Photo Courtesy of Kino International

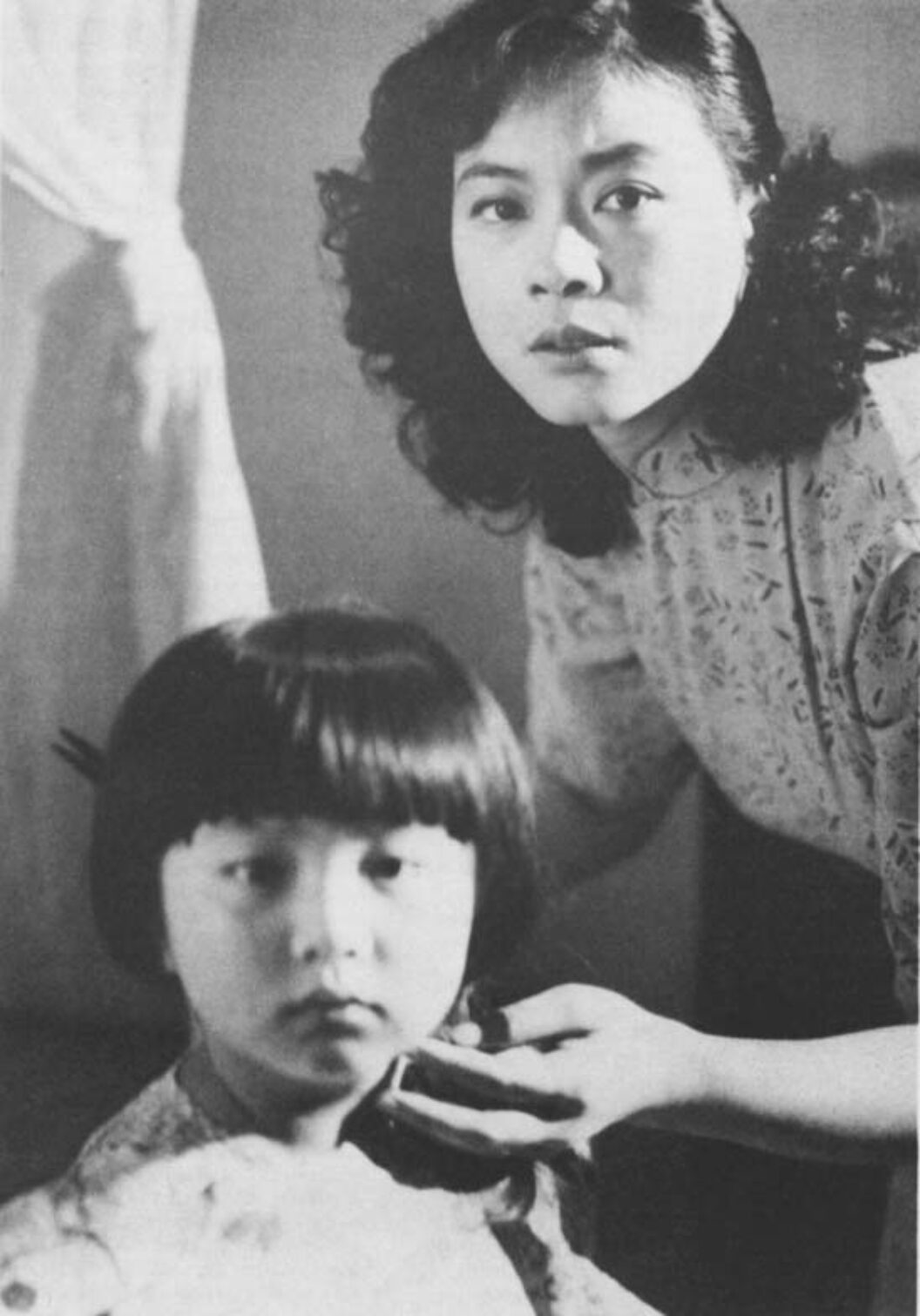

Unbelievably honest, Ann Hui is the most ruthless critic of her own work. She is best known for Boat People, her controversial 1983 film about the struggle for survival in Vietnam after its liberation from U. S. domination. One of the first Hong Kong produced films to be shot in the People’s Republic of China, it was initially banned in Taiwan, then taken out of distribution in Hong Kong, and, when the film’s complicated ideological structure surfaced, was forbidden to be shown in China as well. Her most recent film, My American Grandson, centers around the conflicts between a retired old man in Shanghai and his American grandson. Many see it as a continuation of her moving Song of the Exile (Kino International), the story of a young woman of mixed parentage who comes of age during the upheavals of the 1960s. Set in London, Hong Kong, China, and Japan, Song of the Exile follows her struggle with an identity constructed within the sharply defined ideas of race and sex in those cultures. Cunningly metaphoric, it is one of the most important features to be made by a Hong Kong director in the last half-decade.

Lawrence Chua In the taxi yesterday, you sounded unsure of the chances Song of the Exile would have in foreign festivals.

Ann Hui I just thought that it’s too much of a cross between things. It’s something between a commercial film and an art movie, something between a statement and personal, lyrical stuff—so it’s not quite anything.

LC Was that your intention?

AH It was not intentional. Nobody wants to start off making a hybrid product. It just happened.

LC You sound dissatisfied with it.

AH We pulled off a story which works, but I’m not very satisfied with my own ability. All of us tried our best. It’s a good effort, but if that’s the most I can do, I’m disappointed with myself.

LC Where did the original story come from?

AH The scriptwriter and I discussed it and gradually got the story out. It’s about the character’s realization of something during the course of the film, but at the same time, it’s about how people have drifted in our generation. I don’t know which message got across. I’m not running it down, but because of my own experience in commercial movies, the way it’s shot falls short of being more inventive. There should be a whole way of looking at the picture so that it’s more inventive in terms of sequences. Lots of things are very standard, although the structure isn’t.

LC Can you give me an example?

AH I’m really sincere in making this effort. I try my best to do it. I can’t think of a style or an aesthetic which is very good. When I first showed Song of the Exile, people thought it was very strange. They thought it should be a very quiet, ponderous film, but for the first two reels it has a very breakneck pace. Should an art film be like this? I’m just thinking about what sort of films I should be making in the future. People always criticize me for running myself down in front of interviewers, but I feel it’s better to find out what’s wrong with a film and improve it than to say what’s so good about it. I know what’s good about it. People say I’m trying to get a backhanded compliment, but that’s not my intention. At this stage, I don’t need compliments.

LC I know what you mean. It just looks funny to see these self-criticisms in print.

AH Don’t write it then.

LC What are your plans after this film?

AH I ought to go back to the mainstream of Hong Kong movie-making. The last two films I’ve been working on with my own company. It’s very hard work and involves a lot of coordination other than shooting. I’m not sure that if I go back to a commercial company and work as a director I’d be able to fit into the system, but I think I ought to try so that I can make films more quickly. Right now, there’s a restlessness. I don’t feel like making very thoughtful movies at present. If I keep on making independent movies of this kind, I’ll have to extend my scope into distribution and publicity. That will take years. Even financially, I can’t afford that time. I spent a whole year on Song of the Exile and I’m not working on preparing anything else for the next year. If I do that, I will have to make a big hit and have a share of the distribution profits, then I will be working on too few films. By the time I finish a film with the distribution, I won’t be able to catch up with the production and what’s going on with the film business. I’m not good enough to be able to make a film in two years and be able to learn a lot on the film, profit financially, and make enough of an impact to demand more money for the next movie. So I have to drop this method for the time being and try to make maybe three films in two years, to speed up the production and make the most out of the available material. I can see that if I go on making movies this way and they’re not smash hits, I’ll be finished. It’s too much of a burden to feel that every film has to be a success. I better go back to working commercially. I know what the odds are there also. I will have to be very passive and wait for people’s approval on everything. Most of the better companies have very tight control over all aspects of production, including the creative ones.

LC Even three films in two years is slow by Hong Kong standards.

AH Yes, but with that amount of time, I can do a good film.

LC What happened to you after Boat People? I understand the Society of Freedom [the anti-Communist organization that every film worker in Hong Kong must join] made a lot of problems and that the film was banned in Taiwan and then in China.

AH I don’t feel very much affected by it. Even before Boat People, I got offers to make movies from companies that import films to Taiwan. The companies said they could fix the import regulations. In any case, I could only make one film a year, so it didn’t matter. I’m not losing many offers. Anyway, it just sorted itself out after Boat People. When the film was supposed to be distributed in Taiwan, I wrote a letter to the Society of Freedom. The producer of Boat People said I could write anything, that I hadn’t gone to China for any political reasons, purely for the location. But the Society of Freedom weren’t satisfied. They said I must write another letter saying that I deliberately went to China to make an anti-Communist film. I said I can’t do that. It would implicate too many people and get them into trouble. It wasn’t my intention anyway. The matter dropped and this film wasn’t distributed in Taiwan. After two years, things got better. I went back to China to shoot another movie. I wasn’t blacklisted by China, as far as I know. I went to shoot The Book and the Sword, and when I came back everything was different. Even the Taiwanese relaxed their restrictions and people were going back to China before June 4 and shooting movies. Now things are a little cooled off because of international embargoes against China: the subtle ones, not the obvious ones. The authorities in Taiwan initially said, “You can use any money except for Chinese money for investments, and any member of the cast except for the leading characters can be Chinese.” Then they changed it. Maybe it wasn’t clearly written or something, but when the film was finished, they banned it in Taiwan because of two or three minor characters were played by Chinese actors instead of Taiwanese ones. Then everybody stopped going to China.

Photo Courtesy of Kino International.

LC Did you begin shooting Song of the Exile before or after June 4, 1989?

AH After.

LC And the writing?

AH Before.

LC What kind of impact did the events of June 4, 1989 in China have on production?

AH None, really. It all went according to plan because we couldn’t change the script in the middle. We delayed shooting for maybe one month. We thought it would be too dangerous to shoot. The arrangement with Pearl River Studios [in Guangzhou] was very smooth, but we only shot for three days.

LC Most of the footage you shot was in Japan.

AH That was the main part of the movie. It’s about the reconciliation process between the mother and the daughter. The end [in Guangzhou and Hong Kong] is just to tie up the beginning. Actually it ran a little bit longer than I expected, maybe three minutes or four, almost a whole reel. But tell me, what do you think of Hong Kong movies? From your understanding of the production system, what kind of improvements can be made here?

LC Well, people seem a little eager to go back to making movies with big studios, but I don’t know if it’s really my place to say what improvements could be made.

AH Maybe if you’re not involved with it, you can see certain things more clearly. If you’re not bogged down by production details, ways of doing things that we’re used to, maybe you can see things better.

LC Do you think the production system here works?

AH It works for making movies very quickly. It doesn’t work for making very good movies.

LC I don’t know if that mediocrity is a result of the way the films are made. Maybe it has to do with Hong Kong’s history as a British colony and its insular existence. To a certain extent, it’s always been divorced from what’s going on in China. Someone growing up here hasn’t been affected as strongly by the political forces that you see in China or Taiwan. Their way of seeing is different, more insular. Even with the events of June 4, the sudden burst of political interest here seems more motivated by greed. Song of the Exile takes a rather optimistic view of the reconciliation, especially compared with some of your contemporaries. For instance, in one of the last scenes, Hueyin’s grandfather says from his deathbed, “China still has hope.”

AH That’s wishful thinking. You end up with a very bad situation and the only decent response is to react positively on a humanistic level. That’s not really accurate, but right now I haven’t got anything better to say. I’m not deliberately trying to lie, but that’s the best attitude you can put forward at this stage. But, as you said, maybe the whole situation facing this particular historical dilemma has really made people more aware. After a few years of political education in the flesh, people will have a way of reacting to these situations better and will be able to make better movies. After June 4, the immediate task is to really examine your values, all sorts of things are more essential than the aesthetics of a movie. You should ask to whom you owe your loyalties, apart from yourself. As a Chinese, you should be very happy about the end of the Unequal Treaties and the return to the motherland, but you have to ask yourself why you’re not reacting in the obvious, logical way. There are things other than your personal desires involved. But I haven’t come up with any answers. I feel the best thing to do in the next few years is to analyze the situation better. Rather than make personal and wishful obvious films about what I feel about the situation, to concentrate more on what the situation is. Filmmakers usually use their eyes to tell a story very subjectively, mixing in a lot of what they think the situation is and how they react to it, but maybe I should set up the problems in this particular situation clearly and show the dilemma rather than adding my solution and qualifying that objective thing with many personal intrusions.

LC Is that something you’ve tried to do with Song of the Exile?

AH No, in Song of the Exile, I pushed everything towards the reconciliation. If I was making that movie now, I would have showed the whole situation as much less solvable—really just try to show the problem.

LC Do you think it is unsolvable?

AH Well, not really, but all that good will and understanding should come in a more difficult sort of way.

LC Why do you think there is no one working in Hong Kong on par with the “Fifth Generation” directors in the mainland or the “new wave” directors on Taiwan?

AH As you said, it’s the insularity of Hong Kong, the way people don’t look beyond a certain horizon, so the films don’t have a certain significance. The subject matter is limited and the way you look at a subject is only on a particular level. I don’t see how that problem can be remedied. We grow up with certain things. It’s too difficult to suddenly make a breakthrough. Maybe after a few years, if people are still allowed to make films, there will be some improvements.

Photo Courtesy of Kino International.