The inflorescence of Fascicularia bicolor with its blue flowers. The center of the foliage on a blooming rosette, turns red when the flowers appear and then, like many Bromeliad, that rosette dies replaced be previously formed offsets. My blooming plant had multiple rosettes at the time, three of which bloomed. Taken in my garden, Sept. of ’17.

If you’re not into blood and guts, consider this genus, as on my scale of one to ten as described above with ten warning of near complete evisceration if one is fool hardy or reckless, this one’s a solid 4, dangerous enough but not stupidly so. Fascicularia pitcairniifolia. You would think that in a genus composed of one or two species things would be pretty well settled taxonomically, guess again. Originally described as F. bicolor it was reclassified as F. pitcairnifolia and later changed back to F. bicolor. Subspecies were proposed. Changes retracted. There are significant differences in the sampled populations, but were they sufficient to constitute separate species??? Adding confusion at a different level are those who say the species name indicates that it is from Pitcairn Island. It is not. The specific epithet simply recognizes a similarity to the foliage in genus, Pitcairnia, another Bromeliad member. This Fascicularia is from the lower Chilean Andes, allegedly north of the other Fascicuaria species, F. bicolor which is suppose to be slightly hardier and occurs at least occasionally as an epiphyte! Some botanists have argued that F. pitcairnifolia possesses thicker, slightly wider leaves. and some minor differences in the timing of flowering and is reputedly slightly less hardy. The ranges of both overlap Good luck sorting this out.

They say that there is no shame in trying, that the shame is in avoiding the challenge…don’t they say this? Well, I bought this one from Sean, in 2012. Grew it in a pot for awhile and then planted it out in ‘13 on my east facing retaining wall, a rotting old RxR tie affair. My plant failed to grow the following spring. [trans. it died.] It’s demise is recorded in my database, winter of ’14. What happened to it?

That winter our temperatures dropped five times down into freezing temperatures, each time for several days in row. Over two of those periods, one in early December the airport dropped to 12º and another in early February, when we dropped down to about 20º. At the same time we recorded sub-freezing highs with our usual pattern of at least several days above normal high temperatures in-between, before freezing, even lightly again. In other words, the typical yo-yoing that we get that can wreak havoc with a plant’s dormancy making them more subject to damage or death. The rain year measured from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30 was 5” below normal. So, what killed it? Some growers in England say that with excellent drainage, these can go as low as 14ºF. Well, mine was planted in the local loam right next to the wall, but it was likely still too wet. Wet or cold? They tend to compound the negative effects of each other. I won’t be trying that again without a backup plant in a pot and I won’t try it unless I’m planting into scree or a well constructed crevice bed.

I bought a Fascicularia bicolor ssp. caniculata ‘Spinners Form’ in June of ’14 as a replacement. I potted it up a couple times in consecutive years leading into the summer of ’17. I plant it in my typical mix with added pumice making it nearly half pumice. Once every couple weeks I set it in a tray to bottom water it along with a ‘squirt’ to the top. Sometimes I’ll give it an additional squirt between these more thorough soakings. This is the schedule I follow with many of my potted succulents, though I avoid the top watering of those that the practice encourages fungal growth on. Watch and learn. This seems to work well for my more ‘arid’ terrestrial Bromeliads.

Zona Sur, or the Lake District, is depicted in light green on the map. 45º latitude, comparable to Portland, OR is just south of its southern border. Doing the ‘hemispheric flip’ would place Zona Sur along the central Oregon coast down into the northern California coast. The weather patterns and coastal currents are very similar, but the differences in land masses, and mountains result in different growing regions. The west coast of Chile of Zona Sur and on south is characterized by hundreds of islands, bays, inlets and fjords. The Zona Australe shares much with the coast of British Columbia.

Fascicularia bicolor grows primarily in scree, but can be found as an epiphyte in Chile south of Santiago in the Lake District, or Zona Sur. Chile, a very long narrow country, is divided into 5 different biological regions north to south with widely varying climates, the huge Atacama Desert, considered the driest desert in the world, stretching 600 miles from Peru on Chile’s northern boundary, south, lying within the area colored ‘coral’ to the left. Zona Sur lies between, Zona Central, the native range of several of the dryland Puya spp. Zona Sur begins at the Rio Bio Bio. Zona Australe is to its south, which includes the remote and cold southlands of Patagonia, the division being at the Chaco Channel; the Pacific is the obvious western boundary and the Andes and Argentina are to the east. The Zona Sur and Australe are deeply scarred by glaciation and can be characterized by abundant rivers and lakes sliced through by channels and fingers of saltwater. Chile’s Central Valley slopes southerly down down through the Zona Sur from into an inland sea, the Golfo de Ancud. Geologically it is a volcanic region with well drained soils and scattered younger peaks standing well above the eroded ridges and mountains. The climate is Valdivian Temperate Rainforest, extending well easterly into the mountains with rainfall totals from 100″- 200″. As you might guess temperatures tend to be moderate/cool. It lies between 37º S and 43.4ºS latitude and has strong seasonal westerly winds, not unlike our condition here along the Oregon and Washington coast. This forested country is dominated by southern hemisphere conifers and both evergreen and deciduous Nothofagus trees along with Myrtles. There are forests of Aurucaria and Fitzroya as well as large wetlands. Unlike the Puya, Fascicularia spp. are not arid region plants. They can often be found growing on trees or cliff faces where water doesn’t collect, draining and percolating quickly away. It is humid country. Some growers have recommended keeping it out of direct or intense sun which is probably more important if your summer temps trend above 85ºF. I move my pots around and none of them get full afternoon sun though they can get a couple hours at mid-day. With free draining or scree I might be tempted to grow this in the ground, I might even try it in a shadier portion of my front retaining wall once it bulks up. Overhead protection, canopy, could be of help as well.

To better understand the scale of a place like Chile I include this. Chile is 2,356 miles long north to south and averages 177 miles east to west. Here the mapmakers have rotated Chile 90º overlaying in on the US. Both are drawn to the same scale. Zona Sur, on this map, would cover Chile from central ‘Wyoming’ to central ‘South Dakota’. Santiago, the capital in central Chile, is at 33ºS latitude which would put it just south of Los Angeles in the Northern Hemisphere. Were Chile stretched out along the coast of North America it would reach from about 18ºN to 55ºN, roughly from almost Acapulco, Mexico, almost to Ketchikan, Alaska. Spanning such a distance north and south suggests how diverse its climates are. Add to this the ruggedness of the country, and the Andes with an average elevation of 13,000′ and you get an even clear picture of its differences. It is also interesting to note that Chile contains some 5,100 different species of plant almost half of which are endemic, occurring no place else on earth.

My friend, Mike, has been having some success growing this in the ground here in SE Portland where it is planted on a slight north slope at the edge of an old large, topiary chicken! Yes, a chicken…of the Boxwood type. It has been there only a year (spring ’19), so the verdict is not yet completely in. It would seem that as these mature and produce offsets the bulking up aids a bit in their hardiness and tolerance. Some others have suggested to me that these are somewhat temperamental and don’t divide them….I think that difficulties with division might have more to do with the timing and after care. When I divided mine each plant had very few roots. I would suggest doing what I didn’t do…I tore my entire plant apart rather than just a few offsets and the old spent rosettes…the result of which will be that it will be likely two years or so before I see flowering again. Didn’t really think that one through. I pin these in place to stabilize them as I’ve done when dividing other Bromeliaceae. For a simple how to and confidence builder, check out this video produced by Burnacose Nurseriers in the UK. Of course the larger the plant you are dividing, the more rosettes it has, makes this more of a physical challenge in addition to the issue of their lightly barbed leaf margins, perfect for tearing skin, which she doesn’t mention. They suggest doing so in winter but they have heated glasshouses and I do not. My basement can get quite cool in winter, down to 55ºF which will slow rooting.

One reason for dividing them, beyond their getting large and congested, is that over the years the rosettes begin to flower, which is what we want, but the old inflorescences remain attached turning brown quickly, tightly nested in the base of the old rosette while it slowly declines. Like many Bromeliads this is monocarpic so the result will be old browning rosettes amongst your fresh, un-flowered, green ones. In a small pot or when viewing up close, this is an aesthetic negative, so I chose to divide, this time not doing so until the early summer of ’18. I wanted time for the plants to be able to anchor themselves before going into winter when moving the pots around you could disturb the slow growing roots.

Ochagavia carnea and Fascicularia inflorescences are very similar, which is consistent with their very similar genetics arising within the same ‘clade’ or genetic line….Individual flowers are around 3″ long and are packed tightly into a head, the inflorescence, which can be around 4″ across and tall.

A quick overview: the Bromeliad family is limited to the western hemisphere, the bulk of member species native to South America. There are 23 species of Bromeliaceae in Chile, twenty of which are endemic. The three species of Tillandsia found in Chile are not endemic. The local genus includes T. usneoides, Spanish Moss occurs commonly across much of the wider range of Bromeliads into North America. Fascicularia spp. and the Ochagavia spp. have very limited ranges and are endemic to their regions discussed here in Chile. Ochagavia include four species. O. andina, which as it’s name suggests, is a resident of the Andes, limited to a small area in Central Chile, in lowlands and valleys, from 2,300′ up to 8,000′ or the limit of occasional snowfall, well away from the coast. It is thought to be hardy to brief freezes of 23ºF, though relatively little is known of it as it is relatively rarely observed in the field O. litoralis, as it’s specific epithet suggests, is limited to the mild coastal region of central Chile where it grows above the heavy salt spray to 800′, saxicolous, on rock. O. lindleyana…I couldn’t find much on this species and, some don’t recognize it, would seem to have a very limited range, to below the line of snowfall in the Valpariso region, just north of Santiago. Other sources recognize O. elegans which has the most geographically limited range occurring only on the cliffs of Isla Robinson Crusoe of Juan Fernandez Archipelago where it is quite common, forming dense stands by offsetting freely.

I helped another friend divide a Bromeliad, I was told was an Ochagavia carnea, she had on ‘loan’ so three of us could each have a healthy sized piece. She hadn’t divided any of the Bromeliads before, I think also that she wanted to avoid any confrontations with the spiny margins. So I did it, happy to then have a plant of my own. Later I was told, by a knowledgeable third party, that this was in fact another form of Fascicularia bicolor!!! Apparently there is quite a range in the width and length of the leaf blades, as to my eye the plants looked significantly different. Ochagavia carnea has strappy leaves that can grow up to a meter in length, but can be, I found, half that. My plant currently needs up potting as it is very crowded, its leaves are limited to about 18″….The article, “Revision of the genus Ochagavia (Bromeliaceae, Bromelioideae)”, Georg Zizka, Katja Trumpler, and Otto Zöllner published by the Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum, Berlin, acknowledges the confusion both between and within these two genera. It would seem that there is work yet to do by the botanical specialists!…The only thing left for me to do is to grow them both out to blooming and then make a determination!!! Okay!

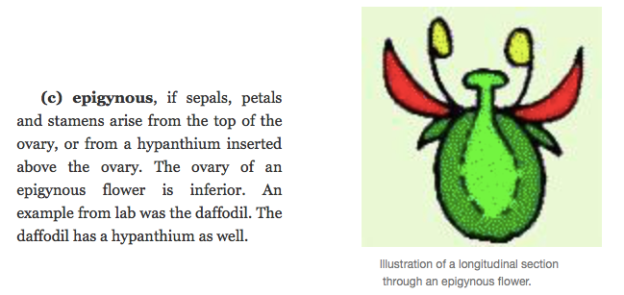

From the UBC Biology 343 Blog. The epigynous tube is the style with the stigma atop it. In Ochagavia spp. the center tube is as much as three times as long as the stamen, the reverse of the relationship shown above.

Ochagavia carnea individual flower. In the drawing (a) you can see the defining, exserted, style and stigma rising above the stamen. Taken from the above referenced paper from Botanical Garden and Museum Berlin.

Their inflorescences are similar in structure but the base of the leaves of the flowering rosette on O. c. turn pinkish, rather than the vibrant crimson red hue of the Fascicularia in question, with much less of the leave’s bases changing color. What botanists use to define the four Ochagavia spp. apart from each other most accurately are the comparative lengths of the stamen and pistil structures, notably, their prominent epigynous tube, as there is considerable overlap of their other structures. On Ochagavia spp. the epigynous tube can be as long as .75″, as much three times the length of the surrounding stamen. The Fascicularia bicolor and Ochagavia carnea have somewhat different flowers, blue verses pink, with slightly different sized petals, overall, their petals separate, overlapping at the base, with all of their parts in multiples of three, consistent with the flowers of all Monocots. Shouldn’t I be able to tell them apart? It is also interesting to note that the finer textured F.b. ‘Spinners Form’ flowered within 3 years of my purchasing it, bulking up quickly over the period. The coarser/larger O.carnea I have has bulked up quickly as well, though not to its described maximum mature size and has not flowered. I should note here that gardening experience in southern Europe, even on the island of Siciley, where O. carnea has naturalized to an extent, have been observed to rarely flower! Time to move on.

O. carnea is found frequently across its range within Central Chile, generally from 500′- 3,000′, away from the coast itself, but throughout the coastal mountains and on into the interior valleys of the Andes, occasionally higher up to the line of snowfall, north to the region of Valparaiso, above Santiago, and south to the Rio Bio Bio where the Zona Sur begins. It tends to occur as a component of sclerophyllous forest, comparable the California’s chaparral, or temperate deciduous forest in the southern portion of its range. They are most often found on rocky banks of streams and ravines, but can be found growing on a variety of sites from south facing, to flat, to north facing where they are protected from more intense sun. It would appear that this is the most moisture friendly of the genus. There is overlap of their range with several of the arid Puya species though the Puya are found on hotter more exposed sites. It is said to be tolerant of light freezes to -3ºC, but intolerant of snow accumulation. It is not found at all in the wet Valdivian Rainforest of the Zona Sur to the south. Across its range rainfall is in a mediterranean pattern and these are well adapted to 4-5 months of summertime drought, receiving between 15″- 31″ of rain over an average year. Some gardeners claim this is hardy to USDA zn9, or 20ºF, if its moisture and drainage requirements are met.

My plant spends most of our winters outside. I leave it on the porch where it can get rain, slide it under the roof if we’re going to have a light freeze and move it into the basement if its supposed to drop into the mid-20’s or lower. I’ll also move it under the roof when we’re in an extended period of heavy rain, keeping in mind that some years we can get nearly double their maximum rainfall these get in their native range.

Fascicularia is found more commonly in the cooler, wetter south of the Zona Sur, but the Fascicularia does range into at least the southern portion of the Central Zone where rainfall is lighter, so I can see how this physical overlap combined with morphological variations in these species can complicate field ID and a collector’s duty.

A brief update: we’re coming into spring of ’19 and the ‘Ochagavia’, or whatever it is, has increased in mass adding more rosettes to its bulk…but it still hasn’t flowered! I should pot it up and give the new mix a little slow release as the old soil is not doubt completely spent. Maybe it will bloom this summer, ’19???

Here’s a link to the larger article that this was originally a part of, “Bromeliaceae and Dangerous Plants: Adaptation, Climate Change and Gardening in Portland“.

You should eat the fruit, they are called chupones in Chile and apply to several bromeliads :)

LikeLike