For over 60 years, Formula 1 teams have developed, tested, and built the fastest and most technologically impressive cars the world has ever seen. An almost unending list of superlatives can be ladled onto F1 cars: they can accelerate from 0 to 190mph in about 10 seconds, fling around a corner at such speeds that the driver experiences g-force close to that of an Apollo astronaut during Earth re-entry, and then decelerate by 60mph in just 0.7 seconds thanks to strong brakes and massive downforce—the same downforce that stopped the car from spinning out around that corner.

But the bit that's really impressive is that these machines are designed and built from scratch every year. That's what makes F1 so competitive and why the rate of improvement is so rapid. These teams—there are only about 10 of them, and most are based in England—have been challenging each other to make a new best-car-in-the-world every year for 60 years. The only way to pole position is to try to find an edge that no one else has thought of yet and then to keep finding new edges when everyone inevitably catches up.

As you've probably guessed, materials science, engineering, bleeding-edge software, and recently the cloud are a major part of F1 innovation—and indeed, those fair topics are where we lay our scene.

For this story I embedded with Renault Sport Formula One Team as they made their final preparations for the 2017 season. As I write this, I can hear this year's cars being tested around Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya; a Mercedes car has just set the fastest lap time, and we're all silently wondering if they will dominate once again.

After a difficult 2016, things are looking up for Renault Sport Formula One Team in 2017. They're back with a new chassis and a new, fully integrated Renault power unit. The engineering teams have been reinforced with new recruits and the acquisition of state-of-the-art tooling and machines. Planning, design, and international collaboration and communications have been bolstered with a renewed partnership with Microsoft Cloud. And F1 legend Alain Prost is on board to advise drivers Nico Hülkenberg and Jolyon Palmer.

How will they fare? I don't know; I'm a tech journalist, not a motorsports correspondent. But I can tell you how they built that car—or more accurately, how they built and scrapped thousands of possible, prototype cars in their search for one championship-winning design.

-

Various Ferrari Formula 1 cars, dating from 1950 to 2002.FlickrLickr

-

The Brabham BT46 "fan car."

-

A lot of changes were made to F1 cars following Senna's death, including the mandatory wooden plank (skid block) which shows if a car is running too low to the ground (and thus breaking regulations).

The discovery of downforce

For the first thirty years of Formula 1's history, the cars were mostly dumb mechanical beasts; not much mattered beyond the driver, tyres, and power train. Then, in 1977, Team Lotus (quite different from the recent Lotus F1 team, which then became Renault Sport Formula One Team) started paying more attention to aerodynamics—specifically the ground effect, which, in the world of motorsport, is usually known as downforce. The underside of the Lotus 79 F1 car was curved like an upside-down airplane wing, creating a pocket of low pressure that essentially sucked the car to the ground.

The Lotus 79 was massively successful, and before long—once the other teams eventually sussed out Lotus' black magic—every Formula 1 car was sculpted to provide maximum downforce. One design, the Brabham BT46 (pictured above), even had a big ol' fan that sucked air out from beneath the car.

Over the next few years Formula 1 got faster and faster, especially around corners. Eventually, following a number of accidents and the death of Gilles Villeneuve in 1982, the FIA mandated a return to flat-bottomed cars. The aerodynamic cat couldn't be put back in the bag, though.

-

An arty shot of a Formula 1 wind tunnel.Renault Sport Formula One Team

-

A 60-percent scale model of an F1 car inside the wind tunnel.Renault Sport Formula One Team

-

Formula 1 teams also have highly detailed car simulators to augment the limited amount of live track testing.Renault Sport Formula One Team

-

The car simulator control room.Renault Sport Formula One Team

-

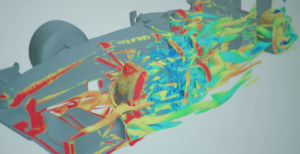

An F1 car within a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation.

-

A CFD aerodynamics engineer.Renault Sport Formula One Team

-

The supercomputer that runs the F1 team's CFD simulations. The team has a collaboration with Boeing, thus the Boeing label.Renault Sport Formula One Team

-

Another nice shot of the CFD supercomputer.Renault Sport Formula One Team

25 teraflops and not a drop more

Almost every area of technological and engineering advancement in F1 has followed a similar path to aerodynamics. A team finds an area that hasn't yet been regulated by the FIA, or where existing regulation can be creatively interpreted; that team pushes to within a few millimetres of the regulations, sometimes stepping slightly over the line; other teams follow suit; then the FIA revises its regulations and the cycle begins again.

As you can imagine, then, after some 60 years of trying to outwit the feds, Formula 1 today is governed by a rather long list of regulations—hundreds of pages of them, in fact.

For example, each Formula 1 team is only allowed to use 25 teraflops (trillions of floating point operations per second) of double precision (64-bit) computing power for simulating car aerodynamics. 25 teraflops isn't a lot of processing power, in the grand scheme of supercomputers: it's about comparable to 25 of the original Nvidia Titan graphics cards (the new Pascal-based cards are no good at double-precision maths).

Oddly, the F1 regulations also stipulate that only CPUs can be used, not GPUs, and that teams must explicitly prove whether they're using AVX instructions or not. Without AVX, the FIA rates a single Sandy Bridge or Ivy Bridge CPU core at 4 flops; with AVX, each core is rated at 8 flops. Every team has to submit the exact specifications of their compute cluster to the FIA at the start of the season, and then a logfile after every eight weeks of ongoing testing.

Renault Sport Formula One Team recently deployed a new on-premises compute cluster with 18,000 cores—so, probably about 2,000 Intel Xeon CPUs. While the total number of teraflops is strictly limited, other aspects of the system's architecture can be optimised. For example, the team's cluster has highly parallel storage. "Each compute node has a dedicated connection to storage so that we don't waste flops on reading and writing data," says Mark Everest, one of the team's infrastructure managers. "There was a big improvement in performance when we changed from our old cluster to the new one, without necessarily changing the software," and with the same 25-teraflops processing cap, Everest adds.

Everest says that every team has its own on-premises hardware setup and that no one has yet moved to the cloud. There's no technical reason why the cloud can't be used for car aerodynamics simulations—and F1 teams are investigating such a possibility—but the aforementioned stringent CPU stipulations currently make it impossible. The result is that most F1 teams use a somewhat hybridised setup, with a local Linux cluster outputting aerodynamics data that informs the manufacturing of physical components, the details of which are kept in the cloud.

Wind tunnel usage is similarly restricted: F1 teams are only allowed 25 hours of "wind on" time per week to test new chassis designs. 10 years ago, in 2007, it was very different, says Everest: "There was no restriction on teraflops, no restriction on wind tunnel hours," continues Everest. "We had three shifts running the wind tunnel 24/7. It got to the point where a lot of teams were talking about building a second wind tunnel; Williams built a second tunnel.

"We decided to go down the computing route, with CFD—computational fluid dynamics—rather than build another wind tunnel. When we built our new compute cluster in 2007, the plan was that we'd double our compute every year. Very quickly it was realised that the teams with huge budgets—the manufacturer-backed teams—would get an unfair advantage over smaller teams, because they didn't have the money to build these enormous clusters."

Soon after, to prevent the larger F1 teams from throwing more and more money at aerodynamics, the FIA began restricting both wind tunnel usage and compute power for simulations.

reader comments

74