Here’s something in full for once, rather than just a link. I wrote a large feature on Clive Barker’s Nightbreed for the September 2012 issue of Empire, and this is the full transcript of the interview I conducted with Barker, in which he talks in detail about Nightbreed, its source novel Cabal, and the new “Cabal Cut” of the film.

For those new to the story, Nightbreed was taken away from Barker and re-cut by its studio for release, to the extent that Barker more-or-less disowned it. The cut footage was thought lost, but various work-prints have been uncovered on VHS tapes over the last couple of years. This footage was then assembled into what is essentially a bootleg cut, dubbed The Cabal Cut, by Derby-based academic and filmmaker (and friend of Barker’s) Russell Cherrington, Mark Miller of Barker’s Seraphim Films company, and editor Jimmi Johnson. With Morgan Creek’s support, Nightbreed: The Cabal Cut has been regularly playing on the festival circuit and at one-off screenings ever since, and is edging towards a full restoration and DVD/Blu-ray release. You can follow its progress at Occupy Midian.* The Empire feature was published just in advance of the new cut’s screening at the 2012 Film4 FrightFest in London. This interview took place on June 12, 2012.

O: I have the impression that you tend to prefer not to talk about past projects and you’d rather look to the future? So thank you for this.

Clive Barker: This is a very different situation. So, Hellraiser was what Hellraiser was. It was a $900k movie, and there wasn’t anything I would have done differently. But Nightbreed was taken away from me. It was thought that its meaning wasn’t… Its meaning didn’t chime with the producers. The thought of making a movie in which the monsters were the good guys was just financial suicide. I had known all along that that was the movie that we were making, but there was a change of staff. Joe Roth, who bought the movie, was one of the partners at [studio] Morgan Creek when we started up the movie, but he left just before we started to shoot, because of some internal politics that I don’t know much about. He called me one night and said, ‘I will not be with you on this project; I’m sorry.’ And that was the end of that!

It made for a difficult transition, because the gentleman who then took over, Jim Robinson, had not read the script, was not aware that we were making a movie where the monsters were the good guys, and I don’t think he would ever have green-lit the movie. He would have thought it was a tough sell, put it that way. In one sense, I don’t actually think he’s wrong. There’s a part of the audience for horror movies that wants convention. The horror convention is that the monsters are the villains, and innocent people get punished, right? My thesis, if you will, is that monsters are a lot more interesting and complex than that, and our responses to them are a lot more interesting and complex. We go to monster movies to fall in love with them. We go to Dracula to see Dracula; we do not go to see Van Helsing. It’s not the guy who carries the holy water that touches our hearts; it’s the creature who bears the brand of evil and will be punished for it eventually, but actually has other things going on in its heart that the good guys won’t give credence to. That’s certainly true of Frankenstein’s monster; it’s true of Dracula; it’s true of the Werewolf. All these standard figures of monster movies have a moral ambiguity in common. We feel something much more complex than simple hatred for them… but they get punished anyway!

Is it a kind of anti-establishment thing – siding with the underdog?

It’s partly an anti-establishment thing, and I’ve personally never played by the rules. As a writer, I’m not really interested in telling a story that has been told many times before. That’s not to say that I don’t believe there can’t be great horror movies in which monsters are really terrifying things. Pazuzu is a really terrifying figure in The Exorcist, and I love that movie. But I also love the possibility of introducing audiences to things that redirect their attention to things they may not have considered. I wanted Nightbreed to be a movie that made people think twice about why they love monsters. Unfortunately, when Morgan Creek finally saw the movie that I’d actually made, they said, ‘No, definitely not. Monsters are never good.’ It was a response to my anti-establishment stance: I think you’re right.

Was the novel written with the idea that it would become a film?

No, I never do that.

I just wondered because it’s something Graham Greene used to do. He felt he couldn’t write a screenplay unless he’d thrashed it out in prose first. That’s what he did with The Third Man, for example.

But he was also a movie critic. I love watching movies, but my passion is books. I would not feel good about writing a novel if the final form of it was not the form that I was writing in. That would seem a dishonourable thing to do to the reader: it’s almost like saying, ‘I don’t trust the reader enough to enjoy this.’ I wouldn’t be motivated that way. I’ve never picked up a pen on a Monday morning and said, ‘Now I’m going to write a novel that will be a movie!’ The first line of the first page is, ‘Soon to be a major movie!’ No.

So what was the genesis of the book? It’s very different to the rest of your novels: much shorter and much faster.

Some stories want to be long and some want to be shorter. I’d had a lot of fun writing The Books of Blood: six volumes of novellas and short stories that had worked very well. I had a story in Cabal that did not want to be the length of Weaveworld: it wanted to be the length pretty much that it is. Actually, I’ve never admitted to this, ever, I don’t think, but all the quotes at the beginnings of the sections, are invented! That was great fun to do, and it was very fun when some critics actually quoted them, and started talking about the oeuvres of the authors in question. That was the sort of fun I was having with the form, but I don’t believe the story would have sustained a sort of Weaveworld length. It was a nice, short, crisp tale.

Was it a sort of reaction to Weaveworld? Did you feel the need to knock out something short and action-packed after that one?

It’s certainly true that I finish big books with a little bit of energy left that’s not enough for another big book, but I can’t just sit there! Weaveworld was a couple of years of work, whereas Cabal was eight months. I don’t think the style was compromised because of that. I certainly tried to polish the book in the same loving fashion I polish everything else, and I believed in it passionately.

A while ago I was at a Horror Writers Association dinner and I made a speech, and I asked how many people were Catholic, or believed in God, or were generally Christian in the room, and there was a very small number of hands raised. We were all professional writers, I think. I then asked how many of us had actually used holy water or crosses or any of that iconography of Christianity as a deus-ex-machina to finish off a narrative, and a huge number went up! And I said that I think that is one of the reasons that we are not respected as horror writers, because we don’t speak from the heart. Don’t bring on something as powerful as that, if you don’t believe what you’re saying.

In Cabal, even though it’s very fantastical and full of strangeness, I wanted to be able to defend the belief system and the metaphysics behind it. I do think that the monstrous and the strange is victimised and oppressed, and that we need to think in a fresh way about our response to monsters.

It strikes me that there’s something of Tod Browning’s Freaks in it: was that in your mind?

I think not, actually. I like Freaks, but it’s a very unpleasant movie. Novels play out differently in everybody’s heads: The Moby Dick that you have in your head is a different Moby Dick than the one I have in my head. I think that the monsters in Cabal as people imagine them off the page are probably less distressing than Tod Browning’s freaks. There’s something about those freaks that is, particularly towards the end with things like the chicken woman, just distressing to the heart and soul in a way that I don’t think the monsters in Cabal are. It’s all in the eye of the beholder, but I happen to find Freaks a powerfully distressing picture, because obviously a lot of them are real. The pinheads in particular I find troubling, because you have to assume that they did not know what they were doing. So I find it, in a way, interestingly distasteful. I don’t think that people who read Cabal are imagining any sort of real deformities that you might find in hospitals.

So you have the novel and you think it’ll make a good film: what was the process of getting it set up at Morgan Creek?

I knew Joe, and I told him the idea, and he actually loved the idea of the monsters being the good guys; that was the thing that sold him on it, which is very paradoxical because it’s also what killed the movie so dead for twenty years! I was allowed to go forward, and I said to the guys at [FX house] Image Animation, who’d done Hellraiser, ‘This is my monster movie. Let’s enjoy it. Let’s celebrate making monsters, and let’s have fun.’ I don’t know if you ever saw a book called The Nightbreed Chronicles. That, I think, was an expression of the kind of fun we were having: this catalogue of strange and wonderful beings, males and females, some of them sexy, none of them like anything you’d seen before, except possibly in the cantina scene in Star Wars.

We got all that together and they all looked great, and we started shooting. It was not going to be an easy shoot because we had a lot to do in a short time. And then Joe was gone and Jim Robinson came over to see what was going on and told me the bad news. So even while I was shooting I realised I was up against a tough sell. But I liked Jim a lot; I’ve always liked Jim. I call him Uncle Jim, and even though we were at loggerheads over this movie for a long time, I’ve always found Uncle Jim a pleasant and funny guy. We’ve never had harsh words. We’ve yelled at each other, but it wasn’t harsh yelling! I think he respected the fact that I had a different philosophy to him.

How did you work with Image Animation? Did you design the creatures together, or were they coming to you with designs, saying ‘Look what we’ve done now!’

We worked together, and I would draw things and they would draw things: we would have mammoth drawing sessions where we were coming up with ideas in every direction. We were all just passionately in love with creating a very different kind of movie: one in which you went in to celebrate strangeness. There are certainly movies that had done that before. You rightly mentioned Tod Browning, and I actually think that James Whale did the same thing. I produced Gods and Monsters, and when you read about Whale, he was in love with the strange. With The Bride of Frankenstein, it’s very obvious when you look at the designs of, say, Dr Pretorius’ laboratory, with the little bottles with the people in them, this was a man who loved the strange.

So it wasn’t that Nightbreed was the first ever such movie. Arguably Disney movies are in love very often most with the strange. Maleficent is who we take away from Sleeping Beauty. It’s her magnificent transformation into a dragon that we remember; I can’t even remember the prince’s name! So I think right across the board, whatever type of movie, where there’s fantasy, where there’s horror, there’s some attraction towards the strange.

In a way it seems to me that Nightbreed is a fleshing out of the book. Often there’ll be a film and someone will then write a novelisation to expand on what’s on the screen, but Nightbreed weirdly seems the other way round.

I think that’s right. In a bizarre way, now that we have the movie the way that I think it should be, I can now fall in love with the film all over again. It is more fat on the bones of the text; it does show us what the text only implies.

Why did you cast David Cronenberg?

He’s cold, man! He’s not an actor, no, but what I liked was that there was a weirdness to him. An actor would have played a villain, whereas David didn’t. David played David. When he’s talking, he’s so plausible, especially in comparison to Charlie Haid who’s ranting and raving. It was wonderful to have those two very different personalities working together. I’m a big admirer of David’s, and I asked if he’d do it, and to my astonishment he said yes. When he wasn’t working he’d just sit around and write his William Burroughs script. He was great fun to have around.

The contemporary magazine articles are all you saying that the film has been taken away from you: it’s almost like you’re warning people away from the film.

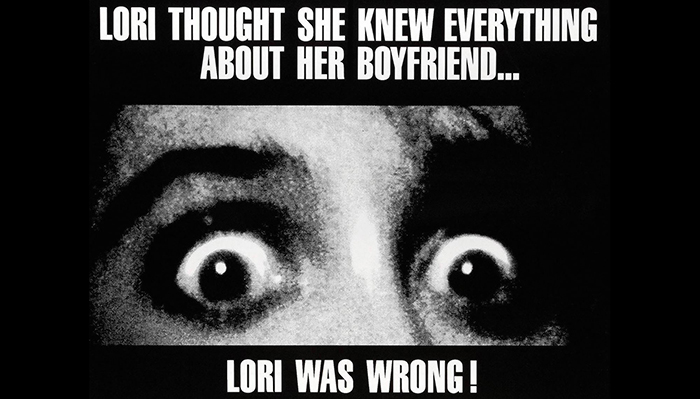

Absolutely. I wanted to be honest about it. I think not to have been would have been a double hypocrisy. I hated the poster. I hated so much that horrible slogan: “Lori thought she knew everything about her boyfriend… Lori was wrong!” It was totally the antithesis of what the movie was. It was a slasher poster. People went along expecting a slasher movie, and they didn’t get that. And people who were wanting a Clive Barker movie didn’t get that either! Nobody was happy, and the critics, of course, tore me limb from limb. I’d made Hellraiser and they’d loved me, and now, in time-honoured fashion, they hated me. Until Mark and Russell came along I had kind of given up hope that this movie would ever find its true form. I knew the material was there, and I knew we could cut it together correctly if we had the will and the money. And they have made this possible.

I’ve been following this story since 1990, and in the years since I’ve occasionally read interviews where someone’s asked you about a director’s cut, and you’ve always sort of said that it would be nice if somebody did it, as if you weren’t actually very inclined or energised yourself. Is that fair?

Well, the fact is that I didn’t know what material there still was, and I also felt that it was very painful. It was a lot of work that had demanded a lot of energy and a lot of fighting. I went out to lunch with Cronenberg during all the bad stuff, and he said something very funny. He said that the thing is, when we finish making a film we’re exhausted, and the producer is Daddy, and all you want is to take the film to Daddy, and you want Daddy to love it. You want Daddy to say, ‘Good boy!’ and get the marketing department going and take it out to the world. But the trouble is, you’re so vulnerable at that point, that if you don’t get that response – I didn’t – you just go down into a deep, deep hole.

I actually had that lunch with Cronenberg and John Landis, and both of them have had these experiences more than once. Later I had lunch with Tim Burton and he told me the same thing happened to him on Beetlejuice. There are lots of examples of where people have tried to take their movie to Daddy, and Daddy has said, ‘Get the fuck out of here!’ But with Beetlejuice, Tim had managed to fight off the destruction and succeeded. I had not succeeded. I had failed. The movie had come out the wrong way, and I felt that I’d failed my actors. The studio wouldn’t even pay for the real actors to dub it. I had to put up with dubs from people I didn’t know. They wouldn’t pay for Doug Bradley to come over to LA to do his voice, or to take me to London. I felt terrible about that. This was Doug; I’d known him since I was 15! I hated it. So you begin to see why I felt so bad about it. I felt I’d let everybody down, including myself. There were a lot of people who’d really given their love and pushed harder than they needed to on my behalf, and we had nothing to show for it. It broke my heart.

Before all the trouble, had it been coming together as you’d wanted it to? Was it the film you’d had in your head?

I think so, yes. The fact that we’re now able to reassemble the pieces in the right order testifies to the fact that it was all shot. So yeah, I was very optimistic. Richard Marsden, the original editor, had done an amazing job on Hellraiser, and had come over from London to do Nightbreed, but he got sick. In a very gentlemanly way he said, ‘I’m sorry, Clive, but I can’t be here. I’m either the editor of the movie or I’m not,’ and he withdrew and went back to London. So there was a real sense that I was losing my team and wasn’t gaining much in terms of the movie I really wanted, even though I had the storyboards and I’d fucking shot each shot! Mark Goldblatt, who I love and is a great guy, came in, but he had an impossible job.

Now we’ve been putting [The Cabal Cut] together and it is there. But you know what happens: when a movie gets finished, the pieces go in all directions, and what I was left with was a movie which went on to video in a form I despised. Fox initially said, ‘We didn’t even release that movie; that’s not ours!’ but later they realised that it was theirs after all, but they didn’t know where any of the footage was. So if in those old interviews – and I’m sure you’re quite right – I came across as distancing myself from it, it was because I couldn’t see a moment… I had gone into the thing with so much passion and so much love, so much thirst to deliver my message, and then to find that the movie as released kind of delivered the reverse of that message… It made me want to puke.

Can you tell me a bit about the musical number?!

I had a bootleg of KD Lang singing a wonderful song called Johnny Get Angry, and I gave that song to Lori. One of the reasons I hired Anne Bobby was because she has an unbelievable voice: literally a Broadway voice. The message of that song is “Get angry! Respond! Fight back!” and that was, of course, a lovely theme for the monsters. She was going to sing this song. We shot it. Boone watches her sing this song in a club, and then leaves forever, to go to Midian. And then she finds that he’s gone and never expects to see him again. The song became a leitmotif for her, and it allowed me to say something about her that I couldn’t say on the page, about this incredible passionate side to her. Anne performed the scene straight into the mic, on the day, and it was very moving to watch her singing this song on the stage, and there in the shadows is Boone, with tears in his eyes. It was an emotional centre, but it didn’t make all the sense in the world in Morgan Creek’s vision, so they wanted it taken out.

Watching a scene like that, along with all the others, get taken out and thrown away, was like a death of a thousand cuts, although Mark Goldblatt, bless his heart, did everything he possibly could to make me feel good about what was happening. He had cut many movies that I admired a great deal, so I had that. But I hadn’t accounted for Mark’s cutting style. Mark cuts things very fast; he cuts things to within an inch of their lives. Dickie called it ‘frame fucking!’ The studio were keen on that very fast style of cutting. They wanted an action picture, but I hadn’t made an action picture! I didn’t want to make an action picture! So you had this problem because it wasn’t shot that way. We had all these beautiful long shots, where we had the camera fly through things so beautifully… That rhythm… Mark would take a shot like that and cut it in half, and leave half in the picture. My feeling was either keep those shots whole or not at all. Everything jumps around in the ultimate theatrical cut. It has no true rhythm. If rhythm is about dancing, this wasn’t it: it was convulsing. And it hurt to watch because I knew that if you put the other halves back in, you had these graceful, beautiful moves.

I also knew that those moves would work with Danny Elfman’s wonderful choral score. I don’t know if you’ve ever played any of Danny’s music separately from their films, but it is wonderful to listen to. He’s a brilliant scorer and Nightbreed is one of his greatest works. He thought so too, by the way. Just as a funny comic aside, the movie was R-rated, and he had a boys choir, and none of them were allowed to see the film because they were all too young. So they all had to stand with their backs to the screen while they were singing. Can you imagine? Boys will be boys: there was no fucking way they were going to stand with their backs to the screen while there was all this horror going on! Tra-la-la-la… That’s one of the things that still makes me smile about the whole thing, is Danny’s contribution. One of the things that was positively reviewed across the board was Danny’s score. It was a vision of truly loving monster music! But brilliant though it was, it wasn’t enough. Everybody that worked on this movie poured their hearts and souls into it: nobody was on it for profit. All the beautiful model work… A lot of hearts were broken: not just mine.

And now?

So much of this was celebrating monsters and their makers. I had in my head right from the beginning that we would have some stop-motion somewhere in the picture. I wanted the song – it’s back; I wanted the Harryhausen creature – it’s back. Slowly the movie started to resemble something that I’d dreamed of for years. It’s dark, but it’s about forgiveness and redemption. We’ve never had that before!

Very many thanks to Clive. I grew up reading your books and watching your films. This was a privilege.

*Nightbreed: The Director’s Cut will be released on Blu-ray by Scream Factory on October 28, 2014.