FRITILLARIA

by Subhuti Dharmananda, Ph.D., Director, Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon

Fritillaria refers to the bulb (corm) of Fritillaria cirrhosa (see Figure 1) or Fritillaria thunbergii (see Figure 2) of the Lily Family (Lilaceae). The Chinese name, beimu, refers to the appearance of the bulb being similar to that of the cowry shell (bei) of which the plant is the source (mu = mother).

Fritillaria cirrhosa, known as chuanbeimu (chuan = from Sichuan Province) has a very small corm which is considered superior, in terms of medicinal benefits, to that from Fritillaria thunbergii (zhebeimu; mainly from Zhejiang Province) which has a larger corm (see Figure 3). Due to the difficulty and high cost of collecting a large number of plants to get an adequate quantity of small bulbs for Fritillaria cirrhosa, Fritillaria thunbergii has become extensively utilized as a substitute, though it is said to have slightly different applications (see Appendix). Today, virtually all supplies of fritillaria are cultivated; limited collection of wild chuanbeimu still takes place in Tibet and Yunnan.

Although fritillaria is mentioned in the ancient literature, including a brief statement in the Shennong Bencao Jing (1) and inclusion as a secondary ingredient in one formula of the Shanghan Lun (2), it was not widely used in ancient medicine. This lack of use probably reflects the difficulty in finding adequate quantities of the herb. zhebeimu was first introduced formally in the Bencao Gangmu (1578 A.D.); this larger bulb plant, and introduction of cultivation as a major commercial venture during the Ming Dynasty, paved the way for the herb to be utilized regularly thereafter.

According to traditional descriptions that are found in the later texts, fritillaria is slightly cold, and affects the lungs (to clear heat and moisten dryness, used for hot-type bronchitis with dry cough) and the heart (to calm heart fire). Fritillaria is also used for treating lumps beneath the skin, such as scrofulous swellings and breast lumps. Zhebeimu is often used for the treatment of lumps (the moistening property attributed to chuanbeimu is not needed); it has been adopted into some Chinese herb formulas for treating cancers.

An early proponent of using fritillaria in phlegm-resolving formulas was Gong Tingxian (for more information about this physician, his theories, and formulations, see: Chinese herbs for lymphedema). He wrote Wanbing Huichun (1587 A.D.), which presented many of his prescriptions; among his fritillaria-containing formulas that are still used today, particularly in Japan and Taiwan (3), are Qingfei Tang (Platycodon and Fritillaria Combination) and Gualou Zhishi Tang (Trichosanthes and Chih-shih Combination).

In most of the traditional prescriptions, fritillaria is a minor component of a large formula (4). Even in Beimu Tang (Fritillaria Decoction), there are a dozen ingredients and fritillaria makes up just 10% of the formula by weight. However, there are a few formulas of 6-8 ingredients in which fritillaria is a significant component. Its largest contribution among formulas published in modern guides is in Beimu Gualou San (Fritillaria and Trichosanthes Powder) and Beimu San (Fritillaria Powder); both formulas have only six ingredients, with fritillaria making up 28% and 22% of the formula, respectively. It is also an ingredient of the Anemarrhena and Fritillaria Pill for Stopping Cough (Ermu Ningsou Wan; ermu = two mu, referring to anemarrhena, zhimu, and fritillaria, beimu; ningsou = stop cough), a formula of 11 ingredients that includes trichosanthes, an herb frequently combined with fritillaria in the traditional formulas for lung disorders.

Today, fritillaria is commonly included as a main ingredient in manufactured cough syrups (zhike lu: zhike = treating cough; lu = syrup); another major ingredient in most of the syrups is pipaye, the eriobotrya leaf, commonly called loquat. Among the formulas on the market are (5): Zhike Chuanbei Pipa Lu (Fritillaria and Eriobotrya Cough Syrup); Luohanguo Zhike Lu (Momorida Cough Syrup); Milian Chuanbei Pipa Gao (Refined Honey Fritillaria and Eriobotrya Syrup; gao = thick syrup); and Sanshedan Chuanbei Ye (Three Snake Gallbladder and Fritillaria Liquid; ye = a thin syrup).

A well-known food therapy for cough is to steam a sliced pear, in which fritillaria (chuanbeimu) powder and sugar fills the emptied core area. The pear-fritillaria preparation is then eaten (the juice that is formed during cooking is also consumed), one pear per day. A more complex preparation is described in Chinese Medicated Diet (6), in which the pear is prepared with fritillaria, lily bulb, and water chestnut, using the same method of steaming

ACTIVE CONSTITUENTS

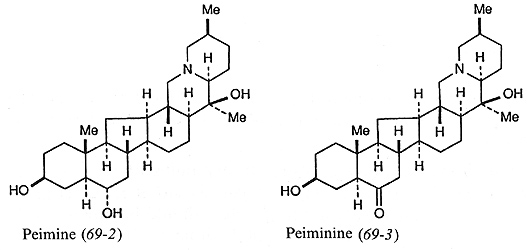

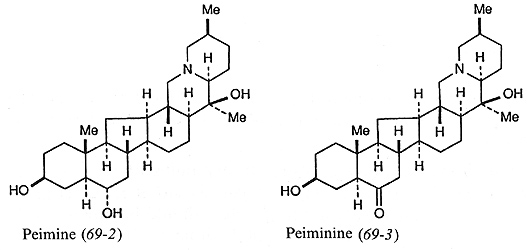

The main active constituents in fritillaria are alkaloids. There are at least eight steroidal alkaloids (such as peimine and peiminine; see Figure 4), and more than 20 other alkaloids, mainly fritimine. The alkaloid content is relatively low, at 0.1-0.4% of the dry weight (7). Some of the alkaloids have been isolated and used for pharmacology testing, revealing antitussive effects, smooth muscle relaxation, and reduction of blood pressure. There are also diterpenes in the bulb, and these may have antitussive effects as well.

DOSAGE

The usual recommended dosage of fritillaria is 3-9 grams in decoction; but doses of 9-15 grams have been suggested (8). In clinical testing, a tablet made of fritillaria powder was taken at a dosage of 2 grams each time, three times daily for treatment of bronchitis. The alkaloid content of the highest recommended dose of 15 grams of fritillaria would be 15-60 mg, assuming complete alkaloid extraction in making a decoction.

TOXICITY AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

In China, fritillaria is known as a safe herb that can be used in food preparations (such as fritillaria-pear) and for which there are no expected adverse reactions. Tests of the herb extract administered orally have not revealed any toxic effects. Isolated fritillaria alkaloids administered in high dosage by intravenous administration produce respiratory inhibition, pupil dilation, tremor, blood pressure and heart rate decrease. Acute toxicity testing of intravenous injections indicate that the toxic dosage of the isolated alkaloids in laboratory animals is high, about 10 mg/kg for peimine; the related alkaloid peiminine was 20-30 times less potent than atropine in causing inhibition of mucosal and salivary secretion (9).

OTHER LILACEAE HERBS

Fritillaria is one of several herbs of the Lilaceae that are used in Chinese medicine with similar applications. Table 1 provides an overview of six of the most commonly used of the Lily family herbs, illustrating the nearly identical applications for clearing heat, moistening dryness, and alleviating coughing (8).

Table 1: Lily family herbs in Chinese medicine used for cough and bronchitis.

|

Herb Names

|

Botanical name, Part Used

|

Traditional Description of Actions/Uses

|

|

Anemarrhena

zhimu

|

Anemarrhena asphodeloides

immature branch root

|

clears heat, moistens

dryness; treats cough associated with fatigue

|

|

Asparagus

tianmendong

|

Asparagus lucidus

tuber

|

nourishes yin, clears

heat, moistens dryness, controls cough; used for dry cough of consumptive

disease

|

|

Fritillaria

beimu

|

Fritillaria cirrhosa/thunburgii

bulb

|

moistens dryness to

resolve phlegm, controls cough, clears heat

|

|

Lily

baihe

|

Lilium brownii

bulb

|

nourishes yin,

moistens lungs, controls cough; used for cough associated with weakness and

hemoptysis

|

|

Ophiopogon

maimendong

|

Ophiopogon japonicus

bulb

|

nourishes yin,

moistens dryness, clears heat, controls cough

|

|

Yu-chu

yuzhu

|

Polygonatum officinale

rhizome

|

nourishes yin, moistens

lungs; used for dry cough due to lung heat

|

The traditional formula Zhisou Baihua Wan (Lily and Trichosanthes Pill for Stopping Cough) is a large prescription of 18 herbs that includes virtually all the Lily family herbs for controlling cough: anemarrhena, asparagus, lily, fritillaria, and ophiopogon. The formula ingredients are ground to powder, made into large honey pills (10 grams, of which about one-third is honey), and taken one pill each time with warm water. It is indicated for lung heat syndromes with symptoms such as coughing, hemoptysis, and accompanying spontaneous sweating and fever. A food therapy for cough, based on Lily family plants, is described in Chinese Medicated Diet; the preparation is Bai Yu Erdong Zhou, which is a gruel made with lily, yu-chu, asparagus, and ophiopogon. The herbs are first cooked as a decoction and then that liquid is used to cook rice; honey is added as a flavor to counter bitterness, and also to help treat the cough. The gruel is indicated for chronic bronchitis with yin deficiency.

REFERENCES

- Yang Shou-zhong (translator), The Divine Farmer's Materia Medica, 1998 Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO.

- Hsu HY and Peacher WG (translators) Shang Han Lun, 1981 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

- Hong-Yen Hsu and Chau-Shin Hsu, Commonly Used Chinese Herb Formulas with Illustrations, 1980 rev. ed., Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

- Huang Bingshan and Wang Yuxia, Thousand Formulas and Thousand Herbs of Traditional Chinese Medicine, vol. 2, 1993 Heilongjiang Education Press, Harbin.

- Fratkin J, Chinese Herbal Patent Formulas: A Practical Guide, 1986 Shya Publications, Santa Fe, NM.

- Zhang Enquin (ed. in chief), Chinese Medicated Diet, 1988 Publishing House of Shanghai College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai.

- Yen Kunying, Illustrated Chinese Materia Medica, 1992 SMC Publishing Inc., Taipei, Taiwan.

- Hong-Yen Hsu, et al., Oriental Materia Medica: A Concise Guide, 1986 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

- Hson-Mou Chang and Paul Pui-Hay But (eds.), Pharmacology and Applications of Chinese Materia Medica, (2 vols.), 1986 World Scientific, Singapore.

- Dong Zhiling and Yu Shufang, Modern Study and Application of Materia Medica, 1990 China Ocean Press, Hong Kong.

- Cheung CS and Kaw UA, Synopsis of the Pharmacopoeia, 1984 American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, San Francisco, CA.

- Bensky D and Gamble A, Chinese Herbal Medicine Materia Medica, 1993 Eastland Press, Seattle, WA.

- State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology, (vol. 2) 1995-6 New World Press, Beijing.

APPENDIX: Commentaries on Distinguishing chuanbeimu and Zhibeimu

While some authorities view chuanbeimu and zhebeimu as interchangeable, having only slight differences, others consider them to have significantly different characteristics that should be given attention when designing an herb formula. Following are some examples of the presentations about the two herbs. It will be seen that it is sometimes difficult to discern the areas of agreement among the sources, which can lead to confusion and differing opinions by practitioners who are influenced by different sources. However, there are basic trends in the descriptions that can lead to a consensus statement.

Oriental Materia Medica (8):

- chuanbeimu is effective for treating tuberculosis and hemoptysis;

- zhebeimu is good for cough due to external pernicious influence, incised wound toxin, carbuncle, scrofula, toxic swelling, and laryngeal ulcer.

Thousand Formulas and Thousand Herbs of Traditional Chinese Medicine (4): In this text, the functions of both types of beimu are: 1. To resolve phlegm and stop cough; 2. To clear heat and disperse lump. For dispersing lumps, both are said to have the following indications: scrofula, sores and carbuncles, lung carbuncles, and acute mastitis. In relation to cough, the indications differ slightly.

- chuanbeimu: chronic cough with scanty sputum and dry throat due to deficiency of lung; cough due to wind-heat; cough with yellow and thick sputum due to stagnation of phlegm and fire, especially chronic cough and dry cough.

- zhebeimu: used chiefly for cough due to wind-heat or stagnation of phlegm and fire.

Modern Study and Application of Materia Medica (10):

- chuanbeimu: Property and Flavor: neutral in property, mild in potency, sweet and bitter. Actions: to moisten the lungs and resolve phlegm, clear away heat and disperse accumulation of pathogen. Indications: cough with no expectoration due to excessive heat in the lungs; cough due to deficiency of the lungs, and cough due to phlegm-heat; inflammation of the throat, dizziness, consumptive lung diseases, and galactostasis.

- zhebeimu: Property and Flavor: cold and bitter. Actions: to relieve cough and reduce sputum, clear away heat and disperse accumulation of pathogen. Indications: persistent cough due to deficiency of the lungs or cough caused by invasion of exogenous wind and heat; scrofula, carbuncles and boils, pulmonary abscess, acute mastitis, and dry throat with little phlegm.

Synopsis of Pharmacopoeia (11):

- chuanbeimu lubricates the lung, disperses entanglement, relieves cough, and dissolves sputum. It is indicated for deficiency/exhaustion cough, excessive sputum, congestion/entanglement of chest, lung abscess, thyroid tumors, swollen abscess and is applied externally for evil ulcers.

- Zhibeimu clears heat, dissipates entanglement, lubricates lung and dissolves sputum. It is indicated for phlegm-heat cough, lung abscess, numb painful throat, lymph node enlargement, ulcers, and toxic swellings.

Chinese Herbal Medicine Materia Medica (12): As with other texts, the indication of clearing heat and dissipating nodules is almost identical for the two varieties of beimu; however, the descriptions of use for treating lung diseases differ:

- chuanbeimu: clears heat and transforms phlegm: for many types of cough, chiefly chronic cough, cough with signs of fire due to yin deficiency, cough with slight sputum that is difficult to expectorate, or cough with blood-streaked sputum. It is most effective in treating cough accompanied by constrained qi, manifested in a reduced appetite and stifling sensation in the chest and upper abdomen.

- zhebeimu: clears and transforms phlegm-heat; for acute lung heat patterns with productive cough.

In sum, chuanbeimu may be said to be more tonifying and moistening (that is, it especially nourishes the yin), having a sweet taste (indicating tonic properties), and being suitable for patients with evident weakness (deficiency syndrome) and for those with chronic disease involving cough. zhebeimu may be said to lack significant tonic properties (having no sweet taste, only the bitter taste) and be more suited to treatment of acute lung diseases (even though one text indicates it for "persistent cough due to deficiency of the lungs"). Both herbs are equally suited to treating swellings. The Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology (13) offers this appropriate summary:

Both chuanbeimu and zhebeimu can purge heat and resolve heat-phlegm. The former is sweet, bitter, and slightly cold, and has a stronger action of moistening the lung, and is indicated for cough due to heat and dryness in the lung and prolonged cough due to yin deficiency. The latter is bitter and cold, and is better at purging heat and toxins.

March 2001

Figure 1: Fritillaria cirrhosa.

Figure 2: Fritillaria thunbergii.

Figure 3: The corms of Fritillaria cirrhosa (left) and Fritillaria thunbergii (right).

Figure 4: Two of the main alkaloids of fritillaria: peimine and peiminine.