Dialog Dialog Dialóg

Angažovanost prostřednictvím kultury před rokem 1989 a po něm

← 1989 →

Kultura zaangażowana przed rokiem 1989 oraz po nim

Kultúrne angažmá pred rokom 1989 a po ňom

Dialog

Angažovanost prostřednictvím kultury před rokem 1989 a po něm

Text: Barbora Baronová

Fotografie: Ján Kekeli, Witek Orski, Dita Pepe Grafický design: Adéla Svobodová

Kurátorka textové části: Barbora Baronová

Kurátor fotografické části: Robert Švarc

Jazyková spolupráce: Lenka Hroncová, Marie Hvozdecká, Kateřina Kadlecová, Dorota Kaminska Pawlas, Martyna

Szczepaniak-Woźnikowska, Izabela Walaská, Petra Zrníková

Překlady: Sylva Ficová, Lenka Hroncová, Anne Johnson, Martyna Szczepaniak-Woźnikowska a Paweł Woźnikowski (Translatorion)

Produkce katalogu: Barbora Baronová (wo-men) Tisk katalogu: Helbich

Realizátorem projektu jsou Česká centra

Partneři projektu: Štokovec, priestor pre kultúru Galeria Arsenał Centre for Fine Arts (BOZAR), Brussels Jazz Station Big Band asbl

Financováno v rámci programu Evropské unie „Evropa pro občany“

Projekt Engagement Through Culture Before and After 1989 je realizován na základě grantového rozhodnutí EACEA 2 18-1819/ 1- 1.

Podpora Evropské komise při realizaci této publikace neznamená souhlas Evropské komise s jejím obsahem, který odráží pouze názory autorů. Evropská komise nenese odpovědnost za jakékoli využití informací obsažených v této publikaci.

Dialog

Kultura zaangażowana przed rokiem 1989 oraz po nim

Tekst: Barbora Baronová

Zdjęcia: Ján Kekeli, Witek Orski, Dita Pepe Projekt graficzny: Adéla Svobodová

Kuratorka części tekstowej: Barbora Baronová

Kurator części fotograficznej: Robert Švarc

Współpraca językowa: Lenka Hroncová, Marie Hvozdecká, Kateřina Kadlecová, Dorota Kaminska Pawlas, Martyna Szczepaniak-Woźnikowska, Izabela Walaská, Petra Zrníková

Tłumaczenia: Sylva Ficová, Lenka Hroncová, Anne Johnson, Martyna Szczepaniak-Woźnikowska i Paweł Woźnikowski (Translatorion)

Produkcja katalogu: Barbora Baronová (wo-men) Druk katalogu: Helbich

Realizatorem projektu są Czeskie Centra

Partnerzy projektu: Štokovec, priestor pre kultúru Galeria Arsenał Centre for Fine Arts (BOZAR), Brussels Jazz Station Big Band asbl

Finansowany w ramach unijnego programu „Europa dla obywateli”

Projekt Engagement Through Culture Before and After 1989 został zrealizowany w oparciu o decyzję EACEA 2 18-1819/ 1- 1.

Wsparcie Komisji Europejskiej udzielone niniejszej publikacji nie oznacza, że Komisja popiera wyrażone w niej poglądy, które są wyłącznie poglądami autorów publikacji. W związku z powyższym Komisja nie ponosi odpowiedzialności za żadnego rodzaju wykorzystanie informacji zawartych w niniejszej publikacji.

Dialóg Kultúrne angažmá

pred rokom 1989 a po ňom

Text: Barbora Baronová

Fotografia: Ján Kekeli, Witek Orski, Dita Pepe Grafický design: Adéla Svobodová

Kurátorka textovej časti: Barbora Baronová Kurátor fotografickej časti: Robert Švarc

Jazyková spolupráca: Lenka Hroncová, Marie Hvozdecká, Kateřina Kadlecová, Dorota Kaminska Pawlas, Martyna

Szczepaniak-Woźnikowska, Izabela Walaská, Petra Zrníková

Preklady: Sylva Ficová, Lenka Hroncová, Anne Johnson, Martyna Szczepaniak-Woźnikowska a Paweł Woźnikowski (Translatorion)

Produkcia katalógu: Barbora Baronová (wo-men) Tlač katalógu: Helbich

Realizátorom projektu sú České centrá

Partneri projektu: Štokovec, priestor pre kultúru Galeria Arsenał Centre for Fine Arts (BOZAR), Brussels Jazz Station Big Band asbl

Financované programom Európskej únie „Európa pre občanov“

Projekt Engagement Through Culture Before and After 1989 vznikol na základe rozhodnutia EACEA 2 18-1819/ 1- 1.

Podpora Európskej komisie na tvorbu tejto publikácie neznamená súhlas s jej obsahom, ktorý odráža len názory autorov, a Komisia nemôže niesť zodpovednosť za akékoľvek použitie informácií, ktoré sú obsahom tejto publikácie.

Projekt Dialog. Angažovanost prostřednictvím kultury před rokem 1989 a po něm představuje dvanáct perspektiv kulturních osobností ze tří zemí středoevropského prostoru – z České republiky, ze Slovenska a z Polska. Přímí aktéři společenských změn, které před třiceti lety v totalitním bloku vedly k nastolení demokracie, vyjadřují v rozhovorech své postoje nejen k bývalému režimu a politickým událostem roku 1989, ale také k vývoji a novému postavení postkomunistických zemí v rámci Evropy. Postojově, generačně i genderově rozmanité hlasy připomí nají a komentují rozhodující okamžiky a historické etapy ovlivňující svým významem celý region – vznik Charty 77, šestadvacet let trvající pontifikát Jana Pavla II., zrod polského hnutí Solidarita, sametovou revoluci, nástup prezidenta Václava Havla, rozdělení Československa, období mečiarismu, leteckou tragédii u Smolenska, ale i loňskou vraždu slovenského novináře Jána Kuciaka a jeho snoubenky Martiny Kušnírové. Zároveň všech dvanáct osobností přizvaných k dialogu reflektuje podstatné změny v mezilidské rovině (ať už vlivem rostoucího blaho bytu, nebo nástupu nových technologií) a zpracovává zmíněná témata i ve své vlastní práci prostřednictvím filmu, hudby, literatury, výtvarného umění, vydavatelské praxe, performance a happeningů, přednášek nebo novinových článků, čímž ve své domovině nastoluje potřebný intelektuální diskurz. Vyrovnaný dialog totiž znamená svobodu.

Projekt Dialog. Kultura zaangażowana przed rokiem 1989 oraz po nim przedstawia punkty widzenia dwanaściorga ludzi kultury z trzech krajów Europy Środkowej: Czech, Słowacji i Polski. Bezpośredni uczestnicy zmian spo łecznych, które doprowadziły do ustanowienia demokracji w państwach bloku wschodniego trzydzieści lat temu, opowiadają o swoim stosunku do minionego reżimu i wydarzeń politycznych roku 1989 oraz do rozwoju i nowej sytu acji państw postkomunistycznych w Europie. Wywiady prezentują zróżnicowane głosy i postawy przedstawicieli róż nych pokoleń i płci, którzy wspominają i oceniają najbardziej przełomowe i historyczne momenty, jakie wywarły wpływ na tę część kontynentu – utworzenie Karty 77, trwający 26 lat pontyfikat Jana Pawła II, narodziny ruchu Solidarności w Polsce, aksamitną rewolucję, prezydencję Václava Havla, rozpad Czechosłowacji, okres rządów Vladimíra Mečiara, katastrofę smoleńską oraz zamordowanie słowackiego dziennikarza Jána Kuciaka i jego narzeczo nej Martiny Kušnírovej w 2 18 roku. Rozmówcy dzielą się swymi refleksjami na temat istotnych zmian dotyczących relacji międzyludzkich (wynikających zarówno ze wzrostu zamożności społeczeństwa, jak i z postępu nowych tech nologii) oraz odnoszą się do różnych wątków w swojej własnej twórczości w dziedzinie filmu, muzyki, literatury, sztuk wizualnych i performatywnych, happeningów, działań wydawniczych, wykładów i artykułów prasowych, inicjując w ten sposób potrzebną debatę intelektualną w swych ojczyznach. Wszak zrównoważony dialog oznacza wolność.

Projekt Dialóg. Kultúrne angažmá pred rokom 1989 a po ňom predstavuje dvanásť perspektív kultúrnych osobností z troch krajín stredoeurópskeho priestoru – z Českej republiky, zo Slovenska a z Poľska. Priami aktéri spo ločenských zmien, ktoré pred tridsiatimi rokmi v totalitnom bloku viedli k nastoleniu demokracie, vyjadrujú v rozhovoroch svoje postoje nielen k bývalému režimu a politickým udalostiam roku 1989, ale tiež k vývoju a novému postaveniu postkomunistických krajín v rámci Európy. Postojovo, generačne i genderovo rozmanité hlasy pripomínajú a komentujú rozhodujúce okamihy a historické etapy ovplyvňujúce svojím významom celý región – vznik Charty 77, dvadsaťšesť rokov trvajúci pontifikát Jána Pavla II., zrod poľského hnutia Solidarita, zamatovú revolúciu, nástup prezidenta Václava Havla, rozdelenie Československa, obdobie mečiarizmu, leteckú tragédiu pri Smolensku, ale aj vlaňajšiu vraždu slovenského novinára Jána Kuciaka a jeho snúbenice Martiny Kušnírovej. Zároveň všetkých dvanásť osobností prizvaných k dialógu reflektuje podstatné zmeny v medziľudskej rovine (či už vplyvom rastúceho blahobytu, alebo nástupu nových technológií) a spracováva spomínané témy aj vo svojej vlastnej práci prostredníctvom filmu, hudby, literatúry, výtvarného umenia, vydavateľskej praxe, per formance a happeningov, prednášok alebo novinových článkov, pričom vo svojej domovine nastoľuje potrebný inte lektuálny diskurz. Vyrovnaný dialóg totiž znamená slobodu.

Saša Uhlová

» Sašo, co to znamenalo, být dítětem dvou chartistů?

Ještě než tátu zavřeli, mám vzpomínku, jak se ho držím za nohu. Bylo mně rok a půl, když šel do vězení, a vrátil se, když jsem končila první třídu. Z raného dětství si tak pamatuji jenom mámu. Zadržování, domovní prohlídky, to dělali hlavně po tom, co se táta vrátil, až do revoluce. Z dětství se mi vybavuje hlavně komunita lidí, kteří se u nás doma scházeli, a akce, které společně pořádali, ať už to byly pik niky, oslavy Silvestra nebo různé večírky. S kamarádkami, hlavně máminými, jsme jezdívali na chalupu, na to vzpomínám ráda. Ale negativně mě ovlivnila úzkost, kte rou jsem tehdy cítila, a vlastně s ní bojuji dodnes. Táta byl ve vězení a já věděla, že mohou zavřít i mámu, taky už byla předtím ve vězení. Když nebyla doma, bála jsem se, že ji určitě někde zadržují, a co s námi bude, že nás dají do dětského domova. Takže jsem byla jako dítě vzorná, neukradla jsem nikdy ani bonbón, protože jsem měla strach, že by to mohlo dopadnout špatně. Máma o tom tenkrát nemluvila, zjistila jsem to až po revoluci, že měla sepsaný papír, aby nás, děti, dostal do péče její táta.

A snad by se o nás postarali i rodinní kamarádi Bískovi. Když za námi policie jednou

přijela na chalupu, kterou jsme si pronajímali, a mámu zatýkali, nechala nás odvézt na nedalekou faru právě k Bískovým, než aby nás dala hlídat bachařce. Když se pak táta vrátil z vězení, majitelé chalupy nám ji nechtěli dál pronajímat, protože jim vyhrožovali. Nechali nás tam jezdit ještě rok, ale pak řekli, že dál nemůžou. Byla to taková drobná šikana. Ale vůbec nejhorší byl pocit, že bych nemohla být s mámou.

» Co se změnilo, když se táta vrátil domů?

Změnilo se toho hodně. Tátovi vězení nepřidalo, byl v něm dvakrát, jednou ještě před mým narozením. Ze začátku k nám třeba domů přestaly chodit návštěvy, proto že je „nesnášel“. Dal na dveře seznam dvaceti lidí, kteří k nám mohli přijít bez ohlášení, ale všichni ostatní se museli začít hlásit. To nebývalo zvykem; bydleli jsme v centru a lidi prostě zazvonili a šli dál. Trvalo to jen nějakou dobu, táta asi potřeboval větší klid. Byl puntičkář, hodně dbal na pořádek a furt vyšetřoval, co kde leží. Taky byl hodně urputný. Začal se se mnou a bráchou učit francouzsky, takže jsem dnes bilingvní, ve Francii jsem pak i studovala. Měl metodu „každý den aspoň dvacet minut“, ale ve skutečnosti to bývalo minimálně hodinu a půl. I v létě o prázdninách jsme seděli na koupališti a celé odpoledne se učili. Ale francouzšti nu mě naučil a dnes je jediným cizím jazykem, který umím pořádně. Jeho návrat z vě zení byl pro mě vlastně překvapením. Měli jsme doma jeho fotku, věděli jsme, že je nespravedlivě zavřený, že je hrdina, že se bude vracet domů. Těšili jsme se na něj. Ale potom byl ten střet s člověkem natolik poničeným kriminálem komplikovaný. Cestu k němu jsem si našla až před čtyřmi roky, kdy to vypadalo, že umírá. Dostal se z toho a já jsem vděčná za ten čas.

» Co v tobě zanechaly disidentské návštěvy, které se u vás doma střídaly?

Nevím, co je moje povaha a do jaké míry mě ovlivnily návštěvy, ale dodnes mám ráda, když k nám lidi chodí – tu přijde dvacet kamarádů, jindy u nás někdo rok bydlí. Můj muž, který vyrostl jako jedináček v paneláku v Duchcově, se na začátku našeho manželství dost divil, ale už si zvykl. Návštěvy jsem milovala, aspoň nebyla nuda. Vždycky jsem je poslouchala, i když se dohadovali. Naopak jsem neměla ráda, když šeptali – to jsem pak napínala uši a nemohla jsem spát.

Často k nám chodila třeba paní Květa, která byla ještě v Brně zavřená s mým dědou a maminkou. Pak se přestěhovala do Prahy, a protože sama neměla děti, chodila s námi každý den odpoledne ven. I když nebyla z žádné těžce intelektuální rodiny, přesně věděla, co je správné a co ne. Vzpomínám taky na veselého Vaška Malého, na francouzskou kamarádku Mariánku Canavaggio, na Alenku Kumprechtovou. Nebo na paní, která s námi bydlela v rozděleném bytě. Nebyla součástí disentu, ale všechny nás milovala. Květa i Alenka byly součástí disentu, ale dneska je nikdo nezná. Lidi mají představu, že všichni disidenti dostali funkce nebo se někam zařadili, ale většina z nich má sociální problémy a nízké důchody, protože před revolucí nevydělávali a ani potom neměli žádnou extra práci, protože třeba nevystudovali. Byli to především fajn lidi, úplně normální. Pamatuji si samozřejmě i Havla, ale moje primární vzpomínka je, že se jednalo o namíchanou společnost lidí z různých prostředí, kterým vadilo to, co bylo.

» Proč se řada disidentů po revoluci dál veřejně neangažovala?

Jednak proto, že už dál neměli tu potřebu – začali žít ve svobodné společno sti a problémy, které máme dnes, vidělo přicházet jen velmi málo lidí. A druhá věc: zapojit se v novém režimu vyžadovalo přece jenom ostřejší lokty. Do té doby stačila statečnost – někam jít, něco podepsat, přepsat, odnést – a člověk toho byl součástí. Ale aby se člověk nechal zvolit nebo jmenovat, k tomu potřeboval už trošku jméno, doporučení a ambice.

» Jak sis poradila s neoficiálním světem doma a tím, cos zažívala třeba ve škole?

Doma se mluvilo naprosto otevřeně. Rodiče mě nikdy nevedli k tomu, abych kontrolo vala, co říkám. Ale tušila jsem, že něco se ve škole říkat nemá. Někteří mí spo lužáci ani nevěděli, že žijí v nesvobodném režimu, že existují disidenti, kteří jsou třeba i ve vězení. Když se mě ve škole ptali, co dělá můj táta, a já řekla, že je ve vězení, spolužáci si mysleli, že spáchal nějaký trestný čin. Ale sympati zovala se mnou jedna učitelka. Když jsme měli domovní prohlídku, chápala, že jsem přišla do školy později. Jako dítě jsem žila relativně ve svobodě.

4 5

*1977, Praha, Československo, dnes Česko novinářka, romistka

Saša Uhlová Zbigniew Libera Zuzana Mistríková Aleš Palán Antonina Krzysztoń Vladimír Michal Věra Roubalová Kostlánová Andrzej Jagodziński Tereza Nvotová Miloš Rejchrt Dorota Masłowska Peter Kalmus

4 12 18 24 29 32 37 44 50 57 63 66

Saša Uhlová

Vnímáš dnes slovo svoboda jinak?

Teď už má pro mě mnohem širší obsah. Tehdy pro mě svoboda znamenala svobodu slova a pohybu. Vnímala jsem, že člověk nesmí říkat, co chce, a může být omezený na svo bodě – zavřený ve vězení nebo nemít možnost cestovat. Ale s bráchou jsme dva roky před revolucí za hranice mohli! Jeli jsme sami, mně bylo jedenáct, jemu třináct. Rodiče pas neměli, ale když se režim trochu uvolnil, nám s bráchou ho dali, a tak jsme byli nejdřív ve Francii a potom v Sovětském svazu, v Litvě, v Estonsku, v Lotyšsku a nakonec v Polsku. Jet se podívat za hranice pro mě byl formativní zá žitek. Uvědomovala jsem si, jaké máme štěstí. Bylo mi jasné, že až vyrostu, nebu du moct nikam, protože se zapojím do hnutí a pas mít nebudu. Když jsem se vracela z Francie, brečela jsem, protože jsem si myslela, že je to naposledy. Nemohli jsme tušit, jak to bude dál. Tehdy jsme nasedli do přímého vlaku do Paříže, za hranice mi začal průvodčí rozdávat Tigridovo Svědectví a ve Francii si nás pak předávali různí lidé, většinou Francouzi, ale chvilku jsme byli i u Pavla Tigrida a Ivanky Tigridové, taky u nějakých soudruhů ze Čtvrté internacionály…

» A co cesta do Sovětského svazu?

Na východě to bylo drsné. Jeli jsme do Petrohradu k mamince máminy kamarádky Iriny, která dělala v Akademii věd. Máma tam pracovala taky, ale myla laborator ní nádobí, doma jsme jí říkali „myčka akademička“. Irina byla z Petrohradu, ale v Československu se zapojila do disentu. Její maminka byla taky vědkyně, ale hodně bláznivá. Problém byl už v Praze na letišti, kde nám vzali kufry a prohlíželi věci. Naši po nás samozřejmě nic neposílali. A pak v Petrohradě nás Irinina máma odvedla do svého bytu, dala nám klíče, řekla, že bude chodit do práce, že si máme udělat kafe, a tím to skončilo. Brácha byl hodně činorodý, tak nás odvezl na jezera někam za Petrohrad, přes která jsme plavali, nebo jsme chodili po petrohradských ulicích a jedli v místních jídelnách. Byl to blázinec, ale dobrý. V pobaltských republikách se o nás starali nějací příbuzní. A Polsko? Táta měl Východoevropskou informač ní agenturu a každou středu večer volal dvě hodiny do Polska. Když jsem potom před revolucí seděla v Polsku na srazu s mladými lidmi, normálně jsme se bavili a rozu měli si. Vyprávěli mi třeba, že mají nedostatek zápalek: musejí čekat, až si někdo bude chtít taky zapálit, aby škrtli sirkou jenom jednou. Nás se zase ptali na útlak policie, co se může, co ne. Vyrozuměla jsem z toho, že v něčem mají trochu větší svobodu než my. V roce 1988 jsem Polsko dokonce vnímala trošku jako Západ, tak sil ný zážitek to pro mě byl. Chtěli jsme tam jet ještě na začátku listopadu 1989 na koncert, ale vyhmátli nás, vysadili z vlaku a museli jsme zpátky. Máma nás tehdy pustila. Byla jiná doba, já bych to s mými dětmi nedala. Ale my jsme byli s bratrem hodně samostatní.

Po Československu je pro mě Polsko nejbližší zemí, dokonce tam máme s Alarmem (levicově orien tovaný internetový deník) sesterský projekt – Krytyku Politicznu, kam přeložili moje reportá že. Mě samotnou polská reportážní škola velmi inspiruje. V souvislosti s Polskem ještě musím zmínit Dádu Fajtlovou, za kterou jsme jako děti jezdili a potkávali u ní Poláky, a Pomezní Boudy, kde se scházela Solidarita. I k nám domů jezdili Poláci, třeba Jacek Kuroń.

» Máš sama čtyři děti. Přemýšlíš někdy nad tím, jak to s vámi tvoje máma před revolucí zvládala?

Jako dítě jsem nikdy nepochybovala o tom, že až vyrostu, budu součástí disidentského hnutí, zavřou mě do vězení a nebudu studovat. Vyrůstala jsem v tom a byla s tím ab solutně smířená. Ale když se mi narodily děti, najednou mi došlo, že vůbec nevím, jak bych zvládala představu, že by mi je někdo odebral. Trpím tím – i když vím, že žiju ve svobodné společnosti, kde se děti odebírají „jenom chudým lidem“ –, přestože mám nejlepší možné rodinné zázemí a právníky v rodině. Kdyby hrozilo, že mi děti odeberou, byla bych ochotna se prostřílet na hranice. Věděla jsem, že do KSČ bych kvůli dětem nikdy nevstoupila. Tak by nemohly studovat. Navíc se člověk vždycky může vzdělávat někde vedle. Do KSČ bych nikdy nevstoupila ani kvůli práci. Spíš bych s oh ledem na děti zvažovala, do jaké míry se zapojit do disentu, protože bych se bála.

» Jsi člověk schopný emigrace?

Možná je to jen kolektivní úzkost, ale svět stojí před změnou, i kvůli klimatu. Stát se může cokoliv: v Evropě nastoupí nějaká podoba fašistického režimu, EU se rozdělí a my budeme ve sféře vlivu Východu, zvedne se vlna z Afriky a půjde na Evropu… A buď

bude potřeba odejít, anebo bojovat. Kvůli dětem bych měla plán odejít, ale zřejmě bych nakonec zůstala. Asi bych neodjela včas, protože by se mi nechtělo.

» Vidíš budoucnost spíš v menších územních celcích a komunitách, nebo ve větší integraci v rámci Evropy?

Myslím, že cesta je obojí – mít velký územní celek s ústavou, definovanými lidský mi právy a zřejmě i restriktivními pravidly ohledně životního prostředí, a zároveň věci dělat zespodu. Povahou jsem spíš komunitarista, zároveň bych chtěla mít nad sebou nějakou střechu. Za Evropskou unii jsem vděčná, v určité podobě by měla pře trvat. Vždycky si vzpomenu na boj za rovnoprávnost v Americe, jak federál pomáhal proti místním rasistům a Ku-klux-klanu. I seshora může přijít dobro!

Nebo dám příklad oddlužení. V České republice je koncem roku 2 18 skoro devět set tisíc lidí v exekuci, která se ale týká i jejich příbuzných, tedy až dvou a půl milionu lidí. O co jde, můžou vědět na Slovensku, v Polsku, na Balkáně, ale Západu nedokážeme vysvětlit, co se tady stalo. Mnohačetné exekuce byly často bagatelními dluhy, tisícovkami, ze kterých vyrostly dese titisíce, statisíce. Stal se podvod na lidech, měl složité příčiny, od blbých zákonů po lidi, kteří je zneužili a rozdělovali pohledávky, co pak šly různým exekutorům. Na Západě je možnost oddlužení do tří, maximálně pěti let, aniž by člověk částku splatil. U nás se změnil zákon, člověk musí splatit aspoň třicet procent částky; neplatí však dluh, ale příslušenství k němu. Pokud nevystoupíme z EU, jejich jasná a rozumná pravidla nakonec přijmeme taky. Média do EU ale pořád šťourají, navíc jde často o hoaxy. EU přinesla spoustu dob rých opatření, ze kterých profitujeme, a vůbec si neuvědomujeme, že je máme díky ní, za peníze, které se do Česka nalily. To, že jsme si takto získané peníze čás tečně rozkradli, je věc jiná, to není chyba EU.

Umím si představit budoucnost s lokálními měnami, které bude zastřešovat euro, návrat lidí k půdě a životu v menších komunitách. Ale třeba to bude s klimatickou změnou fičák a nebude čas nic vymýšlet.

» Bojíš se, že budou chtít Češi vystoupit z EU?

Toho se bojím, ale zatím si myslím, že by pro vystoupení nehlasovali. Mám však strach z ruské propagandy, aniž bych chtěla nějak přeceňovat její vliv. Rusko mám ráda, ale teď mluvím o ruské politické garnituře vypouštějící dezinformace. Čím dál častěji se setkávám s tím, že i lidi celkem příčetní opakují vážně a přesvědčeně zjevné nesmysly.

» Díky projektu Hranice práce, kdy ses inkognito nechala zaměstnat v nejhorších možných, přitom ale velmi užitečných pracích, se ti podařilo protlačit velké sociální téma – nejhůře placenou práci – na evropskou úroveň. Byl to zázrak. Když jsem na projektu dělala, vůbec mě nenapadlo, co nastane v České republice, natož jinde. Už několik měsíců poskytuji dva rozhovory denně, byla jsem ve všech českých médiích, lidi mě poznávají na ulici. I když jsem unavená, pořád všude chodím a téma pracovních podmínek tlačím. Měla jsem problém sehnat lidi, kte ří by mi neanonymně vyprávěli o svých pracovních zkušenostech, a tak jsem se roz hodla, že se nechám sama zaměstnat v různých špatně placených, nekvalifikovaných profesích a napíšu o tom sérii textů. A pak se dokumentaristka Apolena Rychlíková rozhodla o tom natočit film. Koupila jsem si speciální brýle a práce začala natá čet tajnou kamerou, vedle série textů a filmu jsem nakonec vydala i svůj deník z té doby. O pracovních podmínkách v Česku se začalo konečně mluvit a možná se i troš ku posunul diskurz. Když dneska někdo řekne, že je v odborech nebo že se porušují pracovní podmínky třeba nedodržováním zákonných pauz, zní to jinak než před dvěma lety. Není to jen mnou – máme dobrého šéfa odborů, který jede kampaň „konec lev né práce“, taky se láme doba a po třiceti letech od revoluce se o takových věcech konečně začíná mluvit. Já jsem k tomu přispěla i tím, že jsem vrátila do české aktivní slovní zásoby výraz vykořisťování. Smála jsem se, když na festivalu doku mentárních filmů v Jihlavě udělila komise Apoleně cenu za film s odůvodněním, že natočila Sašu Uhlovou, která „neideologicky podává zprávu o vykořisťování“. Ještě před pár lety bylo slovo „vykořisťování“ vnímáno jako silně zatížené ideologií.

Po filmu a článcích se také zvyšuje minimální mzda, a to hodně. Předtím se několik let nezvý šila vůbec, zvyšovat ji najednou je problematické, ale musí se to dohnat. Když má člověk šest a půl nebo sedm tisíc čistého, pokoj v sídlištním bytě si z toho zaplatí, ale už se nenají.

A co se týká pracovních podmínek, hodně věcí je daných tím, že se dějí protizákonně. Inspekto rát práce může přijít na pracoviště a ptát se lidí, ale oni mu nic neřeknou, protože se bojí.

6 7 »

Saša Uhlová

Saša Uhlová

A ti, co si na inspektorátu práce stěžují, zas nemají důkazy, jsou osamocení. Cesta ke změně je v kolektivním vyjednávání, kolektivně se lidi bát nebudou.

A v Evropském parlamentu jsme se s Apolenou snažily vysvětlit mzdovou železnou opo nu a to, že nižší mzdy na Východě můžou být jedním z důvodů rozpadu EU, protože lidi budou jen těžko solidární, pokud budou mít pocit, že EU není solidární s nimi.

A v Česku speciálně. Když pak někdo řekne, že k nám přijdou uprchlíci a budeme se muset dělit, přichází to do kontextu lidí, kteří jsou v exekuci nebo mají obavy o budoucnost, a to nedělá dobrotu. O mzdách by se mělo mluvit vážně, a právě na ev ropské úrovni. Jestli to tam od nás ale někdo slyšel, to nevím. » Jak Západ vnímá Českou republiku, respektive celý náš region?

Protože jsem pět let po revoluci studovala ve Francii, jsem už na všechno zvyk lá. Francouzi tehdy neznali rozdíl mezi Československem a Jugoslávií, ptali se mě, jestli je u nás válka. Teď už je to lepší a i v Bruselu o nás nějaké ponětí je. Vnímám ze strany Západu vůči nám jistou blahosklonnost – ne že bychom tady po dle nich byli úplně zaostalí, ale i vinou toho, co se teď u nás děje a jak se naši představitelé chovají, cítím mírný odstup. V horším případě je to nezájem a před stava, že kdyžtak odpadneme, v lepším případě snaha, aby se tak nestalo.

» Máme vůbec šanci dostat se do role významného evropského partnera, jakým je Německo nebo Francie?

Myslím, že ano. Geograficky k tomu máme docela dobrou dispozici. Ale hodně věcí jsme posrali tím, že ze strachu, abychom znovu neměli komunismus, jsme neregulovali věci, které se na Západě normálně regulují. Spousta podnikavců toho zneužila a hod ně lidí se dostalo do problémů typu nesplatitelné dluhy. Zároveň u nás ještě re lativně hodně věcí funguje – v Česku je bezpečno, ve srovnání s jinými zeměmi máme fungující dopravu, dráhy, poštu, i když i tu se snaží někdo vytunelovat a zpriva tizovat. Ještě tak mít kompetentní vládnutí, což opravdu není Babiš, který myslí primárně na sebe, mohli bychom se mít ekonomicky mnohem líp. Měli bychom se snažit transformovat ekonomiku založenou na levné práci na inovace a jít jinou cestou, tím bychom se mohli stát zajímavou výspou Východu. Nechci přivolávat nějaké dělení, ale myslím, že kdyby na to došlo, lidi by se rozhodli pro Západ. Díky tomu, že máme se Západem společné hranice, máme – na rozdíl od jiných zemí dál na východ – možnost volby. Možná se o to teď zrovna hraje.

» Můžeš se pokusit i o malou reflexi Slovenska a Polska?

Globálně to asi nedokážu, ale na Slovensku jsem před časem psala větší reportáž o tamější politické situaci a přijde mi, že jejich takzvaná elita je na tom podobně bídně jako ta naše. Elity mají představu, jak by „to“ chtěly, ale nejsou napojené na lidi, neumějí najít jejich jazyk. Slováci demonstrují za předčasné volby, ale nemají žádnou stranu, která by měla šanci dostat se do parlamentu. A to je problém, něco vyvolat, ale nebýt schopen to politicky proměnit ve výsledek. Dvě pidi stra ničky mají dohromady dvě procenta a ještě se hádají. Ale mění se to. Lidi chodí de monstrovat a tlakem jsou schopni udělat ve vládě alespoň nějaké změny, sami na to ale politicky nemají. Je to podobné jako v Česku – jde se emotivně demonstrovat na náměstí, ale už se nevolí další politické cesty, politika tak běží dál a ne vždy dobře.

A Polsko? Miluju Polsko liberální. Demonstrace v Polsku jsou ohromné. A pak je Polsko konzer vativní – jestli ho takové většina společnosti chce, mrazí mě z toho. Konzervativismus jako takový mi nevadí, ale pokud se zákony snaží život ušroubovat ze všech stran, přijde mi to ne mocné, třeba u potratů. Ať se dělají restrikce, potratové komise, všechno si umím představit, i když si nemyslím, že je to cesta. Ale některé věci mi už přijdou za hranou a bizarní, třeba že nárok na intelekt mají mít jen kluci. A hledám ještě jiný pojem než „konzervativní“, protože konzervativismus může mít normální lidskou podobu. Já jsem vlastně taky konzervativní – když jsem měla malé děti, nechodila jsem do práce, protože si myslím, že by děti měly být s jednou pečující osobou. Dnes jsme se všichni nechali zahltit prací, přitom bychom se měli vracet k rodině. Ale slova, která padají z některých „konzervativců“, ať už xeno fobních hnutí nebo „staré levice“, mi přijdou blízká neonacismu, krajní pravici, podobné islámskému fundamentalismu! Ano, dnešní svět ohrožuje fundamentalismus.

» Co klerikalismus?

V Česku je to spíš antiklerikalismus. Asi bych opravdu používala slovo fundamenta lismus. Ale ano, často je klerikální, na Slovensku, v Polsku, v islámských zemích, jen ateistické Česko to má jinak.

» Mimochodem – věříš ještě v rozdělení levice a pravice?

Na festivalu v Jihlavě teď proběhla debata o budoucnosti levice, kde jsem si znovu uvědomila, že levice má smysl. Je založena na ideálu rovnosti, solidarity a svobo dy, která má jiný význam než v konzervativním nebo neoliberálním pojetí. Pro nás je svoboda i to, že lidi můžou žít důstojně. Bydlet pod mostem a mít hlad není v na šich očích úplně projevem svobody. I svoboda vyžaduje nějaký standard, aby ses mohl rozhodovat. Ale levice dnes selhává, proto ji tolik lidí opustilo.

» V Česku je dnes přetlak stran na středu. Jak lidi volí?

Emotivně, ale to volíme asi všichni, jen někdo si volbu ex post vysvětluje racionál ně. V knize Hrdinové kapitalistické práce mám rozhovor s vysokoškolačkou z Ostravy; ptám se jí v něm, proč volí Okamuru. Říká, že je větším vlastencem než spousta Čechů a že jsou její táta a děda zblblí Českou televizí, proto volí Babiše, kdežto ona si hledá zdroje na internetu. To je nebezpečné.

» Jaká další nebezpečí ohrožují demokracii?

Podle mě je problémem kapitál. Ano, je to levičácká odpověď, ale současný stát tře ba není schopný plnit jednu ze svých základních funkcí – vybírat daně. Stále exi stují daňové ráje, kdy sice firma odvádí daně z příjmu v Česku, ale zisk se nedaní nikde, čímž uniká spousta peněz, které pak jinde chybí. To, že ani mezinárodní spo lečenství s tím nebylo schopno nic dělat, podkopává důvěru lidí ve stát, protože vidí, že velké peníze někam odcházejí a bohatí si můžou dělat, co chtějí.

A pak je tu další věc – abys dnes vyhrála volby, musíš mít peníze. I když máš stranu plnou zajímavých lidí, bez peněz je těžké vyhrát, může se to povést jen náhodou. Marketing, volební kampaně i rozhodnutí politiků jsou často ovlivňována lobbisty a úplně se ztrácí to, že jdu volit nějaké ideje a lidi, kteří je zastávají, pak hlasují o úroveň výš v můj prospěch. Pak se jen domýšlím, jak je možné, že moje strana pro něco hlasovala, a jako občan ztrácím pocit, že žiju v demokracii, a nabývám dojmu, že tu místo politiků vládne někdo jako Kellner. Proto je výzvou umět zkrotit velký kapitál, nastavit kontrolní mechanismy. Nemám moc ráda Piráty, protože podle mě nemají žádné ideologické podhoubí, ale prý s nimi kvůli tomu, že si o všem dělají zápis, nejednají lobbisti, takže teď se STAN, Janem Čižinským a Katkou Valachovou hla sovali pro dobré změny v zákonech. Pirátům se povedlo nastavit si ve straně vnitřní mecha nismy vůči kapitálu a to je demokratické – člověk si je zvolil a oni skutečně fungují tak, jak slíbili. V jiných případech může mít volič pocit, že nemá vliv; ztrácí naději a obrací se k radikálním řešením.

Revoluce totiž zákonitě vynáší nahoru lidi, kteří se měli dobře i předtím, a proto jsem proti ní. Lidi po roce 1989 přeměnili sociální kapitál na ekonomický, což je v podstatě charakteristikou revoluce – dějí se rychlé změny, je v tom chaos a naho ru se derou ti, co to v politice už umějí. Pokud chceme změnit společnost, musíme paradoxně rezignovat na revoluční změny a velmi jasně diskutovat – třeba jako ve Švýcarsku, kde se konají diskuse a potom referenda. Potřebujeme dělat změny postup né, které zkrotí ty, kdo se chtějí obohacovat na úkor ostatních, a to na principu vzdělané, informované společnosti.

» Jako dítě ses chtěla angažovat. Co dnes? Plánuješ vstup do politiky?

Jako malá jsem chtěla být prezidentkou, což mi vydrželo i nějakou dobu po revoluci. V devatenácti jsem chtěla vstoupit do sociální demokracie, ale nechtěli mě. Potom jsem byla dva roky ve Straně zelených, kde jsem pochopila, že nejsem člověk, kte rý by mohl dělat politiku. Jsem poměrně dobrá pozorovatelka, ráda píšu, ale nerada něco organizuju, nebaví mě dělat volební kampaně, někoho přesvědčovat. Vlastně je mi to protivné. Poté, co jsem prošla mediální smrští ohledně Hranic práce, lámali mě do senátních voleb tady na Praze 2 a 3. V tu chvíli by byla velká šance se do Senátu dostat, lidi mě mají poměrně rádi, byl by to pěkný džob, měla bych hodně pe něz a nemusela bych ani moc chodit do práce. Zároveň bych ale nemohla dělat to, co

8 9

Saša Uhlová

Saša Uhlová

chci – psát. A tak jsem řekla ne. Můj táta má na takové věci buldočí povahu, já mám ale práci a rodinu a víc toho nezvládnu.

» Jako novinářka ovšem také máš značnou moc nastolovat témata.

O tom se vede debata. Směju se novinářům, kteří říkají, že jenom informují. Při tom už jenom tím, že do novin témata vybírají, určují, o čem se bude mluvit. Vedle zpravodajství navíc existují reportáže, názorové texty, takže říkat, že jenom in formuji, je pokrytecké.

» Má být práce žurnalisty angažovaná?

Ve Francii jsme vedli debatu, jestli má být angažované umění. Myslím si, že umění, které není angažované vůbec, není uměním. Ale když angažovanost přesáhne určitou míru, půjde o propagandu. Přečtu ti citát od Mileny Jesenské: „Úloha reportéra se někdy podobá úloze hyeny. Obchází s notýskem a zapisuje lidské útrapy, aby je sdě lil novinám. Kdyby to dělal bez jiskřičky naděje, že jeho vytištěná slova pomohou, nestál by ani za podání ruky. Pro tuto naději se omlouvám všem, které jsem v po sledních dnech vyhledala v jejich brlozích, za zvídavost mého vyptávání, jež muselo být bolestné a dotěrné. Musela jsem jim nutně připadat jako člověk z druhého, bez pečného břehu, který zapisuje s tužtičkou v ruce míru jejich strádání. Stála jsem před nimi zahanbena, neboť mne očekával vlídný domov, práce a zítřek. Otřese-li se však jednou půda mého domova ničivým výbuchem, jako se otřásly domovy jejich, bu deme pak pravděpodobně stát všichni proti společnému nepříteli – a doufám, že se znovu shledáme.“ Milena Jesenská tím říká, že novinařina je povoláním, a když ně kdo tvrdí, že není, asi to dělá jen pro peníze. Já se k psaní cítím povolaná. Možná proto nemůžu být senátorkou, i když by to bylo pohodlné.

» Pověz mi ještě něco o své inklinaci k levici.

Jednak jsem z rodiny, kde se všichni definují levicově, takže jsem vyrůstala v tom, že být levicová je normální. Pak přišla revoluce, ve společnosti se všechno zamí chalo a já jsem zažila ohromné problémy s okolím i kamarády, kteří začali říkat, že jsou pravicoví. V sedmnácti jsem odjela studovat do Francie, kde jsem byla s le vičáctvím zase „normální“ – tehdy tam pravičáctví moc cool nebylo, dneska už je to jinak. Po návratu to zas bylo těžké, ale se vznikem Deníku Referendum jsem zjisti la, že levicově smýšlejících lidí jako já je víc. Dnes už se dá hovořit o komunitě lidí, se kterou se zase navštěvujeme, děláme večírky, jen nežijeme v disentu a dou fám, že ani nebudeme. Myšlenkově jsme napojeni na Západ, kde přemýšlení o budouc nosti patří levici. Pro mě je levice jediným možným východiskem. Určitě existují hodní pravičáci, ale na pravici podle mě není intelektuální síla a chuť o věcech přemýšlet. Levice jde sice často do slepých uliček, plete se, ale nekontrolovatelný kapitalismus vede k autoritářským režimům. My musíme vymyslet, jak se vymanit z ne ustálých krizí.

» Vnímají Češi vůbec dělení na pravici a levici správně?

Někteří čeští pravičáci by byli na Západě levičáky, kdybychom neměli v Česku his torii, jakou máme. Proto si s některými pravičáky tak dobře rozumím a v hospodě se neshodneme jenom na minimu věcí. Někdy si o mně lidi myslí, že jako levičák některé věci neříkám nahlas, ale tak to není.

» Jaký je stav české žurnalistiky?

Problém je v tom, že si někteří čeští novináři myslí, že se objektivita jednoduše zajistí poskytnutím prostoru oběma stranám sporu. Jako by byly jenom dvě… Ale já jsem antropoložka a vím, že do situací vcházím s balíčkem svých zkušeností, idejí, předsudků, a tím pádem vidím jiné věci než někdo s jinou životní zkušeností, který pak napíše úplně jiný text. Neznamená to, že horší, ale je dobré reflektovat vlastní ideologické postavení. Bohužel v Česku tahle reflexe schází.

Když jsem šla dělat Hrdiny kapitalistické práce, přemýšlela jsem o tom, že mám ze svých ide ových pozic a priori předsudek vůči zaměstnavatelům. Nakonec je v knize podkapitola o dobrém zaměstnavateli, ale uvědomovala jsem si, jak to nechci vidět. Mohla jsem to vypustit, vytěs nit. Ale nad věcmi je třeba přemýšlet ve smyslu, že všichni jsme v zajetí ideologických před

sudků a představ. Když s tím člověk nepracuje, závěrečná zpráva je plošší nebo ideologičtější. A rozhodně není nikdy nic objektivní. Člověk může směřovat k většímu nadhledu, ale jedině za předpokladu, že si uvědomuje, kde stojí. To české žurnalistice chybí.

» Pověz mi jako antropoložka a romistka, jestli se za třicet let nějak změnilo postavení Romů v Česku.

To je velké a složité téma, ale ve zkratce: Romové transformaci nevyhráli, jejich sociální propad měl řadu příčin. Kvůli restrukturalizaci průmyslu hromadně při cházeli o práci, často se nechali napálit, přicházeli i o bydlení, spousta z nich ztratila rozdělením Československa české občanství, a tím pádem u nás nedosáhli na žádné dávky. S desetitisíci lidmi bez občanství samozřejmě přišla řada problémů. Zároveň se svobodou se objevily neonacistické skupinky, v devadesátých letech do cházelo k častému napadání Romů. V té době jsem neznala romskou rodinu, kde by ně koho nenapadli. Romové přestali chodit do kina, do hospody, nevycházeli ven, když byl fotbal. Úplně se jim změnil život. Po protiromské vlně se to v roce 2 8 trochu zlepšilo. Romové začali odcházet do Kanady, republika pro ně spustila různé pro gramy. I v televizi se o nich začalo mluvit jinak. Ještě v devadesátkách zaznívaly v televizi strašlivé věci, třeba při debatách se Sládkem, nebo se dával prostor li dem z ulice, kteří říkali ty úplně nejhorší věci. Když pak přišli uprchlíci, hodně Romů se mě ptalo, jestli je dočasné, že si jich Češi přestali všímat, anebo se to zase vrátí. Odpovídala jsem, že se bojím, že uprchlíci nepřijdou a Češi zas budou mít potřebu něco vytáhnout. Bylo to vidět teď před volbami. Východisko ze situa ce vidím u Romů víc v etnické emancipaci, přestože problémy jsou sociálního rázu a taky je třeba je tak nazývat. Ale taky je tu diskriminace a hrdost Romů, která jim může dodat sílu něco dělat.

» Je ke změnám ve společnosti nutná spíš změna systémová, nebo změna mentálního nastavení jednotlivců?

Myslím, že v této chvíli je u nás v Česku nutná změna mentální. Žádné segregační zákony tu nemáme, většina věcí se odehrává na úrovni mentální. Typický problém se školou je ten, že ředitel nemusí být rasista a může umět pracovat s předsudky, ale ve chvíli, kdy se mu ve škole změní poměr romských dětí, bílé mu začnou odcházet a škola se stane segregovanou. Ředitelé si musejí hlídat poměr, ale zároveň to ne znamená, že nepřijmou žádné romské dítě. Optimální je mít ve třídě dvě tři romské děti, aby to bylo stejné jako v populaci.

» Které tuzemské události tě nejvíce ovlivnily?

Klíčový byl pro mě samozřejmě rok 1989, hodně se toho změnilo i v rodině. A pak rok 2 11, kdy probíhaly demonstrace ve Šluknovském výběžku. Viděla jsem lidi –o kterých si nemyslím, že by byli ve své podstatě zlí – jak se snažili dobýt kame ny ubytovnu, kde byly romské děti. Když jsem pak s nimi mluvila, ukázalo se, že je trápí úplně jiné věci než Romové. Mimo jiné to, že jim nikdo nenaslouchal! Seděla jsem s nimi několik hodin a poslouchala, že jsou nezaměstnaní, bez práce nemají na nájem, na radnici je korupce, zrušili jim místní školu, prostě začala smršť lo kálních problémů, která končila tím, že Praha na ně zapomněla. Ukázalo se, že po kud periferie nezvedne cikánskou kartu a nebude rasistická, Praha si jí nevšimne. Romové se tak stali komunikačním kanálem mezi periferií a centrem. Když jsem viděla lidi připravené rozpoutat pogrom, uvědomila jsem si, že se to může stát znovu. Byl to pro mě mezník. Začala jsem být depresívní a přestala si být jistá, že ve svo bodné společnosti už budeme žít navždy.

» Kdo myslíš, že je schopen větší reflexe demokracie – přímí účastníci sametové revoluce, anebo naopak úplně mladá generace?

Myslím, že mladé generaci půjde reflexe snáz, protože není zatížená chybami, kte ré se udály. Některé situace neměly daleko ke komunistické propagandě, byly jen s opačným znaménkem, což si ale někteří lidi nikdy nepřiznají.

» Vyprávěj mi prosím ještě své zážitky z doby revoluce.

Demonstrace byly celý listopad. Pamatuji si, že na nás mířili vodním dělem a bráchu trefili. Mně se vždycky povedlo utéct, nikdy se mi nic nestalo, ani teď na demon stracích, kde fotím, se nedostávám do konfliktů. Umím se v tom pohybovat. Rodiče

10 11

Saša Uhlová

Saša Uhlová

nás nechávali na demonstrace chodit. Venku jsme se s bráchou pohybovali sami od osmi let, doma jsme se neptali, jestli můžeme jít. Demonstrace nás zajímaly, přišlo nám to vzrušující. Máma chodila někdy, táta ne. Hlídala je policie, máma musela přelézat plot a táta říkal, že je to pod jeho důstojnost, že bojuje jinak. A pak přišla demonstrace na Škroupově náměstí, která byla povolená, lidi nikdo neroz háněl, mohli vystoupit s projevy. Revoluci jsem přicházet neviděla, pamatuju si jen, že když padla berlínská zeď, máma se rozbrečela. Ptala se, kdy to přijde sem; vypadalo to, že snad nikdy.

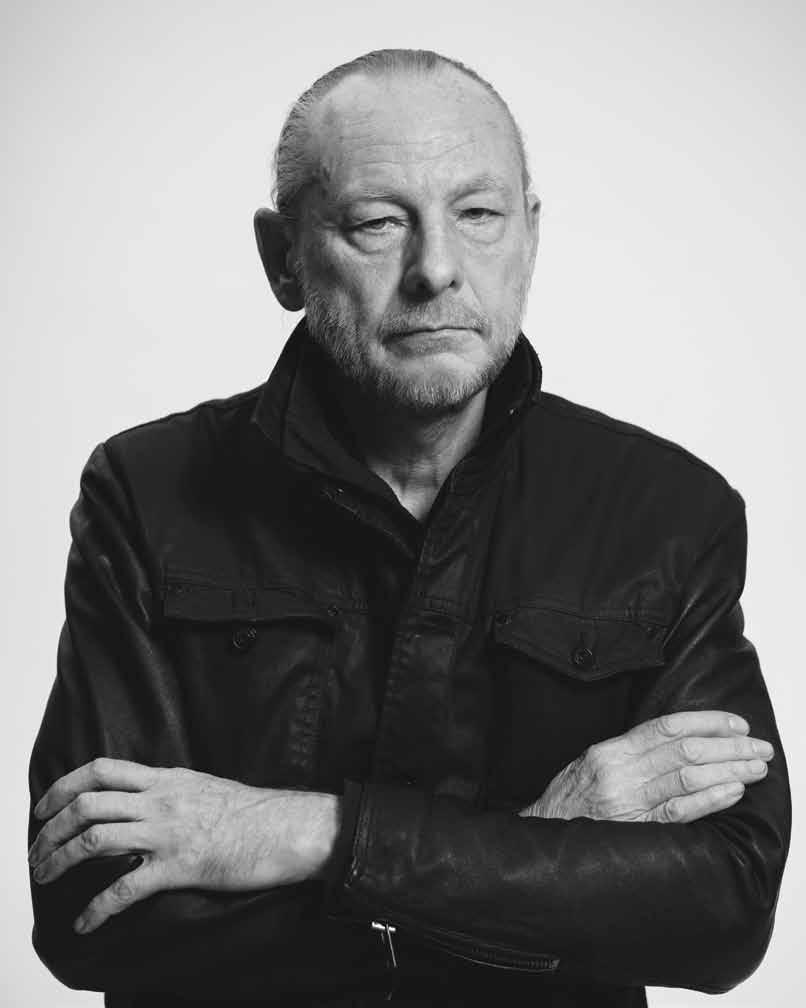

Zbigniew Libera

» W latach osiemdziesiątych wylądował pan za zaangażowanie społeczne w więzieniu. Jak takie przeżycie formuje człowieka?

Zasadniczo mnie ukonstytuowało. Zanim poszedłem do więzienia, nie wiedziałem, jaki jest świat naprawdę. Miałem dwadzieścia lat, a tacy młodzi ludzie prawie nic o świecie nie wiedzą, chyba że pochodzą z rodzin traumatycznych. Ja pochodziłem z drobnomieszczaństwa, mama była pielęgniarką i wychowywała mnie samotnie – ojciec zmarł, kiedy miałem trzy lata. Do więzienia trafiłem, bo uważałem, że się trze ba zaangażować, i drukowałem ulotki. Więzienie jest twardą szkołą życia. Albo się przeżywa, albo nie. Jest rzuceniem człowieka na głęboką wodę. Raz zachorowałem i nie chcieli mnie leczyć. Lekarz zapytał tylko o nazwisko i od razu mnie odesłał z powrotem. Poprzez kontakt z księżmi, którzy odprawiali w każdą niedzielę mszę w więzieniu, dałem informację do matki, która dostarczyła mi leki, ale w międzycza sie już miałem zapalenie płuc i w malignie niesamowite wizje, że jestem w teatrze, nagle kurtyna się podnosi i widzę, czym jest teatr rzeczywistości. Wówczas przesta łem się bać. Na wolności człowieka straszą, że pójdzie do więzienia, ale jak już tam jest, więcej nie ma go czym straszyć.

Najpierw siedziałem w więzieniu kryminalnym, bo w socjalizmie oficjalnie więźniów politycz nych nie było. Musieliśmy to sobie wywalczyć. Dopiero po pięciodniowej głodówce przewieziono mnie wraz ze starszym kolegą Longinem Chlebowskim, przywódcą strajku tramwajarzy łódzkich, do więzienia dla więźniów politycznych. W normalnym więzieniu najpierw rysowałem długopisem albo ołówkiem na prześcieradle dla więźniów, którzy przynosili zdjęcia swoich narzeczonych. A póź niej prosili o tatuaż. Do tej pory nigdy tatuaży nie robiłem i nie miałem pojęcia, jak się je robi. Jeden więzień kryminalny, który miał przynajmniej ze trzynaście lat siedzenia przed sobą, zamówił wielkiego amerykańskiego sokoła na brzuchu. I tak zacząłem ćwiczyć. Jedzenie podawane w więzieniu było okropnie świńskie. Dorosłemu człowiekowi, mającemu powyżej dwudzie stu jeden lat, przysługiwał raz w miesiącu kawałek mięsa (tłuszczu ze skórą jeszcze z włosiem) o wielkości paczki papierosów. To mięso wykorzystywałem do ćwiczeń. Zastanawiałem się, jak zrobić sokołowi pióra, a starsi więźniowie powiedzieli mi, że istnieje technika zwana „moj ką”, czyli żyletka, którą można zrobić delikatne i cienkie nacięcia, i do nich wetrzeć tusz. Zacząłem pracę, ale to okropna technika – codziennie da się zrobić kwadracik trzy na trzy centymetry, bo już w trakcie robienia zaczyna skóra puchnąć i czeka się, aż zejdzie strupek i opuchlizna, i dopiero się dzieło dokańcza. Po kilku miesiącach zrobiłem więźniowi pół so koła i wyjechałem do innego więzienia. Na szczęście nigdy już tamtego więźnia nie spotkałem. Byłem też wielokrotnie przenoszony karnie z oddziału na oddział, z bloku na blok, na przykład za kolportaż tygodnika Osservatore Romano. Raz trafiłem do celi, gdzie siedziało trzech mało letnich więźniów i siedemdziesięciopięcioletni zawodowy bokser, na którym owa trójka próbowała wymóc, żeby się dostosował do ich zasad grypsery – języka, rytuałów. Bokser walczył w drugiej wojnie światowej, był żołnierzem w armii angielskiej generała Maczka, i teraz miał się dosto sować do więźniów w celi? Był tam potworny konflikt, okropna atmosfera. Mnie tam wrzucili, żebym stanowił pewnego rodzaju przegrodę. Żeby przeżyć i mieć spokój, musiałem między nimi negocjować. W końcu ze wszystkimi się zaprzyjaźniłem. Pan bokser opowiedział mi całe swoje życie, a o małoletnich dowiedziałem się, że byli chłopcami z fatalnych rodzin kryminalnych, którzy krzyczeli i rozrabiali, ale tak naprawdę tęsknili za ciepłem, miłością, jakimś tatą czy

starszym bratem. Przeprowadzanie negocjacji było niesamowitą szkołą postępowania w konflikcie. I zaliczam to do dyscypliny artystycznej. Potem już nie bałem się o nic, nawet o swoje życie.

» Co dla pana znaczy wolność? Czy według pana ma jakieś granice?

Granice są proste. W celi z okropnymi przeciwnościami można się granic nauczyć –rób wszystko w ramach tego, żeby nie krzywdzić, nie urazić, nie szkodzić. Jak tego będziesz przestrzegać, możesz mieć wolność. Absolutna wolność nie istnieje. Ale w ramach zdrowego rozsądku wolno robić bardzo wiele. Czasami też trzeba komuś wejść na odcisk. Ale to są rzeczy delikatne, o których trudno mówić teoretycznie.

» Dużo pana projektów artystycznych wychodzi poza strefę komfortu niektórych ludzi.

Strefa komfortu jest niebezpieczna. Można zapomnieć o świecie i myśleć, że wszystko jest w po rządku. Gdy tutaj sobie siedzimy, pijemy winko i rozmawiamy, dwadzieścia metrów stąd ktoś led wo żyje, nie mając pieniędzy ani dachu nad głową. Czasami chodzi o to, żeby zwrócić uwagę na pewne rzeczy i wytrącić ludzi z komfortu mającego tendencję do zaślepiania. W tej samej chwili jest wojna w Syrii, ale my tu sobie gawędzimy, mamy dobre ubranka, żyjemy w cieple, i jeste śmy niechętni przyjąć ofiary tej wojny. W Polsce ich nie weźmiemy, chociaż parędziesiąt lat wcześniej to my pukaliśmy do ich drzwi, prosząc o pomoc. Dziś mamy komfort i nie chcemy się z nim dzielić. Oślepia, nie widzimy, co się dzieje. Jedynie nieliczne osoby w Polsce zupełnie prywatnie przyjmują uchodźców, mając prawdopodobnie osobiste doświadczenie z bycia emigrantem, straceniem domu, rodziny, przeżyciem wojny, traumy.

» Myśli pan, że stan dzisiejszy Polski jest konsekwencją niezreflektowanej traumy kraju?

Sam tego jestem dobrym przykładem. Jak zrobiłem pracę Lego, obóz koncentracyjny, która spowodowała, że dużo jeździłem po świecie, spotkałem między różnymi ciekawy mi osobami naukowców ze Stanford University w USA, od których dowiedziałem się, że mam „poholocaustową traumę z drugiej ręki”. Poznaje się to po tym, że mimo tego, że urodziłem się piętnaście lat po wojnie, jako dziecko miałem straszliwe sny o sto sach trupów, biegnących z karabinami Niemcach, wojnie, której sam nie widziałem. Ale okazuje się, że przeżycia przejmuje się od rodziców, rodziny, najbliższych lu dzi, i to jest akurat moja trauma. Ale myślę, że trauma sporej części Polaków pole ga jeszcze na czymś innym, że oni sami lub ich rodziny brali udział w wykańczaniu Żydów, a teraz nie za bardzo chcą o tym pamiętać. Obecność problemu żydowskiego jest dla nich obraźliwa, bo zmusza ich do przypomnienia sobie, że nie jesteśmy niewinni. Przez wiele lat od czasów wojny o tym nie mówiliśmy, temat był zupełnie wytarty z historii, ale z biegiem lat coraz większa skala tego niesamowitego proce deru się ujawnia. Okazuje się, że udział Polaków nie był jakimś marginalnym zjawi skiem, że nawet dziesiątki tysięcy Żydów, przeżywszy holocaust, zginęły z rąk swo ich dawnych sąsiadów. Rozumiem tę traumę. Sam nie chciałbym się ocknąć w sytuacji, wiedząc, że mój dziadek czy ojciec takie rzeczy robili. Ja akurat mam szczęście, że ich między nimi nie było. Wydaje mi się, że nastawienie Polaków w antysemickim czy antyuchodźczym kierunku wynikać może właśnie z tej traumy.

» Co pan sądzi o tym, jak bardzo Polska wraca znów do tematów patriotyzmu i nacjonalizmu?

Nacjonalizm w Polsce był popularny od dawna. Jego teraźniejszy wybuch jest może po równywalny do tego, co miało miejsce tuż przed wojną w 1937 i 1938 roku, a także w latach sześćdziesiątych za generała Mieczysława Moczara, który w 1964 roku został szefem ministerstwa spraw wewnętrznych, kiedy polską partię komunistyczną przeję li narodowcy. Wybuch, który przyszedł teraz, jest fenomenem. Ale może jeszcze za wcześnie, by sytuację tę właściwie skomentować. Niestety pojawia się tu organizacja neofaszystowska, która zaraz po jej powstaniu w Polsce w 1935 roku została zdelega lizowana, ale jak się okazuje, przez cały czas po cichu istniała gdzieś w podziemiu – a teraz znowu odżywa jak jakiś koszmarny wampir, trup, którego nie można dobić. Wiadomo, że to politycy prowokują powstawanie takich rzeczy, robiąc to dla władzy i własnych wpływów, szafując wszelkimi środkami, żeby ściągnąć poparcie. Nazywa się to populizmem. W Polsce najwięcej ulegają mu ludzie ze wsi i małych miasteczek. Niedawno miałem prelekcję po filmie o Josephie Beuysie. Kiedy po skończeniu zada łem publiczności pytanie, czy możliwa jest sztuka prawicowa, jeden z uczestników, psycholog z zawodu, powiedział, że z jego badań wynika, że ludzie o poglądach pra wicowych nie interesują się szerokim światem. Więc w jaki sposób mogłaby zaistnieć

12 13

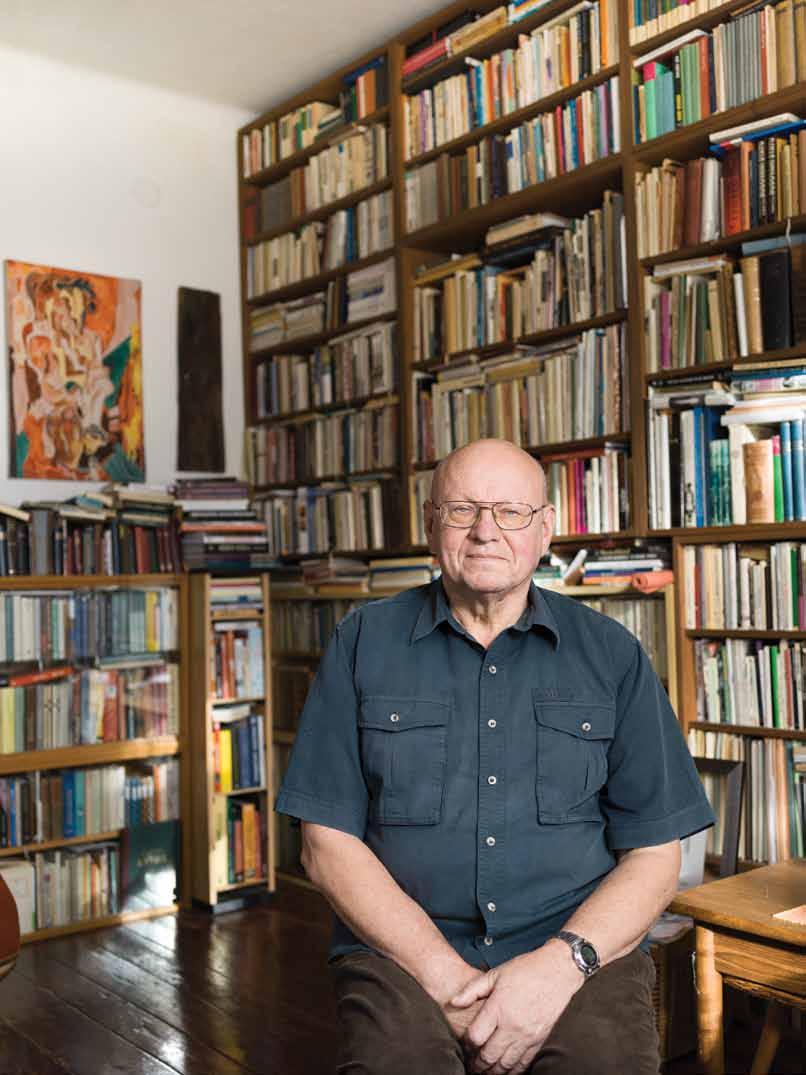

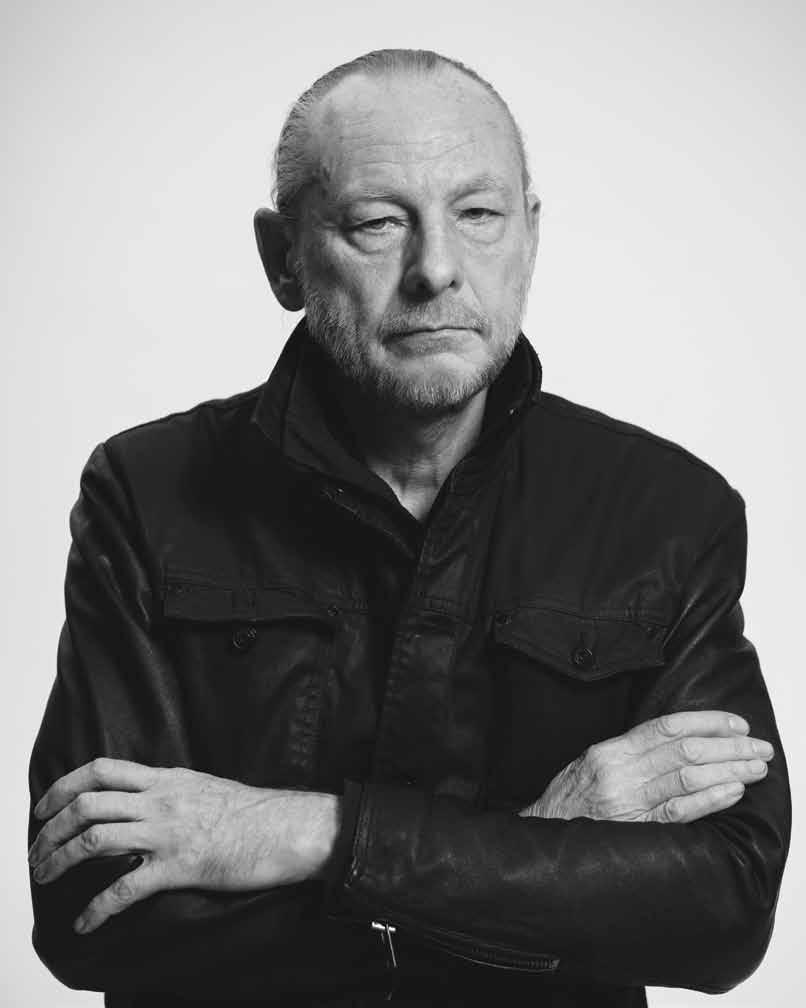

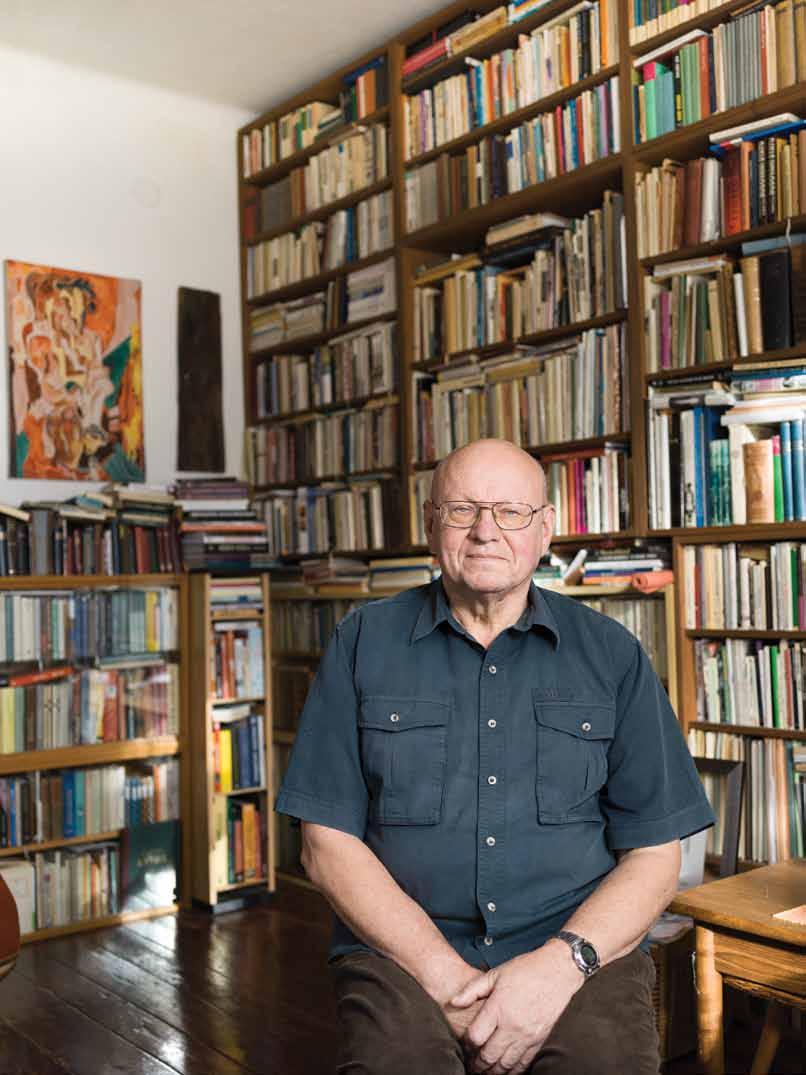

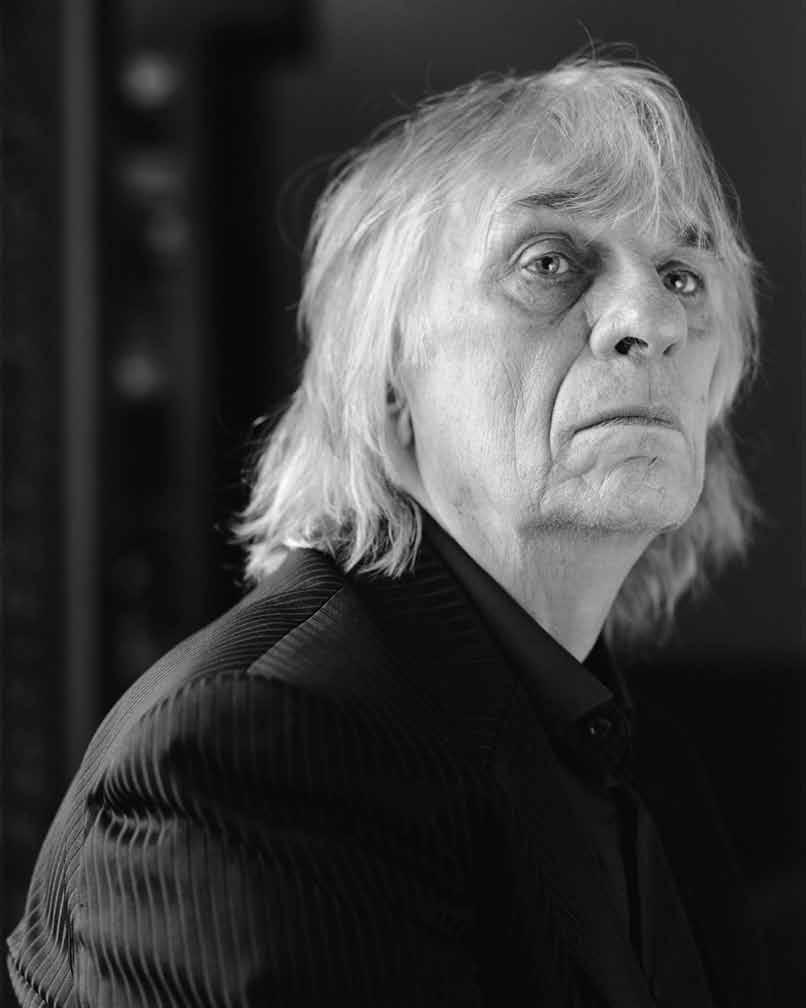

*1959, Pabianice, dziś Warszawa, Polska artysta, performer, fotografik

Saša Uhlová Zbigniew Libera

Zbigniew Libera

sztuka prawicowa, jeżeli człowiek prawicowy jest zamknięty, niechętny do tego, żeby cokolwiek poza „własnym” poznać? Myślę, że populizm nacjonalistyczny trafia właśnie do takich ludzi, którzy nie są otwarci na świat, na nowe horyzonty.

Trzeba wiedzieć, że w Polsce nigdy nie był popularny intelektualizm. Już nawet od przedwojnia raczej bym się nie chwalił, że jestem inteligentem, co znaczy, że się człowieka nie lubi, na wet gdyby był naprawdę „lepszy”.

We wszystkim, co się teraz dzieje, olbrzymią rolę odegrało ostatnich dwadzieścia lat partii neoliberalnej, która nie słucha tych, co nie mają głosu, pieniędzy, zna czenia. „Jeżeli jesteś mocny, to sobie wszystko wywalczysz, a jak jesteś słaby, spadaj.” Każdy odpowiada sam za siebie, niestety olbrzymia liczba ludzi nie jest w stanie dać sobie samemu rady. Jest neoliberalną bajeczką, że Rockefeller został milionerem, kupując jabłka po jednej stronie ulicy i sprzedając je o jeden cent drożej po stronie drugiej. Nie jest to prawda, szczególnie w naszych krajach, gdzie wiadomo, że chcąc uzyskać jakąś pozycję, trzeba pochodzić z już ustawionej rodzi ny. Ostatnio ci, którzy tak bardzo tęsknią do władzy, do której oczywiście potrzeb ne są głosy wyborców – zagospodarowali tych pozbawionych głosu, tych poza burtą, rzucili pieniędzmi i dali złudzenie, że się odegrali na bogatych. Ale trzeba znać warunki, w jakich ludzie głosujący na populistów żyją; największym elektoratem wła dającego Prawa i Sprawiedliwości (PiS) jest południowy wschód Polski przy granicy ze Słowacją w okolicach Rzeszowa. Czasami mam wrażenie, że tam ludzie – ze wzglę du na ich poziom wykształcenia i pogląd na świat – żyją może w osiemnastym wieku. Każdy ogląda w domu telewizję, ale nie patrzy na świat jak na coś realnego, bo jego doświadczenie jest zupełnie inne. Widziałem z tamtych okolic reportaże: pan jest traktorzystą, ma żonę i sześcioro dzieci i po godzinach tankuje – alkohol. I właś nie do takich ludzi trafiają populiści. Populiści chcą ludzi tylko wykorzystać, żeby jedenastego listopada przybyli do Warszawy i coś tu podpalili. W Gdańsku, Trójmieście, Poznaniu nie ma takich marszów. Ale do Warszawy chce przyjechać cała Polska i wywalić tu swoje niezadowolenie.

» Chodzi pan na demonstracje?

Bardzo rzadko. Ostatni raz byłem na demonstracji przeciwko GMO, bo w tych sprawach dość się zaangażowałem. Natomiast „hura” partyjne demonstracje z flagami już mnie in teresują mniej. W Pradze widziałem kilka dobrych demonstracji, w których wszyscy wie dzieli, o co chodzi – anarchiści zatrzymali wtedy neofaszystów niemieckich, czeskich, słowackich i polskich, chcących przechodzić przez Stare Miasto w Noc Kryształową.

» Jaką rolę w tym, co teraz się w Polsce dzieje, odgrywa Kościół?

Polska ma tradycję mocno związaną z katolicyzmem. Jest to trochę sztuczne, bo w przeszłości były tu liczne zgromadzenia protestanckie o różnej orientacji. Niestety jakoś specjalnie się nie przyjęły. Katolicy zdominowali kraj. Natomiast Czechy są antykatolickie – wspomnę mojego ulubionego czeskiego bohatera historycz nego Jana Žižkę, który walczył w bitwie pod Grunwaldem przeciwko Krzyżakom, czyli katolikom, po stronie polskiej. Stracił nawet w tej bitwie oko. Czesi wybrali so bie kościoły protestanckie, w Polsce jest autorytarny, trzymający za mordę i chcący wszystkim rządzić Kościół katolicki. W Polsce uprawia się propagandę, że Czesi są ateistami, ale mieszkałem w Republice Czeskiej przez sześć lat i twierdzę, że tak nie jest. Drzwi do kościołów były ciągle otwarte, w kościołach nie było tłumów, ale wiem, że wszyscy, którzy do nich przyszli, byli prawdziwi, pomagali sobie jak ro dzina, czego w Polsce nie zauważam. Dla mnie zbory protestanckie są bardziej auten tyczne niż te katolickie, które w Polsce odgrywają zgubną rolę. Kilkaset lat temu, kiedy się walczyło o język, a Polska była pod zaborami, rola kościoła była ważna, chociaż nie rozumiem, w jaki sposób, bo przecież msze były po łacinie, co jeszcze pamiętam z mojego dzieciństwa. Ale powiedzmy, że kościół był przechowalnią polsko ści i wokół kościoła katolickiego się Polacy zbierali. Teraz to jednak już w ogóle nie ma sensu. Kościół katolicki zamienił się w swoją odwrotność, chodzi mu o kasę i władzę, w Polsce jest jednym z największych właścicieli ziemi.

» Niektórzy ludzie jednak Boga w swoim życiu potrzebują. Ale kościół ich oszukuje, są tu zboczenia wszelkiego rodzaju, już nie chodzi tylko o pedofilię. W Kościele katolickim księdza powinien obowiązywać celibat, ale wiemy, jak to jest teoretyczne, i idiotyczne z drugiej strony. Były przypadki, gdy ludzie

wiedzieli o księdzu kaleczącym dzieci, ale chodzili i słuchali go, bo, jak mówią, prowadziła ich siła tradycji. Ale ja myślę, że to raczej lenistwo mentalne. Niechęć czy może strach przed podjęciem myślenia na własny rachunek. Jeśli chodzi o mnie, to sam już zapomniałem, kiedy byłem ostatni raz w kościele.

» W latach osiemdziesiątych troszczył się pan o babcię, potem pracował w domu z ludźmi niepełnosprawnymi. Jaką perspektywę w ten sposób pan uzyskał?

Po pierwszej nauczce w więzieniu to był kolejny krok. Po przestępcach miałem psy chicznie chorych. Ale miałem szczęście, bo poziom psychiatrii i szpitali psychia trycznych w Polsce w latach siedemdziesiątych był zadziwiająco wysoki. Moja szefowa zajmowała się „antypsychiatrią” twierdzącą, że choroby psychiczne są wymyślone po to, żeby się pozbyć ze społeczeństwa niechcianych ludzi. A jeżeli mówimy, że ktoś jest chory, musimy potrafić powiedzieć, gdzie w jego ciele znajduje się zmiana, która chorobę powoduje. Tak naprawdę nie ma chorób psychicznych, tylko są ludzie uciekający w choroby po to, żeby się bronić przed społeczeństwem, gdy na przykład nie są w stanie podołać wszystkim żądaniom, które od nich społeczeństwo wymaga. Pracowałem w szpitalu psychiatrycznym, jako psychoterapeuta zajęciowy – poza innymi pracami – i co tydzień prowadziłem zajęcia z pacjentami pod nazwą „psychorysunek”. Pamiętam dzień, kiedy pacjent w odpowiedzi na to, co by chciał posiadać, namalował kolorowy telewizor. I wtedy moja szefowa zdecydowała, że już jest zdrowy. Dla mnie to było przygnębiające, bo zrozumiałem, że zdrowy znaczy głupi albo niewrażliwy. Miarą zdrowia psychicznego był rodzaj niewrażliwości; jak masz miękką skórę, jesteś chory, jak grubą, to zdrowy.

W tych czasach nie wierzyliśmy w skuteczność leków. Przyznam szczerze, że wiele z nich sam przetestowałem i zrozumiałem, jak się chory człowiek czuje. Ale dzisiaj, po latach, już mamy fantastyczne leki. Już się nie idzie w kierunku leczenia socjalnego, człowiek zaraz nabiera grubej skóry. To, czym się pacjent przejmuje, od razu się odcina chemicznie.

» Czy w społeczeństwie nastaje nowa normalizacja?

Na pewno tak, już kiedyś tu istniała. Mówiąc o najbardziej trywialnych rzeczach, na przykład w latach dziewięćdziesiątych trzeba było wszystkim wyraźnie powiedzieć, że kobiety powinny golić sobie łydki, i nie jest dobrze mieć pod pachami włosy, żeby doszlusować do reszty świata, który już to stosuje. Poprzez swoją pracę poru szałem wtedy te tematy, opowiadając rzeczy niepopularne, mówiąc o tym, że nasze ego nie jest naszym własnym wytworem, tylko społeczeństwa, i jak urządzenia społeczne wyciskają z nas to, kim potem jesteśmy. Dzieci bawią się „winnymi” zabawkami i po przez cały szereg propozycji kreuje się i wytwarza ludzi. To, co zaaplikowano w la tach dziewięćdziesiątych, specjalnie się nie zmieniło. Ale ważniejszy niż normali zacja jest dziś temat propagandy.

» Czy jest w Polsce dużo aktywistów?

Są tu i jest ich coraz więcej. Widoczne są ekstrema, neofaszyści, ale mamy tutaj również całą masę organizacji cichych, robiących poważne rzeczy; w Warszawie jest to na przykład Bęc Zmiana czy Against Gravity, organizująca edukację w mądry sposób. W Poznaniu słynny już squat Rozbrat. Są też inne – widzę je nawet w mniejszych mia stach na terenie całej Polski. Mamy tutaj ludzi, którzy lubią działać społecznie, którzy rozumieją, że Internet pomaga, ale nie wystarczy. Żadne media społecznościo we nie załatwią nam sprawy, a wręcz je pogarszają. Trzeba się widzieć, spotykać, bo rozmawiać ze sobą naprawdę jest czymś zupełnie innym niż kontakty na Facebooku.

» Jakie tematy te organizacje podejmują?

Wszystkie, bo są przeróżne. W Polsce jest teraz na przykład bardzo duży ruch kobie cy, prawdopodobnie sprowokowany ich patriarchalnym neofaszystowskim traktowaniem. W Polsce nie ma aborcji – Polki jeżdżą do Czech, na Słowację albo do Niemiec, żeby ją zrobić. Tuż przy granicy są kliniki czeskie, dobrze to pokazuje film Kler. Ja w siłę kobiet wierzę. Jak widziałem czarny marsz dwa lata temu, byłem pod wielkim wrażeniem. Była fatalna pogoda, zimno, lał deszcz, tłum pięćdziesięciu tysięcy ko biet i mężczyzn, ale głównie kobiet, które miały parasolki… Ja po prostu wierzę, że kobiety dziś mogą mieć siłę, której mężczyźni już nie mają. A nie mogę zrozumieć demokracji, dopóki istnieje zakaz aborcji – to przecież nie jest demokracja. Żaden

14 15

Zbigniew Libera

Zbigniew Libera

człowiek nie jest własnością państwa czy rządu. Każdy sam jest właścicielem swoje go ciała i może z nim robić, co chce. Z tego najbardziej drastycznego i widocznego powodu nie jest Polska krajem demokratycznym, i też dlatego, że nie daje możliwości głosu dla każdego. W naszym kraju mają głos tylko celebryci, sportowcy, modelko -aktorki, którzy jednak nie mają niczego do powiedzenia. Ale u was jest tak samo. Normalny człowiek może sobie krzyknąć coś na ulicy, ewentualnie przyjdzie policja i wlepi mu za to mandat. W ogóle nie wolno mówić.

» Czy to nie kwestia mediów wolących celebrytów?

Nie. To, kto ma głos, jest problemem społecznym. Jest zasadnicze, kto będzie wysłu chany i czyj głos będzie na serio przyjmowany. W tej chwili nie mówię o ludziach robiących anonimowe hejty, którzy, gdyby nie Internet, zamilkliby ze strachu, ale o zwykłych ludziach. Pytanie brzmi, kto może być autorytetem, kto i jak może coś powiedzieć, i na jakiej platformie zostanie temat przedstawiony. Dla tego za ważną uważam dziś działalność grup, nazwijmy je anarchizującymi, które w Polsce organizu ją własne festiwale, mitingi, spotkania, gdzie człowiek może czuć się wolnym i po trzebnym. Mam nadzieję, że to się będzie rozpowszechniać. My dwoje mamy gwarantowane prawo do słyszalnego głosu – ty jesteś dziennikarką, ja artystą –i korzystamy z tego na tyle, na ile możemy. Mówimy rzeczy, które w inny sposób nie mogłyby być wypowiedziane. A właśnie umożliwianie głosu wszystkim, którzy go mieć nie mogą, wydaje mi się w naszych czasach być naprawdę istotną funkcją sztuki.

» Czy istnieje zagrożenie, iż polscy artyści będą ponownie musieć działać w kręgach podziemnych?

Sytuacja w Polsce w tej chwili wydaje się być rodzajem podziemia; obecna władza za brała wszystkie pieniądze z kultury, bo trzeba było dać masowo 5 złotych każdemu dziecku z rodziny, gdzie było ich powyżej dwójki. Ale kultura była niedofinansowy wana już wcześniej. W tej chwili, kiedy nikt niczego od artystów nie kupuje, my je steśmy pozostawieni sami sobie. Mamy zdechnąć albo wyjechać. Ale są tutaj też artyści, jak na przykład Wilhelm Sasnal, Mirosław Bałka czy Piotr Uklański, którzy sobie świetnie radzą. Są to Polacy, ale działający na Zachodzie, to znaczy w innych relacjach finansowych. Natomiast artyści żyjący w Polsce poczuli potężne załamanie trzy lata temu z przyjściem nowej władzy. Sytuacja wygląda fatalnie. Ja sam teraz muszę dużo pracować i robić różne rzeczy po to, żeby w ogóle przeżyć. Robić coś swojego zdarza mi się coraz mniej, bo po prostu nie mam za co. A podobnie wygląda sytuacja u innych artystów, może nawet gorzej. Neofaszystowska nacjonalistyczna władza od samego początku deklarowała, że pierwszą rzeczą, która jest od razu do odstrzału, jest sztuka współczesna, dlatego że próbuje mówić, zabierać głos na tematy społeczne, dawać głos innym. Ale i tak powinniśmy być w miarę zadowoleni w porównaniu z tym, co dzieje się na Węgrzech. Byłem mimowolnym świadkiem rozmontowywania sztuki madziarskiej. Kilka lat temu byłem umówiony z węgierską kuratorką na przeniesienie mo jej wystawy retrospektywnej do Budapesztu, ale w atomowym tempie zmienił się dyrektor insty tucji, w wyniku czego zostałem wyrzucony z projektu, a kuratorka musiała wyjechać z Węgier. Jeszcze dwadzieścia lat temu było na Węgrzech wielu ciekawych artystów, a teraz nie ma nikogo. Polska władza chciałyby Węgry naśladować, ale na szczęście mamy 38 milionów obywateli i więcej dużych miast, a tym samym większy opór społeczny. Polacy nie tak łatwo dają się spacyfikować.

» Czy Polsce pomaga bycie członkiem Unii Europejskiej?

Dla mnie Unia Europejska odgrywa zasadniczą rolę. Przed ostatnimi wyborami najważ niejsi polscy politycy po cichu mówili, że wyjdziemy z Unii. I postawiłem sobie ce zurę: „W momencie wychodzenia Polski z Unii w dwie godziny się spakuję i wyjeżdżam stąd – chociażby do Berlina czy Pragi”. W historii Polski musieli inteligenci cią gle wyjeżdżać, opuszczać kraj z różnych powodów. Chociaż w Czechach procent wyjeż dżających w stosunku do wielkości kraju był znacznie większy niż u nas. Widziałem załamanie czeskiej kultury poprzez liczbę ludzi wyrzuconych…

» Jaki ma pan stosunek do Republiki Czeskiej?

Trzeba sobie uświadomić, że Republika Czeska jest rodzajem niespełnionego marzenia Polaków. Przynajmniej sporej ich części. Polacy chcieliby, żeby w Polsce była taka wolność, jak w Czechach za czasów Václava Havla, ale nigdy nie byli w stanie tego zrobić. Ja się w Czechach bardzo dobrze czułem, znalazłem tam wszystko, czego nie mogłem znaleźć w Polsce. Czułem się tam zawsze jak w domu, jakbym tylko wyszedł do

innego pokoju, w którym wolno palić. Mieliście mądrą decyzję o zalegalizowaniu pew nych narkotyków, bo tylko legalizacja może spowodować ich kontrolę. Pamiętam właś nie świętej pamięci Václava Havla, który powiedział, że musi uniewinnić siedemna stoletniego skazanego za jointa, bo nie mógłby spojrzeć na siebie w lustro, bo sam przecież też palił. Takiego prezydenta, jakim był Václav Havel, wszyscy by chcieli mieć, mimo że też coś tam od czasu do czasu przeskrobał.

» Kto może Polsce przynieść zmiany pozytywne?

Musi to być ktoś z nowej generacji. Ludzie starsi są już wypaleni i nie rozumieją współczesnego świata. Pewien problem stanowi to, że mamy tutaj tylko dwie partie: Platformę Obywatelską (PO) i Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS), a olbrzymia liczba ludzi wcale nie chce żadnej z nich, niestety nie ma żadnej innej propozycji. Zaryzykuję i wymienię nazwisko człowieka, wobec którego żywię teraz nadzieję. Jest nim Robert Biedroń, do niedawna prezydent miasta Słupsk, oficjalny gej, którego mieszkańcy miasteczka szanują. Życzę mu, żeby się udało, bo na pewno polityczna konkurencja będzie go chciała zmiażdżyć. Jeśli pan Robert nie zmieni się za bardzo (politykom nie można ufać i cały czas trzeba im patrzeć na ręce), byłbym w stanie go poprzeć. Jak na polityka jest młody – ma czterdzieści kilka lat.

» Czy istnieje w Polsce dialog pomiędzy generacją Roberta Biedronia i tymi, którzy wywalczyli demokrację?

Nie dostrzegam żadnego dialogu, są to inni ludzie. Poznałem kiedyś Lecha Wałęsę –to człowiek kompletnie odklejony od rzeczywistości. Ludzie z generacji Solidarności byli albo wygranymi, korzystającymi z sytuacji i żyjącymi na dobrym poziomie, albo w rezultacie zmiany stracili, i wielu z nich poszło do kościoła, do Radia Maryja. Jeszcze o tej najstraszliwszej broni katolików w Polsce nie mówiliśmy. Ojciec Rydzyk zgarnął wszystkich niezadowolonych i przegranych z owej generacji. A znam takich.

» Które wydarzenia były dla pana przełomowe w demokratycznych latach Polski?

Po 1989 roku wszystko szło w miarę dobrze do czasu, kiedy pojawili się bracia Kaczyńscy. Musimy wspomnieć o katastrofie smoleńskiej. Jest to trudny temat, ale trzeba zapytać, dlaczego dziewięćdziesiąt osób z rządu poleciało jednym samolotem, nawet nie na prawdziwe lotnisko. Szczerze powiem, za bardzo nie żałowałem, bo aku rat w samolocie byli przedstawiciele dość nieprzyjemnej prawicy, ale świeczkę nad nimi zapalić trzeba.

Z katastrofy smoleńskiej niestety zrobiono propagandę. Niesamowitą manipulacją Kaczyńskiego i jego ekipy PiS Kaczyński nabrał i oszukał miliony ludzi wmawiając im, że był to zamach. Katastrofa dużo zmieniła; cała prawica zaczęła na niej bazować i wokół niej się organizować. I ten negatywny ruch doprowadził nas do teraźniejszej sytuacji. Natomiast pozytywnym ruchem, który zauważyłem na początku dwudziestego pierwszego wieku, była popularność sztuki, być może jako wynik dużych zarobków kilku arty stów, pisania o nich w gazetach, snobizmu. Pamiętam, gdy poszedłem na wernisaż, na którym były tłumy, chyba dwa tysięcy ludzi, a ja nie znałem tam ani jednej osoby. Pomyślałem sobie, że coś się w Polsce zmienia, ale trwało to tylko dziesięć lat.

» Czy sztuka jest dziś w Polsce narzędziem propagandy?

U nas tego nie ma, bo prawica nie potrafi znaleźć sobie swoich artystów. Jest to warte doku mentacji – budują pomniki, tablice, ale na bardzo słabym poziomie. Po tym, co teraz się dzie je, zostanie ciekawy okres historii polskiej sztuki, zapaści estetycznej. Sztuka robiona ofi cjalnie jest bardzo amatorska.

» Mówiąc wcześniej o anarchii, miał pan na myśli, iż społeczeństwo ma większe szanse na przetrwanie w sensie niehierarchicznym?

Dzisiejsze systemy władzy są niewydolne. Jeśli nie weźmiemy spraw we własne ręce, a nie będziemy mieć prawa do kontroli polityków, to się skończy źle i szybciej niż nam się wydaje, przede wszystkim katastrofą ekologiczną. Politycy nie robią nic w kierunku redukowania gazów cieplarnianych. Były już (na szczęście) polski mi nister ochrony środowiska zaczął wycinkę Puszczy Białowieskiej, jedynej natural nej puszczy, jaka jeszcze istnieje w Europie. Patrzył na pierwotną puszczę, a nie

16 17

Zbigniew Libera

Zbigniew Libera

widział lasu, tylko coś w rodzaju uprawy drewna, a drewno to deski, zaś deski to pieniądze. Musimy się zastanowić, czy wolimy zysk, czy życie. Mimo wszystko, pozostaję optymistą, i wierzę, że to, co się teraz dzieje, jest tylko spraw dzianem, że jednak przezwyciężymy konserwatywne poglądy, rozum wróci, a my zorganizujemy nasze społeczeństwo w niehierarchiczny sposób – dopuścimy ludzi do głosu i nie będziemy centralizo wać władzy jak w tej chwili. Ludzie powinni kierować się swoim lokalnym środowiskiem, mniej szym nawet niż obszar województwa. Dlaczego mam głosować na nieznanych i niewiarygodnych cwa niaków? Tylko dlatego, że wstawiono ich na partyjne listy? I jeszcze mi się przy tym wmawia, że mam rzekomo jakieś prawo głosu? Małe grupy są bardziej skuteczne, poza tym każdy może brać udział w życiu społecznym. Więc dzisiaj więcej słuchajmy, mniej rządźmy.

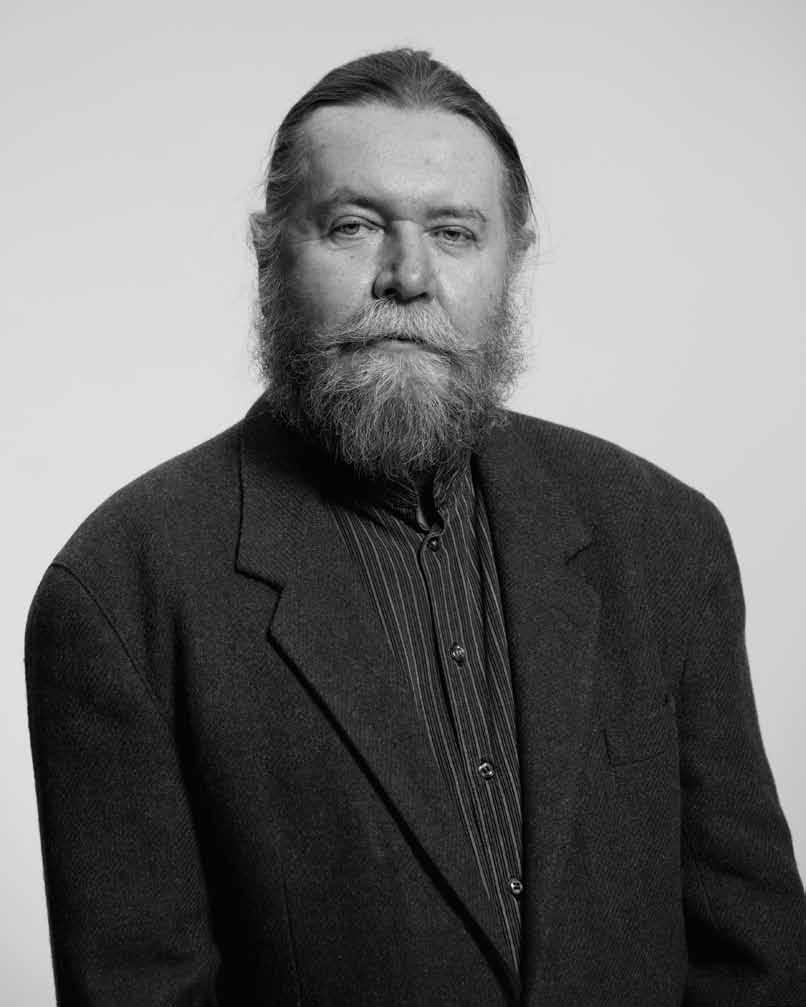

Zuzana Mistríková

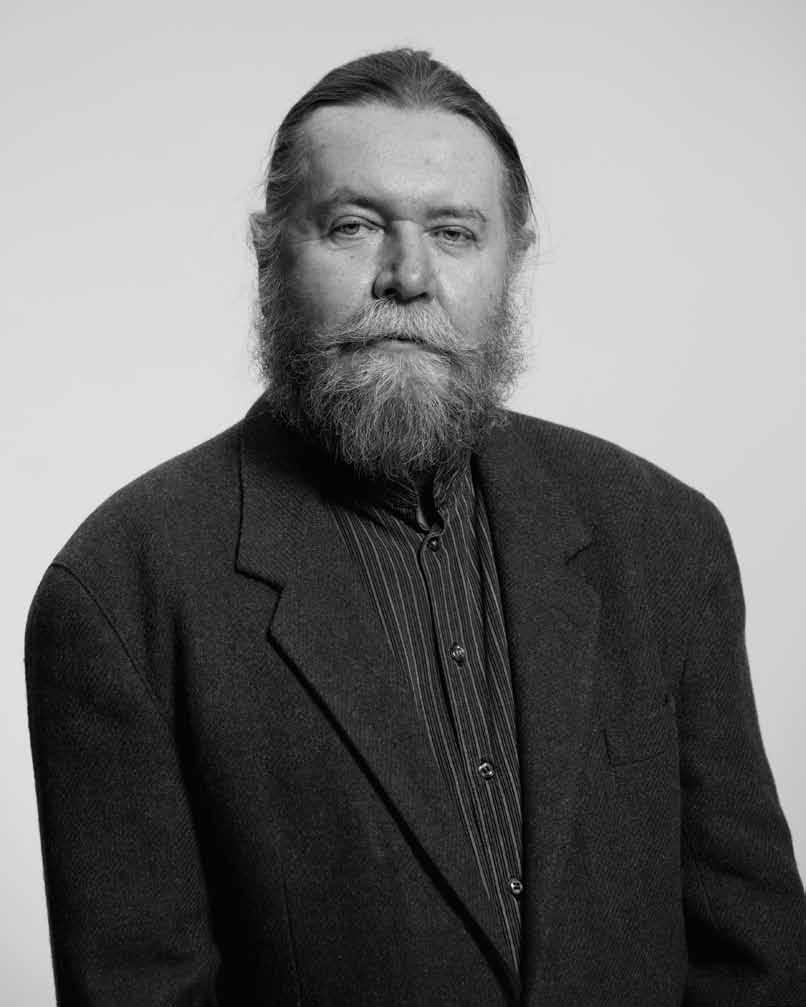

*1967, Bratislava, Československo, dnes Slovensko študentská revolučná aktivistka, filmová producentka

» Zuzana, ako sa študent v dvadsiatich dvoch rokoch dostane do súkolia dejín ako vy v roku 1989?

Je asi prirodzené, že študenti sa vždy na svet dívajú kritickými očami a chcú ho urobiť lepším. Keď sa blíži tridsiate výročie novembra, uvedomujem si, že sme štu dovali v čase, kedy od roku 1968 prešlo len dvadsať rokov, a pritom sme mali pocit, že ide o hlbokú históriu. Vnímali sme „plíživú“ normalizáciu, ktorá po roku 197 nastala, a frustráciu rodičov, ktorí predtým zažili šesťdesiate roky - otvorenosť, slobodného ducha. Ja som mala to šťastie, že som vyrastala v rodine, kde sa o ve ciach hovorilo priamo. Nevplížila sa do nej schizofrénia a dvojitá pravda, typická pre znormalizovanú krajinu.

V roku 1989 som študovala divadelnú dramaturgiu. Umelecké školy – akokoľvek boli normalizo vané – boli vždy priestorom pre slobodu vyjadrenia, miestom reálnych debát – napriek tomu, že v tom čase diskutovať naozaj nebolo obvyklé. Na umeleckých školách to ale ani inak nejde, človek je zvyknutý na dialóg, premýšľanie, vyjadrovanie sa. V Československu boli tri drama tické vysoké školy – v Brne, Prahe a Bratislave, a naše ročníky úzko spolupracovali. Keď sa v piatok 17. novembra 1989 demonštrovalo v Prahe, v sobotu ráno sme mali informácie o tom, čo sa na Národnej triede stalo a ako reaguje študentská a umelecká komunita, naozaj z prvej ruky – od brnenských kolegov, ktorí nám volali, a od Petra Gábora študujúceho na DAMU. Ten hneď ráno sadol na vlak do Bratislavy. Ani chvíľu sme nerozmýšľali, či zaujať postoj, jednoducho bolo potrebné okamžite niečo robiť. Uvedomovali sme si, že ak by režim zareagoval tak, ako ešte v januári na Palachove dni alebo rok predtým na Sviečkovej demonštrácii, pravdepodobne by sme všetci pochovali svoje štúdiá a kariéry. Ale ak viete, čo sa stalo vašim kamarátom, a vidíte svojich pedagógov, ako sa v nedeľu večer postavia na javisko a povedia, že na protest proti brutálnemu zásahu proti študentom nebudú hrať, nemáte o čom rozmýšľať a idete do toho. A po chvíli si uve domíte, že ste sa ocitli v centre diania. VŠMU sa v Bratislave stala miestom, odkiaľ sa v prvých dňoch a týždňoch koordinovali všetky aktivity. Malo to za následok, že postoje študentov sa pre ľudí stali zásadné a ešte dlho – minimálne do volieb v júni 199 – ich vnímali ako ručičku kom pasu, ktorá ukazuje na to „správne a morálne“. Bol to neuveriteľný záväzok a zodpovednosť.

» Je ale rozdiel byť v dave alebo sa davu prihovárať.

Každý má vlohy na niečo iné, ja som mala vlohy organizačné. Na bratislavskej diva delnej fakulte sme sa zhodou okolností rozhodli ako generácia začínajúcich tretia kov využiť vtedy päťdesiate výročie 17. novembra 1939, študentského dňa, k obnove niu slávnostného burleskného spôsobu krstu prvákov. Dokonca sme mali povolenie na alegorický sprievod mestom, ktoré nám ale, samozrejme, pár dní pred jeho konaním zrušili. Niekde dali študentom aj rektorské voľno, aby poodchádzali na víkend do mov. Začali tušiť, že november je výbušný. A práve okolo prípravy študentského po dujatia na VŠMU sa vyprofilovala skupinka ľudí – niekto ho režíroval, iný vybavoval kostýmy, a to sa nám prelialo do pondelka 2 . novembra. Keď naši kolegovia v Prahe zažívali hrôzy zásahu na Národnej triede, my sme oslavovali. Ale keď sme v pondelok

ráno viezli späť do Slovenskej televízie kostýmy, do školy sme sa vracali rovno s podpisovými hárkami a vyhlásili štrajk.

Ľudia majú v pamäti z novembra niekoľko tvárí, ale aktívnych ľudí bolo omnoho viac, robili rovnako dôležitú prácu, len ju možno nebolo navonok vidno. Argumentovať do prvej debaty do televízie alebo sa postaviť na pódium išiel ten, kto bol „po ruke“, a potom mu to už zostalo. Prvú diskusiu nám ponúkla rakúska televízia. Československé médiá ešte hlásali oficiálnu verziu udalostí, a to, že v Prahe musela zasiahnuť polícia proti študentom, ktorí vyvolávali nepokoje, a cez rakúske veľvyslanectvo prišla ponuka priestoru v diskusnej relácii Club 2. Bolo to nesmierne dôležité, pretože južné Slovensko, a špeciálne Bratislava, rakúsku televíziu sledovali. Samozrejmou voľbou bol prekladateľ Peter Zajac, ktorý bol súčasťou vznikajúceho slovenského hnutia Verejnosť proti násiliu, a ja – keďže som vedela po nemecky – som mala na diskusiu do ORF ísť za študentov. Dokonca sme počas pár hodín dostali víza, asi jedny z pos ledných, pretože vízová povinnosť bola potom zrušená. Keďže v ten deň sa i Slovenská televízia rozhodla pripustiť živú diskusiu, do Viedne sme nakoniec nešli. Debata bola bizarná: na jednej strane sedeli reprezentanti socialistického establišmentu, šéfovia veľkých podnikov, žiadni kádrovníci alebo politruci. Ich mená si už nepamätám, nezaujímali ma, človek vtedy netušil, kto je kto, lebo to bolo jedno. A na druhej strane sme sedeli piati – slovenskí tribúni Milan Kňažko a Jano Budaj, Vlado Ondruš, Miroslav Kusý a ja. Úporne som sa snažila v debate neza spať, keďže dni boli hektické, prakticky bez spánku. Tí oficiálni sa mi otázkami snažili pod sunúť, že my, študenti, sme zneužití na politickú agendu a že od prvých dní neustále meníme, čo vlastne chceme. Ustála som to, pretože ako študenti sme mali jasno – základnou požiadavkou bolo vyšetriť zásah proti študentom 17. novembra a potom sme chceli, aby sa veci v spoločno sti vrátili do normálu, napríklad aby sme mali zaručenú akademickú slobodu. V tom čase boli napríklad na vysokých školách výbory komunistickej strany, ktoré ťahali študentov od prvého ročníka cez SZM ku kandidatúre na členstvo v strane.

» Ako vyzerala novembrová revolúcia priamo v uliciach Bratislavy?

V stredu 23. novembra bola prvá veľká demonštrácia v Bratislave na Námestí SNP. Keď sme na ňu odchádzali zo stretnutia študentov a pedagógov zo školského diva delného štúdia Reduta, na veľkých mramorových schodoch stál Štefan Kvietik a so slzami v očiach hovoril, že keď sa stane to isté, čo v piatok v Prahe, máme utekať do bočných uličiek a dávať na seba pozor. Vtedy sme nevedeli, či bude demonštrácia trvať dve či päť minút, a ako dopadne. Napokon nik nezasiahol a zo stretnutí na námestí SNP sa stal každodenný rituál. Postupne posilňoval v ľuďoch pocit vzájomno sti. Situáciu vtedy veľmi rýchlo chytili do rúk slovenskí výtvarníci – mesto bolo oblepené Danglárovými transparentmi a plagátmi a skvele tiež zapracovala ľudová tvorivosť. Aj dnes, keď sa v našej alebo vašej krajine stane politický prešľap, prakticky na druhý deň môžete vydať knihu karikatúr. Keďže som bola v novembri 1989 v organizačnom zákulisí, vnímala som dianie asi trochu inak ako ľudia v dave. Keď si ľudia pripínali stužky a štrngalo sa kľúčmi „už vám odzvonilo“, fascino valo ma to. Z ľudí z toho obdobia mám veľmi silný zážitok – po prvých dňoch sa prestali cítiť ohrození. Aj keď stále nebolo jasné, či nastala politická zmena, videla som, ako úžasne oslo bodzujúce to pre nich bolo. Stretnutia boli neuveriteľným koncentrátom pozitívnej energie. Na jednu demonštráciu som išla neskôr, a keď som sa snažila predrať cez námestie naplnené päťde siatimi tisícmi ľudí, hneď ako ma prví zbadali, roztvárala sa predo mnou ulička. Doteraz mám z toho zimomriavky.

Vždy, keď sa v našej krajine deje niečo divné, v deväťdesiatych rokoch aj teraz, spomeniem si, že sú to stále tí istí ľudia, ktorí vtedy stáli na námestiach a žia dali zmenu. Stal sa z toho návyk – zdieľať veci na námestiach, aj potreba vidieť, že nie som sám, kto si myslí, že veci majú byť inak. Niektoré veci sa musia naozaj zažiť na vlastnej koži.

» V roku 2 18 sú slovenskí študenti znovu v uliciach.

Áno, vlnu verejných protestov na Slovensku znovu spustili študenti a mladí ľudia. Pripomína mi to novembrový moment v tom, že nebyť mladých ľudí, slovenská verej nosť by sa nikdy nedozvedela o tom, čo sa deje napríklad farmárom na východnom Slovensku. Samozrejme o tom niektorí novinári písali, ale v médiách, ktoré nemajú široký dosah. Až po strašnej vražde novinára Jána Kuciaka a architektky Martiny Kušnírovej zažili aj tieto médiá „boom“ a ľudia sa znovu začali zaujímať o to, čo sa u nás vlastne deje. Keď žijete v krajine, kde sa v novinách každý deň objaví dvadsaťpäť nových korupčných káuz a podvodov, rezignujete, pretože si vôbec neviete predstaviť, čo s tým ako jeden človek môžete spraviť. Podvody sa samozrejme dejú vo

18 19

Zbigniew Libera Zuzana Mistríková

Zuzana Mistríková

»

veľkom vo veľkej politike, ale keď niekto mafiánskym spôsobom ovláda cez politiku mestečko, nemáte šancu. Je to ako za nevoľníctva. Dnes a na Slovensku. Strašné.

V čom je najväčšie nebezpečenstvo pre demokraciu?

Premiérovali sme film Toman, kde sa okrem zákulisia veľkej politiky dozviete to, že rok 1948 bol možný predovšetkým preto, že to pripustili štandardné demokratické strany – neodčítali, v čom je nebezpečenstvo. Ako vraví režisér Ondřej Trojan, keď sa k látke v roku 2 11 dostal, netušil, o čo bude aktuálnejšia pri premiére. V slovenskom parlamente sa hlasuje kvôli zmene ústavy a voľbe ústavných sudcov, v Čechách vznikajú koalície s podporou komunistov. Sú to strašne nebezpečné veci. V jednej chvíli to vyzerá ako politický kalkul, pretože riadenie krajiny musíte zdieľať s viacerými stranami. Ale ak prekročíte určitú hranicu v zmysle demokra tického zmýšľania, môže to mať strašné následky. A vy si toho pri prvom opatrnom prekročení hranice vôbec nie ste vedomí. Vravíte si, je to ústupok, ktorý je v po riadku, lebo vďaka nemu presadíte niečo dôležité a správne. Lenže potom zistíte, že ste sa pustili cestou do pekla a nie je jednoduché vrátiť sa z nej späť… A tu sa podľa mňa teraz na Slovensku aj v Čechách nachádzame. Na Tomana sa pozerá so zi momriavkami nielen preto, že sú to reálne udalosti, ktoré dostali Československo na štyridsať rokov do iného kontextu, ale aj preto, že si uvedomíte, že sa to deje aj dnes. Niekedy, keď sledujem politické debaty, mám chuť spýtať sa politikov, či sa nehanbia takým spôsobom komunikovať o veciach, ktoré sú pre našu krajinu dôležité. Shooty nedávno nakreslil krásnu karikatúru v súvislosti s naším predsedom parlamen tu a jeho odpísanou rigoróznou prácou: dve detičky sú v škole, jedno nakúka a druhé hovorí: „Nebuď ako Andrej Danko!“ Čo je to pre našu krajinu za signál, keď sa ľudia správajú spôsobom, že keby mali päť rokov, vyrieši to pár na zadok?

» Práve o mravoch a tiež komunizme je i predchádzajúci film, ktorý ste produkovali, Učiteľka. Podľa čoho si ako producentka vyberáte témy?