necessarily mean that they're understanding it." All teachers mentioned this is a crucial component to determining if students truly grasped the deep meaning of the text, but that going beyond the explicitness of the text was challenging for students. Teachers also discussed that it was not only about going beyond the text but that students needed to be able to use evidence from the text to explain their thinking. For example, Ms. Walsh discussed what she looks for in her students when determining if they understand the text: Basic level of comprehension is being able to retell the text. Like, you're following the plot, you're following who the characters are, and what the "events" of the text are… as we started to analyze a text, I’m determining somebody's ability to inference or somebody's ability to analyze a character's motivations with evidence to support…it shows somebody is interpreting a text rather than just something pretty concrete. They are providing a variety of modalities. All teachers mentioned that they differentiated their expectations for how students show their understanding of a text. Teachers indicated that they understood that "showing what you know" may look different for each student and that they considered different modalities for how students demonstrate their comprehension of a text. The teachers mentioned practices such as asking students for verbal and recorded responses to questions, providing students with visuals or even objects to represent their understanding, using post-it notes and a variety of graphic organizers to jot down thoughts and keep track of thinking, and providing anchor charts with common prompts and sentence stems. Some teachers stated they have students act out the story from a text, such as Mrs. McCarthy does, “I had a costume box, so whatever book we are reading we transfer into like our own reader's theater and they would act it out.” Setting students up for success. Throughout the interviews, there were commonalities that teachers mentioned as considerations for setting their students with ASD up for success. First, when considering the selection of texts, many teachers stated they would typically consider the 13

interest of the student with ASD, and even select texts with similar themes over several weeks. Mr. Russo said, "But another thing I've found with a lot of my students whom I've worked with autism is using a book series, for example, student B, loved like a particular series. So, like finding books with obviously like reoccurring characters and stuff." When discussing independent reading time, teachers provided both independent level texts as well as texts that pique interest and give the students choices. For example, Ms. Griffin said, "... the books in their reading bins always consist of like a mixture of their instructional level, and texts not on their level focused on their interests.” However, other teachers mentioned that rather than always relying on student interest to select texts, they plan to expand their students’ interests; therefore, once a text is selected, intensive planning went into pre-teaching and building background knowledge on the particular text topic to get the student excited. This could be in the form of showing videos, pictures, going on field trips such as museums, places in the community, or relating the new topics to something of interest. For example, Ms. Hayes stated, "We spend a large chunk of time building background knowledge…I show videos,” she also discussed the types of questions she asks students on a given book topic to help build up her students’ schema. Strategy instruction. By far, the most used strategies implemented by the teachers were graphic organizers, visuals, and teacher prompting. The graphic organizers helped students write down their thinking, visuals such as anchor charts helped students refer back to previously learned skills or words and prompting while answering questions provided a way to stop, reorganize thoughts, and continue. Ms. Wilson discussed several times her use of graphic organizers to assist her students with ASD, stating “Sequence it, or organize information about characters or about the plot or anything like that.” When it comes to using strategies, the teachers mentioned it was often difficult for the students to "hold on" to the information and then refer back to it. Thus, the teachers discuss providing visual support that aids the student in “seeing” the pieces and putting them together to make meaning. All of the teachers mentioned intentionally using anchor charts to do this. Ms. O’Conner said, “I give hands-on examples when I'm able to, and then we write down the strategy on a big poster board in the front of the classroom so that they can use it as a reference sheet.” While many teachers considered the specific needs of their students when they are planning, others mentioned how sometimes strategies emerged during instruction. Either way, specific and common strategies for their students were embedded into all comprehension instruction. The teachers also all said that students benefitted from the practice and repetition of skills. Thus, many of them circled back to strategies previously introduced throughout the year as useful for their students with ASD. Supporting social, emotional, behavioral, and sensory needs. The teachers discussed supports and strategies that are needed for their students with ASD regarding their social, emotional, behavioral, and sensory needs. Specifically, they focused on needs for support in engagement and minimizing distractions; embedding structure or predictably of instruction; and support for social interactions. First, many of the teachers mentioned the use of individualized behavior charts to keep students motivated and engaged, typically including an incentive system. Likewise, teachers said that their students with ASD are often and easily distracted because of overstimulation or they may fixate on something, in particular. Thus, to support disengagement or lack of interest during reading comprehension, many of the teachers mentioned reducing 14

distractions as much as possible. For example, Ms. Wilson stated: Minimizing distractions, which sometimes can be in the form of getting them in a smaller group, but sometimes can be in just the physical environment of the classroom, or time of day that I might do the comprehension lesson, because maybe at some points during the day they're a little bit more focused than others. Also, teachers discussed that embedding structure and predictability in lessons is useful for students, and typically paired them with checklists used in various forms, such as tasks for independent reading, the entire reading block, or used during text-based discussions. When discussing a lesson, Ms. Cook stated, "if the lesson itself was in a simple structure, that set them up for success. The lesson went smoother if they could predict what was going to happen.” When reflecting on literacy block, Ms. McCarthy said, “Making it so that we have a consistent routine and procedure, with a visual chart to support seems to help my students with ASD have more success.” Finally, teachers often discussed the challenges students with ASD have with socialization, specifically understanding cues from others, accepting feedback from peers, or engaging in a discussion on a text with peers. Ms. McCarthy said, “I have one student, in particular, who's very sensitive to criticism so, if it requires somebody giving him feedback that's not a teacher, it's really tough for him to deal with that" Likewise, another teacher mentioned a particular student of hers has a difficult time picking up social cues of peers and shuts down during instruction. For example, the student thought his peers were laughing at him, so he fixated on it and struggled to reengage with the class. To help him understand and support his frustration the teacher prompted him to “look at the other people's faces, to figure out how they're feeling…I said, look at their faces, they're concerned about you. He's like, "Okay," and from there, I knew we could get back to work." Challenges to Comprehension Instruction While the teachers have found several practices and strategies that work for their students with ASD, they all mentioned ongoing challenges and areas they needed continued support to enhance students’ comprehension. Generalizing across texts. All the teachers mentioned the difficulty in having students with ASD generalize strategies and skills across texts. Although teachers scaffolded support by preteaching of skill and building of knowledge of a particular topic, a student might be able to pull out multiple inferences on the given text of instruction and support with evidence their responses; however, when asked to make inferences on a new text, many students were unable to utilize the strategies from the previously taught lessons and texts and transfer learning. When reflecting on their greatest challenge working with students with ASD, Ms. Rizzo said: The generalization part; taking a skill that they have learned and being able to apply it to different texts and being able to do it alone. For example, they're with me at our table, and we do our instructions, and then literally ten minutes later I'll ask them to do the same thing just at a different table, at a different story, and all of the sudden it's like, "I can't do this, I don't know

15

how to do this, what do I do?" It's also that anxiety. You know, maybe, "I don't know what to do, I can't do this, it's too hard. I can't remember. This isn't the exact wording. Oral text-based discussions. Also, all the teachers mentioned that a large part of comprehending text is being able to engage in discussion with peers, but that this was a significant challenge for their students with ASD. As mentioned, many times by the teachers, students with ASD needed ongoing prompting from a teacher to continue to engage with their peers on a text-based discussion. Likewise, teachers stated that many students would say something completely off-topic and unrelated to the text. Others mentioned, that unless the book was on a topic of complete interest to the student with ASD, they were unlikely to participate in the discussion. Ms. O’Conner mentioned; "It's hard for students with autism to attend to texts when they can't attend to the world around them.” Most of the teachers indicated this is one of their most significant challenges, and many felt defeated and unsure of how to support their students with ASD. To sum up her challenges, Ms. Edwards stated, "sometimes they just come up with something that is just to me it seems non sequitur… and I'm like how do I get them back here? I don't know that I have an effective strategy for that yet." Promoting independence. When discussing students’ independent practice, teachers were often at a loss on how to support their students with ASD. When reflecting on challenges, the teachers had little to say about how they support independence, tried to avoid giving students the time to work independently, or they used supportive measures that do not necessarily foster independence of the given skills. For example, Ms. Lee said, "giving students with autism too much independent time is difficult because often, there's comorbidity with autism and attention issues.” Similarly, Ms. Edwards said that during independent work time; “they are working with a computer-based program or with a paraprofessional because they are not able to complete the work independently." Discussion This descriptive study drew upon special education teachers’ experiences teaching reading comprehension to students with ASD in 4th to 8th grade. The analysis the findings yielded three broad themes that included instructional practices teachers used during comprehension instruction, instructional considerations for students with ASD, and the continued challenges teachers providing comprehension instruction for students with ASD experience. All of the teachers discussed in great detail their instructional strategies and supports when teaching comprehension to their students. First and foremost, common instruction for reading comprehension aligned with the general education curriculum but was often significantly adapted or differentiated. Curriculums used by the teachers focused on scope and sequences aiming at teaching comprehension strategies, which supports evidence-based practices. Research shows that teaching students to comprehend requires evidence-based practices such as the use of explicit instruction (Van Keer, 2004) strategy instruction (Gersten, Fuchs, Williams, Baker, 2001), building metacognition, and inferencing skills (Cross & Paris, 1988). The findings of this study demonstrate the special education teachers in this study used a variety of these strategies, including using explicit instruction through gradual release models, by first modeling new skills 16

and strategies with complex texts, providing opportunities for students to practice with feedback as well as embedding some independent practice opportunities. Building comprehension does not stop at the strategies listed above; it also includes vocabulary instruction (Bos & Anders, 1990). Research shows the connection between vocabulary instruction and students' comprehension (Wright & Cervetti, 2017). Students need a robust vocabulary and to be able to pull from it to comprehend rigorous texts (Rimbey, McKeown, Beck, & Sandora, 2016). The interviews with these teachers demonstrated that all teachers in the study considered the development of their students’ vocabulary. Finally, whether a special education or general education teacher, differentiation strategies should be considered when teaching comprehension to students (Tomlinson, 2014). Each classroom has a diverse set of learners with a variety of needs; thus, teachers need to consider the wide range of needs in supporting their students. Differentiation is generally defined as accommodating students with different strengths and areas of need in all areas of reading including levels, learning style, interest, background knowledge, experiences, and culture, including ethnicity, race, economic level, and disability, thus teaching in the "middle" will not meet the needs of every learner regardless of the classroom setting (Valiandes, 2015). The special education teachers were adamant about the use of small groups as a way to differentiate instruction. Teachers used a variety of strategies for determining the nature of their small groups including, reading levels, specific skills students were working on, heterogeneous groups so students could support one another, and lastly groups were even designed based on behavioral or social needs to set students up for success. This practice aligns with research that shows that small group work is a successful tool for differentiating instruction and should be utilized as much as possible in all educational settings (Fisher & Frey, 2014). Though not explicitly mentioned by the teachers, it is important to note the difference between listening and reading comprehension. While many of the teachers spoke about their reading comprehension instruction, the true focus of their instruction and even independent practice of skills and strategies was often focused on listening comprehension. Reading comprehension involves the interpretation of printed text (Israel & Duffy, 2017), while listening comprehension is the interpretation of the spoken text (Nadig, 2013). The bulk of the instructional practices discussed by the teachers in this study focused on their modeling of skills using short, yet complex text read aloud to students. Also, students were asked to discuss the meaning of a text with a partner after listening to the teacher read it aloud. As mentioned by the teachers, much of the independent practice opportunities were supported by the teachers themselves or a paraprofessional where the students were practicing these skills in a small group or one-on-one. While the research on comprehension instruction for students with ASD is growing, this study found some similarities to current research in instructional practices for students with ASD. The teachers in this study all found common strategies that tend to work for their students with ASD to enhance their comprehension including the use of visual supports, graphic organizers, and prompting as some of the most prominently used. All these strategies noted have shown positive outcomes in improving reading comprehension for students with ASD (Knight & Sartini, 2015). Also, many of the teachers in this study mentioned that building student background knowledge was a key strategy for supporting students with ASD. This is similar to research stating that background knowledge is a crucial component of reading comprehension. Going beyond this is 17

not only building knowledge but encouraging students to activate and use it. The teachers in this study said this required building up students’ interests in a topic in a variety of ways. Thus, teachers spent much time using a variety of modalities to get students excited about a given topic, especially those unfamiliar to the student. Research on students with ASD show that they perseverate on topics they are interested in (El Zein, Solis, Lang, & Kim, 2016), thus, to bring in new interests, teachers must go beyond basic background knowledge building to get students excited about new topics. Similar to findings by Brock et al. (2014) teachers indicated that they were not completely comfortable teaching literacy to students with ASD; thus, educational leaders must consider how to prepare them better through teacher preparation programs. The findings in this study demonstrate that the special education teachers still have challenges helping students with ASD transfer and generalize their learning from one lesson or skill to the next. The teachers mentioned going beyond the explicitness of a text was important, but many teachers found it challenging to help students build up the skills needed to make meaningful inferences. Also, most of the teachers felt at a loss for how to support students with ASD to engage in discussions around a text and beyond the explicitness, or even on the task. Recent research demonstrates that educators typically face these types of challenges when working with students who have ASD (Emam & Farrell, 2009) and need support to provide them with the appropriate instruction. For example, teachers struggled to develop an understanding of the cognitive process students with ASD go through to develop a text, or they're developing not only the comprehension of individual words but a group of words together. Due to their unique social and communication deficits, teachers also struggled in having students with ASD use strategies that would develop their reading comprehension such as having them engage in meaningful discourse on text (Randi, Newman, & Grigorenko, 2010). Implications for Practice Adaptations of reading instruction. Considerations for adaptations for reading instruction is crucial for all educators. Adaptations are defined as: (a) additional strategies implemented (e.g. modeling, direct instruction); (b) providing other supports (e.g. use of audio, chunking texts, offering choices in responses, applying behavior chart); or (c) omissions (e.g. reducing time on instructional tasks, removing unnecessary text, distracting images, or skills introduced) to the standard protocol intervention (Backer, 2001). In a recent study examining teachers’ comfortability in adapting instruction the results showed that teachers who were more comfortable with the key components of an intervention were also confident in their unique contextual needs (e.g. content area, instructional setting) and supports such as resources(e.g. collaborative partnerships with peers), provided instruction with more fidelity, and made appropriate adaptations to meet individual needs thus leading to more positive outcomes for the student (Leko, et al., 2014). When considering students with ASD, teachers must be able to identify the specific needs of their students; thus, educators need to adequately assess their students, identify their strengths and areas of need and consider common characteristics for difficulties in reading for their students. Although we know there are some commonalities across reading behaviors, specifically for reading comprehension for students with ASD, we also know that certain oral language, 18

social, and emotional deficits can play a role in the difficulties students have with reading comprehension (Randi et al., 2010); therefore, educators must adapt instruction to meet the unique needs of each of their students. To do so, educators need appropriate preparation, tools, and resources (Brock et al., 2014). Adapting instruction to meet the unique needs of students is critical, especially for reading instruction for students with ASD. Research has demonstrated that adaptations to reading instruction often have a significant impact on outcomes for students, even if the implementation fidelity of the lesson is not intact, and teachers need support through professional development and contextual coaching to understand how to best adapt components to the interventions and instructional strategies used (Harn, Parisi, & Stoolmiller, 2013). Enhancing literacy instruction for teachers of students with ASD. While having to cover a vast amount of content knowledge, pedagogy, and practice (Brownell, Sindelar, Kiely, & Danielson, 2010), teacher preparation programs often lack sufficient time or knowledge to adequately prepare teachers with all of the skills needed to meet individual student needs (Leko, Brownell, Sindelar, & Kiely, 2015). Much of the pre-service preparation for teachers working with students with ASD has focused on social and emotional learning (Barnhill, Sumutka, Polloway, & Lee, 2014) or legal requirements and eligibility classification (Morrier, Hess, & Heflin, 2011). Hence, teachers are often struggling to make the right instructional decisions for their students with ASD, specifically in reading. Researchers indicate that students with ASD need explicit implementations of complex teaching procedures (McGee & Morrier, 2005); however, there is little research on what teachers who work with these students need, and the research available focuses mostly on programs for social and behavioral development (Barnhill et al., 2014; Brock et al., 2014). As a result, many researchers (e.g., Barnhill, et al., 2014; Brewin, Renwick, & Schormans, 2008; Campbell, 2007; Carrington, Templeton, & Papinczak, 2003; Starr & Foy, 2010) suggest further investigations to help both general and special education teachers understand reading challenges and strategies for students with ASD including increasing the number of observational studies examining teacher practices (Brock et al., 2014). Adequately preparing educators is a twofold process, first through appropriate pre-service education programs, and secondly through ongoing professional development and support. In recent years with the change of special education laws for teacher preparation, all educators must be well prepared to teach students with ASD, since more and more students are provided with literacy instruction in general education classrooms (Segall, 2012). Though it is crucial for preservice preparation programs to continue to refine their curriculum to align with updated policy and research (Brownell, Ross, Colón, & McCallum, 2005; DeLuca, & Bellara, 2013). There is also a continued need to provide teachers with support while in the classroom (Buell, Hallam, Gamel-Mccormick, & Scheer, 1999) and to continue to build skills and knowledge, and support unique and natural settings (Brownell et al., 2005). References Adomat, D. S. (2012). Drama’s potential for deepening young children’s understandings of stories. Early Childhood Education Journal, 40(6), 343-350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0519-8 American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington, VA: Author. 19

Backer, T. E. (2001). Finding the balance: Program fidelity and adaptation in substance abuse prevention: A state-of-the-art review. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. Barnhill, G. P., Sumutka, B., Polloway, E. A., & Lee, E. (2014). Personnel preparation practices in autism: A follow-up analysis of contemporary practices. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 29(1), 39-49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357612475294 Bellini, S., Peters, J. K., Benner, L., & Hopf, A. (2007). A meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 28(3), 153-162. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325070280030401 Bos, C. S., & Anders, P. L. (1990). Effects of interactive vocabulary instruction on the vocabulary learning and reading comprehension of junior-high learning-disabled students. Learning Disability Quarterly, 13(1), 31-42. https://doi.org/10.2307/1510390 Brock, M. E., Huber, H. B., Carter, E. W., Juarez, A. P., & Warren, Z. E. (2014). Statewide assessment of professional development needs related to educating students with autism spectrum disorder. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 29(2), 67 79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357614522290 Brown, H. M., Oram-Cardy, J., & Johnson, A. (2013). A meta-analysis of the reading comprehension skills of individuals on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(4), 932-955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1638-1 Brownell, M. T., Ross, D. D., Colón, E. P., & McCallum, C. L. (2005). Critical features of special education teacher preparation: A comparison with general teacher education. The Journal of Special Education, 38(4), 242-252. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224669050380040601 Brownell, M. T., Sindelar, P. T., Kiely, M. T., & Danielson, L. C. (2010). Special education teacher quality and preparation: Exposing foundations, constructing a new model. Exceptional Children, 76(3), 357-377. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007600307 Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Cook, B. G., & Odom, S. L. (2013). Evidence-based practices and implementation science in special education. Exceptional Children, 79(2), 135-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291307900201 Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Autism Spectrum Disorder. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html Chiang, H. M., & Lin, Y. H. (2007). Reading comprehension instruction for students with autism spectrum disorders a review of the literature. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22(4), 259-267. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576070220040801 Creswell, J.W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Cross, D. R., & Paris, S. G. (1988). Developmental and instructional analyses of children's metacognition and reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(2), 131-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.2.131 Emam, M. M., & Farrell, P. (2009). Tensions experienced by teachers and their views of support for pupils with autism spectrum disorders in mainstream schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 24(4), 407-422. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250903223070 20

El Zein, F., Solis, M., Lang, R., & Kim, M. K. (2016). Embedding perseverative interest of a child with autism in text may result in improved reading comprehension: A pilot study. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 19(3), 141-145. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2014.915893 El Zein, F., Solis, M., Vaughn, S., & McCulley, L. (2014). Reading comprehension interventions for students with autism spectrum disorders: A synthesis of research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(6), 1303-1322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013 1989-2 Finnegan, E., & Mazin, A. L. (2016). Strategies for increasing reading comprehension skills in students with autism spectrum disorder: a review of the literature. Education and Treatment of Children, 39(2), 187-219. DOI:10.1353/etc.2016.0007 Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2014). Close reading as an intervention for struggling middle school readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 57(5), 367-376. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.266 Fleury, V. P., Hedges, S., Hume, K., Browder, D. M., Thompson, J. L., Fallin, K., ... & Vaughn, S. (2014). Addressing the academic needs of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder in secondary education. Remedial and Special Education, 35(2), 68-79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932513518823 Flores, M. M., & Ganz, J. B. (2007). Effectiveness of direct instruction for teaching statement inference, use of facts, and analogies to students with developmental disabilities and reading delays. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22(4), 244251. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576070220040601 Flores, M. M., & Ganz, J. B. (2009). Effects of direct instruction on the reading comprehension of students with autism and developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 39-53. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24233462 Gately, S. E. (2008). Facilitating reading comprehension for students on the autism spectrum. Teaching Exceptional Children, 40(3), 40-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990804000304 Gersten, R., Fuchs, L. S., Williams, J. P., & Baker, S. (2001). Teaching reading comprehension strategies to students with learning disabilities: A review of research. Review of Educational Research, 71(2), 279-320. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543071002279 Goodman, L. A. (1961). Snowball sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 32(1) 148170. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2237615 Harn, B., Parisi, D., & Stoolmiller, M. (2013). Balancing fidelity with flexibility and fit: What do we really know about fidelity of implementation in schools? Exceptional Children, 79(2), 181-193. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291307900204 Hibbing, A. N., & Rankin-Erickson, J. L. (2003). A picture is worth a thousand words: Using visual images to improve comprehension for middle school struggling readers. The Reading Teacher, 56(8), 758-770. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20205292 Huber, H. B., & Carter, E. W. (2016). Data-driven individualization in peer-mediated interventions for students with ASD: A literature review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 3(3), 239-253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-016-0079-8 Hughes, C., Golas, M., Cosgriff, J., Brigham, N., Edwards, C., & Cashen, K. (2011). Effects of a social skills intervention among high school students with intellectual disabilities and autism and their general education peers. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe 21

Disabilities, 36(1-2), 46-61. https://doi.org/10.2511/rpsd.36.1-2.46 Israel, S. E., & Duffy, G. G. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of research on reading comprehension. New York: Routledge. Kamps, D. M., Barbetta, P. M., Leonard, B. R., & Delquadri, J. (1994). Class-wide peer tutoring: An integration strategy to improve reading skills and promote peer interactions among students with autism and general education peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(1), 49-61. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1994.27-49 Kamps, D. M., Leonard, B., Potucek, J., & Garrison-Harrell, L. (1995). Cooperative learning groups in reading: An integration strategy for students with autism and general classroom peers. Behavioral Disorders, 21(1), 89-109. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874299502100103 Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2(3), 217-250. Retrieved from: http://mail.neurodiversity.com/library_kanner_1943.pdf Keen, D., Webster, A., & Ridley, G. (2016). How well are children with autism spectrum disorder doing academically at school? An overview of the literature. Autism, 20(3), 276294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315580962 Kluth, P., & Chandler-Olcott, K. (2008). A land we can share: Teaching literacy to students with autism. Baltimore, MD: PH Brookes Pub. Knight, V. F., & Sartini, E. (2015). A comprehensive literature review of comprehension strategies in core content areas for students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(5), 1213-1229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803014-2280-x Leblanc, L., Richardson, W., & Burns, K. A. (2009). Autism spectrum disorder and the inclusive classroom: Effective training to enhance knowledge of ASD and evidence-based practices. Teacher Education and Special Education, 32(2), 166-179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932507334279 Leko, M. M., Brownell, M. T., Sindelar, P. T., & Kiely, M. T. (2015). Envisioning the future of special education personnel preparation in a standards-based era. Exceptional Children, 82(1), 25-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402915598782 Leko, M. M., Roberts, C. A., & Pek, Y. (2014). A theory of secondary teachers’ adaptations when implementing a reading intervention program. The Journal of Special Education, 49(3), 168-178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466914546751 Loiacono, V., & Valenti, V. (2010). General education teachers need to be Prepared to co-teach the increasing number of children with autism in inclusive settings. International Journal of Special Education, 25(3), 24-32. McIntyre, N. S., Solari, E. J., Grimm, R. P., Lerro, L. E., Gonzales, J. E., & Mundy, P. C. (2017). A comprehensive examination of reading heterogeneity in students with high functioning autism: Distinct reading profiles and their relation to Autism Symptom Severity. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(4), 1086-1101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3029-0 Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons. Metros, S. E. (2008). The educator's role in preparing visually literate learners. Theory into Practice, 47(2), 102-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840801992264 Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 22

Mitchell, D. (2007). What really works in special and inclusive education: Using evidence-based teaching strategies. New York, NY: Routledge. Morrier, M. J., Hess, K. L., & Heflin, L. J. (2011). Teacher training for implementation of teaching strategies for students with autism spectrum disorders. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 34(2), 119-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406410376660 Nadig, A. (2013). Listening comprehension. In Fred R. Volkmar (Ed.). The Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-16983_349 Nation, K., Clarke, P., Wright, B., & Williams, C. (2006). Patterns of reading ability in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 911–919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0130-1 National Institute of Mental Health. (2015). Autism Spectrum Disorder Retrieved from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning reports/index.shtml O'Connor, I. M., & Klein, P. D. (2004). Exploration of strategies for facilitating the reading comprehension of high-functioning students with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(2), 115-127. Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Pine, E., Luby, J., Abbacchi, A., & Constantino, J. N. (2006). Quantitative assessment of autistic symptomatology in preschoolers. Autism, 10(4), 344-352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361306064434 Randi, J., Newman, T., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2010). Teaching children with autism to read for meaning: Challenges and possibilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(7), 890-902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0938-6 Ricketts, J., Jones, C. R., Happé, F., & Charman, T. (2013). Reading comprehension in autism spectrum disorders: The role of oral language and social functioning. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(4), 807-816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-16194 Rimbey, M., McKeown, M., Beck, I., & Sandora, C. (2016). Supporting teachers to implement contextualized and interactive practices in vocabulary instruction. Journal of Education, 196(2), 69-83. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741619600205 Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Saldaña, D., & Frith, U. (2007). Do readers with autism make bridging inferences from world knowledge? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 96(4), 310-319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2006.11.002 Secan, K. E., & Mason, G. (2013). Services that span the autism spectrum. School Administrator, 70(2), 29-33. Shukla-Mehta, S., Miller, T., & Callahan, K. J. (2010). Evaluating the effectiveness of video instruction on social and communication skills training for children with autism spectrum disorders: A review of the literature. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 25(1), 23-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357609352901 Stringfield, S. G., Luscre, D., & Gast, D. L. (2011). Effects of a story map on accelerated reader post-reading test scores in students with high-functioning autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 26(4), 218-229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357611423543 23

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. U.S. Department of Education, (2018). Digest of Education Statistics, 2016 (NCES 2017-094). Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/ch_2.asp Valiandes, S. (2015). Evaluating the impact of differentiated instruction on literacy and reading in mixed ability classrooms: Quality and equity dimensions of education effectiveness. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 45, 17-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.02.005 Van Keer, H. (2004). Fostering reading comprehension in fifth grade by explicit instruction in reading strategies and peer tutoring. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74(1), 37-70. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709904322848815 Wang, P., & Spillane, A. (2009). Evidence-based social skills interventions for children with autism: A meta-analysis. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 44(3) 318-342. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24233478 Whalon, K., & Hanline, M. F. (2008). Effects of a reciprocal questioning intervention on the question generation and responding of children with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 43(3), 367-387. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23879798 Williamson, P., Carnahan, C. R., & Jacobs, J. A. (2012). Reading comprehension profiles of high-functioning students on the autism spectrum: A grounded theory. Exceptional Children, 78(4), 449-469. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291207800404 Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K. A., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., ... & Schultz, T. R. (2015). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 1951-1966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2351-z Wright, T. S., & Cervetti, G. N. (2017). A systematic review of the research on vocabulary instruction that impacts text comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 52(2), 203226. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.163 About the Authors Gina Braun, PhD., is a professor of special education at Rockford University in Rockford, Illinois. Dr. Braun teaches a wide range of special education courses such as Survey of Exceptional Children, Instructional Methods for Diverse Learners, and Positive Behavior Supports. The focus of her research is supporting early-career teachers’ instructional practices for enhancing reading comprehension skills to students with autism spectrum disorder. Marie Tejero Hughes, Ph.D., is a professor of special education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is the director of graduate studies for the Department of Special Education and a Faculty Fellow in the Honors College. Dr. Tejero Hughes primarily teaches graduate courses in literacy designed for general and special education teachers working in urban communities. Her areas of expertise include learning disabilities, comprehension instruction for students struggling with reading, and Latino family engagement in education.

24

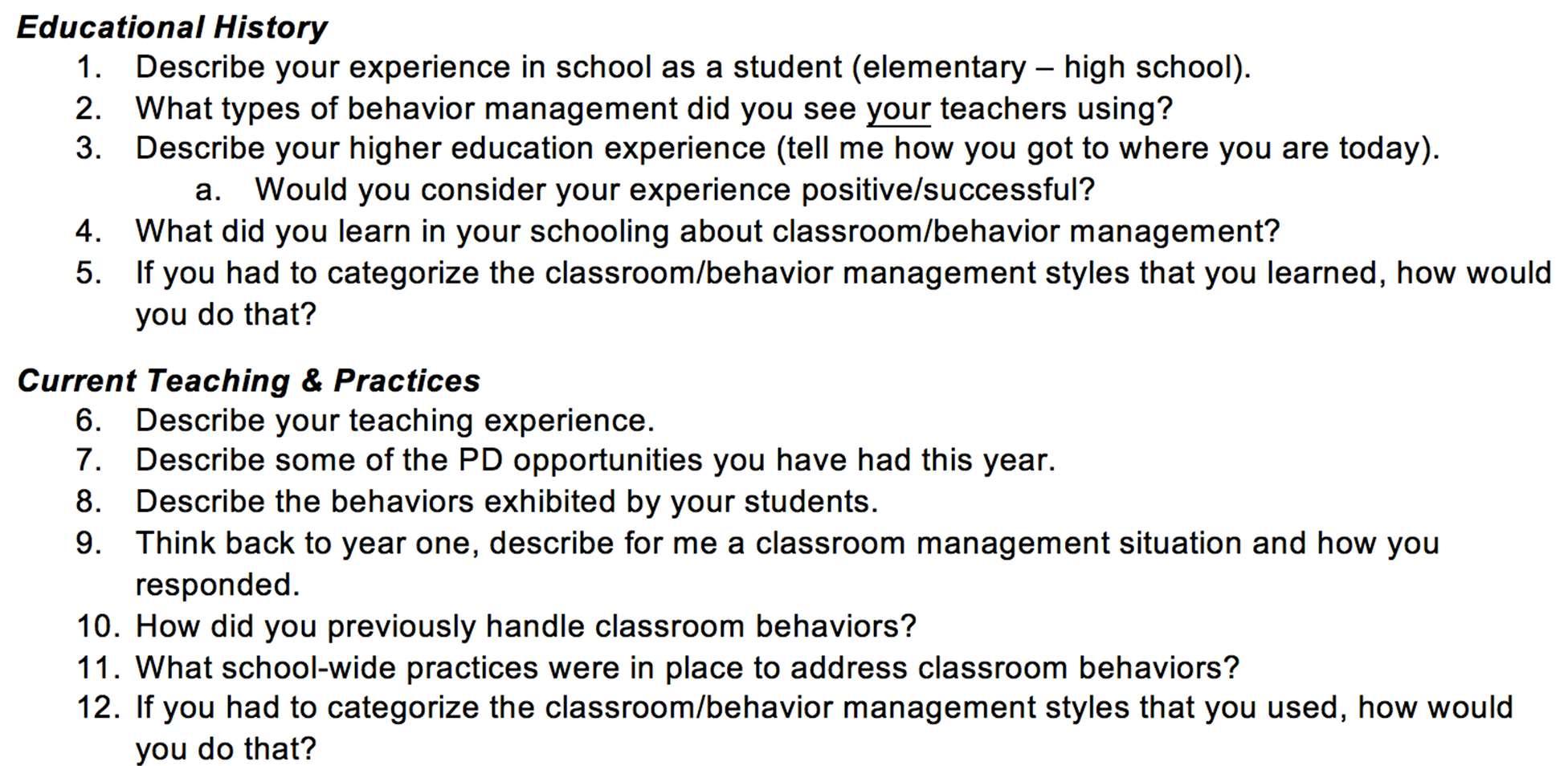

Appendix A Teacher Interview General Reading Comprehension 1. Could you describe the way you teach reading comprehension? Probe: What is a typical day? Probe: Do you include reading out loud? What does this look like? Probe: What does vocabulary instruction look like in your classroom? Probe: Do you teach comprehension strategies? Describe. (i.e., Summarization, questioning) 2. How do you know if students are comprehending a text? Probe: what is a good response? What is a poor response? 3. What indicates to you that a comprehension lesson is going well? Probe: poorly? 4. How do you adapt comprehension instruction for your learners? Probe: Do you divide students into groups? On what basis? Why? Do you change the groups? Why? Autism and Reading Comprehension 5. When planning your reading comprehension lessons, how do you consider the needs of your students with autism? Compared to other students you have taught; do you find it easy or difficult to adapt your lesson plans to support students with autism? Why? Probe: How do you differentiate your plans for your students with autism? 6. Describe the types of reading/reading instructional strategies you utilize when teaching reading comprehension to students with autism. Probe 1: What strategies and supports are most useful to teaching reading comprehension to students with autism? Probe 2: What strategies and supports are least useful for teaching students reading comprehension to students with autism? 7. What works well for you when teaching reading comprehension to students with autism (Probe: educationally, and socially)? In thinking about social deficits for kids with autism? What works well? 8. In your experience, what are the greatest difficulties encountered in teaching reading/reading instructional strategies to your students with autism? 9. Do you have any suggestions/advice on how to prepare educators to teach reading to students 25

with autism? 10. Is there anything else in regard to teaching reading instruction to students with autism that we haven't talked about that you would like to comment on? Teacher Experience and Educational Background To end our interview, I will ask you a few questions that will assist me in describing the group of teachers I am interviewing. What grades and subjects do you teach? How many years have you taught? How did you obtain your teaching certification? (i.e., 4-year university, alternative program) What is your current level of education (i.e., masters, bachelors, etc.)? Tell me a bit about your coursework in your pre-service or Masters preparation program related to reading? Students with disabilities? Autism? How long have you taught students with autism?

26