This month, I made it to the Sierras for two great hikes with my brother and sister-in-law. The first was in Sequoia National Park in the Southern Sierras and the second took us into the heart of the Desolation Wilderness west of Lake Tahoe in the Northern Sierras. While these hikes are further away from each other than either is from Santa Cruz, they share many of the same habitats and thus have generally similar floras. On both hikes we walked through montane and subalpine forests, which were broken up by meadows, wetlands, and talus (big rock) slopes. On both, we made it into the alpine zone. Alpine habitat is easy to distinguish–by definition it includes anything above the tree-line, which is usually around 10,000 feet in the Sierras. Montane and subalpine forests, however, both contain a mix of coniferous tree species and grade into each other somewhere between 7,000 and 8,000 feet. Montane forests are characterized by Ponderosa and Sugar Pines, White Fir, and Douglas-Fir. Our first hike started in a giant grove of Sequoias, which are a component of Montane forests unique to a few spots in the Southern Sierras. Moving up in elevation, the larger, faster-growing montane trees are replaced by their more hearty subalpine relatives such as White, Whitebark, and Foxtail Pines, Red Fir, and Mountain Hemlock. The Desolation Wilderness subalpine also had some impressive Mountain Juniper trees.

But you’re here for the flower pictures, so let’s get to those. For each species, I’ll give the habitat where it is the most common, as well as the hike location if it is not found throughout the Sierras. Mid-August is a bit past the peak wildflower season, even high in the mountains. Several families of plants with many representatives in the Sierras, such as Liliaceae (sensu latu), Ericaceae, and Ranunculaceae, were mostly or completely finished blooming. For instance:

Phyllodoce breweri (Purple Mountainheath, Ericaceae, subalpine)

This is a super common Sierra shrub, but only a couple patches on both hikes still had flowers.

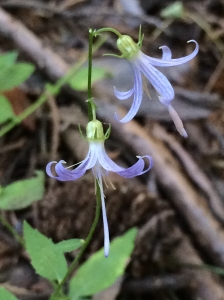

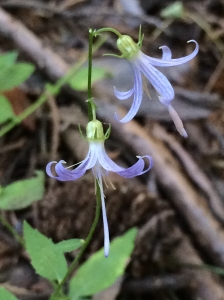

Flowering columbines were hard to find, so I made due with these shots of pretty much the last individuals in bloom:

Aquilegia formosa (Western Columbine, Ranunculaceae, subalpine)

Aquilegia pubescens (Sierra Columbine, Ranunculaceae, alpine, Sequoia)

The red flowered A. formosa is pollinated by hummingbirds and is found throughout Western North America. A. pubescens is pollinated by hawkmoths and is endemic to high elevations in the southern Sierras. The longer nectar spurs in A. pubescens ensure hawkmoths stick their tongue deep into the flowers, making contact with the reproductive parts. These species hybridize where they co-occur, producing a range of pinkish to orangeish flowers.

I also managed to scrounge up one flower of Anemone occidentalis (Western Pasque Flower, Ranunculaceae, alpine).

While the fuzzy flowers are cool, the Truffula Tree-looking fruits on this guy (right photo) are the main attraction. The fuzzy plume coming off each seed (actually a modified style) aids in wind dispersal, helping the plant colonize distant mountaintops.

Pedicularis attollens (Little Elephant’s Head Orobanchaceae, subalpine and alpine meadows) is another earlier bloomer that was still hanging on in a couple places.

The strange, asymmetric flowers ensure that visiting bees twist themselves into the correct position for maximum pollen movement.

While these and other species are busy ripening fruits, there were still plenty of others in full bloom.

In the montane forests of Sequoia, Asyneuma prenanthoides (California Harebell, Campanulaceae) and Leptosiphon montanus (Mustang Clover, Polemoniaceae) were putting on a show.

In the subalpine, I found Sphenosciadium capitellatum (Ranger’s Buttons, Apiaceae) along streams and Cirsium andersonii (Rose Thistle, Asteraceae) in open, grassy woods.

And among the rocks in the alpine, I stumbled on Epilobium obcordatum (Rockfringe, Onagraceae), and Dicentra nevadensis (Sierra Bleeding Heart, Papaveraceae, Sequoia)

The latter plant was quite common in places in Sequoia, but was the globally rarest plant I found. It’s pretty much restricted to Tulare county.

Another favorite from the hike was Parnassia palustris (Marsh Grass of Parnassus, Parnassiaceae, subalpine)

Although, not rare, I had never seen this species, or anything else in the small Parnassiaceae family before, probably because of it blooms later in the season than my previous Sierra hikes. Zoom in on the picture to check out the cool fan-shaped stamens.

For several plant genera, you can find multiple species by traveling from the montane to the alpine zones. Indian Paintbrushes (Castilleja) are a good example. My favorite from the hikes was the cream-colored Castilleja nana (Dwarf Alpine Paintbrush, Orobanchaceae, alpine)

But I saw at least two, and probably more, red and orange species.

Cinquefoils (Potentilla) are another diverse genus in the sierras. Potentilla grayi (Gray’s Cinquefoil, Rosaceae, subalpine, Desolation), was my favorite as it’s both the cutest and the globally rarest.

I didn’t take other pictures of Cinquefoils, because the flowers of the different species pretty much all look the same. However, the serrated, compound leaves come in a variety of shapes and sizes.

The most photographed genus of the trip was the Monkeyflowers (Mimulus). I pay particular attention to these guys as I’ve previously studied one. Plus I love the interesting combinations of spots and dots on the insides of the petals. Here are my three favorite species from the trip, but I saw 3 or 4 others:

Mimulus lewisii (Great Purple Monkeyflower, Phrymaceae, subalpine)

Mimulus primuloides (Primrose Monkeyflower, subalpine)

Mimulus whitneyi (Harlequin Monkeyflower, montane, Sequoia)

Yes, that’s four photos and only three species. The last two pictures are two color morphs of Mimulus whitneyi that were growing side by side.

I’ll end this month with what I think are the most iconic late-season flowers–the Gentians (Gentianaceae). These flowers are some of the last to bloom on many of the worlds mountains. They can keep their beautiful purple or white flowers open and seeds maturing through early fall frosts and snowstorms.

Gentiana calycosa (Explorer’s Gentian, subalpine)

Gentiana newberyi (Alpine Gentian, subalpine and alpine meadows)

Gentianopsis holopetala (Sierra Gentian, subalpine, Sequoia)

This is likely my last post for the year as those gentians signal the end of the flowering season in California. I’ll be back next year with more flowers from wherever I find myself.