6.5 mm spine INTELLIGENT LIFE THE AWARD-WINNING bi-monthly ALSO ON iPAD, iPHONE & ANDROID

HOW TO

ERADICATE NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2014

A DISEASE SIX

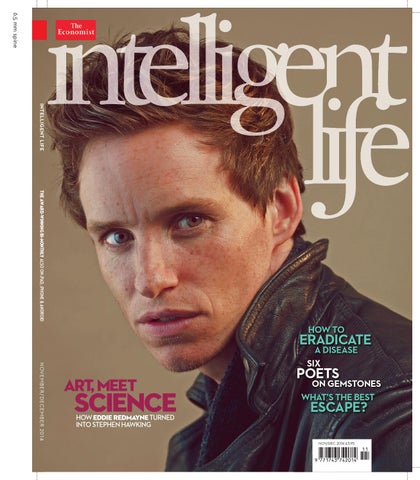

ART, MEET

SCIENCE HOW EDDIE REDMAYNE TURNED INTO STEPHEN HAWKING

POETS

ON GEMSTONES WHAT’S THE BEST

ESCAPE? NOV/DEC 2014 £5.95

CONTENTS

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2014 FROM THE EDITOR 12 MASTHEAD 14 CONTRIBUTORS 16 LETTERS 18

22 THIS SEASON The most interesting things to see and hear over the next two months, from Rodin’s creative process in Paris to a great Turkish movie

30 INTELLIGENCE

RESEARCH How digital techniques are transforming the humanities THE WINE-LIST INSPECTOR Boozing in Beijing FOOD My Madeleine: a bowl of soup in Ghana, by Taiye Selasi

The Kitchen Dialogues: Puy lentils and fillet of beef Lipsmacking: a toasted truffle sandwich in Paris THE BIG QUESTION What’s the best escape? A GAME, A GADGET AND AN APP “Destiny”, and a revolutionary speaker THE MUSIC OF SCIENCE Oliver Morton on engineering the weather READING THE GAME Which is better – baseball or cricket?

30 34 35 36 36 38 41 42 44

44

126 48 STYLE

JEWELLERY Six gorgeous pieces, six original poems APPLIED FASHION In the realm of the senses THE LINE OF BEAUTY The hood, from fairytales to Valentino NEW BUILT TO LAST A design that has stood the test of time NEW A MATTER OF TASTE Kassia St Clair steers a course through the shops

106 CULTURE

AUTHORS ON MUSEUMS Claire Messud on fine art in Boston AT THE CINEMA Can a film be too beautiful? By Tom Shone BOOKS Notes on a Voice: J.G. Ballard, by Tom Graham

Found in Translation: Geert Mak Six Good Books: Ian McEwan, Hilary Mantel and more VISUAL CV Timothy Spall, this year’s Best Actor at Cannes

116 PLACES

58

48 56 58 62 64

106 111 112 112 113 114

MAIN FEATURE The Turks and Caicos: Charles Laurence’s second home GOING NATIVE When in...New Zealand CARTOPHILIA Star trek: the map that makes sense of the universe SEVEN WONDERS Christopher Le Brun, president of the Royal Academy WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE A monkey with a difference in Ethiopia

116 122 124 126 128

BACK PAGE LANDSCAPES OF THE MIND Robert Macfarlane on Jules Verne

130

Swotting all over the world The team from St John’s College, Johannesburg, that represented South Africa in the Kids’ Lit Quiz 2014 in Falmouth, Cornwall Feature, page 66

features 66 the storySellers

A new museum, a global literary quiz and a charity that gets teenagers writing poems: Tim de Lisle tracks three bright ideas to boost literacy

76 HOW TO ERADICATE A DISEASE

Donald Hopkins has already seen off one disease. Now he has another in his sights, and it’s a particularly nasty one. Tom Whipple reports

84 photo essay: SLICES OF LIFE

There’s something special about your first vinyl record. Dean Belcher captures it

96 THE MAKING OF A ROLE

For Eddie Redmayne, playing Stephen Hawking meant two years of graft and spreadsheets. Clemency Burton-Hill follows him through the process

cover photograph ian winstanley

maja daniels

© 2014 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of The Economist Newspaper Limited. Published by The Economist Newspaper Limited, 25 St James’s Street, London, SW1A 1HG, telephone +44 (0)20 7830 7000; e-mail intelligentlife@economist.com; www.moreintelligentlife. com. ISSN 1743-7424. Where opinion is expressed it is that of the author and does not necessarily coincide with the editorial views of the publisher or The Economist. All information in this magazine is verified to the best of the author’s and the publisher’s ability. However, The Economist Newspaper Limited does not accept responsibility for any loss arising from reliance on it. Printed by Wyndeham Group.

PEFC certified This copy of Intelligent Life is printed on paper sourced from sustainably managed forests certified by PEFC www.pefc.org PEFC/16-33-582

9

In theory, it is impossible to combine a perpetual calendar with a moon-phase display also indicating the constellation of the moon, earth and sun without impairing legibility of the watch.

RICHARD LANGE PERPETUAL CALENDAR “Terraluna”

The Richard Lange Perpetual Calendar “Terraluna” combines me-

opposite side showcases a horological innovation: Lange’s patent-

chanical complexity with remarkable functionality. Apart from

ed orbital moon-phase display. It reproduces the moon phases with

hours, minutes, and seconds, the dial features four precisely jumping

extreme precision and shows the ever-changing constellation of the

calendar indications that are always unambiguously legible. The

moon relative to the earth and the sun. The display tracks the synodic

But only in theory.

The patented orbital moon-phase display

month of the moon so faithfully that if the watch runs without inter-

of the movement. The calibre L096.1 is endowed with a patented

ruption, it has to be corrected by one day only after 1058 years. In the

constant-force escapement. It controls the enormous power stored in

centre of the display, the earth rotates about its own axis once a day.

the twin mainspring barrel and assures consistently high precision

The fixed position of the sun is occupied by the balance on the edge

during the power-reserve period of 14 days. www.alange-soehne.com

You are cordially invited to discover the A. Lange & Söhne collection at our Boutiques: Abu Dhabi · Dresden · Dubai · Hong Kong · Lisboa · Munich · Palm Beach · Paris · Shanghai · Singapore · Tokyo

FROM THE EDITOR

Lights, camera, research When you edit a cultural magazine, you have to decide where you stand on actors. There are a lot of them, they are highly recognisable, and many are on offer as interviewees. But the offer often has a Faustian tinge: if you accept, you lose a piece of your magazine’s soul. Not to the actor or actress concerned, who is probably deeply soulful, but to the grim machinery behind them. The interview may be for only an hour, it may be in a hotel, the publicist may be in the room: everything conspiring to deliver a piece of pap. And star power – or pr power – is now such that photo approval, even copy approval, is not uncommon. Our parentage, at the independent-minded Economist Group, means that we couldn’t play that game even if we wanted to. The day after our last issue closed, an e-mail came in from Clemency Burton-Hill, who wrote our cover story on Gustavo Dudamel in 2013. She had embarked on a piece about Eddie Redmayne (page 96). “I realise most actors are far from your Platonic ideal, being pr’d to within an inch of their lives,” she wrote, “but Eddie is a different kettle of fish – clever & thoughtful, and he has had this extraordinary year playing Stephen Hawking for ‘The Theory of Everything’, for which I’ve been quietly observing him at close quarters...” Quietly observing: that sounded like us. Clemency’s piece is not a profile of Redmayne, although you get to know him reasonably well by the end of it: it’s the story of a project. In a telling moment, he talks about being at Cambridge, where he read history of art and used to rub shoulders with the engineering students, whose faculty was next door. Redmayne felt bad because he and his arts mates worked far less than the engineers, yet they would all end up with “a number, a degree”. (The difference comes at the end of the rainbow, where the engineers find a pot of job security.) His own grasp of science, he admits, was faint: he had to have some of Hawking’s theories explained to him as if to a six-year-old. But in the way he applied himself to capturing the remorseless onset of Motor Neurone Disease, he turns out to have been a fine student of biology. “The second a muscle goes,” he says, “it can’t come back again in a different scene. It’s not something the director can fudge in the edit.” By interviewing Redmayne several times, never in a hotel room, let alone with a pr hovering, Burton-Hill gets under the skin of a formidable piece of work. In our other long reads, the two cultures go their separate ways. Good riddance (page 76), by Tom Whipple, is the story of a doctor, Donald Hopkins, who has helped to eradicate one disease and is tanta-

12

lisingly close to vanquishing another – a particularly nasty one, as you will discover. The storysellers (page 66) is a piece of mine on three projects, two in Britain, one from New Zealand, that foster literacy and creativity. It was prompted by two moments in 2010: a sneak preview of a new museum in Oxford, and a trip to a school quiz in Edinburgh, in which my daughter took part. All three projects are heartening, inspiring and rather under-sung. Perhaps some of those actors’ publicists will see an opportunity to branch out. Our photo essay (page 84), often a set of landscapes, is a set of portraits this time: music-lovers with their first vinyl record, by Dean Belcher. We note that records are like kisses, in that you don’t forget your first. More than that, the memory can make you smile or cringe. Many of Belcher’s subjects stand there with a big smile on their face. My own first record is a cringe: “Long Haired Lover from Liverpool” by Little Jimmy Osmond. I was ten; he was nine. I confessed this in an e-mail to Laura Barton, whose words accompany the pictures. “A very fine choice!” she replied. “Mine was ‘La Bamba’ by Los Lobos, bought at Woolworth’s in Holyhead with a 50p-off voucher from Smash Hits. Rest in peace, some of those things.” The British Society of Magazine Editors’ Awards are coming up. We have a nomination for the magazine as a whole, and one for Columnist of the Year: Robert Macfarlane for Landscapes of the Mind (page 130). You can tell a lot about a magazine by its back page, and Rob has made ours sing with his blend of erudition and warmth – and a helping hand from Su Blackwell, whose paper sculptures, made from the book Rob is writing about, are an unfailing delight. ~ Tim de lisle

subs CRIBE

&SAVE

UPTO

44%

ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTIONS FROM JUST £24

An Economist Group business

EDITOR Tim de Lisle

PUBLISHER Nick Blunden

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Daniel Franklin

HEAD OF SALES Laura Morris

DEPUTY EDITOR Isabel Lloyd

LIFESTYLE MANAGERS Katie Hooper Ben Sharpington

MANAGING EDITOR Ingrid Esling ART DIRECTOR Graham Black DEPUTY ART DIRECTOR Martin Lovelock PICTURE EDITOR Melanie Grant ASSISTANT EDITOR Samantha Weinberg LITERARY EDITOR Maggie Fergusson DIGITAL EDITOR Simon Willis DEPUTY DIGITAL EDITOR Lucy Farmer ASSOCIATE EDITORS Rebecca Willis Robert Butler CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Julie Kavanagh (culture) Kassia St Clair (style) Melanie Grant (jewellery) LETTERS EDITOR & EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Charlie McCann FACT CHECKER Andrew Gilbert

SUBSCRIBE ONLINE AT

POST PRODUCTION Dexter Premedia Noel Allen

and enter TCGH or call +44 (0)114 220 2404 and quote TCGH

INTERNS Tom Graham Jainnie Cho

www.economistsubscriptions.com/intlife

CONTINENTAL EUROPE ~ PUBLISHER Myriam Vergne CONTINENTAL EUROPE ~ SALES MANAGER Romain de Lestapis USA ~ SENIOR VICEPRESIDENT David Kaye HK ~ SALES MANAGER Charlotte Fearnside ADVERTISING MARKETING Darren Smith CIRCULATION AND MARKETING DIRECTORS Mark Beard Marina Haydn OPERATIONS DIRECTOR Jamie Credland MARKETING MANAGER Caroline Carter SYNDICATION AND LICENSING Jennifer Batchelor Sarah Van Kirk PRODUCTION Faye Jeacocke Simon Maggs Andrew Rollings

intelligentlife@economist.com 25 St James’s Street, London SW1A 1HG +44 (0)20 7830 7000 FOR ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES UK +44 (0)20 7576 8113 CEMEA +33 (1)53 93 67 19 ONLINE moreintelligentlife.com Twitter.com/IntLifeMag facebook.com/intelligentlifemagazine EDITOR-IN-CHIEF OF THE ECONOMIST John Micklethwait

17

CONTRIBUTORS

LAURA BARTON (Photo Essay, page 84) is a Guardian feature writer and car reviewer. Her first novel is “Twenty-One Locks”.

ARIANNA HUFFINGTON (Big Question, page 38) is the author of “Thrive” and founder of the Huffington Post.

ADAM NICOLSON (Big Question, page 38) has written 20 books, including the Samuel Johnson-longlisted “The Mighty Dead”.

ISABEL BEST (Lipsmacking, page 36) writes for Elle and the ft. She lives in Paris.

ALAN JOHNSON (Big Question, page 38) is a Labour mp who has held five cabinet posts. His books are “Please, Mr Postman” and the Orwell prize-winning “This Boy”.

RUTH PADEL (poetry rocks, page 48) is a poet, memoirist and the Royal Opera House’s first writer-in-residence.

CLEMENCY BURTON-HILL (Redmayne, page 96) is a bbc Radio 3 presenter, violinist, actress and writer. Her latest novel is “All the Things You Are”. SWITHUN COOPER (poetry rocks, page 48) has published poems in Poetry London and the Rialto and won an Eric Gregory award. IMTIAZ DHARKER (poetry rocks, page 48) is an artist, film-maker and poet. “Over the Moon” is her latest volume of poetry. ANNE ENRIGHT (Big Question, page 38) is the author of “The Forgotten Waltz” and the Booker prize-winning “The Gathering”. TOM GRAHAM (Notes on a Voice, page 112) is our latest intern. He is reading biomedical sciences at New College, Oxford. DAVID HARSENT (poetry rocks, page 48) is the author of “Fire Songs” and “Night”, which won the Griffin poetry prize. CHRISTOPHER HIRST (Kitchen Dialogues, page 36) is a former Food Writer of the Year and the author of “Love Bites”. JOHN HOOPER (digital humanities, page 30) is The Economist’s Italy correspondent.

Shelf-educated Books by our contributors

16

LUCY KELLAWAY (Big Question, page 38) is the ft’s management columnist and the author of “In Office Hours”. CHARLES LAURENCE (Caribbean, page 116) is the author of “The Social Agent” and a former correspondent for the Daily Telegraph. He divides his time between New York and the Turks and Caicos. KIERAN LONG (Built to Last, page 62) is senior curator of contemporary architecture, design and digital at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. ROBERT MACFARLANE (Landscapes, page 130) teaches English at Cambridge and chaired the 2013 Man Booker prize judges. His books include “The Old Ways”. HENRY MARSH (Big Question, page 38) is a neurosurgeon and the author of “Do No Harm”, which was longlisted for this year’s Samuel Johnson prize. CLAIRE MESSUD (Authors on Museums, page 106) is the author of the New York Times bestseller “The Emperor’s Children” and, more recently, “The Woman Upstairs”.

JASPER REES (Visual CV, page 114) is an author and writer for the Sunday Times, the Daily Telegraph and theartsdesk.com. FIONA SAMPSON (poetry rocks, page 48) is professor of poetry at the University of Roehampton and the author of “Coleshill”. TAIYE SELASI (My Madeleine, page 35) is the author of “Bye-Bye, Babar (Or: What is an Afropolitan?)” and “Ghana Must Go”. TOM SHONE (Cinema, page 111) is a professor of film history at nyu and the author of “Martin Scorsese: A Retrospective”. MICHAEL SYMMONS ROBERTS (poetry rocks, page 48) is a Costa award-winning poet and the author of “Drysalter”. TOM WHIPPLE (eradicating disease, page 76) is the science correspondent of the Times. PAUL WHITFIELD (When In..., page 122) is the co-author of the original edition of “The Rough Guide to New Zealand”. HENRY WISMAYER (Wild Things, page 128) writes for National Geographic Traveler, Conde Nast Traveller and Wanderlust.

W W W. ZENITH-WATCHES .COM | W W W. ROLLINGSTONES .COM

F

O

L

L

O

W

Y

O

U

R

O

EL PRIMERO CHRONOMASTER 1969 T R I B U T E TO T H E R O L L I N G S TO N E S

W

N

S

T

A

R

LETTERS

CRISIS? WHAT CRISIS? Re: The kilogram (Intelligence, September/October) Tom Whipple’s report on the demise of the physical kilogram reminded me of the weeks leading up to the new millennium. Media hype was fuelling public fear about the “y2k crisis” and I was on assignment in Canada to assess how it might impact the National Research Council’s laboratories. An nrc director assured me that the press had it wrong; the computer glitches had been fixed long ago. But nrc scientists at the Institute for National Measurement Standards in Ottawa were far less relaxed. In winter, temperatures can plummet to -45°C and they feared for the heating systems. In the vault containing the Canadian kilogram, a drop of one or two degrees might cause it to lose enough “weight” to disqualify it from the global system of official measures. If that was the nrc’s biggest worry, I felt Canada could weather y2k quite comfortably. MARILYN SMITH, PARIS

A good man to hand Re: Jean of Ark (Features, July/August) Maggie Fergusson’s article about Jean Vanier moved me for two reasons. First, it highlighted how Christianity – the genuine kind, not the indoctrinated sort – can be turned to the service of mankind. To read this gives me hope. Second, it reminded me of the day I held the hand of Jean Vanier. He had come to meet the residents of AlKafaát, the mission set up by my father to care for those with disabilities. This was during the darkest years of the war in Lebanon. My father and Jean were worlds apart, but their faith in man was the same. In the company of the most “marginal” members of society, the people afflicted with the severest of disabilities, they both found God. And so did I. MYRIAM SHWAYRI, BEIRUT

18

where to be with the ball, without the ball and in relation to others on the pitch. They were much better “interpreters of space”. RICHARD VAUGHTON, FRANCE

The big omission Re: The Big Question (Intelligence, September/October)

Space cadets Re: Reading the Game (Intelligence, September/October) In the 1970s I coached an under-19s football team in Lancashire. Most of the squad was made up of a-level students, but some of the players had left school when they turned 16. Many of the latter were so good, they were attached to pro clubs. But it was noticeable that the more students I played, the more successful the team. The students had less technical ability, but they better understood the requirements of team play; they knew

The range of views aired in “What’s the point?” was curiously incomplete. Why wasn’t a religious perspective included? Today it’s accepted that faith is foolish. But over millennia, countless individuals have found a raison d’etre through religion. These people built empires, discovered gravity, painted masterpieces. Were they fools?

HAVE YOUR SAY E-mail us at intelligentlife@economist.com or post a letter to The Editor Intelligent Life 25 St James’s Street London SW1A 1HG Please include your name, location and e-mail address. Letters may be edited for reasons of space or clarity.

THE POINT OF LIFE IS...CONSCIOUSNESS What’s the point? It might be the biggest question of them all. Puzzled over with a furrowed brow or flung out with an expletive, it’s also one of the most flighty. We challenged seven writers to pin it down and explain the meaning of life, and then THE BIG QUESTION invited readers to vote for the best answer in our online poll. For Philip Pullman, the purpose of life is consciousness; the more of it we have, “the better we’re able to understand, create and be kind”. He won the day with 29% of the vote. The Economist’s obituarist Ann Wroe was more succinct, saying, simply, “The point is love”: her share of the vote (23%) far outstripped her word count. The novelist Yiyun Li drew on Seneca and Charlie Brown to make the case for living in the moment, and came in third with 11%. The philosopher Mary Midgley persuaded 7% of the voters that not only does life have a point (take that, Richard Dawkins), it consists in seeking “a larger perspective”. Elizabeth Kolbert, the New Yorker writer, and John Burnside, the poet, tied at 6%. For him, imagination creates meaning; for her, the point is to pass on our genes. Some 4% sided with Stephen Grosz, the psychoanalyst, who felt that the point was to alleviate suffering. Many readers contributed their own views (see “The big omission”, above). But one wrote “All of the above”. Point taken. ~ CHARLIE McCANN The next Big Question What’s the best escape? Page 38

CREDIT WHERE IT’S DUE

THIS SEASON

Exhibitions

Rodin in his lab, facing both ways

Le Baiser (marbre) dans l’atelier du Dépôt des marbres / photographe: Eugène Druet, V&A

Rodin’s figures have a restless energy. Lean, long-limbed, they stretch and slump, curl and clinch. Unlike that of his friend Monet, his rise to fame was a slow burn. It took critics years to give him the recognition he deserved and he still splits the crowd today. Is it because he is a tricky artist to pigeonhole? Rodin was both a champion of modern art and a by-product of the late Romantics. He looked behind him for inspiration. He was fascinated by ancient Greek mythology and spent long periods obsessing over literary epics such as Dante’s “Inferno” and Baudelaire’s “Les Fleurs du Mal”. But he looked forward too, rebelling against traditional methods, finding new ways to work that blazed the trail for modern sculpture. His work is not about familiar iconography or textbook perfection, but a strong desire to capture the inner truths and troubles of the human soul. His world runs on passion and turmoil. “The Laboratory of Creation”, the Musée Rodin’s final show this year, is an unusual one. With hardly any finished bronzes

Exhibitions AT A GLANCE Allen Jones (Royal Academy, London, Nov 13th to Jan 25th). The RA continues its knack for finding well-known artists who have never had a British retrospective. Allen Jones’s pop art is full of colour and irony, and his drawings are worth a closer look. Pop to Popism (Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, Nov 1st to Mar 1st). A chance to see some of Australia’s finest pop artists alongside the usual suspects. Look out for “The American Dream” by Brett Whiteley – at 22 metres long, it’s hard to miss. Drawn by Light: The Royal Photographic Society Collection (Science Museum, London, Dec 2nd to Mar 1st). A dive into the archives of the world’s oldest photographic society, from William Henry Fox Talbot to Martin Parr – plus a range of gadgets including Nicéphore Niépce’s heliograph. Love is Enough: William Morris and Andy Warhol (Modern Art Oxford, Dec 6th to March 8th). Guest-curated by the 2004 Turner prize-winner, Jeremy Deller, who puts Morris and Warhol head to head. Soul

on display, “we’re focusing on the things we don’t usually show – the different steps and studies, the sketches before the masterpiece,” says Hélène Marraud, co-curator of the exhibition. Here, the weight will fall on Rodin’s plaster and terracotta casts: a huge collection that will be shown alongside his drawings. Irregular, rough and smothered in fingerprints, the casts offer a glimpse into Rodin’s creative process. Less polished than his bronzes, they have an expressive power that is authentic and undiluted, and shows Rodin at his best. Look at “Meditation”, 1896. The female figure is hunched; she meanders left, then right, and the surface is covered in pits and pocks. The details are unrefined, but Rodin has captured the true spirit and sensuality of his model. He has given her an emotional intensity that is both tender and authoritative, full of grace and full of strength. I’m booking my ticket now. ~ OLIVIA WEINBERG Rodin: The Laboratory of Creation Musée Rodin, Paris, Nov 13th to Sept 27th 2015

mates or a relationship doomed from the start? You decide. Francis Bacon: The Process of Creation (Hermitage, St Petersburg, Dec 7th to March 8th). A dense but focused show that positions Bacon alongside his influences: Rembrandt, Titian, Van Gogh, Picasso. It goes to the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich next year. Small Stories: At home in a dolls’ house (V&A Museum of Childhood, London, Dec 13th to Sept 6th). Funny little figures, lovably dated wallpaper: it’s hard to resist a dolls’ house. Here are 12 spanning 300 years, including a kitsch “Kaleidoscope House” by Laurie Simmons. Giovanni Battista Piranesi (National Gallery, Prague, Nov 21st to Feb 1st). Piranesi was one of the great printmakers. His imaginary prisons and ancient ruins inspired everyone from Coleridge to Victor Hugo. Delacroix’s Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (LACMA, LA, Nov 16th to Feb 15th). A whole exhibition about one painting, from 1826. Packed with history, it depicts Greece as a young woman with fiery eyes and a troubled gaze. ~ OW

23

THIS SEASON

24

Theatre

Mr Norris changes jobs Rufus Norris, who takes over as artistic director of the National Theatre in London next April, was nearly an actor. Nearly a successful actor, in fact: he trained at rada, and has the kind of lowering good looks – Mr Rochester by way of Easter Island – that would have guaranteed him at least a few interesting auditions. But in his early days hanging out at Arts Threshold, a fringe theatre in west London, he was told he was “too gobby” to be an actor, and so he switched to running the show instead – a change of pace for which we should be grateful. In person he’s restrained, thoughtful, ever so slightly intimidating. And his shows reflect a similar, serious intellectual engagement – he has said, with some moral urgency, that his job is “telling stories, and getting at the truth”. Yet, like his slightly younger contemporary Rupert Goold (42 to Norris’s 49), he is a highly theatrical theatre director: his productions are multi-layered, exuberant, brimming with visual inventiveness. The difference is that Goold’s inventiveness sometimes seems to run riot for its own sake; Norris’s serves the show. There have been several notable high points in a career with almost as many peaks as the Himalayas: a stripped-back, pulsating staging of Thomas Vinterberg’s 1998 Dogme film “Festen” for the Almeida in 2004; a joyful, playful adaptation of DBC Pierre’s novel “Vernon God Little” for the Young Vic in 2007; and “London Road” at the National in 2011, which dealt with the Ipswich murders and singlehandedly created a new form – the verbatim musical. “Behind the Beautiful Forevers”, David Hare’s adaptation of Katherine Boo’s award-winning non-fiction narrative about slum-dwellers in Mumbai, seems right up his street: rich with life and voices of all kinds, ranging far beyond the fourth wall, telling a story people need to hear. It opens at the National shortly, and as a statement of intent for the Norris regime, it’s a good omen. ~ ISABEL LLOYD Behind the Beautiful Forevers Olivier, London, Nov 10th to Jan 14th

The Guardian

Theatre AT A GLANCE Golem (Young Vic, London, Dec 9th to Jan 17th). The animationand-live-theatre specialists 1927 return to London with a new show, a modern take on the Jewish monster myth that should play strongly to their aesthetic – part Terry Gilliam, part Fritz Lang. Another Place (Theatre Royal, Plymouth, Nov 6th-22nd). A new play from D.C. Moore exploring man’s obsession with wanting to be elsewhere – in this case outer space. No cast yet, but the Theatre Royal has produced a string of excellent shows lately, including Edward Petherbridge in “My Perfect Mind” (touring until Nov 21st). Constellations (Samuel J. Friedman, New York, from Dec 16th). Lucky New York, part one: Nick Payne’s sharply etched, deeply affecting two-hander about memory and loss was one of the standouts of the Royal Court’s 2012 season. Its Broadway premiere has Jake Gyllenhaal as the alternatively hapless and hopeful hero. A Particle of Dread (Alice Griffin, New York, from Nov 11th). Lucky New York, part two: Stephen Rae and Lloyd Hutchinson reprise their roles in this Sam Shepard reworking of “Oedipus Rex”, first seen – and praised – at last year’s Derry/ Londonderry City of Culture. Assassins (Menier, London, Nov 21st to Mar 7th). Jamie Lloyd continues his bid to have a show playing in every postcode in London. The comedy-heavy casting – Catherine Tate, Mike McShane, Andy Nyman – says he’ll be pointing up the satire in Sondheim’s killer musical. Swallows and Amazons (Old Vic, Bristol, Nov 27th to Jan 17th). A welcome revival of Tom Morris’s sophisticated, energetic adaptation of the Arthur Ransome novels: aside from Bryony Lavery’s reboot of “Treasure Island” at the National, if you want to avoid trad panto, this is the best bet for children this winter. ~ Il

THIS SEASON

Classical

Good reverberations At 56 going on 26, the Finnish conductor-composer Esa-Pekka Salonen continues to make waves. His concern for the environment manifests itself every year in his Baltic Sea festival, and his determination to embrace technological advances keeps finding new and original outlets. Last year the interactive classical-music app he co-created won a Royal Philharmonic Society award for reaching new audiences, and this year he has been part of a commercial advertising campaign to promote classical music along with Apple’s iPad Air. He’s still doing his bit as a cheerleader for more conventional events, though always with an invigorating twist. The concert series he’s launching at the Southbank is a case in point. Entitled “City of Light: Paris 1900-1950”, it draws in two of the most versatile pianists in the game – Mitsuko Uchida and Pierre-Laurent Aimard – and one of the most flamboyantly brilliant sopranos, Barbara Hannigan. Starting with Debussy’s “Pelléas et Mélisande” and moving on via Stravinsky and Ravel to Messiaen’s “Turangalila”, these concerts reflect a musical revolution which, in Salonen’s view, is still reverberating today. ~ Michael Church City of Light: Paris 1900-1950 Southbank Centre, from Nov 27th

Talks

To Vancouver with love Vancouver in the fall means sunglasses and umbrellas – you either get gilded autumn colours, or you get soaked. But for six days in October the Vancouver Writers Fest offers an excuse to take cover, while listening to authors from across Canada and beyond: this year’s crop includes James Ellroy, Tim Winton, Karl Ove Knausgaard and Eimear McBride (left). The venue is Granville Island, actually a peninsula, an industrial wasteland now transformed into a waterfront haven for lovers of the arts and esoteric food. The Fest offers some enticing combinations in its biggest programme to date: Emma Donoghue with Sarah Waters; Esther Freud and Herman Koch with Christos Tsiolkas. Two popular regular features are the Sunday Brunch (readings, croissants, Buck’s Fizz) and the Literary Cabaret, in which six authors perform and a band tailors music to their texts. The “Fitting Finale” lives up to its name, pairing the intense but twinkling Colm Tóibín and the quietly mischievous Jane Smiley. ~ anthony gardner Vancouver Writers Fest Oct 21st-26th; writersfest.bc.ca

26

talks AT A GLANCE Cambridge Literary Festival (Nov 30th). One packed day, with Ali Smith, Marina Warner, John Boyne and Alan Johnson. Sarah Waters, DBC Pierre and Kim Newman (British Library, London, Dec 3rd). Three spookophile novelists discuss Gothic literature. UEA Literary Festival (Norwich, to Nov 26th). Weekly talks featuring Ian McEwan, Jane Smiley, Richard Holmes. Hay Festival Dhaka (Bangla Academy, Nov 20th-22nd). Nadeem Aslam, Romesh Gunesekera and Aamer Hussein are among the writers, graphic artists and activists making Hay in Bangladesh. Richard Ford (Carnegie Hall, Pittsburgh, Dec 8th). A titan of contemporary fiction. ~ ag

The Guardian, Arena Pal

CLASSICAL AT A GLANCE The Makropulos Affair (Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich, Oct 19th). Nadja Michael is the heroine in a new production by Arpad Schilling, with Pavel Cernoch as Albert Gregor, and Tara Erraught (the centre of a critical row at Glyndebourne) as the bewitching Christa. Carmen (from the Met, New York, Nov 1st). Richard Eyre’s popular production goes to 2,000 theatres in 66 countries. L’elisir d’amore (Royal Opera, London, Nov 18th). A revival of Donizetti’s comic masterpiece with Lucy Crowe, Bryn Terfel and the new tenor sensation Vittorio Grigolo. But the biggest draw is Laurent Pelly’s charming off-the-wall production. Les Arts Florissants (Cité de la musique, Paris, Nov 21st-22nd). William Christie’s superb ensemble mark 250 years since Jean-Philippe Rameau’s death with rare airings of two of his Fontainebleau divertissements. The Gospel According to the Other Mary (ENO, London, Nov 21st). Peter Sellars premieres John Adams’s latest opera – “an extraordinary work”, says the New York Times. ~ mc

M ESUR E ET D ÉMESUR E *

TONDA 1950

Rose gold Ultra-thin automatic movement Hermès alligator strap Made in Switzerland

www.parmigiani.ch

THIS SEASON

ROCK AT A GLANCE David Bowie (album, Nov 17th). This should be the best Bowie compilation since the cool calm clarity of “ChangesOneBowie” . Drily entitled “Nothing Has Changed”, it comes in three versions: a triple CD, in reverse chronological order; a double CD, in chronological order; and a double LP, all shook up. All three include one new song, “Sue (Or In a Season of Crime)”. Bryan Ferry (album, Nov 17th). Bowie and Ferry on the same day: is this 1973 all over again? After “The Jazz Age”, Ferry strolls back to the present. Or perhaps the more recent past – his title, “Avonmore”, clearly summons the ghost of “Avalon”. Stevie Wonder (N. American tour, Nov 6th to Dec 5th). Lately he has had more misses than hits, but this could be fabulous: the classic album “Songs in the Key of Life”, in full, featuring “As”, “I Wish” and the king of all, “Sir Duke”. ~ tim de lisle

ROCK

Dancing his way out of obscurity This has been Future Islands’ year. Just before the release of their fourth album “Singles” in March, they performed on the “Late Show with David Letterman”. By September, Samuel T. Herring’s impassioned performance of a pulsating synth ode to waning love called “Seasons (Waiting On You)” had been viewed 2.5m times on YouTube. Instantly, Future Islands were dragged from dive-bar obscurity into the powerful currents of the mainstream. While plenty of bands might have burned up in the mania of media sensationalism, here was one that had been honing a style for nigh on ten years by the time they were caught in the lights. To see them in concert is to know this. Herring’s moves fall somewhere between Morrissey and a Butlins Redcoat: muscular, limber-limbed, with a pantomime intensity that makes it hard to look anywhere else. His bassist, William Cashion, maintains a thousand-yard stare that is comic by comparison. Together with a keyboard player and a touring drummer, they put on a show worth a hundred Letterman slots. It draws heavily on Future Islands’ earlier, dancier material, giving Herring ammunition for routines that inspire feverish dancing on the floor. A reminder that, while it may take years to learn how to manhandle the mood of a crowd, in 2014 it only takes one four-minute clip to change the course of a career overnight. ~ HAZEL SHEFFIELD Singles out now. Future Islands on tour Europe, Oct 3rd to Nov 8th; LA, Nov 20th

All songs at iTunes and Spotify (search IntLifeMag)

Jeffrey R. Staab

iNTELLIGENT TUNES: SIX GOOD SONGS TO SLIP INTO YOUR POCKET Jamie T: Zombie. Ed Sheeran for grown-ups. Or, if you prefer, Joe Strummer for the young. Leonard Cohen: A Street. One of six gems on “Popular Problems”, the best album ever by an octogenarian. U2: Every Breaking Wave. Never mind that intrusive iTunes giveaway, here’s what they do best: rock with soul. Robert Plant: A Stolen Kiss. From an album full of hefty riffs, a moment of beautiful restraint. Jessie Ware: Pieces. After making it mediumsized in 2012 with her crisp electro-soul, Ware now has the lungs and lustre of a star. ~ tDl

FILM

To sleep, perchance to dream, in Turkey When you watch a Nuri Bilge Ceylan film, you’re transported to a distant land. In literal terms, that land encompasses the windswept steppes and looming mountains of the Turkish countryside, territory which this writer-director made his own in his hugely acclaimed, hypnotic crime odyssey, “Once Upon a Time in Anatolia”. It’s a terrain of wild horses and humanoid rock formations – a fantastic setting which could double as an alien planet or an elvish kingdom without any assistance from cgi. But Ceylan’s Anatolia isn’t just defined by its geographical wonders. Its dreamlike atmosphere is even more distinctive. His new film, “Winter Sleep”, won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. It’s a Chekhovian drama, partly based on Chekhov’s short stories

FILM AT A GLANCE Interstellar (Nov 7th). Christopher Nolan’s “Inception” attracted Kubrick comparisons by the dozen. There’ll be dozens more when he sends Matthew McConaughey to the other side of the universe. Life Itself (Nov 14th). Despite their invaluable contribution to society, film critics aren’t often internationally loved Pulitzer prize-winners. The late Roger Ebert was. “Life Itself”, a documentary adapted from his autobiography, conveys the humanity, erudition, pointed humour and joie de vivre which some film critics may lack.

The Drop (Nov 14th). Tom Hardy pours the drinks in a Brooklyn “drop bar” where ill-gotten gains are stashed. Scripted by Dennis Lehane (“Mystic River”), this downbeat gangland drama is a chance to raise a glass to Hardy’s co-star, James Gandolfini, who gives a fine final performance. The Imitation Game (Nov 14th). This classy biopic can’t quite solve the enigma of Alan Turing, but Benedict Cumberbatch (right) excels as yet another of his buttoned-up, socially inept geniuses, and he gets Best-ofBritish support from Keira Knightley, Matthew Goode,

and revolving around a complacent hotelier (Haluk Bilginer), his bitter sister (Demet Akbag), and his frustrated, much younger wife (Melisa Sözen; exquisitely nuanced performances, all). Their cave-like hotel seems to be a cosily beautiful haven, but when the tourist season ends, and there are fewer guests to distract them, they start to feel trapped in an exasperating limbo, somewhere between the 21st century and the Middle Ages. Whatever they do, mysteries aren’t quite solved, logic doesn’t quite apply, and philosophical conversations spiral and swirl, without ever reaching a conclusion. Pay them a visit for 200 minutes, and the rest of the world will seem far away. ~ nicholas barber Winter Sleep opens in Britain Nov 21st

Rory Kinnear and Mark Strong. What We Do in the Shadows (Nov 21st). Jemaine Clement, the bespectacled half of Flight of the Conchords, co-writes and stars in the year’s funniest film, a mock-doc about a group of diffident vampires sharing a house in New Zealand. It’s the “Spinal Tap” of horror movies. Exodus: Gods and Kings (Dec 26th). Ridley Scott breaks out the swords and sandals again, which might just mean a return to “Gladiator” form. Moses and Rhamses are played by the controversially un-Egyptian Christian Bale and Joel Edgerton. ~ NB

29

Rewriting history Received wisdom on the Grand Tour in 18th-century Europe is being transformed by 21st-century techniques in California. John Hooper meets the academics who are leading the way In the centre of Stanford University’s sprawling campus stands an impressive clock tower. Through glass at the base you can admire its complex, early20th-century mechanism and read the time from a little clock face that replicates the bigger one above. Next to it, someone has thought to place an even smaller, digital clock. So people know the real time. Stanford, the university that gave birth to Silicon Valley, is probably the world’s least analogue seat of learning. Hewlett-Packard, Google, Cisco Systems, Yahoo, PayPal, Sun Microsystems and Instagram were all founded by its alumni. So it is not surprising that Stanford should also be at the heart of a movement that has swept across campuses in recent years with the speed – and, some would say, the destructiveness – of the forest fires that break out in the hills above the Santa Clara valley. Digital humanities, still relatively little-known beyond academia, involves using information technology to study the arts and social sciences. Depending on how you define it, the term can encompass anything from building a computer-generated, threedimensional representation of an ancient Sumerian city to feeding thousands of 19th-century novels through software to count the number of words for moral qualities and then sort them by author, date or whatever criteria you choose to put in. Visualising the results of the analysis on, say, an interactive chart or map, is crucial to most digitalhumanities projects: it can enable researchers to draw at a glance conclusions that would otherwise lie unnoticed in a morass of facts and figures. “It’s wonderful to have the data at your fingertips, to bounce the facts around in a way that would be impossible without computers,” says Giovanna Ceserani. Over lunch in the Stanford Faculty Club, she produces a laptop to explain what she means. Ceserani is studying the 18th-century Grand Tour. Her database is John Ingamells’s “Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers to Italy, 1701-1800”, a storehouse of information on more than 5,000 men and women who journeyed through Italy in search of education, inspiration or, sometimes, just entertainment. Ceserani has narrowed her gaze to the 69 who became architects.

“Even so,” she says, “it is impossible to remember all that is known about all of them.” Tapping on the keyboard, Ceserani summons up a bar chart. Beside the vertical axis are the names of her subjects. The horizontal axis measures the number of months they spent in Italy. Multi-coloured bars stretching from left to right show where they stayed, each separate colour corresponding to a town or city. One colour predominates: red, for Rome. That of itself is no surprise. The ruins of the old imperial city were the high point of the Grand Tour. But when Ceserani ran the same exercise for the aristocrats with an interest in architecture, she discovered something that would never have struck her just reading through the entries in Ingamells’s monumental directory. “The amateurs, like Lord Burlington,” she says, “went as much to Venice or Naples as they did to Rome.” The data, when visualised, showed that a long stint in Rome was a kind of litmus test: “It almost defined what being an architect in the 18th century was all about.” Prompted by what she had seen in the bar chart, Ceserani began looking again at the architects’ relationship with Rome. What she found using conventional research techniques was that “it was not just about looking at great old buildings. Rome was a unique place where you could interact with people from other countries and social classes, sometimes gaining patronage in the process.” And not only that: Ceserani’s non-digital studies showed that the aspiring British and Irish architects were far more engaged with their Italian contemporaries than had been realised. They studied under masters like the great engraver Giovanni Battista Piranesi; they tried to join Italian architectural societies and win Italian architectural competitions. “When the Architects’ Club, England’s first architectural association, was founded in 1791,” Ceserani says, “one of the four requirements was to belong to an Italian academy.” Her project is an example of the way digital humanities should work. Prompted by an original view of data that had long since been available, she formed a hypothesis that inspired her to look at the literature in a new light. In this case, the hypothesis

© VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM, LONDON

INTELLIGENCE

RESEARCH

is one that challenges the view of the Grand Tour as a jaunt for dilettantes. For architects at least, says Ceserani, “it was where professionalisation took place.” With its palm trees, courtyards and artificially weathered sandstone masonry topped with red tiles, much of Stanford looks the way a Moorish palace might do in a video game. On the top floor of a building in this distinctive, Beau-Geste-on-the-West-Coast style is the Centre for Spatial and Textual Analysis, or cesta, the inter-departmental unit that is digital humanities’ most important bridgehead on campus. Ask Mark Algee-Hewitt, a lecturer from the English faculty, whether cesta could fairly be described as the epicentre of the worldwide digital humanities movement, and he replies with a smile and a “we like to think so.” Behind him is an array of filing cabinets

marked “Chinese Railroad Workers”. More than 10,000 Chinese toiled to build America’s first transcontinental railway, many of them in the employ of Leland Stanford, the founder of the university that bears his name. The mostly illiterate Chinese left behind little by way of diaries or memoirs. But one use of digital humanities can be to fill in the void where no written accounts exist. cesta’s researchers are mining corporate and other records to build up a picture of the lives of the Chinese who helped to unite America. In some cases, the work carried out at cesta merely confirms what might have been assumed. Was it really worth running large numbers of texts through computers to show that the term “United States” was more often followed by a verb in the plural (“the United States are...”) before the civil war than after it? In other cases, however, digital research can yield >

When in Rome... ...do as the techies do: the Piazza Navona (1756) by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, with a modern twist

31

> evidence that undermines, or even destroys, accepted

Untold stories Chinese labourers building the Northern Pacific Railroad in Western Montana in the 1870s, employed by Leland Stanford, who also founded the university

32

theories and common assumptions. cesta’s biggest project is Mapping the Republic of Letters, a catch-all title for a series of studies, including Ceserani’s, that aim to shed light on the internet of the Enlightenment: the network of correspondence that linked intellectuals in the 17th and 18th centuries. “We’re like the nsa,” says Dan Edelstein, a professor of French. “We look at who wrote to whom, when and where.” An obvious target for this form of surveillance was Voltaire. Among his many contributions to the Enlightenment was his “Lettres Philosophiques”, published in 1734, which he claimed introduced Locke to a French readership. Voltaire had lived in Britain for three years and spoke English. So when Edelstein first looked at the visualisation of his correspondence, “what jumped out at me was that Voltaire wrote so little to Britain. There were only 140 letters out of a total of around 15,000 – less than 1%.” Edelstein went back to examining Voltaire’s correspondence and realised for the first time the rel-

evance of his subject’s attachment to the notion of translatio studii – the idea that the centre of civilisation moves inexorably from place to place. “Essentially, Voltaire thought England had had its moment in the historical sun,” says Edelstein, who based a research paper on his findings. Caroline Winterer, a professor of history and director of the Stanford Humanities Centre, had a similar eureka moment when she saw a map of Voltaire’s correspondence set alongside that of her main subject, Benjamin Franklin (engraving, right). “With Franklin what you get is a dense transatlantic network,” she says, “whereas with Voltaire there is just one letter that crosses the Atlantic.” That seemed to justify Franklin’s fame as a cosmopolite. But when Winterer dug deeper into the data there was another surprise waiting: “most of his correspondents were either British or American.” This is a recurrent theme in the Republic of Letters project. The networks of the intellectuals of the Enlightenment were far more restricted than the academics had imagined. Paula Findlen, a professor of Italian history, says the same was true of Galileo. “We think of him today as perhaps the first scientific celebrity. But he lived in a relatively local world until he was forced not to.” It was only after this great polymath came under the menacing gaze of the Inquisition that he reached out for help to non-Italian intellectuals. “In 1597, Kepler writes to him and sends him one of his books,” Findlen reports. “Galileo responds politely, but no great intellectual camaraderie comes of it. He does not get back to him until 1610, when he has need of him.” “You’re not plugging in data to get answers,” says Winterer, “but to ask better questions.”And some of those questions remain tantalisingly unanswered. A pioneer of digital humanities – and one of its most controversial figures – is to be found in a darkened study, piled high with books, not far from cesta’s headquarters. Franco Moretti, Stanford’s professor of English and Comparative Literature, was drawn into digital humanities by way of cartography. He set out to produce an atlas of the European novel, which was published in Italian in 1997. “I realised that to make good maps you need sets of data,” he says. “That is how I started quantifying.” One of his projects involved analysing all the passages in 19th-century novels that begin 50 words before a place name and end 50 words after it, with the aim of determining the place’s emotional associations. Analysing the results, Moretti noticed something that he had not set out to find: “The growth of fictional London did not match the growth of real London.”

Corbis, AKG

intelligence

The population exploded in the 19th century, growing from 1m to almost 7m. Yet for the most part British authors continued stubbornly to locate the events in their novels in a London that stretched from “somewhere near the Bank of England to Mayfair”. Yet, says Moretti, the same is not true of French authors writing about Paris. Why not? “Is it perhaps that in London the chic areas have not changed?” he asks with a shrug. “I just don’t know.” The person credited with inventing digital humanities was yet another Italian. In 1949, Father Roberto Busa, a Jesuit priest who was bent on compiling a concordance of the works of St Thomas Aquinas, persuaded ibm to let him use its punch-card technology, then at the cutting edge. Busa said later that after learning that an in-house report had concluded his project was impossible, he went into a meeting with ibm’s founder, Thomas J. Watson senior, carrying one of the firm’s own posters. It bore the slogan “The difficult we do right away; the impossible takes a little longer”. Watson was won over, but the impos-

Great minds Among those whose letters have been analysed are Benjamin Franklin (holding wreath) and Voltaire (back, third from left). Joseph Louis Masquelier’s 1791 engraving pictures the moment when Mirabeau handed the new French constitution to Rousseau

At Stanford, science students refer to the nonscientists as fuzzies

sible did indeed take longer. The last of the 56 volumes of Busa’s “Index Thomisticus” was published in 1980. By then punch-cards had given way to magnetic tape, which had given way to floppy disks. But it was the advent of the world wide web in 1991 that really enabled digital humanities to take off. For Caroline Winterer, as a university administrator, one of the benefits of digital humanities is that it breaks down barriers between disciplines. These are traditionally formidable at Stanford, where students reading science subjects – techies – refer to their non-scientific fellowundergraduates as fuzzies. “Humanists have always worked alone, like monks in cells,” Winterer says. “Digital humanities involves publishing together and, before that, thinking together. cesta crosses the barrier between techies and fuzzies.” But, for its critics, all this quantifying, this computing and classifying, not only runs counter to the spirit of disciplines that deal in shades of meaning, but could give students the idea that they no longer need to read, see and listen. Caroline Winterer says she understands the concerns. “Some of the values that we try to cultivate are taste, discrimination and aesthetic appreciation, and those are not obvious targets for digital humanities. There is no substitute for the kind of deep knowledge that only long-term immersion can bring. Digital humanities can enhance that, but not replace it. People still need to read books, look at pictures and listen to music.” Franco Moretti, who coined the term “distant reading” to describe the computer analysis of literary works, is public enemy number one for the traditionalists. His “penchant for playing devil’s advocate”, one critic argued, “has brought him as close to notorious stardom as his discipline allows.” This affable Italian clearly takes a mischievous delight in provoking outrage, coming out with remarks such as: “There is no continuity between reading and knowing.” Some of the experiments planned under his overall direction in cesta’s Literary Lab are enough to prompt a shudder of apprehension in the least technophobic of bookworms. One of them aims to establish >

Tim Atkin The Wine-List Inspector

At a former television factory in Beijing, you’ll find wine that deserves an Emmy > whether there is something linguistic that excites sus-

pense in readers. “We’re talking to social psychology about it,” says Algee-Hewitt in a matter-of-fact way. The project would involve volunteers, he says. “We want to hook them up to machines like lie detectors, to see if their heart rates change in response to certain words and phrases.” Might that not be the first step on a road that could one day lead to the formulation of an algorithm for the writing of the perfect, definitive – and last ever – suspense novel? “It’s never that easy,” Algee-Hewitt retorts. “I doubt we’ll ever – I hope we’ll never – reach that point.” Like Moretti, he insists that, within the rapidly evolving world of digital humanities, Stanford is a bastion of moderation: that those who teach the technique on campus accept that quantitative analysis has to go hand in hand with traditional methods. “Some of the younger people are tempted by the strength and purity of numbers to think that formal methods should just be forgotten,” Moretti says. “I think that is a mistake.” Put to him the view that his methods could deter people from reading, and he replies with a question: “Have you visited the Stanford Bookstore?” I had, and it had been a sobering experience: the huge window display running the width of the store – packed with cards, mugs and sweatshirts – found room for only 12 books. Half of them were frivolous. Of the other six, one was “Are you Smart Enough to Work at Google?” Inside, books occupied less than half the floor space. The section on Japanese history – a subject of no small importance to a Pacific coast university, you might think – offered only seven titles. At the campus Starbucks, 17 students were using laptops, and one was reading a book. Stanford provides a glimpse of an almost book-less future. “I am the only member of my family who still reads books,” says Moretti glumly. From the vantage point of Silicon Valley, digital humanities can be seen, not as an attack on the arts and social sciences, but a pre-emptive rescue: a way of making them attractive and comprehensible to a generation brought up on Facebook and Twitter. What none of those involved in digital humanities disputes is that the discipline is in its infancy. As the software for interrogating data becomes more widely available, as libraries and archives digitise more of the books and manuscripts in their possession and make the texts available to scrutiny by outsiders, the possibilities for quantitative investigation will increase exponentially. With a metaphor of which any man of letters would approve, Franco Moretti says: “This is just the first chapter.” ■

It’s not easy being a wine lover in Beijing. You’d expect this thrusting capital to be full of vinous delights, especially at a time when China is supposed to be enjoying a wine boom. But beer and baijiu, the local grainbased spirit, are both much more popular, and most restaurants serving Chinese cuisine don’t take wine seriously. If you want to drink decent wine, opt for Western menus. The best of these (and the one with the most interesting wine list) is at Temple Restaurant, widely known as TRB. Located in the old Dongcheng district, close to the Forbidden City, it’s housed in a former black-andwhite-television factory. Yet there’s nothing monochrome about the food. The four-course tasting menu we enjoyed – with two choices per course, for 458 yuan (€58) – was French-inspired, but not afraid to include coconut curry, bok choy or Beijing camembert. The owner, Ignace Leclair, is a Belgian who knows his wines. His extensive, well-chosen list features selections from more than a dozen countries, including China. Given that locals make up 75% of TRB’s clientele, this may seem a politic move, but apparently it’s the foreigners who tend to order the Chinese wines.

The list, like the food, focuses on France, particularly the classic regions of Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne and the Rhône, but there is an eclectic line-up from other regions and countries, too, many of them made using organic or biodynamic methods. The tasting menu comes with the option of four different glasses for an extra 268 yuan, all of them European (presumably because there are only seven Chinese wines on a list of more than 400), but as there was such an intriguing range from farther afield we ordered by the bottle instead. Our table ordered several different dishes, so I picked two versatile, unoaked wines. From Spain, the 2012 Terras Gauda O’Rosal, Rías Baixas (488 yuan) was a crisp, focused, stony white that was the perfect foil for the seafood starters, while the Sicilian 2012 Arianna Occhipinti Tami Frappato (380 yuan) was the sort of chilled, juicy, refreshing red that worked equally well with riceflake crusted lobster and duck confit. And the Beijing camembert? Monsieur Leclair suggested a savoury, bone-dry, umami-rich González Byass Leonor 12 Años Palo Cortado Sherry. The match, like everything else at TRB, was spot on. trb-cn.com; 726 yuan pp, including wine

Where else to go and what to drink ARIA At the China World hotel, an awardwinning, high-end list to complement food from the Australian chef Phillip Taylor. Around 600 yuan pp Best white: 2012 Neil Ellis Groenekloof Sauvignon Blanc South Africa has made enormous strides with the Sauvignon grape thanks to the development of cool-climate areas such as Groenekloof. New Zealand Sauvignon meets Sancerre. 350 yuan Best red: 2010 J. Palacios Pétalos, Bierzo A delicious example of Spain’s indigenous Mencia, grown in the hills of Bierzo. A rich yet refreshing red with notes of plum and green pepper, and a touch of oak sweetness. 700 yuan shangri-la.com/beijing/chinaworld

ILLUSTRATION CHRIS PRICE

HERITAGE A recently updated, cosmopolitan wine list matches the classic French cuisine at the Sofitel Wanda hotel. Around 400 yuan pp Best white: 2011 Howard Park Riesling, Great Southern A bone-dry Riesling from Western Australia. On the cusp of developing some bottle-aged characters, but it’s also brimming with limey zip and acidity. 490 yuan Best red: 2010 Craggy Range Sophia, Hawke’s Bay A delicious, finely wrought Bordeaux blend that deserves the same accolades as the better-known Craggy Range Syrah. Subtle notes of red berries and graphite, and well integrated oak. 900 yuan sofitel.com

INTELLIGENCE

MY MADELEINE

The loving spoonful As a pleased-with-herself graduate, Taiye Selasi thought she knew it all. But Ghana, and a bowl of soup, taught her otherwise In 2001, over the course of the summer, my godmother taught me to cook. I’d just graduated phi beta kappa from Yale. My mother was thrilled. My godmother, less. My education, however prestigious, was patently incomplete. I could write in Yoruba, translate Latin, pick a horse hoof, play piano, spot a Botticelli – but, for shame, I couldn’t cook. The solution was simple: I would go to Ghana for a culinary apprenticeship, living in my godmother’s house while studying in her kitchen. My godmother, like my mother, is an extraordinary cook. One of those rare human beings who, in the words of a friend, “seem to put air” into food. I’d long since marvelled at the magic she produced out of Ghana’s culinary canon, transforming into gourmet meals the fare of farmers and fishermen. There was her famously velvety garden-egg soup – an eggplant dish like caponata; her gingery “red-red”, a tomatobased stew of onions and black-eyed peas; her palava sauce, a delicious mix of leafy greens and fresh smoked fish; but above all there was her groundnut soup, that creamy dream of a stew. Groundnut soup is held to be a national dish of Ghana, though our Senegalese neighbours claim the same of mafé, an identical stew. The titular groundnuts – what Americans call peanuts – are roasted and ground into butter, then blended with the standard west African tomato-and-onion base. It was an ambitious dish with which to start my course in domestication. But my godmother, unlike my mother, is a wonderful teacher. If I’d come to Accra an ignorant cook, I was an educated eater, raised on my mother’s dazzling brand of international cuisine. My mother is the type of cook who never needs a recipe, whose units of measurement are “handful”, “pinch”, and “until it just tastes right”. But between her roles as single mother, doctor and gourmet chef, she simply never had the chance to give lessons. To study under my godmother was another thing entirely, as much to do with being in Ghana as with being instructed. For the groundnut soup we used ripe tomatoes plucked from her lush garden. We bought peanuts from the women who harvested them, grinding them ourselves. We knew the names of the market vendors and chatted with each about what was in season, buying enough to last for

the week. In short, we gave food time. The onions in Ghana, small and red, were incredible to begin with; my godmother’s painstakingly slow sweating method turned them into candy. Blended with fiery Scotch Bonnet peppers, ginger and tomato, the onions gave the groundnut soup a sweetly smoky taste. We let the pot simmer, for eternity it seemed, until oil from the peanut butter rose to the top, breaking out in little puddles like oil spills on a lake. I must have mastered 30 different dishes that one summer. My godmother, having lived across Europe and Africa, cooked everything – and everything well. We made chana masala, Yorkshire pudding, marmalade, ratatouille. But my favourite dish, which became my best, is still her groundnut soup. Learning to cook Ghana’s national dish was an object lesson in Ghanaian living: in seasons, farming, respect for nature, family values, patience. Ten years later when I moved to Rome I’d re-encounter those lessons, discovering a culinary culture very similar to Ghana’s. In Italy people still shop at markets, know their vendors, grow their herbs. And whenever I entertain in Rome I make my favourite soup. The tradition began in September 2012 when a friend and I hosted dinner. As happens on weeknights only in Rome, our guest list numbered 40. I went to Piazza Vittorio to buy the rice and pepper. My friend ground the pounds of peanuts at home. We picked tomatoes from the terrace. The soup was a success; it has become an annual tradition. Every autumn I make a pot, and tell my friends to bring friends. Patiently waiting for the oil to surface, as if the peanut butter were releasing its ghost, I think about my education in my godmother’s kitchen. To cook for others is not, as I thought when I went to her that summer, an exercise in anachronism, in notions of female duty. To cook is to connect. With nature, with land, with history, with culture. With people. This was my godmother’s lesson – indeed, her lasting gift – to me. ■

Street life The author in Ghana, where her godmother taught her to shop locally, and to “put air” into food

35

INTELLIGENCE

Hirst & Schon The Kitchen Dialogues

A food writer from Yorkshire, a chef from France, a conversation about cooking

ON THE MENU

36

LIPSMACKING

Toasted truffle sandwich Michel Rostang, Paris As the food arrives, all conversation stops. Compared with the precisely assembled amuse-gueules handed to other diners, four triangles of sandwich with a pile of curly endive at their centre hardly look spectacular. But the scent – earthy, organic – is almost overwhelming; enough to stifle the bourgeois lunchtime chatter at Michel Rostang’s restaurant here in the 17th arrondissement. Rostang’s black-truffle sandwich is renowned throughout Paris, the most popular item on his winter truffle menu, yet also the simplest. You could make one at home, but go instead chez Rostang for the care he takes with ingredients. The salted butter is churned to order in Brittany, the sourdough is custommade at Boulangerie Poujauran with a particularly aerated crumb that soaks up fat like a sponge, while the black truffles come direct from a renowned market in Richerenches, Provence. “The chef recommends you eat with your fingers,” commands the priestly, black-clad waiter. I pick up a triangle, golden brown on the outside, slivered with black between. First comes the crunch of toast, steeped in salty hot butter, which through some kind of osmosis has drawn into itself both the tang of sourdough and the perfumed essence of fungi. Then comes the chew of the truffles themselves, surprisingly meek after the buttery fanfare to which they have yielded their souls. And that butter – it doesn’t so much ooze out of the bread’s pores as gush, sliding over my fingers. For €65 you can buy the truffle sandwich as a takeaway, to store in the freezer and toast at home. Apparently one customer buys six at a time. I wonder if they eat them all at once? ~ ISABE L BE ST €98; michelrostang.com

PORTRAITS BY MAJA DANIELS, ILLUSTRATION BY HOLLY EXLEY

“The lentil is one of my favourite pulses,” said massively different – and I try all the time for Arnaud Schon. “Puy lentil hummus is terrific.” My quality. It’s hard to find really good fillet.” second conversation with the freelance French The potato-and-celeriac galette presented chef who cooks at The Economist concerned an less of a problem. “You just grate and mix the two evening meal he made for the magazine’s board of vegetables, squeeze out the water, season and fry directors. It turned out that we were both great in clarified butter, like a rosti. It should be crunchy fans of the Puy lentil. Since I once visited Le on the outside and a little bit mushy inside. Butter Puy-en-Velay, south-west of Lyon, to report on is essential.” these tiny AOC-protected treasures, I was able to I was reminded of the great French chef chip in – or, to be more accurate, show off. Fernand Point, who explained “the secret of good “It’s the volcanic soil that makes them cooking” in a New Yorker article from 1949 as “Du different. You can see the volcanic cones of the beurre, du beurre, du buerre.” But this being 2014, area on the label of Volvic water. It’s ironic, but Arnaud is somewhat more restrained. “The thing Puy farmers are not allowed to water their lentils about butter is it tastes great. Every morning, I – the plants have to fight for nutrition. It’s what have my toast and the butter oozes and smears gives them their flavour.” over my face. It’s fantastic but it’s the only fat I eat “Really?” But Arnaud was keen to get back to all day, more or less.” his starter. “I sautéed them with a mirepoix [finely A week before we met, I mentioned to chopped celery, carrots and onion in the Arnaud that I’d never had apple Charlotte so he proportions 1:1:2] until they were al dente. Puy surprised me with one specially baked for our lentils are different from chat. But, ever the ordinary lentils – they keep perfectionist, he tutted at their shape while cooking.” the result. “It’s not cooked “Yes, did you know that quite enough,” he said, our word ‘lens’ came from peering at the pale brown ‘lentil’?” dome of cooked sliced “Ah. Then I finish them bread with its filling of Puy lentil salad with a light dressing of red sautéed apple. “Coxes are a wine vinegar with salt, bit sweet. I usually use a with red mullet pepper and a little oil. mixture of Bramleys and Vinegar and lentils are a Coxes.” It tasted fine to me; fantastic combination. Try it. but I admitted that I’d made Beef fillet, potatoI had it a lot when I was a my first apple Charlotte child. When I taste it, I’m five only the previous night. It and-celeriac galette years old again.” had the right, dark-brown An amateur chef might colour – or at least, it have the idea of combining matched the photo in the strong, gamey flavour of Arnaud’s battered college Apple Charlotte fried red mullet with earthy textbook, “Travaux lentils but he wouldn’t think Pratiques de Cuisine”. I let of using a ring-mould to slip the secret of my shape the pile of pulses. At accidental success: “I used least this one wouldn’t. And sliced brioche for the crust he wouldn’t dream of sprinkling cubes of acidic – I think the sugar in the loaf caramelised a bit.” Granny Smith apple between the disc of lentils Arnaud instantly saw the possibility. “Yes. It and fillet of mullet. “I discovered a few years ago could be really good, like using panettone in a that raw apple goes so well with fish or shellfish,” bread-and-butter pudding.” Arnaud explained. “God that sounds good. Bread-and-butter The main course prompted an admission. “It’s pudding is my favourite.” the first time I’ve done beef fillet in two years. I’m “I top it with a marmalade glaze. You just not too keen on this piece of meat. It should have brush it over, including the peel, when the great marbling of fat and be dry-aged [hung pudding comes out of the oven.” unwrapped in a cold store]. The fillet from my “Hmm. Sounds a bit like gilding the lily.” supplier was OK but it was wet-aged, in a vacuum “Eh?” pack.” Suppliers prefer wet ageing because It could have been the phrase “gilding the dry-aged beef loses 30% of its weight over a lily” that puzzled Arnaud. Or it might have month. “It’s already an expensive piece of meat been my inbred Yorkshire preference for but it’s still more when it’s dry-aged. The quality is plainness. I couldn’t say. ■

INTELLIGENCE

What’s the best escape

THE BIG QUESTION

When life is fraught, should you empty your mind, or engage it elsewhere? Six writers choose a way to zone out ANNE ENRIGHT NOVELIST “My Body is a Cage”, goes the song by Arcade Fire: the problem is getting out of there without letting the door slam behind you, because the greatest escape of all, unfortunately, is death. There are day passes, of course: drugs, dissociative states, psychosis. There is alcohol and sex, also meditation, the endorphin rush of exercise, the top of the mountain and the freewheel cycle downhill. Let us not forget poetry, the touch of someone you love; there is, when you think about it, love itself. But so effortful all of them, so exhausting, this battle through the ego to escape the ego, this pushing of the body to be free of the body, when all you really have to do to escape your sad sack of bones and flesh is take your clothes off, walk into the sea, and splash. It has to be the sea because the sea holds you up. It also slaps you and throws you about a bit, requiring your admiration, gratitude and respect. The sea is plentiful and cheap; you are, when you swim in it,

connected to every other beach and rock you swam from over the years. It has to be the sea because there, chopped about by the advancing waves, is the horizon, and this does some secret, muscular thing to your gaze. After five minutes’ swimming towards it, your brain will open: simple as a window in the month of May. It helps if the water is cold. It helps if the water is frightening; if you escape grabbing weed and the idea of jellyfish, if you turn from that grey harbour seal, with the neck of a nightclub bouncer and the eyes of a lover. You should come out of the sea as from a close encounter with the fearful and the strange; your flesh condensed by the cold, grazed by rocks, you should be bleeding quietly and freely from your big toe. After which you turn to look back at the beautiful water, remembering how you felt when you had nowhere to stand, and that was just fine.

HENRY MARSH NEUROSURGEON AND AUTHOR The London hospital where I work is seven minutes by bicycle from my home and I consider myself to be permanently on call for my patients. So in a sense I can never escape, unless I leave the country, and even then I am pursued on my mobile phone. But in fact I escape every day since my house has a little garden looking out onto a small local park, and at the end of the garden I have built a workshop with elaborate red wooden pillars in imitation of the Forbidden City in Beijing. The garden I leave largely to itself, so it is a managed wilderness of flowering bushes and tall hollyhocks, with a resident fox whom I tolerate provided she doesn’t dig too many holes in the flowerbeds. There were four fox cubs last year. The wisteria at the front of the house has grown over the roof and a noisy family of sparrows lives in the eaves (along with some squirrels whom I recently evicted), and this spring there was a blackbird nesting on the security light over the front door and a wren by the kitchen window. I ILLUSTRATIONS BILL BUTCHER

keep bees in the garden. They swarm regularly into my neighbour Selwyn’s garden, but he puts up with the invasions with good humour. He will ring me up if I am in the hospital, and I will cycle back as soon as I can and with a cardboard box climb up to wherever the swarm has settled, catch it, and return to work. I started making furniture when I was an impoverished medical student. My wife and I did not have a table so I made one from an old packing case. The only tools I had were a saw and a hammer. My brother admired it and asked me if I’d make one for him, and I said I would, for the price of a plane. Forty years later I have accumulated a huge collection of tools and have made many tables, beds, chests and other pieces (the early ones not very well, I must admit). I’m currently working on an oak table for one of my daughters. This is rather different from brain surgery. For a start, wooden joints don’t heal (but nor do they bleed), and the physical manipulations involved are entirely different – although not when sawing open the bone of the skull. There is the same joy in using your hands in a useful way but without all the anxieties. Neurosurgery is always dangerous, and operations often fail, with awful consequences for patients and their families, for which I cannot help but feel responsible. At least with woodwork the only risk is to my self-esteem, and an occasional bruised finger. The workshop looks out onto the garden and I spend two to three hours every evening making furniture or sharpening my tools, thinking only about the job in front of me, at home in my little demiparadise. Rus in urbe.

ARIANNA HUFFINGTON PUBLISHER AND AUTHOR “Onward, upward, and inward” is my favourite motto. And inward is my favourite escape. What makes it all the more special is that going inward is both an escape and the ultimate reality. I completely get the sense of wonder that has led men and women through the ages to explore outer space, but personally I have always been much more fascinated with exploring

inner space. There is, of course, a connection between the two. Astronauts have often reported transformational experiences when they have looked back at Earth, a phenomenon that has been called “the overview effect”. But, as Thomas Merton put it, “What can we gain by sailing to the Moon if we are not able to cross the abyss that separates us from ourselves? This is the most important of all voyages of discovery, and without it all the rest are not only useless but disastrous.” Marcus Aurelius called that place I love escaping to our “inner citadel”. And, being both the emperor of Rome and a Stoic philosopher, he clearly demonstrated that you could escape into your inner citadel and rule an empire at the same time. You can be “in the world, but not of the world”. What is beyond doubt is that I, like most of us, spend most of my life outside that citadel. The key for me is quickly course-correcting – sometimes ten minutes of meditation or even a moment of conscious breathing is all it takes. I try to do it daily, working it in wherever I find myself – at the office, in a hotel, on an aeroplane (where it can be done even when the person in front of you reclines their seat). The aim is that as I grow older I can get better at escaping back into that place of stillness, imperturbability and grace, until it becomes second nature quickly to escape to what is actually our true nature. And there’s a bonus: this escape requires no passport, no planning ahead and no leaving home. >

39

INTELLIGENCE

> ADAM NICOLSON

AUTHOR AND BROADCASTER The best moment is always just after the beginning. I have a small boat nowadays, just under 16 feet long, and it is not the sort of boat people usually ooh and aah about. There’s nothing wooden in it, no delicious, polished spars. It has an aluminium mast and a fibreglass hull and all sorts of snap shackles and jamming cleats. So although I love the way all this works, sailing for me is not a kit thing. It is more about what happens when you get it all to go. I almost always sail alone, launching from a beach, and as I push off, jump in, lower the daggerboard, grab the helm, harden up the sheets and feel the wind coming and going on the skin of my cheek, it’s then that the miracle happens: all the elements that on land had seemed half-chaotic, banging here and there, too complicated to be coherent, suddenly come into a perfect, steady relationship — with each other and with you. The sails fill, acquire their beautiful, held-bosom shape, the boat heels away from the wind, you lean out against it, tiller in one hand, mainsheet in the other, and, in that most expressive of sailing terms, you and the boat start to gather way.

The wake begins to bloom behind you; the cockpit drains gurgle; the bow-wave lifts and runs the length of the hull. In a dinghy, your own body is the governing counterpoise to the pressure of the wind on the sails, and that maybe is at the heart of why this is the greatest of escapes: there is no sitting back here. This is not an escape at all, but a plunging-in, a total immersion of mind and body in the ways of wind and sea, needing a small amount of skill maybe, but more than that a high attentiveness, a precision alertness to how things are, to the tide running around you, the shape of the gusts coming down off the hills, the rolling of the swell. That is what small boat sailing gives you: intimacy with the reality of the world.