PHYSIOLOGY | IMAGES | ETYMOLOGY | TAXONOMY | GEOGRAPHY | BEHAVIOR | DIET | REPRODUCTION | ECOLOGY | CONSERVATION | FAUNAFACTS | VIDEO | SOURCES

The Livingstone’s flying fox is an Old World fruit bat, or megabat, and is one of the largest and most endangered of the bat species. Endemic to only two islands of the Comoros island chain, just off the coast of Africa, this herbivorous frugivore resides in forests and is threatened by habitat loss and human influences.

Physiology

The Livingstone’s flying fox is a megabat, so called for their larger weight and size than other bats. Like other megabats, the Livingstone’s flying fox’s tail is effectively absent.

The bat is referred to as a flying fox because of it’s canine-like muzzle and soft, thick, and often reddish fur.

The Livingstone’s flying fox, specifically, has three features that distinguishes it from other pteropodids, its black fur, rounded ears, and large, red-orange eyes.

It has a mostly black pelage with golden or tawny tinges on the rump, sides of the belly, and at times on each shoulder. The amount of golden hair varies between individuals with some having a narrow band of golden fur down the back with others being pure black without any paler hair at all.

The bat’s wings, legs, nose, and large, rounded, unique, semicircular ears are black and hairless.

The Livingstone’s flying fox has two upper and lower canine teeth. The first upper and lower molars are present. The bat’s cheek-teeth are simplified, with a reduction in the cusps and ridges resulting in a more flattened crown. Livingstone’s flying foxes are diphyodont, meaning that the young have a set of deciduous teeth, or milk teeth, that falls out and is replaced by permanent teeth.

The Livingstone’s flying fox uses its long, webbed fingers to fly.

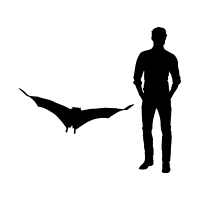

These bats weigh from 500 to 800 grams (18-28 ounces) and are about 30 centimeters (12 inches) in body length. Their wings have a wingspan of up to 1.5 meters (4 feet, 7 inches), an aspect ratio of 6.52, and a wing loading of 25.8 N/m2, and have been estimated to have a turning circle of 11.3 meters (37 feet).

The bats do not exhibit sexual dimorphism.

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

NoneBODY LENGTH

30 cm. / 12 in.WINGSPAN

1.5 m. / 4.9 ft.WING LOADING

25.8 N/m2TURNING CIRCLE

11.3 m. / 37 ft.BODY MASS

500-800 g. / 18-28 oz.LIFESPAN

10-30 yr.GENERATION LENGTH

8.1 yr.LOCOMOTION

Plantigrade

Images

Taxonomy

The Livingstone’s flying fox was described by Gray in 1866.

In 1912, Andersen gave the livingstone’s flying fox the scientific name Pteropus livingstonei. Although this should be the grammatically correct spelling, T. Huston from the Chrioptera Red List Authority and others note that the correct spelling should be livingstonii. Andersen’s 1912 emendation name is now considered unjustified and the Livingstone’s flying fox is referred to as Pteropus livingstonii.

The Livingstone’s flying fox is an Old World fruit bat, or megabat, in the genus Pteropus. Megabats constitute the family Pteropodidae of the order Chiroptera, containing bats.

Flying foxes are found in both genera, Acerodon and Pteropus.

No subspecies of the Livingstone’s flying fox have been recognized.

KINGDOM

AnimaliaPHYLUM

ChordataCLASS

MammaliaORDER

ChriopteraFAMILY

PteropodidaeGENUS

PteropusSPECIES

livingstoniiSUBSPECIES

None

Etymology

The Livingstone’s flying fox is also known as the Comoro black flying fox and the Livingstone’s fruit bat.

It’s scientific name is Pteropus livingstonii, though Pteropus livingstonei was used on the 2000 Red List. CITES also uses Pteropus livingstonei. There is debate over whether livingstonei or livingstonii should be the grammatically correct spelling. Andersen’s 1912 emendation of the species name is now considered unjustified.

The Livingstone’s flying fox is categorized in the Chiroptera order. Chiroptera is Greek for hand-wing.

The family Pteropodidae was first described in 1821 by British zoologist, John Edward Gray when he named the family Pteropidae and placed it within the now-defunct order, Fructivorae. However, Gray’s spelling was possibly based on a misunderstanding of the suffix of Pteropus, and was subsequently changed to Pteropididae. The Greek word pous of Pteropus derives from the stem word pod. As such, Latinizing Pteropus correctly results in the prefix Pteropod.

ALTERNATE

Comoro Black Flying Fox, Livingstone’s Fruit BatGROUP

Cauldron, Cloud, Colony, HaremFEMALE

DamYOUNG

Pup

Region

The Livingstone’s flying fox is endemic to the Union of the Comoros island chain, just off the coast of Africa, where it is only found on the islands of Anjouan, also called Nzwani, and Mohéli, also called Mwali.

The Extent of Occurrence, calculated as the minimum convex polygon around the area above the minimum observed altitude above sea level on each of the two islands, is estimated as 1,856 km². This includes unsuitable areas of land and ocean located between patches of suitable habitat.

The total land area of Anjouan and Mohéli is a combined 635 km². However, not all this area is occupied by the Livingstone’s flying fox. The species is found within a combined area on the two islands ranging from 99.1 km² (minimum convex polygons around all known currently occupied long-term roost sites: Anjouan = 90.2 km² Mohéli = 8.9 km²) to 462.5 km² (minimum convex polygons around all potential but unconfirmed foraging and roosting areas in native forest, degraded forest and agroforestry habitats above the lowest elevation of recent sightings on each island [450m-1050m asl on Anjouan, and above 200m asl on Moheli]: Anjouan = 326.9 km², Mohéli = 135.6 km²). These two figures represent the possible range of this species on the two islands it inhabits. This represents a substantial decline over the past five years.

A land cover classification conducted in 2012 using high-resolution satellite imagery and extensive ground-truthing found the combined area of native forest, forest with little trace of human impact and a closed canopy, on both islands was 54.7 km² (29.6 km² in Anjouan; 25.1 km² in Moheli). The combined area of native forest and degraded forest, forest either underplanted with crops, or with localized logging or clearance for fuelwood, on both islands was 143.1 km².

Within the smallest total range on both islands, the area around all known currently occupied long-term roost sites, the Area of Occupancy or surface area of potentially occupied habitat, such as native and degraded forest and agroforestry habitats that could be used for either roosting and foraging, is estimated to be 65.0 km² (Anjouan = 56.8 km², Moheli = 8.2 km²). Within the largest total range on both islands, the equivalent estimate for Area of Occupancy is 188.4 km² (Anojuan = 114.07 km², Moheli = 74.34 km²). Thus, the estimated total Area of Occupancy for this species is 65.0 – 188.4 km².

EXTANT

Comoros

Habitat

The Livingstone’s flying fox roosts and forages primarily in native forests and underplanted forests and avoids areas heavily affected by human disturbance.

They prefer to roost in emergent trees, primarily on steep-sided valleys with southeast facing slopes, near ridge tops and in areas generally associated with dense natural vegetation. Populations of this bat are largely confined to primary tropical moist forest, especially in montane areas.

Specifically, on Anjouan, all the major roosts are restricted to a narrow mid-altitudinal range (600-960 meter asl) and are strongly associated with the presence of native and endemic trees, with most of the largest roosts located in dense canopy, old growth forest.

Ficus esperata, Girostpula comoriensis, Gambeya spp., Ficus lutea, and Nuxia pseudodentata are the five most commonly used tree species for roosting.

FOREST

Subtropical/Tropical Moist Lowland, Subtropical/Tropical Moist Montane

Co-Habitants

Seychelles Flying Fox

Behavior

Livingstone’s flying foxes form small groups, called harems or colonies, in which they roost and forage. Colony size typically ranges from 15 to 150 individuals. The largest known roosts have sometimes reached about 250 individuals during the rainy season, but not all of these are mature individuals. In general, members of the genus Pteropus form maternity colonies where females and their young gather. Females forage at night and return to their young in the maternity roost to nurse them.

Like other pteropodids, Livingstone’s flying foxes are nocturnal. They are active in the evening and at night when foraging for fruit.

Unlike other nocturnal bats, Livingstone’s flying foxes are capable of soaring on air thermals. Because they have very slow wing beats and a relatively slow, flapping flight, Livingstone’s flying foxes often glide and circle in an attempt to gain height, rather than fly directly. They use updrafts of warm air to help extend their gliding distance. Their wings have a wingspan of up to 1.5 meters (4 feet, 7 inches), an aspect ratio of 6.52, and a wing loading of 25.8 N/m2, and have been estimated to have a turning circle of 11.3 meters (37 feet).

Livingstone’s flying foxes often use vocalizations to communicate and have good vision.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

Nocturnal

Diet

Livingstone’s flying foxes are frugivorous herbivores and feed primarily on fruit. They also feed on nectar and leaves, to a lesser degree. Feeding is principally on native species but also includes non-native kapok (Ceiba pentandra). Particularly important food sources are native giant-leaved fig trees (Ficus lutea) and Ficus antandronarum.

In the dry season, Livingstone’s flying foxes tend to be much more selective on what and where they feed, preferring fig trees, but in the rainy season when more food is available, they feed on a larger variety of fruits. A very important tree for the Livingstone’s flying fox and the Seychelles flying fox (Pteropus seychellensis) during the dry season is the giant-leaved fig tree (Ficus lutea). This tree is chosen over many other fig trees.

The Livingstone’s flying fox may have naturally taken advantage of elevational differences in tree fruiting phenology to compensate for seasonal variation in fruit availability. Thus, the loss of large areas of foraging habitat, including all the lower parts of its elevational range, could result in seasonally restricted food availability.

In general, Pteropus species use olfaction to find fruiting trees and determine if fruit is ripe enough to eat.

PREFERENCE

GeneralistSTYLE

Forager

Reproduction

Livingstone’s flying foxes are polygynous as males attempt to mate with as many females as they can. Females will, however, mate with more than one male throughout their lifetimes.

The breeding season is from January through June.

Females do not reproduce during the first few years of life in captivity. The minimum dam age at first reproduction has been 3.4 years, whereas the average dam age at first reproduction is 5.9 years, and the average age of females giving birth is elevated (of all dams born in captivity that have since died or are more than 10 years of age, mean age when giving birth = 8.1 years).

Like most mammals, chemoreception is important in communicating sexual receptiveness.

There is limited information available specifically on parental investment in the Livingstone’s flying fox, but males are known not to stay around after mating, leaving the females to raise and care for the young.

The young are weaned within 4 to 6 months of being born.

BREEDING SEASON

January-JunePARENTAL INVESTMENT

MaternalGESTATION

4-6 MonthsBIRTHING SEASON

July-OctoberLITTER

1WEANING

4-6 MonthsSEXUAL MATURITY

3.4-5.9 yr.

Ecology

Members of the genus Pteropus are important in the dispersal of seeds in the forests they inhabit. They are often seen as keystone species because they maintain forest regeneration patterns. As such, Livingstone’s flying foxes are important members of their native ecosystems, helping to disperse fruiting tree species and sometimes pollinate plants.

There are no adverse effects of Comoro black flying foxes on humans.

Other predators have not been documented, but large arboreal snakes and raptors make take young and adult Livingstone’s flying foxes.

Humans are the primary predators of the species, both for food and as a secondary result of forest destruction. The species is suspected to suffer from catastrophic habitat decline caused by the cutting of trees for fuelwood and construction and by conversion of all but the steepest upland areas to agricultural use. This has resulted in extensive declines in the species’ area of occupancy, the extent of its occurrence, and the quality of its habitat. Rapid destruction of the forest habitats the bat relies on indicates these flying foxes may become extinct within 10 years. Human pressures on native forests are expected to continue, as the growth rate of the human population remains high, with an annual increase of 2.5%.

There is no evidence that the Livingstone’s flying fox is hunted for food, a key factor affecting other fruit bat species. This may be due in part to cultural taboos among the majority of the population that surround consumption of fruit bats. However, the apparent lack of hunting may also be due in part to the bat’s habit of roosting in inaccessible areas remote from towns.

Some limited hunting of the other two fruit bat species in the Comoros has been occasionally recorded. It is unclear if the increased access to formerly inaccessible roost areas could expose the bats to any hunting pressure in the future, but any such hunting would likely first affect the flying fox’s congener, the Seychelles flying fox (Pteropus seychellensis comorensis), which sometimes roosts and forages in visible locations in or near towns.

Predators

Human

Conservation

The Livingstone’s flying fox is listed as Critically Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species because of a serious population decline.

The species is suspected to suffer from catastrophic habitat decline caused by the cutting of trees for fuelwood and construction and by conversion of all but the steepest upland areas to agricultural use for subsistence agriculture and for export crops such as cloves. This has resulted in extensive declines in the species’ area of occupancy, the extent of its occurrence, and the quality of its habitat.

Rapid destruction of the forest habitats the Livingstone’s flying fox rely on indicates these bats may become extinct within 10 years. Best estimates, derived from the little available data on forest loss rates, suggest that habitat decline over the most recent three generation, or 24.3-year period, was 83%. Thus, the best estimate of loss of this species’ habitat exceeds the threshold for Critically Endangered status (=80% loss of population, as suspected by habitat change, over a three-generation period, where habitat loss is ongoing).

Population

True changes in the population size of the Livingstone’s flying fox are currently unknown, and data on habitat change over time is limited but is likely to be linked to changes in forest and underplanted forest habitat. However, the species qualifies for the Critically Endangered status because best estimates indicate habitat loss has exceeded 80% over the past three generations (estimated generation length: 8.1 years/generation), because remaining habitat is increasingly degraded and fragmented, and because declines in the extent and quality of habitat are continuing. The geographic range is also small, such that the current extent of occurrence is estimated to be 1,856 km², less than the Endangered threshold of 5,000 km². In addition, the habitat is severely fragmented, and there have been clear, continuing, observed declines in extent of occurrence, area of occupancy, habitat quality, and number of locations. Declines in the number of mature individuals are also inferred from these declines in habitat.

Livingstone’s flying foxes are one of the most critically endangered bat species, with an estimated population size of 400-1,300 individuals. Repeated simultaneous surveys of all 23 known roosts during 1998-2006 typically recorded about 1,200 bats. Many of these roosts were located as a result of the implementation of a national monitoring program. Surveys have been conducted only sporadically since 2007, so it is unclear whether populations have changed recently. However, a survey conducted with sequential visits to all previously-known roosts in 2011 and 2012 estimated 1,300 bats across 22 roosts (Anjouan: 940 bats at 16 roosts, Mohéli: 360 bats at 6 roosts).

MATURE INDIVIDUALS

1,300FRAGMENTATION

Severely Fragmented

THREATS

Humans are the primary predators of the species, both for food and as a secondary result of forest destruction. Human pressures on native forests are expected to continue, as the growth rate of the human population remains high, with an annual increase of 2.5%.

The Livingstone’s flying fox is threatened principally by the continuing degradation, fragmentation, and loss of its forest habitat. Over the last few decades, the Comoros have undergone a sustained, rapid deforestation, resulting in the loss of nearly all its native forests. Data quality on rates of habitat loss is poor, but best estimates are that during the past 20 years alone, the country has lost 75% of its remaining forests, the fastest rate of any country in the world.

The mean surface temperature of the Comoros is thought to have increased about 1° Celsius since 1900 and is expected to increase by 1-3° Celsius more by 2100 due to global climate change. It is unclear whether or how such changes will affect the Livingstone’s flying fox, but since thermal characteristics are important components of roost suitability for this and other Pteropus species, predicted temperature increases could negatively affect the availability of suitable roosting habitat.

With continuing habitat change, the Livingstone’s flying fox has retreated to higher elevations. On the island of Anjouan, the Livingstone’s flying fox avoids all lower elevations with the lowest record of feeding at 300 meters asl. On Mohéli, some limited forest patches extend to near sea level and the lowest record of feeding is at 40 meters asl. Even above these elevations, forest habitat on both islands, and especially Anjouan, has undergone extensive and continuing habitat degradation, fragmentation, and loss, leaving large areas increasingly unsuitable for this species. Nearly all lower-elevation native forests have been lost, and in the past five years, there have been no records of this species below approximately 450 meters on Anjouan or below 200 meters on Mohéli. The total land area of Anjouan and Mohéli is a combined 635 km². However, not all this area is occupied by the Livingstone’s flying fox. The species is found within a combined area on the two islands ranging from 99.1 km² (minimum convex polygons around all known currently occupied long-term roost sites: Anjouan = 90.2 km² Mohéli = 8.9 km²) to 462.5 km² (minimum convex polygons around all potential but unconfirmed foraging and roosting areas in native forest, degraded forest and agroforestry habitats above the lowest elevation of recent sightings on each island [450m-1050m asl on Anjouan, and above 200m asl on Moheli]: Anjouan = 326.9 km², Mohéli = 135.6 km²). These two figures represent the possible range of this species on the two islands it inhabits. This represents a substantial decline over the past five years.

Roost sites represent critical habitat for the Livingstone’s flying fox, yet tree felling has destroyed a number of roosts, leading to displacement of bats to less impacted areas, often at higher elevations. Of 23 roosts occupied in 2007, three roosts have been abandoned due to clear felling of forest in the past five years, and only one new but very small roost of 15 bats has been uncovered despite extensive searching efforts. This new roost was found in a patch of degraded forest at 1050 meters, the first to be found at such a high elevation, and is believed to have been established very recently.

On Anjouan, forest clearance, underplanting or significant soil erosion following deforestation upslope of the roost was found within 50 meters of all but one of the 16 occupied roosts. Further, the replacement of native forests with agricultural lands on Anjouan and Mohéli may render formerly inaccessible roost sites on Anjouan and Mohéli more accessible, possibly exposing roosts to increased levels of human disturbance. Finally, the loss of native forests has resulted in impermanence or complete drying of nearly all rivers on Anjouan and many on Mohéli. As Livingstone’s flying fox roosts are often associated with rivers and other humid environments, a factor which may be related to their thermal sensitivity, this loss of rivers may additionally affect the quality of roosting habitat.

Lastly, the Livingstone’s flying fox’s small population is found within a restricted range solely on two small, adjacent islands. The species is therefore susceptible to single threatening processes, like cyclones, that could simultaneously or rapidly affect its entire range.

RESIDENTIAL & COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Housing & Urban AreasAGRICULTURE & AQUACULTURE

Annual & Perennial Non-Timber Crops, Wood & Pulp PlantationsBIOLOGICAL RESOURCE USE

Logging & Wood HarvestingHUMAN INTRUSIONS & DISTURBANCE

Work & Other ActivitiesCLIMATE CHANGE & SEVERE WEATEHR

Storms & Flooding

ACTIONS

A detailed conservation plan for the Livingstone’s flying fox, the Conservation Action Plan for Livingstone’s Flying Fox was developed by the non-governmental organizations Action Comores Anjouan and Action Comores International, and a consortium of other conservation groups, through a participatory process involving a broad range of stakeholders. This conservation plan was adopted by the government of the Union of the Comoros as the national conservation strategy for this species and has served as a guide for conservation action. The plan identifies a conservation strategy with several key elements, including habitat protection, forest management, environmental education, population monitoring, ecological research, ex-situ breeding, and conservation partnerships.

A long-term comprehensive citizen science program involving Comorian villagers in population monitoring for this species was led by Action Comores Anjouan and Action Comores International between 1992 and 2006.

Population surveys and habitat evaluation around roost sites was conducted by Engagement Communautaire pour le Développement Durable of the Bristol Zoological Society and Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust between 2009 and 2012, and by Dahari more recently.

A national environmental education program was implemented by Action Comores Anjouan and Action Comores International, and it was successful in raising local and international awareness of this species and the threats it faces, in improving training of local personnel, and in increasing local participation in conservation and science programs.

A small community-based ecotourism program for this species has been implemented on Mohéli by Projet Conservation de la Biodiversité et Développement Durable and is maintained by the local community in Ouallah 2.

Dahari is implementing integrated landscape management around the southern forest block of Anjouan. This involves sustainable land management at the roosting and foraging habitat of this species and a pilot program of payment for ecosystem services both within the Moya Forest area. Research by Dahari and partners into feeding ecology and the genetics of roost-site populations is also planned.

There is an active captive-breeding program underway for the Livingstone’s flying fox initiated by Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust in 1992. The program began with 17 founder individuals, 7 females and 10 males, captured from the wild on Anjouan during 1992-1995. The captive population of the bat subsequently expanded at a slower rate than other fruit bat species in captive breeding programs, such as the Rodrigues flying fox (Pteropus rodricensis), at least initially. However, by 2014, the Livingstone’s flying fox captive population had reached 59 individuals, 22 females and 37 males, housed at four institutions: the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust in Jersey, U.K.; Bristol, Clifton; West of England Zoological Society, in Bristol, U.K.; North of England Zoological Society in Chester, U.K.; and Lisieux Cerza in Lisieux, France.

The Livingstone’s flying fox receives the highest level of legal protection available within the Union of the Comoros. It is listed as an “integrally-protected species”, which prohibits the capture or detention of individuals without a permit. This law also expressly prohibits the killing of flying fox individuals; transport, purchase, sale, export or re-export of live or dead flying fox individuals or body parts; all disruption during the period of reproduction and raising of young; and the destruction of roosts.

The Union of the Comoros also ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1994, and in response has developed a National Biodiversity Conservation Strategy. This strategy highlights the importance of, threats to, and conservation recommendations for fruit bats of the Union of the Comoros.

The Livingstone’s flying fox is also listed on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, or CITES, which prevents international trade in specimens of this species without a permit. In practice, however, enforcement activities within the Comoros for these laws and treaties have been very limited in scope.

The Livingstone’s flying fox does not occur in any protected areas. However, critical roosting habitat at seven key roost sites that together harboured more than half the population was identified during the development of the Conservation Action Plan for Livingstone’s Flying Fox. Habitat conservation of these roost sites was identified as a key goal in this plan.

As part of its implementation, Action Comores Anjouan and the Comoros Forest Reserves Project conducted a conservation assessment to identify the two highest-priority sites, roost sites Yiméré on Anjouan and Hassera-Ndrengé on Mohéli, where the establishment of protected areas for roost habitat would be both highly beneficial to biodiversity conservation and highly feasible. These two groups also completed conservation planning for protection of critical roosting habitat at all seven of these critical roost sites.

Implementation efforts by Action Comores Anjouan and partners to conserve habitat around critical roosting habitat on Anjouan and Mohéli are under development. A project to establish larger reserves to protect rainforest and cloud forest on both Anjouan and Mohéli, which would include roosting and foraging habitat for this species, has been proposed by the United Nations Development Programme, the Global Environmental Facility, and the Comorian government.

The success of habitat conservation and restoration efforts will be particularly critical to the long-term prospects for this species.

FaunaFacts

Video

SourceS

- Clark, K. M., Carrol, J. B., Clark, M., Garrett, S. R. T., Pinkus, S., & Saw, R. (1997). Capture and survey of Livingstone’s fruit bats Pteropus livingstonii in the Comoros Islands: The 1995 expedition. Dodo, Journal of the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trusts, 33: 20-35.

- Daniel, B. M., Green, K. E., Salim, D, M., Saïd, I., Hudson, M., Doulton, H., Dawson, J. S., & Young, R. P. (2016, November). A bat on the brink? A range-wide survey of the endangered Livingstone’s fruit bat Pteropus livingstonii. Oryx, 1-10.

- Dechmann, D. K. N. & Safi, K. (2005, January). Studying communication in bats. Cognition, Brain, Behavior, 9(3), 479-496.

- Dewey, T. & Long, J. (2007). Pteropus livingstonii. Animal Diversity Web.

- Doulton, H., Misbahou, M., Shepherd, G., Mohamed, S., Ali, B., Maddison, N. (2015, September). Competing Land-Use in a Small Island Developing State: Using Landscape Approaches to Manage Sustainable Outcomes in the Comoro Islands. Durban, South Africa: XIV World Forestry Congress.

- Green, K. (2014, February). Land Cover Mapping of the Comoros Islands: Methods and Results. Engagement Communautaire pour le Développement Durable (ECDD), Bristol Conservation & Science Foundation (BCSF), & Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trusts.

- Emanoil, M., Edward, J., Kasinec, D. (1994). Comoro black flying fox. In M. Emanoil, J. Edward, D. Kasinec, P. Lewon, J. Longe, K. McGrath, Z. Minderovic, J. Muhr, N. Schlager, B. Tavers, S. Walencewicz, & R. Young, (Eds). Encyclopedia of Endangered Species (1 ed., Vol. 1) (pp. 62-63). Detroit, MI: Gale Research Inc.

- Fox, S., Luly, J., Mitchell, C., Maclean, J., & Westcott, D. A. (2008, January). Demographic indications of decline in the spectacled flying fox (Pteropus conspicillatus) on the Atherton Tablelands of northern Queensland. Wildlife Research, 35(5), 417-424.

- Gould, E., Woolf, N., & Turner, D. (1973, December 14). Double-note communication calls in bats: Occurrence in three families. Journal of Mammology, 54(4), 998–1001.

- Granek, E. F. (2002, November). Conservation of Pteropus livingstonii based on roost site habitat characteristics on Anjouan and Moheli, Comoros Islands. Biological Conservation, 108(1), 93-100.

- Hutchins, M., Kleiman, D., & Geist, V. (2003). Species account: Livingstone’s fruit bat. In M. Hutchins, D. Kleiman, V. Geist, M. McDade, (Eds). Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia (2 ed., Vol. 12-16) (pp. 327). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

- Malik, K. (2013). Human Development Report 2013: The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme Human Development Report Office (UNDP-HDRO).

- Mickleburgh, S. P., Hutson, A. M., & Racey, P. A. (1992). Old World Fruit-Bats – An Action Plan for their Conservation. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

- O’Brien, J. (2011). Bats of the Western Indian Ocean Islands. Animals, 1(3), 259-290.

- Pacifici, M., Santini, L., Di Marco, M., Baisero, D., Francucci, L., Grottolo Marasini, G., Visconti, P., & Rondinini, C. (2013, November). Generation length for mammals. Nature Conservation, 5(6025), 87–94.

- Pierson, E. D. & Rainey, W. E. (1992). The biology of flying foxes of the genus Pteropus: A review. In: D. E. Wilson & G. L. Graham (Eds.), Pacific Island Flying Foxes: Proceedings of an International Conservation Conference (pp. 176). Biological Report, 90(23). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Sewall, B. J. (2002). Fruit Bat Ecology and Conservation in the Comoros Islands (Masters Thesis). University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

- Sewall, B. J., Freestone, A. L., Moutui, M. F. E., Toilibou, N., Saïd, I., Toumani, S. M., Attoumane, D., & Iboura, C. M. (2011, August). Reorienting systematic conservation assessment for effective conservation planning. Conservation Biology, 25(4), 688-696.

- Sewall, B. J., Granek, E. F., Moutui, M. F. E., Trewhella, W. J., Reason, P. F., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M., Saïd, I. Carroll, J. B., Masefield, W., Toilibou, N., Vély, M., ben Mohadji, F., Feistner, A. T. C., & Wells, S. (2007). Conservation Action Plan for Livingstone’s Flying Fox: A Strategy for an Endangered Species, a Diverse Forest, and the Comorian People. Union of the Comoros: Action Comores Anjouan.

- Sewall, B. J., Young, R., Trewhella, W. J., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M. & Granek, E. F. (2016). Pteropus livingstonii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T18732A22081502.

- Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M. M. B., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., & Midgley, P. M. (Eds.) (2013). Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Tidemann, C. R. & Nelson, J. E. (2011, December). Life expectancy, causes of death and movements of the greyheaded flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) inferred from banding. Acta Chiropterologica, 13, 419-429.

- Trewhella, W. J., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M., Corp, N., Entwistle, A., Garrett, S. R. T., Granek, E., Lengel, K. L., Raboude, M. J., Reason, P. F., & Sewall, B. J. (2005, January 19). Environmental education as a component of multidisciplinary conservation programmes: Lessons from conservation initiatives for critically endangered fruit bats in the Western Indian Ocean. Conservation Biology, 19(1), 75-85.

- Trewhella, W. J., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M., Davies, J. G., Reason, P. F., & Wray, S. (2001, January). Sympatric fruit bat species (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) in the Comoro Islands (Western Indian Ocean): Diurnality, feeding interactions and their conservation implications. Acta Chiropterlogica, 3(2): 135-147.

- Wikipedia. (2018, December, 6). Livingstone’s fruit bat. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.